This document summarizes good agronomic practices (GAP) that can be used to manage diseases in faba bean crops. It discusses how crop diversification, intercropping faba beans with cereals, and appropriate crop rotations can disrupt disease cycles and reduce pathogen buildup. Intercropping in particular has been shown to decrease incidence and severity of diseases in both faba beans and intercropped components. The document also reviews how faba beans can improve soil nitrogen levels and increase yields and protein content of subsequent crops. Finally, it provides an overview of the most important diseases of faba beans, including chocolate spot, ascochyta blight, and rust, and how GAPs like rotations, tillage, and

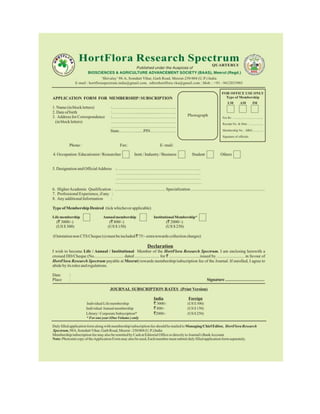

![Distribution pattern of diamondback moth on cabbage under gangetic alluvial condition 147

,htomkcabdnomaidfonrettapnoitubirtsiD:1elbaT,alletsolyx.P5gnirudegabbacylraenoht

9ot9002,rebotcOht

.9002,rebmevoN

foetaD

gnikat

noitavresbo

porC

ega

)syaD(

fo.oN

selpmas

naeM

X

ecnairaV

S2

noisrepsiD

retemaraP

K

X

Sx

=

-

2

2

foxednI

-repsiD

nois

IdS=2

/`X

lacorpiceR

)K/I(=Kfo

-ixaM

mum

-lugeR

ytira

)n/1(

s’eloC

xednI

IC=

Sx2

(/Sx)2

reilrahC

tneiciffeoC

001´

SX2

-

´/1X

dyolL

foxedni

naem

gnidworc

=xx+

s([2

/x])-1

dyolL

ssenihctap

xedni

90/01/505104574.0178.0075.0438.1657.1520.0911.0705.231903.1657.2

90/01/010204578.0489.0620.7521.1241.0520.0650.0727.73000.1241.1

90/01/515204053.1009.2671.1841.2058.0520.0460.0122.29894.2058.1

90/01/020304058.1779.3906.1051.2126.0520.0350.0238.87000.3126.1

90/01/525304057.1639.3104.1942.2417.0520.0650.0484.48999.2417.1

90/01/030404005.1333.3722.1222.2518.0520.0160.0762.09227.2518.1

90/11/405404524.1016.2417.1138.1385.0520.0650.0973.67652.2385.1

90/11/900504009.0624.1145.1485.1946.0520.0860.0755.08484.1946.1

,htomkcabdnomaidfonrettapnoitubirtsiD:2elbaTalletsolyx.P32gnirudegabbacno,dr

81ot9002,rebmevoNht

no(9002,rebmeceD

)egabbacnosaes

foetaD

gnikat

noitavresbo

porC

ega

)syaD(

fooN

selpmas

naeM

`X

ecnairaV

S2

-repsiD

nois

retemaraP

K

X

Sx

=

-

2

2

foxednI

-repsiD

nois

IdS=2

/`X

lacorpiceR

fo

)K/I(=K

mumixaM

ytiralugeR

)n/1(

s’eloC

xednI

IC=

Sx2

(/Sx)2

reilrahC

eiciffeoC

tn

001´

SX2

-

´/1X

dyolL

foxedni

naem

gnidworc

=xx+

s([2

/x])-1

dyolL

ssenihctap

xedni

90/11/325104524.0217.0926.0676.1095.1520.01121.0290.621101.1095.2

90/11/820204528.0969.0047.4471.1112.0520.07950.0139.54999.0112.1

90/21/305204520.1652.1355.4522.1022.0520.01450.0768.64052.1022.1

90/21/800304057.0019.0015.3412.1582.0520.04460.0673.35469.0582.1

90/21/315304006.0957.0562.2562.1244.0520.04670.0354.66568.0244.1

90/21/810404523.0536.0043.0559.1739.2520.06171.0783.171082.1739.3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fc9a88a7-3f12-4a93-90ce-e99b05cd72f3-161102170131/85/6-HortFlora-Full-PDF-Vol-2-2-Apr-Jun2013-59-320.jpg)

