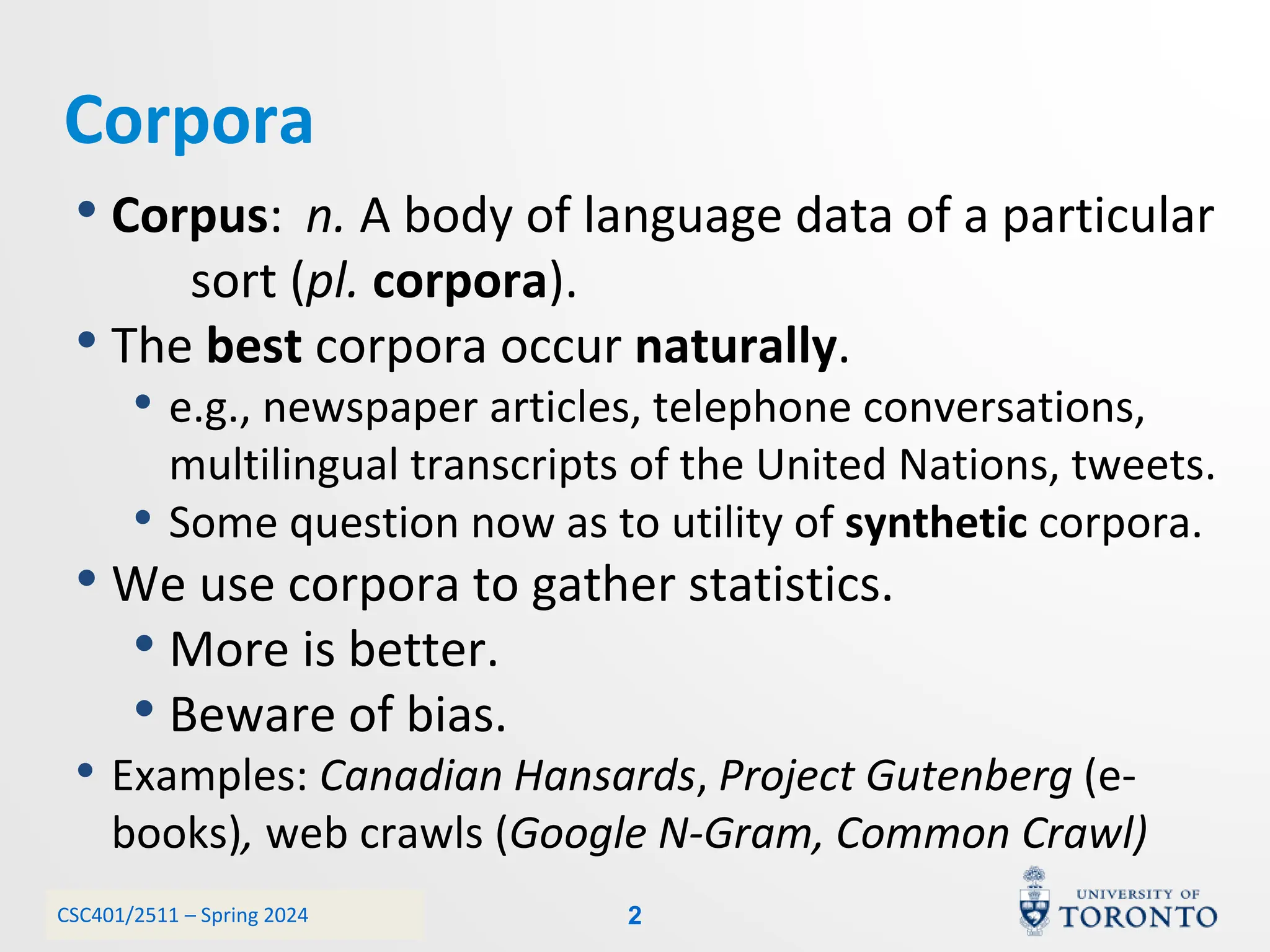

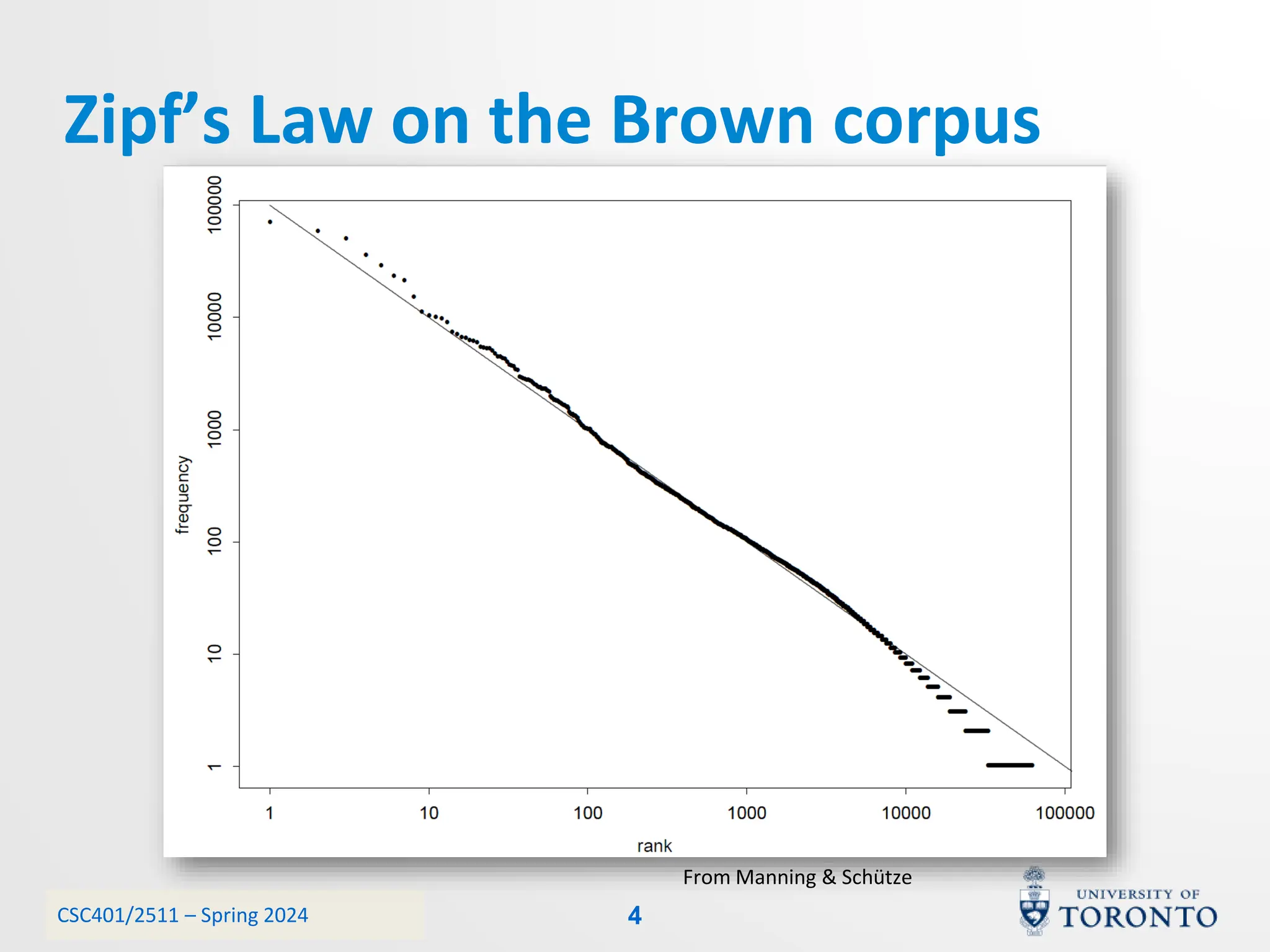

