The document discusses the process of selecting an employee benefits package, emphasizing the need for aligning benefits with organizational goals, employee expectations, and budget constraints. It highlights the importance of understanding employee demographics and preferences in determining which benefits to offer, and the potential advantages of flexible or cafeteria-style plans that cater to individual needs. Additionally, it underscores the significance of evaluating benefits annually to assess their impact on employee morale and productivity.

![clental and vision coverage

rhemselr,es because of ii-r. u"l.,e'tl-re1, place on this benefit.li

Enplol,ers shoulcl also consitler thal the valre etlployees place

on various benefits

is likeb, to cliffer frorn one employee ro another. At a broad

let'el, basic ciernographic

iactors sr-ich as age ancl sex cal-1 influence the kinds of

benefits emplo1'ggs want. An

olcler u,orkforce is more 1ikely to be concerned about (antl use)

rnedical col'erage' life

insnrance, and ;rensions. A workforce $'ith a high lrercelltage

of s'omen of childbear'

ilrg :rge tna)/ cafe more abolrt clisabiiity or farnilv leave. Yor-

rug, untnarried men and

r,,Jrr-rJr-, often place more t,alue on p:ry than on benefits'

Hon'ever, these are or-rly

general obseryations; organizatiols sfiould check rvhich

consideratrons apply to their

3r',,,r-r

"roployees

ancl identifi,'rnore specific nee'i]s and .'litfer..ences' One

approach is to

ur. ,.,.u"1,, to usk errployees about t-he kinds of benefits lhel

i'alue. The survey should

be carefpl11' ,orcled so as not to raise emplo;'ss5'

expectatiolls b)- seemir-ig to prornise](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/444part4compensatinghumanresourceslexplainhowto-221112184520-e31475bb/85/444-PART-4-Compensating-Human-ResourcesL-Explain-how-to-docx-9-320.jpg)

![Benefits'Costs

Er,rployers also need to consider benefits cos6. one

place to start is rvith general

i'rformarion about the average costs of rurio*-b"rr"fits

types. fidelv used sources of

cosr dara include th. Br."ui of Labor S,"rit,l.t

igls),'i*pto'ee,Renefit

Research

l.rsrirure, and U.S. Ch;;t., of Cominerce. Annual slrrveys by the

Chamber

of Corn'

nerce stare rhe cost of benefits as a percentage of total

payroll costs and in dollar

tttillolor.rs

can use data about costs to help them t:l"tl :l:,

klnds of benefits to

oifer. But in balancing these decisions against organizational

goals-and employee ben-

efits, the organization -uy d..id" ,o ofl", ..rol]', high-cost

b"r-re{itt while also look-

ing for ways ro .orrrrol-,h. cost of those bene{its. The

highest'cost items tend to offer

rhe mosr room foffur*gr, uri ""rv

if the items permit choice or negotiation. Also,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/444part4compensatinghumanresourceslexplainhowto-221112184520-e31475bb/85/444-PART-4-Compensating-Human-ResourcesL-Explain-how-to-docx-16-320.jpg)

![loo,"i'cost plan. Excluding or limiting

coverage for certain ;;, ;i .l;ims also can slow rhe increase in

health

insurance

costs. Employee wellness programs, especialiy rvhen

they are targeted to employees

*,ith risk factors ur-,a'ir'r.t.,a"-folio*-.,p and encouragement'

can reduce risk factors

tbr disease.3T

Legal R*quirernents fcr Empl*yee Benefits

As we discussed earlier in this chapter, some benefits are

required

by law' This

;.;,,1.-"j;;;"aa, ," t6e cost of to*pe''suting employees'

organizations

iooking for

;;;;.o't*ol ,tuffi,'tg.o"' 'ouy

iook fo'i"uyt'o structLlre tnt l:::|t:lt^t^t"tr3:

to mininize the expense of benefits. They nay require

o'e{time' Iather tt]an aoo-

;;g;;;

"*ploy""r,'hi."-part-time

rath.er rhan full'ti*-ie q'orkers (because parl-tirrle

employees generally .;i;; ;".h smaller benefits packages), and](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/444part4compensatinghumanresourceslexplainhowto-221112184520-e31475bb/85/444-PART-4-Compensating-Human-ResourcesL-Explain-how-to-docx-18-320.jpg)

![.., ah" authority, training, and resources they need. Under these

conditions, employ-

ees will likely conclude that the merit pa] syslsrn is unfair'

Qualiry guru'$U. Edwards Deming also criticizes merit pay

for discouraging team-

*o.i. Ir-, b.-ing's words, "Everyone propeis himself forward, or

tries to, for his own

good, on hi, orin life preserver. ffr. organization is the

1oser."15 For exarnple, if

E*pioy..r in the purch"ri.rg d.purt-ent afe evaluated based on

the number or cost of

.o.rrru.,, they negotiate, they may have little interest in the

quality of the materials

they buy, ..r.r, *f,.r, the manufacturing department is having

quality problems' In

."u.rlor-r'to such problems, Deining advocated rhe use of group

incentives' Another

alternative is for merit pay to include ratings of teamwork and

cooperation' Some

ernployers ask co-workers to provide such ratings'

Performance Bonuses

Like merit pay, performance bonuses reward individual

performance, but bonuses are

not roiled into tase pay. The employee must fe-earn rhem during

each performance

period. In some .ur"i, ,h. bo.r'ls is a one-titne reward. Bonuses](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/444part4compensatinghumanresourceslexplainhowto-221112184520-e31475bb/85/444-PART-4-Compensating-Human-ResourcesL-Explain-how-to-docx-22-320.jpg)

![$8^p:t hour, it can

pay

"

p]"."*".f. ."i" of $B/hour dividea by 10 -components/hour,

o. $.80 per component'

A"-,

"rr.*bl"r

who produces the average of 10 components per hour earns an

amount

e.,rral ro $8 oer tro.r., i., assernbler *Lo prod.',.es 12

components in an hour would

;il^$.80;":.2, o, g9.60 each hour. Thii is an example of a

straight piecework

pl"i, U..""r. th" .*ployer pays the same rate per piece' no matter

how much the

r.vorker produces.

