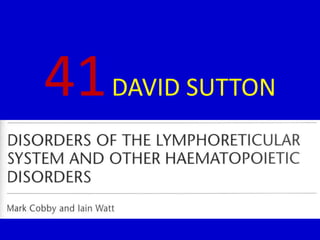

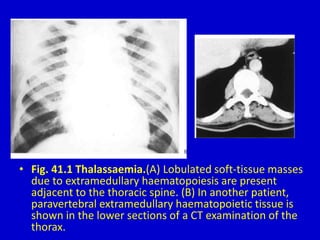

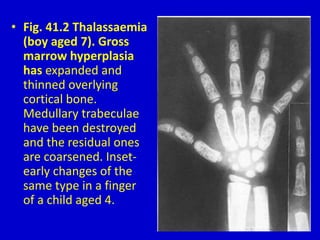

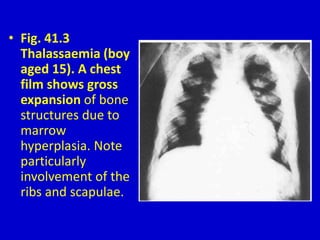

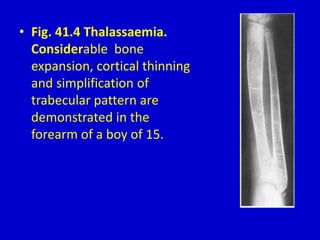

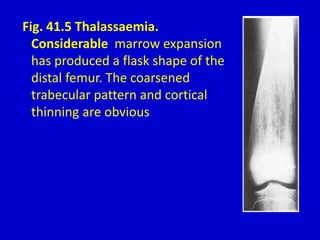

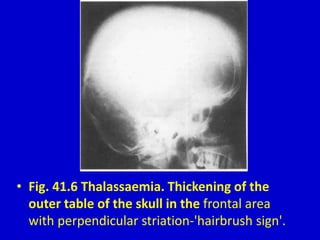

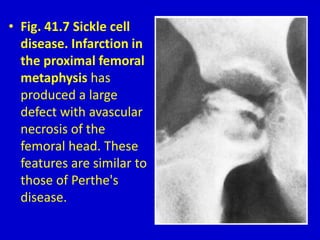

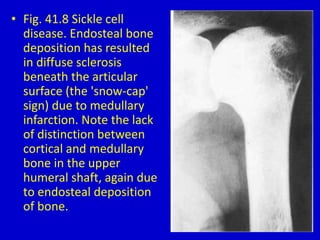

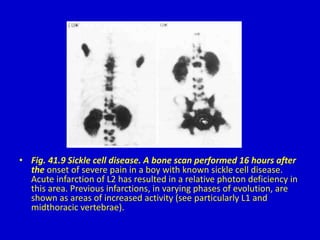

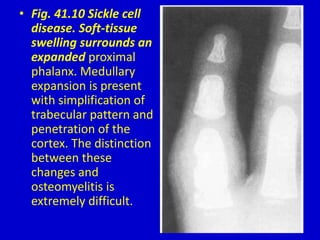

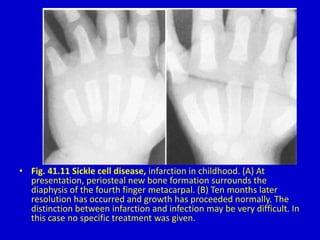

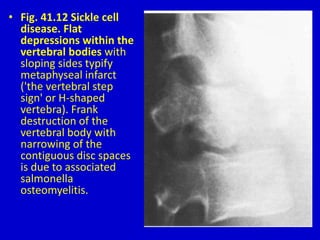

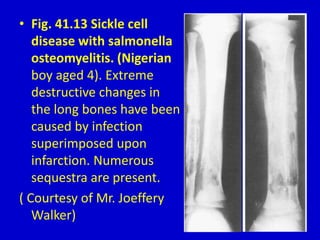

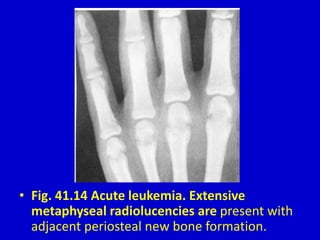

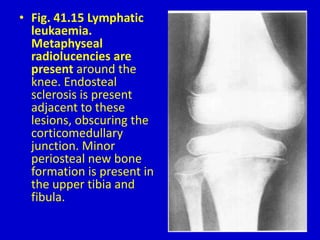

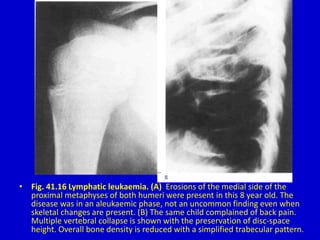