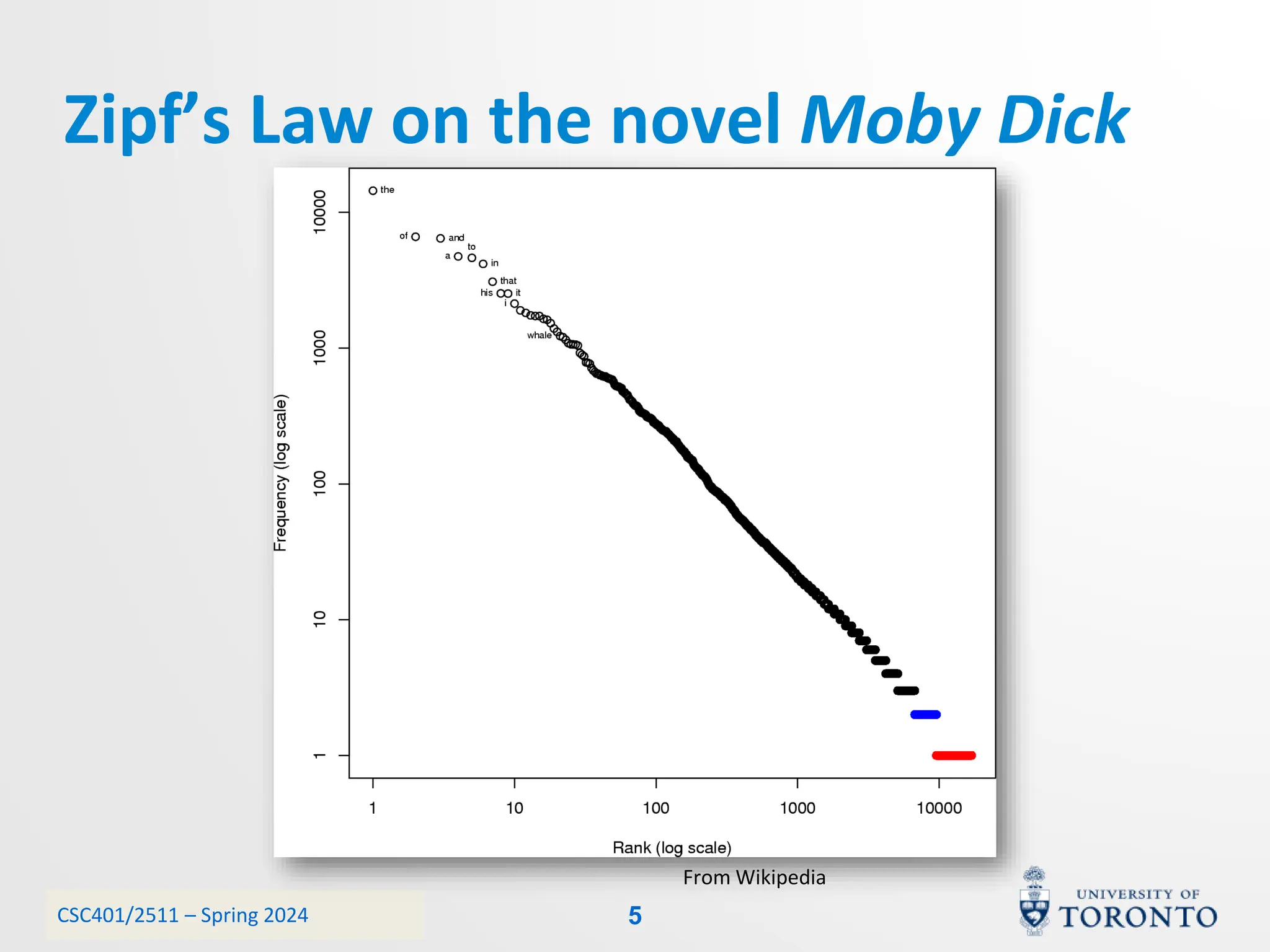

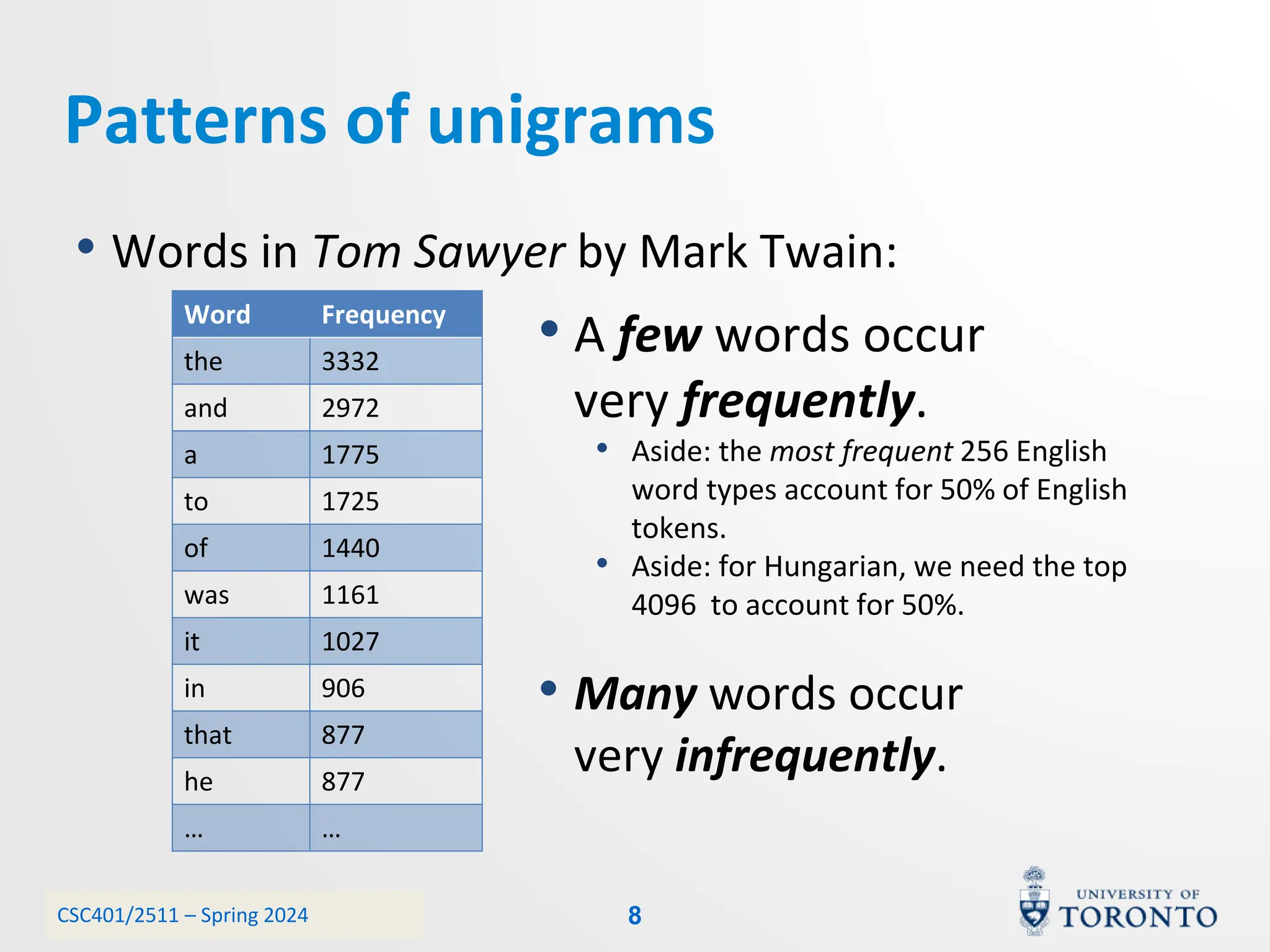

