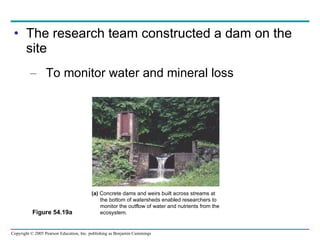

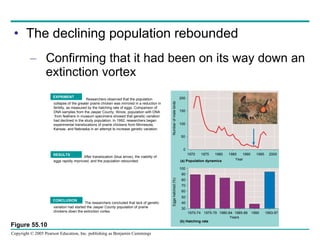

The document provides an overview of community ecology, discussing key concepts such as biological communities, interspecific interactions including competition, predation, herbivory, symbiosis and disease. It describes how species niches allow similar species to coexist, and how dominant and keystone species exert strong controls on community structure through abundance or important ecological roles. Examples are given of studies demonstrating the impacts of species like sea stars and sea otters.