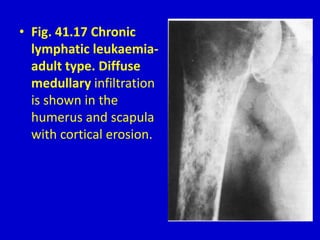

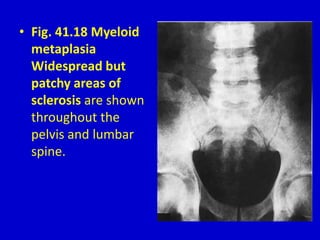

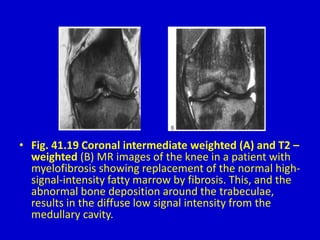

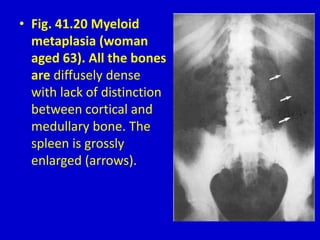

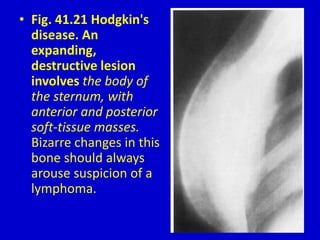

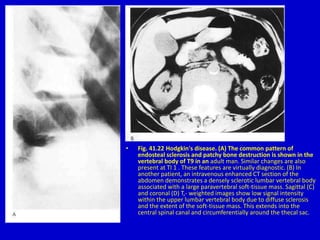

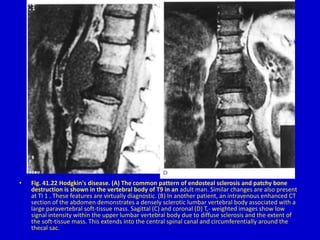

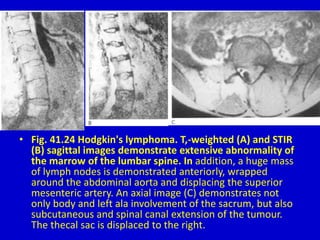

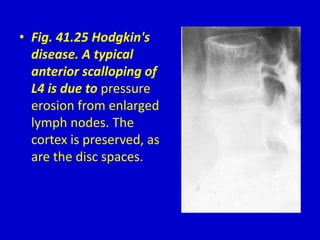

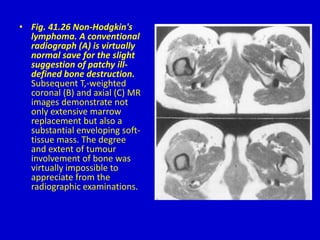

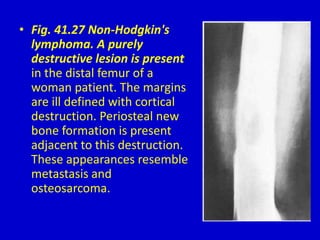

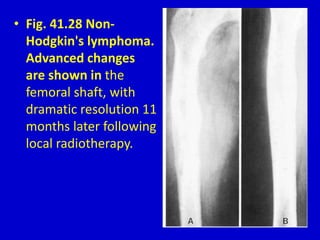

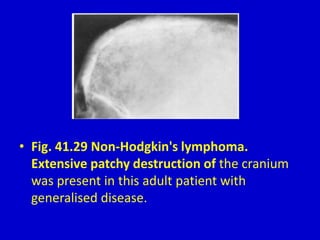

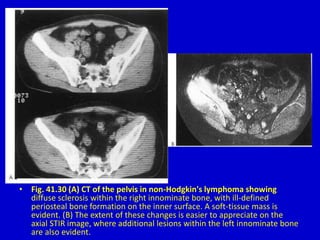

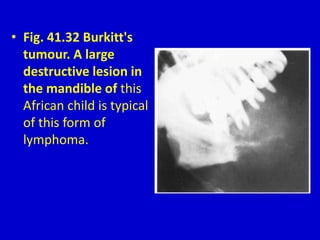

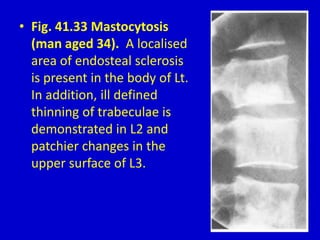

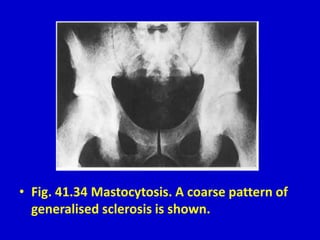