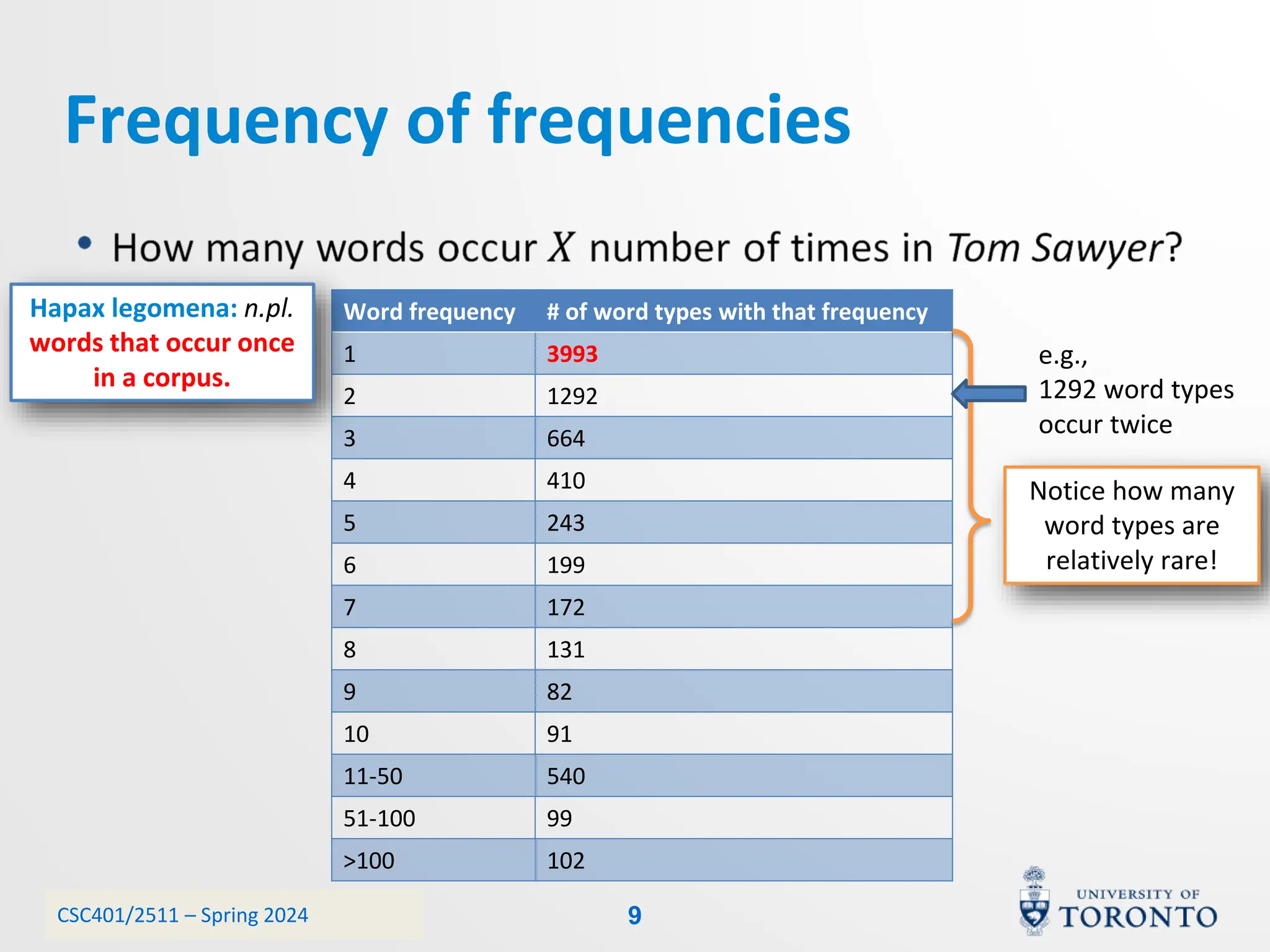

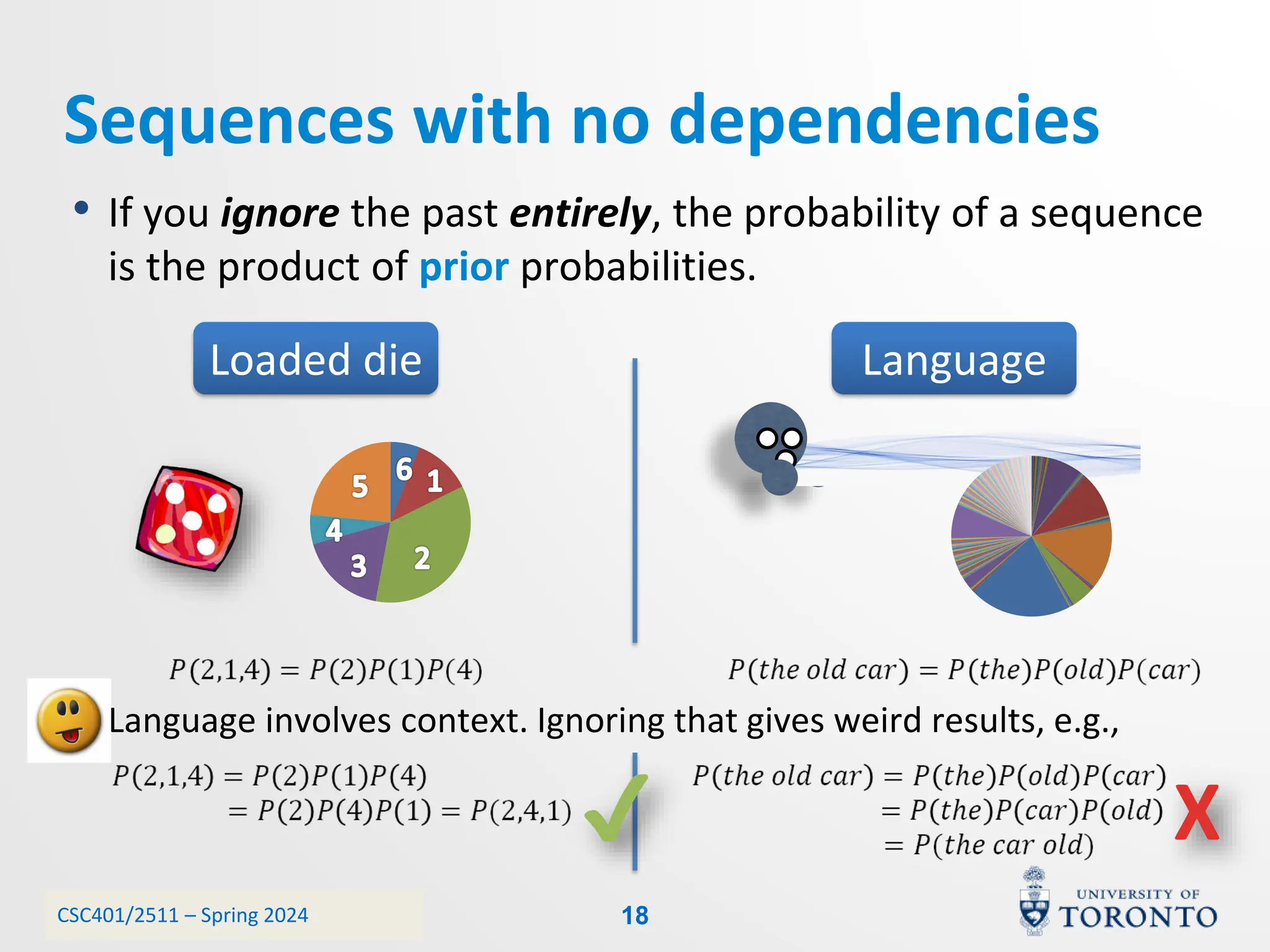