![148 Goswami and Mukhopadhyay

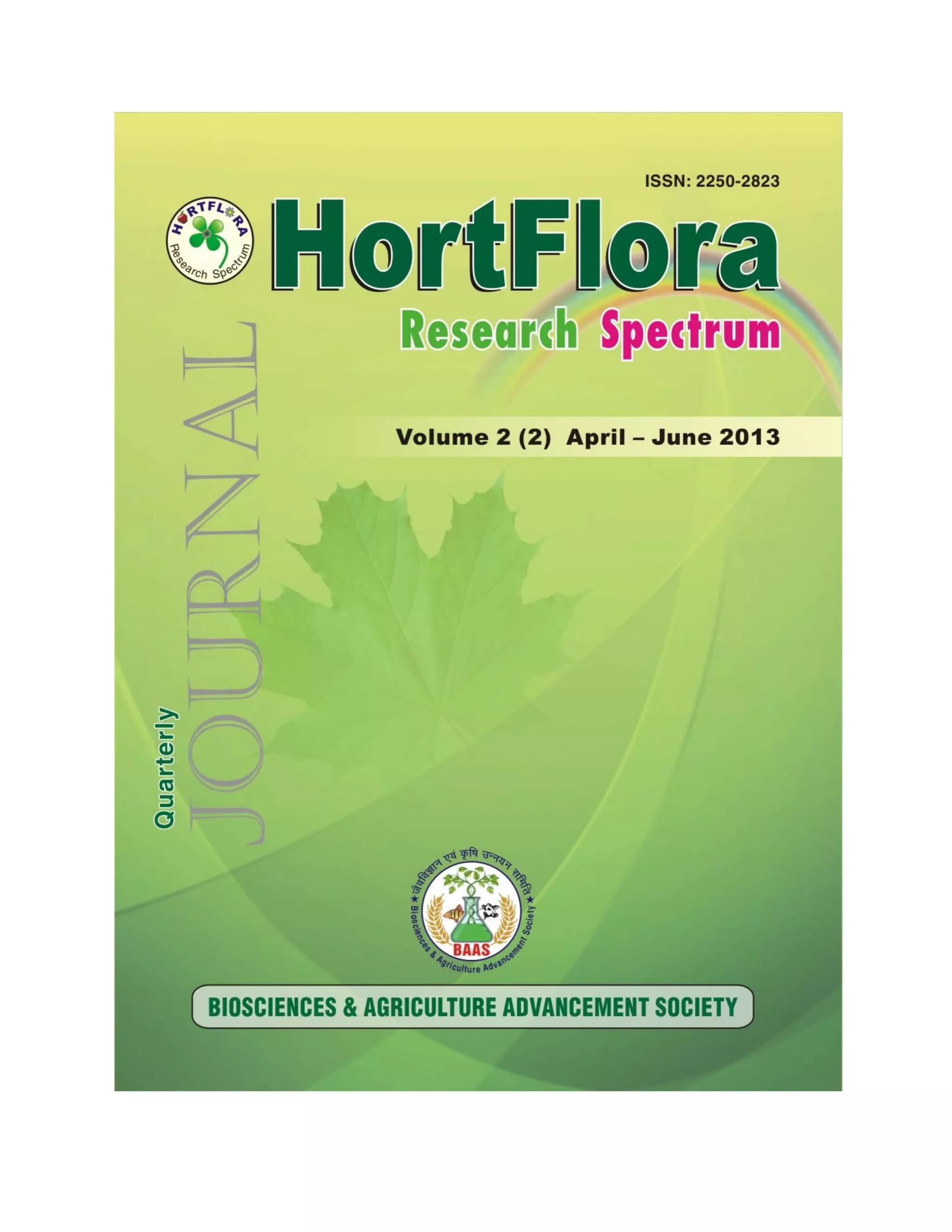

moth was aggregative distribution. The study

further indicated that aggregation was species

characteristic, as it did not alter even in different

cabbage seasons.