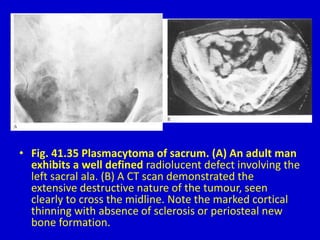

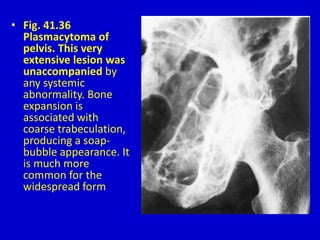

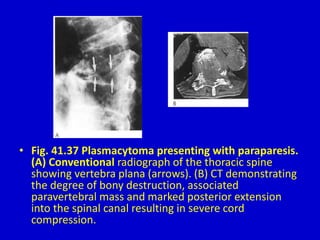

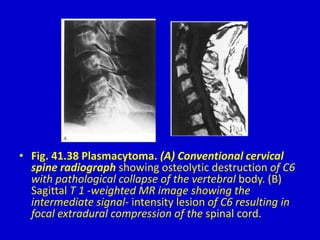

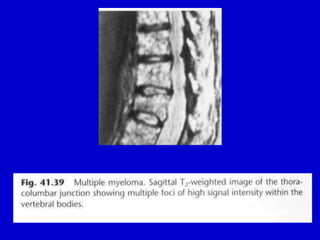

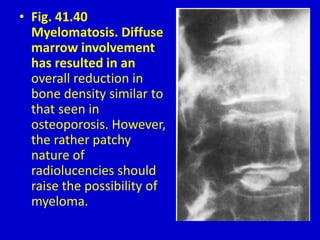

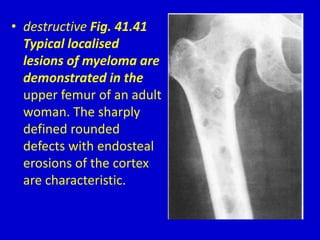

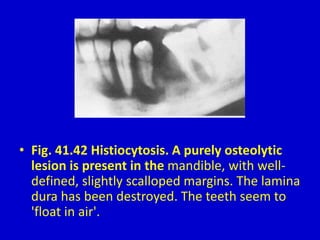

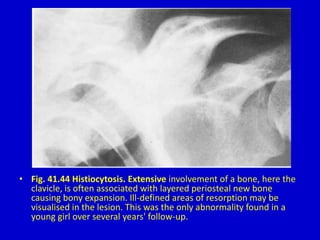

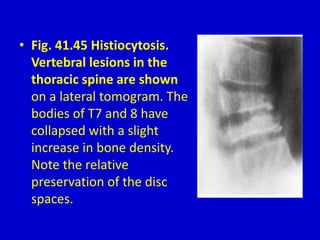

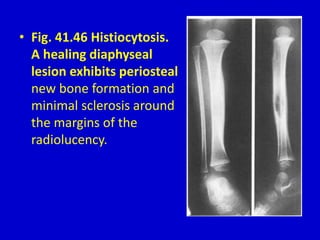

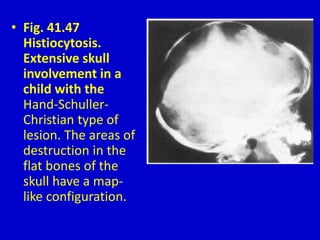

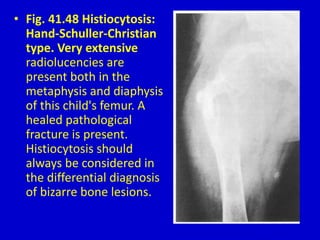

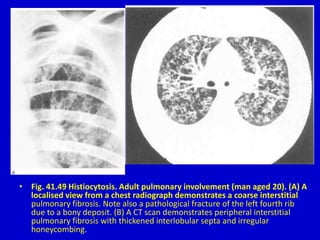

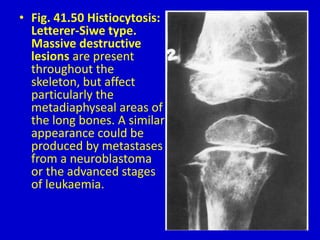

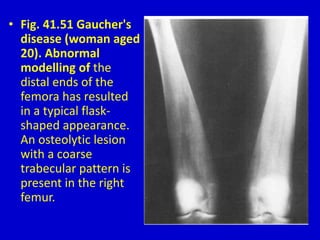

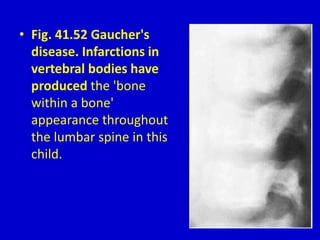

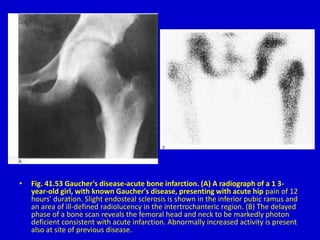