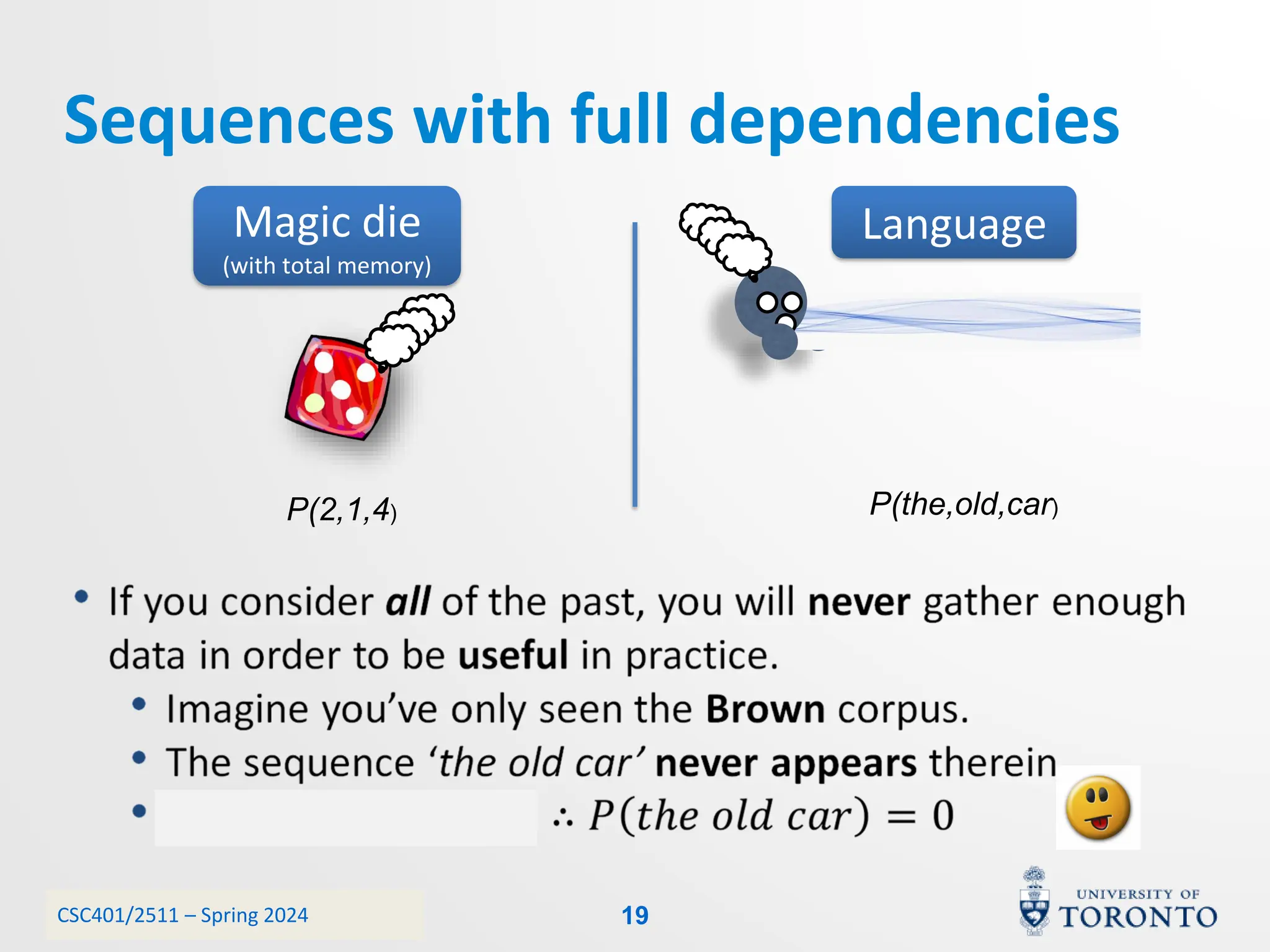

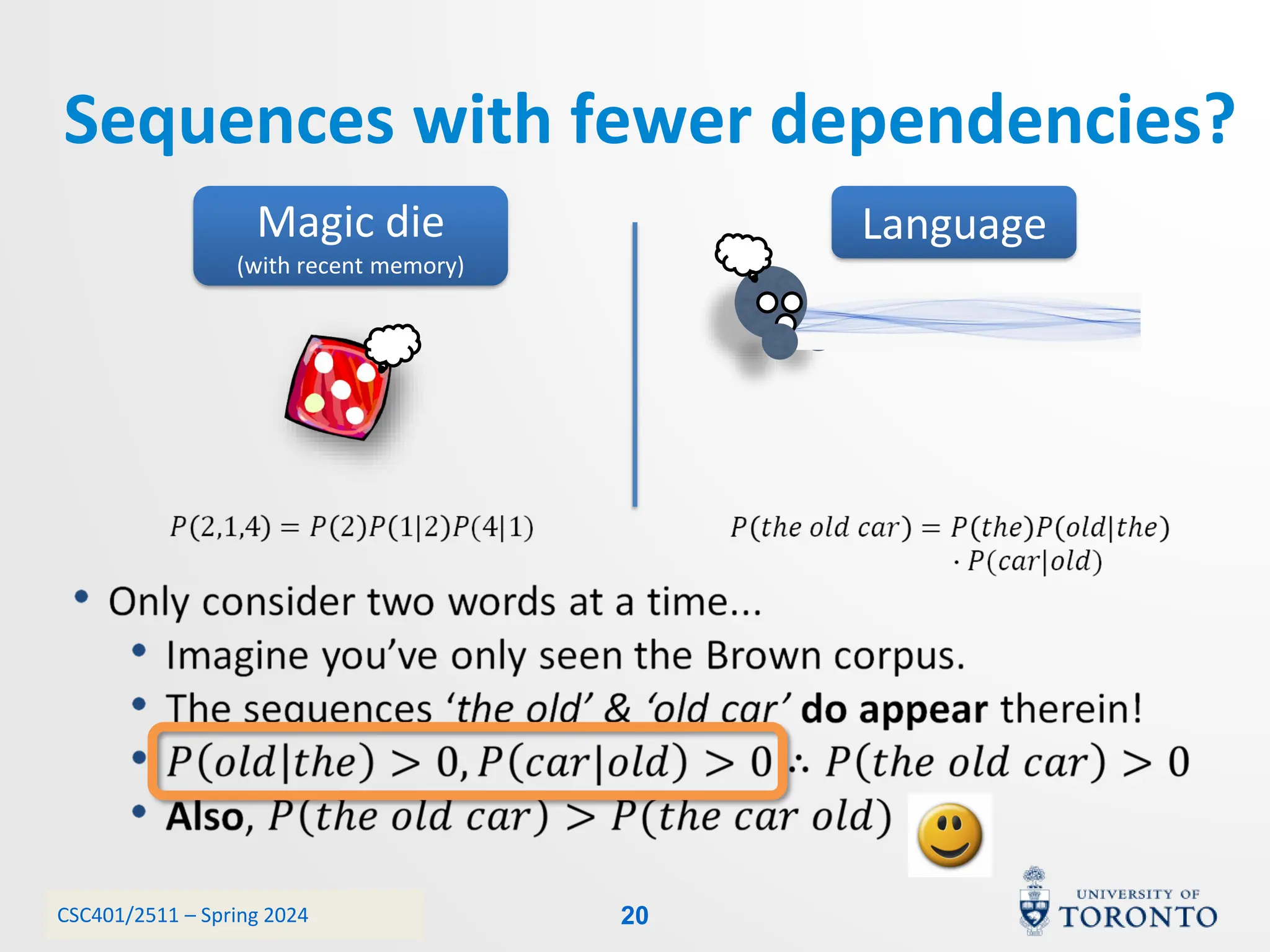