Distribution pattern of diamondback moth on

cabbage have been studied by various scientists in

different parts of India but it is reported by the

present author for the first time from West Bengal.

Rai et al. (7) studied the spatial distribution of

diamondback moth on cabbage and cauliflower at

Panipat (Haryana), Jaunpur (Uttar Pradesh) Ranchi

(Jharkhand) and Delhi during 1988-89 and they

found the aggregative pattern of distribution of the

pest on both the crops which corroborates the

finding by the present author. Reddy et al. (8)

reported spatial distribution of DBM larvae on

cabbage at Hyderabad during 1994-95. They

calculated several indices like variance-mean ratio,

Coles Index, K of negative binomial and Lloyds

Index of mean crowding which showed aggregative

nature of distribution of diamondback moth. The

value of these indices in present study also

supported the same distribution pattern as reported

by Reddy et al. (8) and Mishra et. al. (6). The

findings of the present study also corroborated the

distribution pattern as reported by Koteswara Rao

and Lal (4) who also reported spatial distribution

pattern of DBM larvae on cabbage under Delhi

condition.

REFERENCES

1. Anonymous (2005). Cabbage: Cabbage History,

Cabbage Facts & Recipes. USDA Nutrient

Database. Available from

http://www.nal.usda.gov/2005/fnic/food.

2. Cole, L.C. (1946). A theory for analyzing

contagiously distributed populations. Ecology,

27 : 329-341.

3. Elliott, J.M. (1977). Some methods for

statistical analysis of benthic invertebrates.

Fresh water biological association. Scientific

Publication- 25, P. 156 .

4. Koteswara Rao, S.R. and Lal, O.P. (1999).

Distribution pattern of diamondback moth

,htomkcabdnomaidfonrettapnoitubirtsiD:3elbaTalletsolyx.P82gnirudegabbacetalno,ht

2ot0102,yraurbeFdn

0102,lirpA

foetaD

gnikat

-avresbo

noit

egaporC

)syaD(

fooN

selpmas

naeM

`X

-iraV

ecna

S2

-repsiD

nois

-araP

retem

K

X

Sx

=

-

2

2

foxednI

-repsiD

nois

IdS=2

/`X

-orpiceR

lac

fo

)K/I(=K

mumixaM

-lugeR

ytira

)n/1(

s’eloC

xednI

IC=

Sx2

(/Sx)2

reilrahC

neiciffeoC

t

001´

SX2

-

´/1X

dyolL

foxedni

naem

gnidworc

=xx+

s([2

/x])-1

dyolL

ssenihctap

xedni

01/20/825104051.1328.1569.1585.1905.0520.06850.0043.17537.1905.1

01/30/400204527.1046.3455.1011.2446.0520.08450.0032.08538.2446.1

01/30/905204059.1316.2737.5043.1471.0520.07140.0157.14092.2471.1

01/30/310304577.2046.6299.1393.2205.0520.00640.0948.07861.4205.1

01/30/815304003.3776.01674.1532.3776.0520.09840.0503.28535.5776.1

01/30/320404007.3780.31854.1735.3686.0520.03840.0708.28732.6686.1

01/30/825404057.5442.02182.2125.3834.0520.09930.0902.66172.8834.1

01/40/200504005.4967.61056.1627.3606.0520.02540.0938.77062.7606.1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fc9a88a7-3f12-4a93-90ce-e99b05cd72f3-161102170131/85/6-HortFlora-Full-PDF-Vol-2-2-Apr-Jun2013-60-320.jpg)