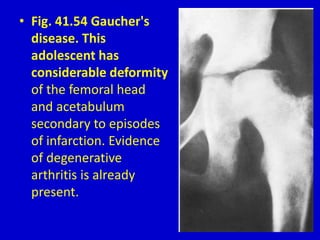

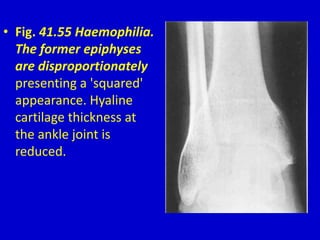

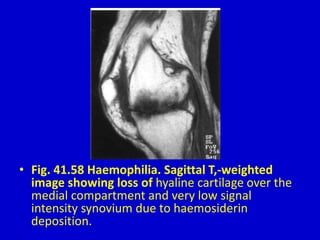

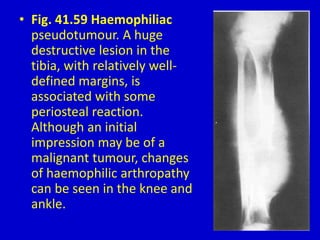

The document discusses various bone pathologies associated with blood disorders, including thalassemia, sickle cell disease, leukemia, and histiocytosis, highlighting characteristic skeletal changes and imaging findings. Detailed descriptions of radiographic and CT appearances related to each condition are provided, indicating how these pathologies manifest in bone structure and density. The document serves as a visual guide for medical professionals to aid in the diagnosis of these hematological diseases through imaging techniques.