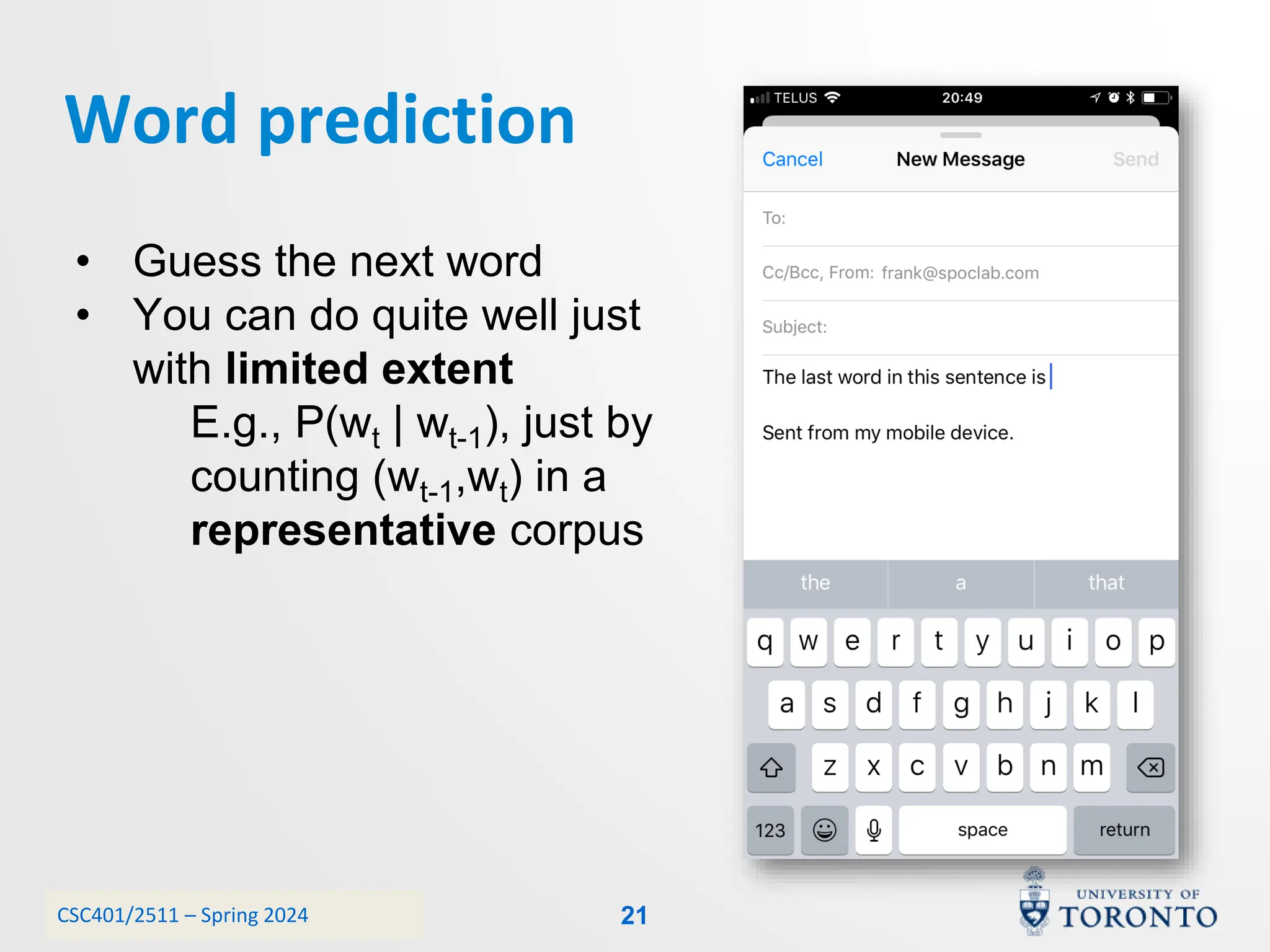

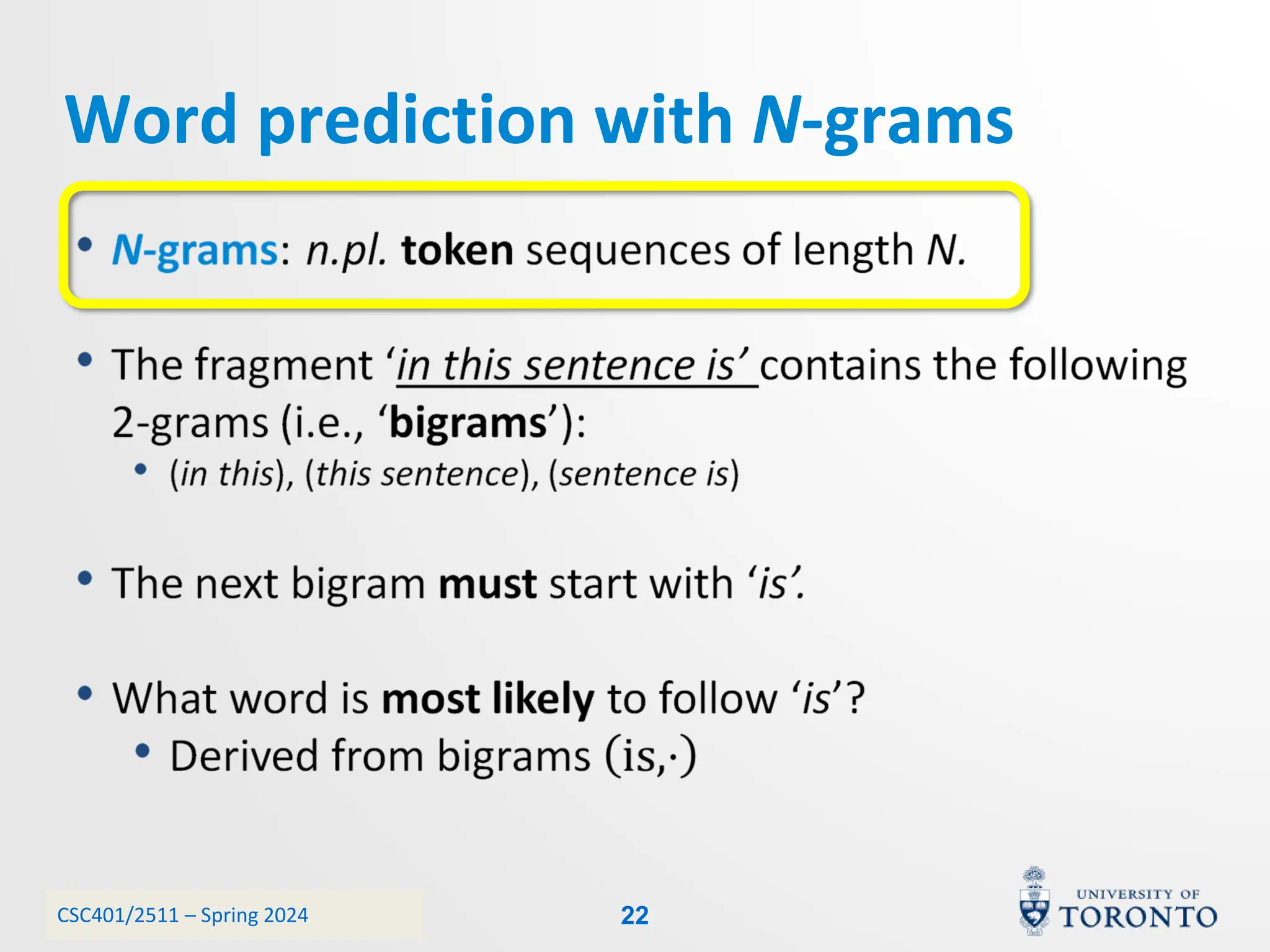