Piecework Rate

A wage based on

the amount workers

produ ce.

Straight Piecework

Plan

lncentive pay in which

the employer PaYS the

same rate Per Piece,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/444part4compensatinghumanresourceslexplainhowto-221112184520-e31475bb/85/444-PART-4-Compensating-Human-ResourcesL-Explain-how-to-docx-39-320.jpg)

![no matter how much

the worker Produces.

i

f

{

n

ti

itllr

!1'Ol

l]ror

ear

:no

Ir

l]tor(

iales

rmpl

if the

:ates

have

This

:har

iiecg,

;erfor

-'atisfa

:ealize

ri hile

lonus](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/444part4compensatinghumanresourceslexplainhowto-221112184520-e31475bb/85/444-PART-4-Compensating-Human-ResourcesL-Explain-how-to-docx-40-320.jpg)

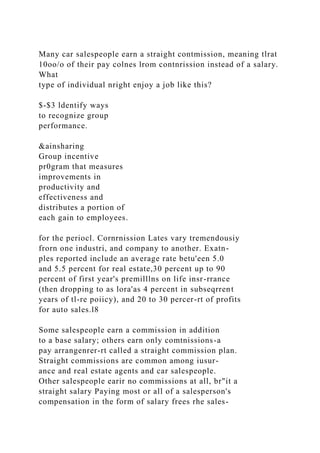

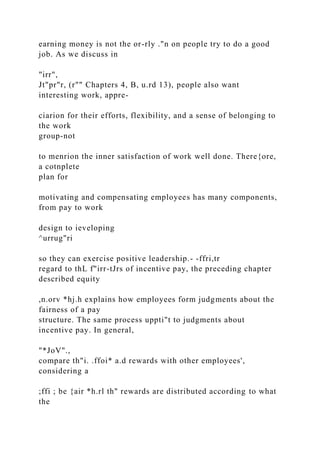

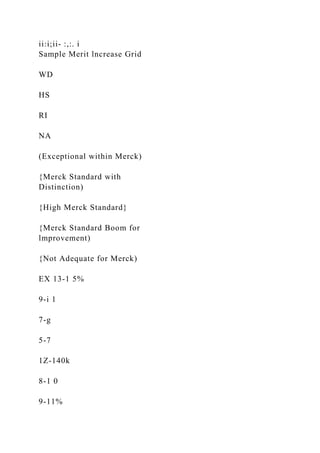

![content and ,"rse of performance appraisals.) To make the merit

increases consistent, so

they r.vill be seen as fair, many merit pay programs use a merit

ina"ease grid, such as the

sample for Merck, the giant drug company, in Table 12.1. As

the table sholvs, the deci'

sioni about merit pay are based on two factors: the individual's

performance rating and

the individual's compa-ratio (pay relative to average pay, as

defined in Chapter 11)-

This s],stern gives the biggest pay increases to the best

performers and to those whose

pay ls relatively lou, for their job. At the highest extreme, an

exceptional employee

earning B0 percent of the average pay for his lob could receive

a 15 percent merit raise.

An employee rated as having "room for improvement" wor,rld

receive a raise only if

that employee was earning relatively low pay for the job

(compa'ratio of .95 or less).

By today's standards, all of these raises are large, because they

were created at a time

wher-r inflation rvas strong and economic forces demanded big

pay increases to keep

up r.vith the cost of living. The range of percentages for a

policy used today would be

iower. Organizations establish and revise merit increase grids in

light of changing eco-

nornic conditions. When organizations revtse pay fanges,

employees have nerv compa-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/444part4compensatinghumanresourceslexplainhowto-221112184520-e31475bb/85/444-PART-4-Compensating-Human-ResourcesL-Explain-how-to-docx-49-320.jpg)

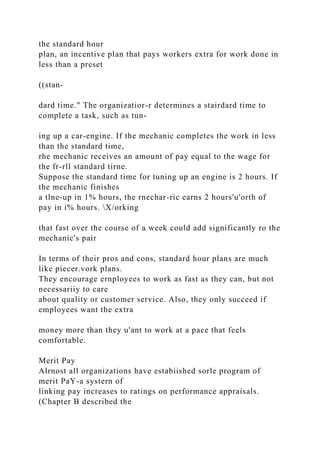

![se.

if

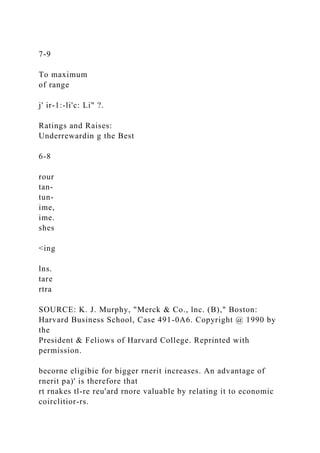

Average Pay lncrease

Highest-Rated Workers

Next Highest Rated

Middle Rated

Low Rated

Lowest Rated

Note: Experts arlvise thaI the top category shou]d receive trsice

as nuch as the ntiddle caleltorv.

).

ne

-^p

be

o-

a-

Io

di.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/444part4compensatinghumanresourceslexplainhowto-221112184520-e31475bb/85/444-PART-4-Compensating-Human-ResourcesL-Explain-how-to-docx-55-320.jpg)