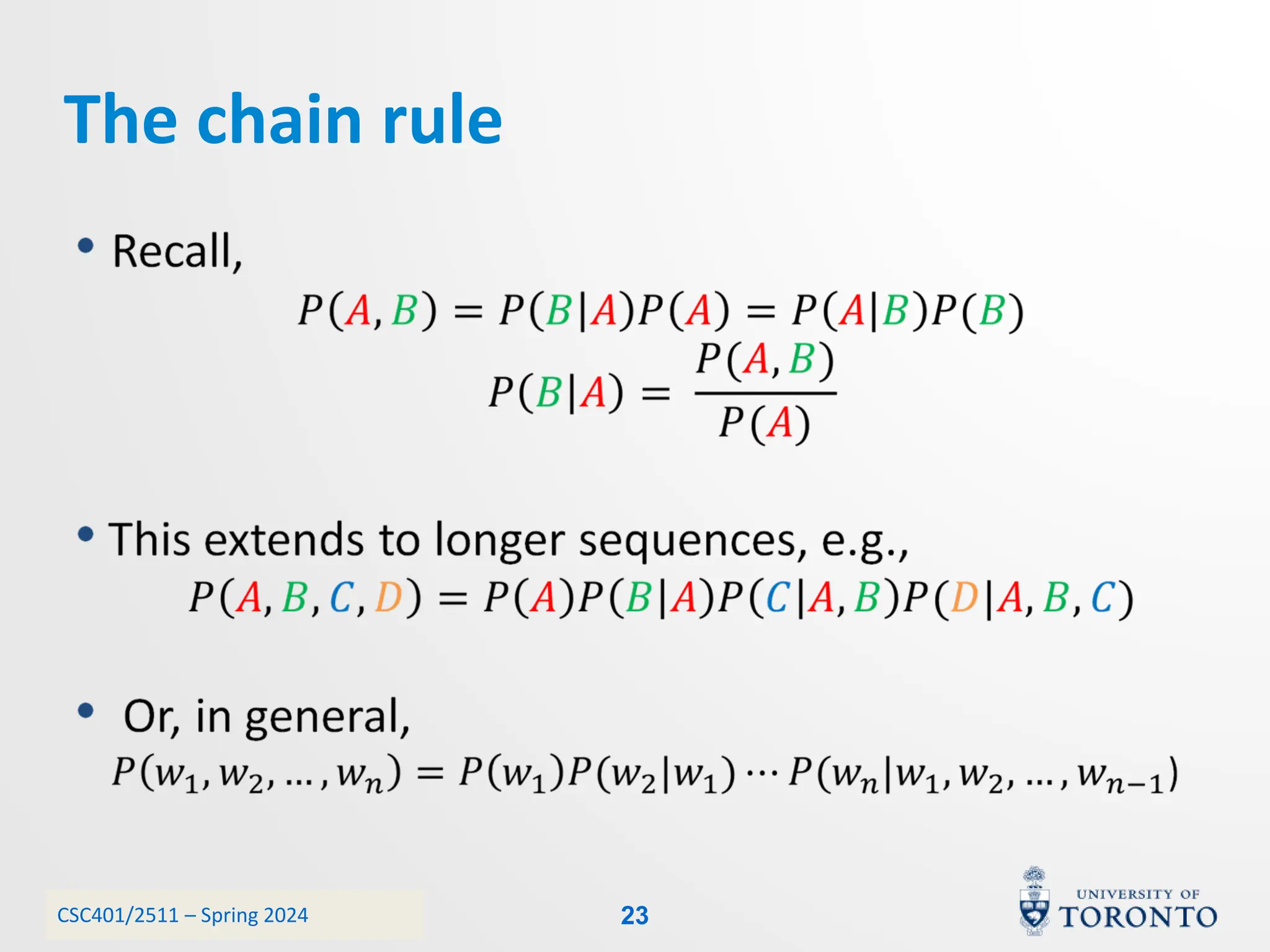

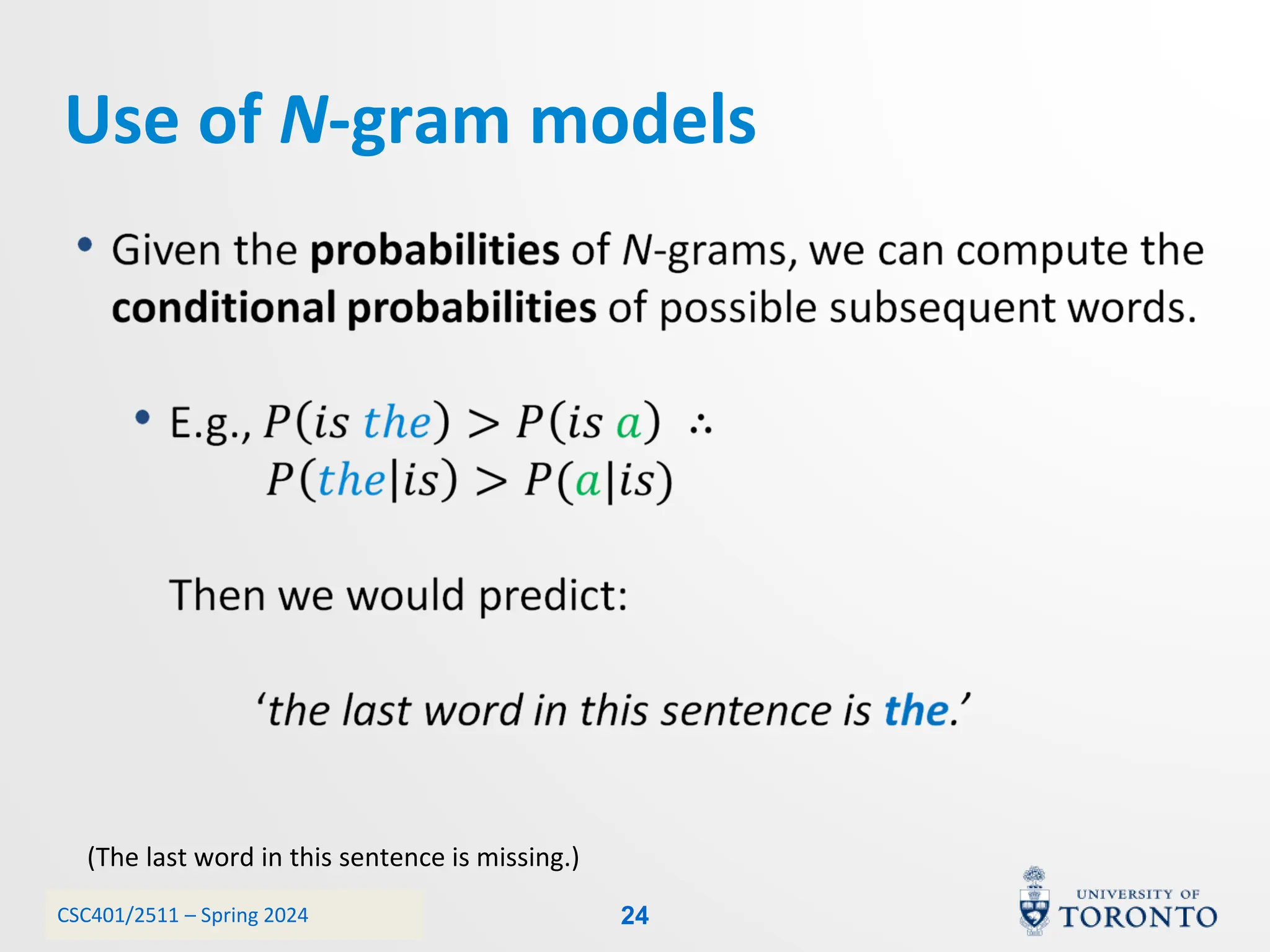

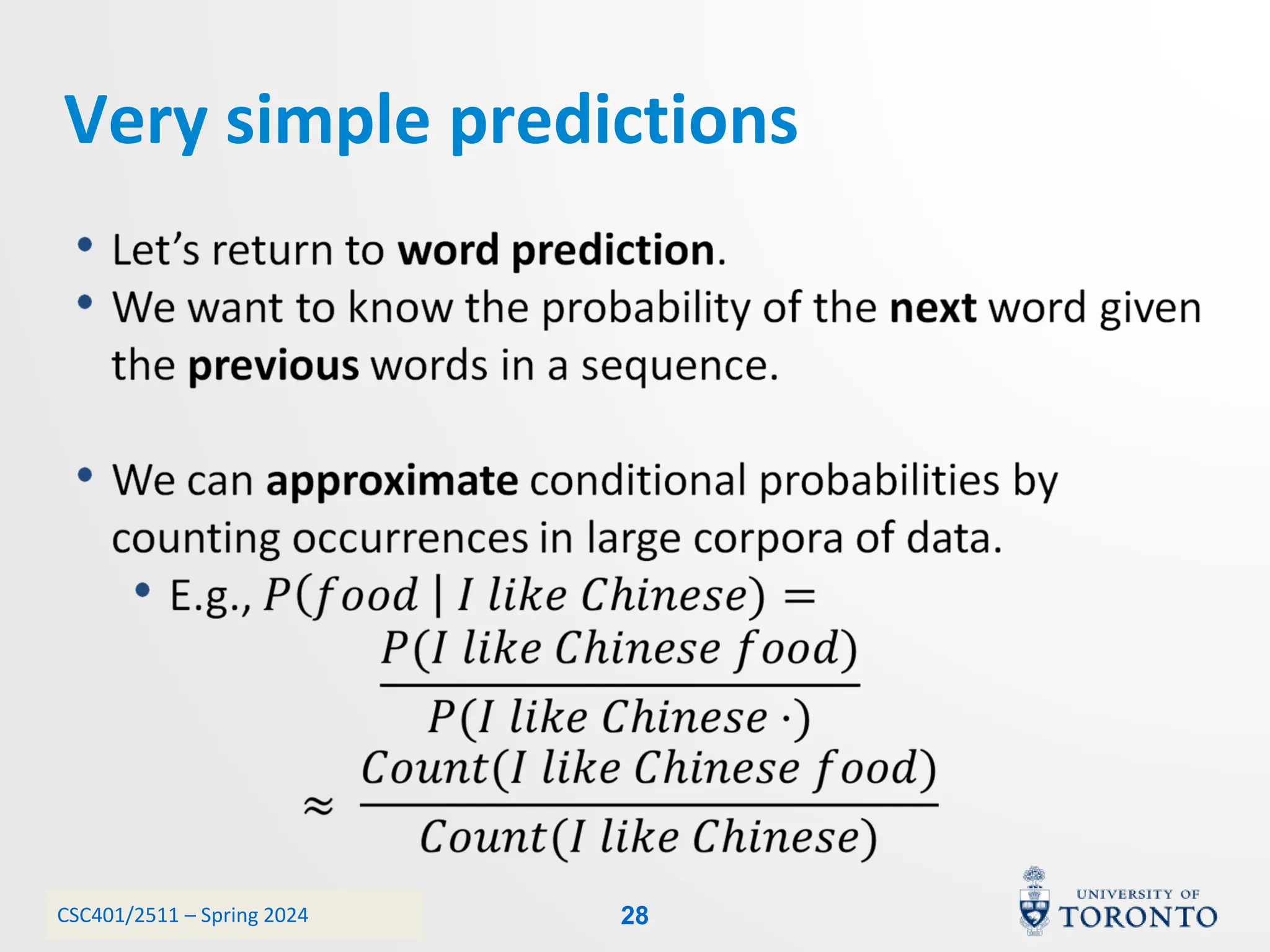

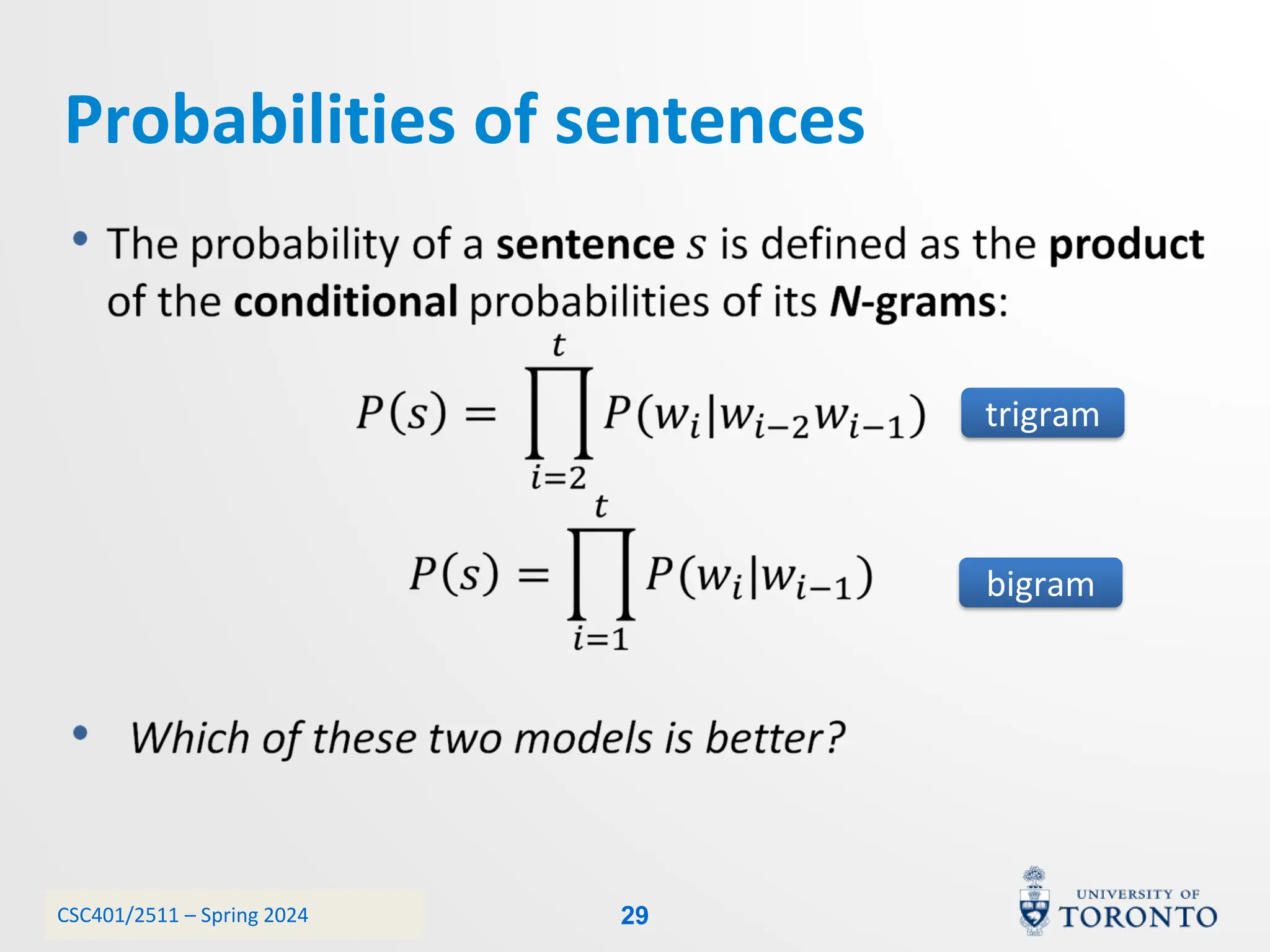

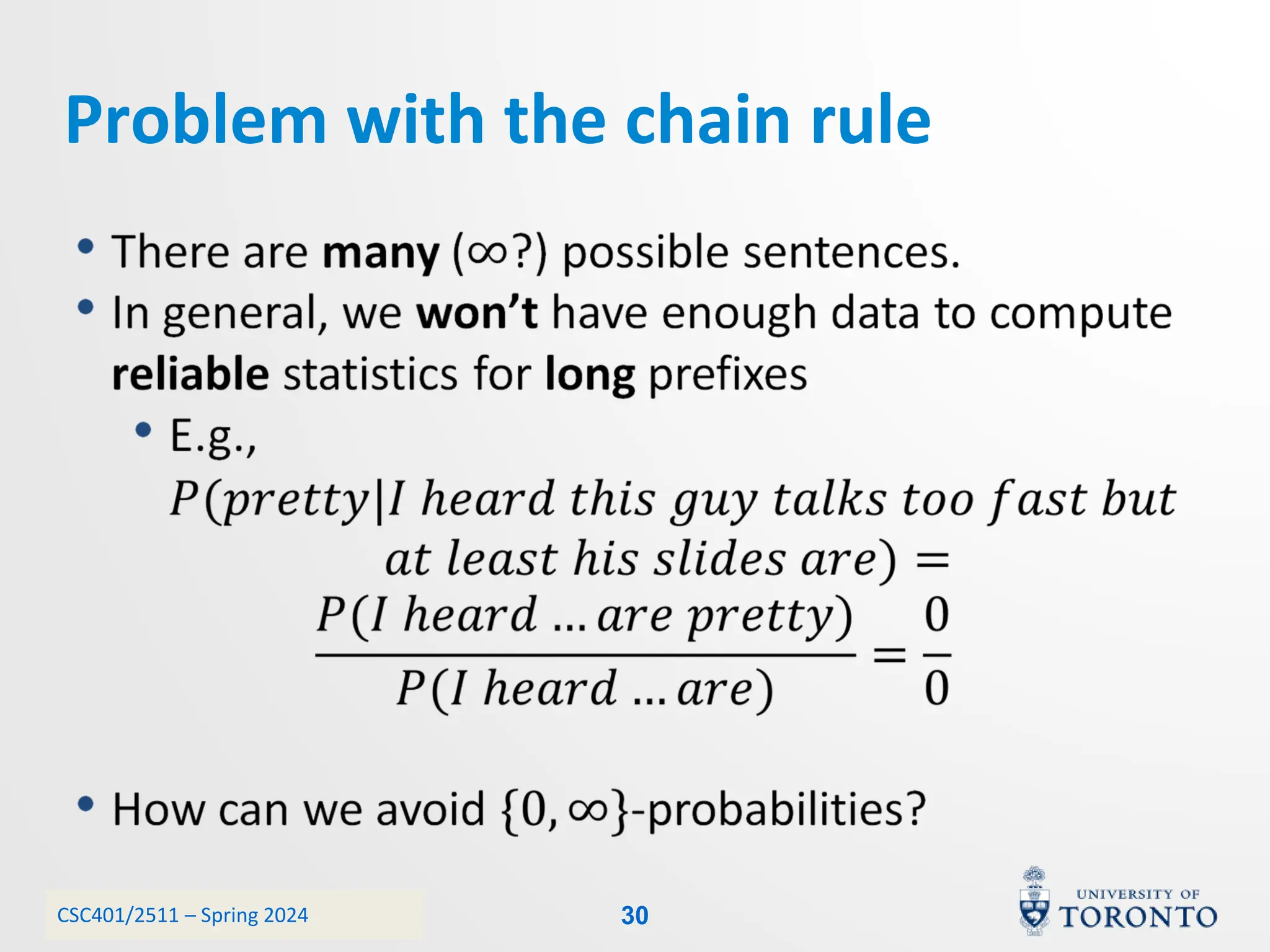

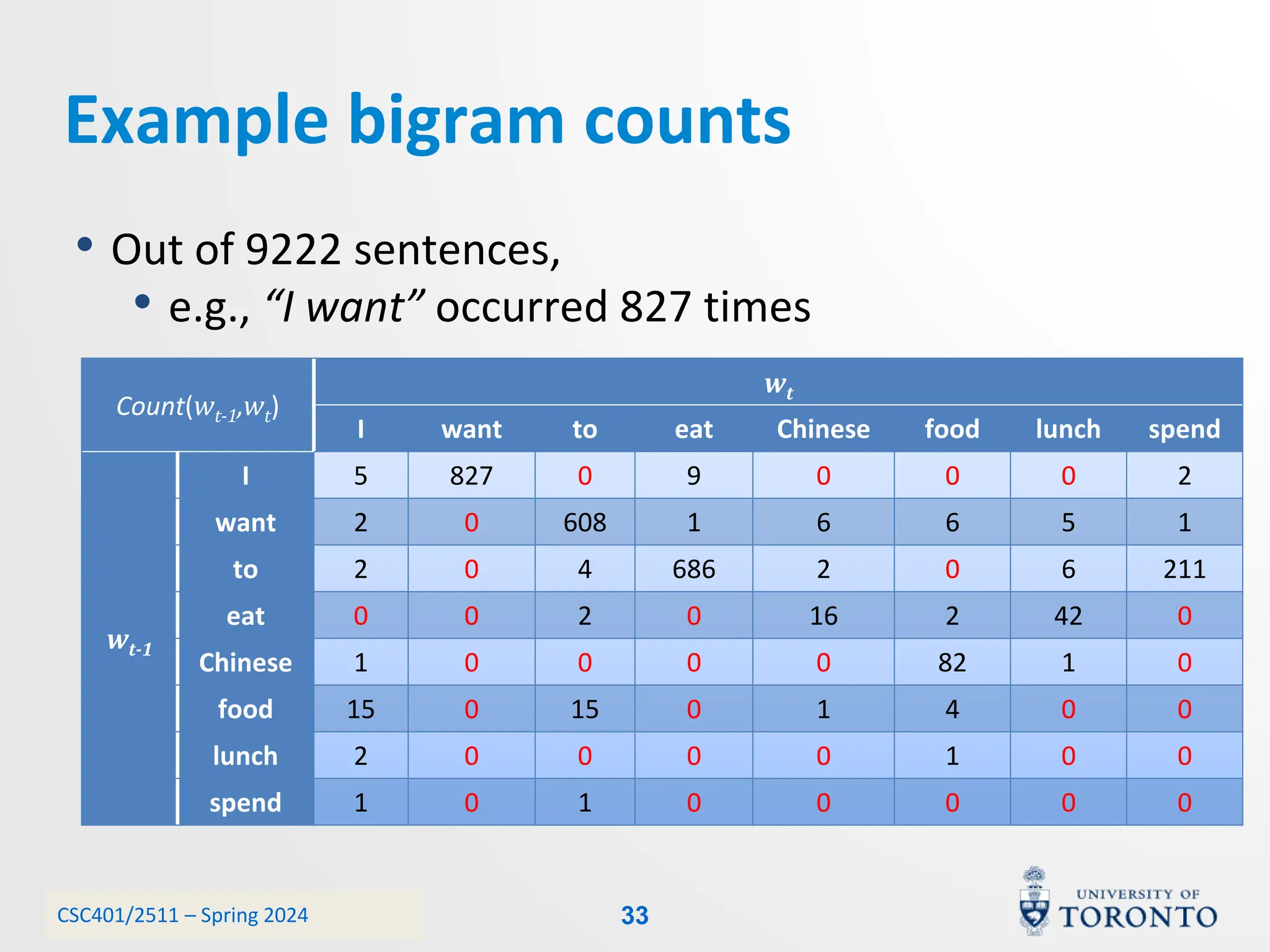

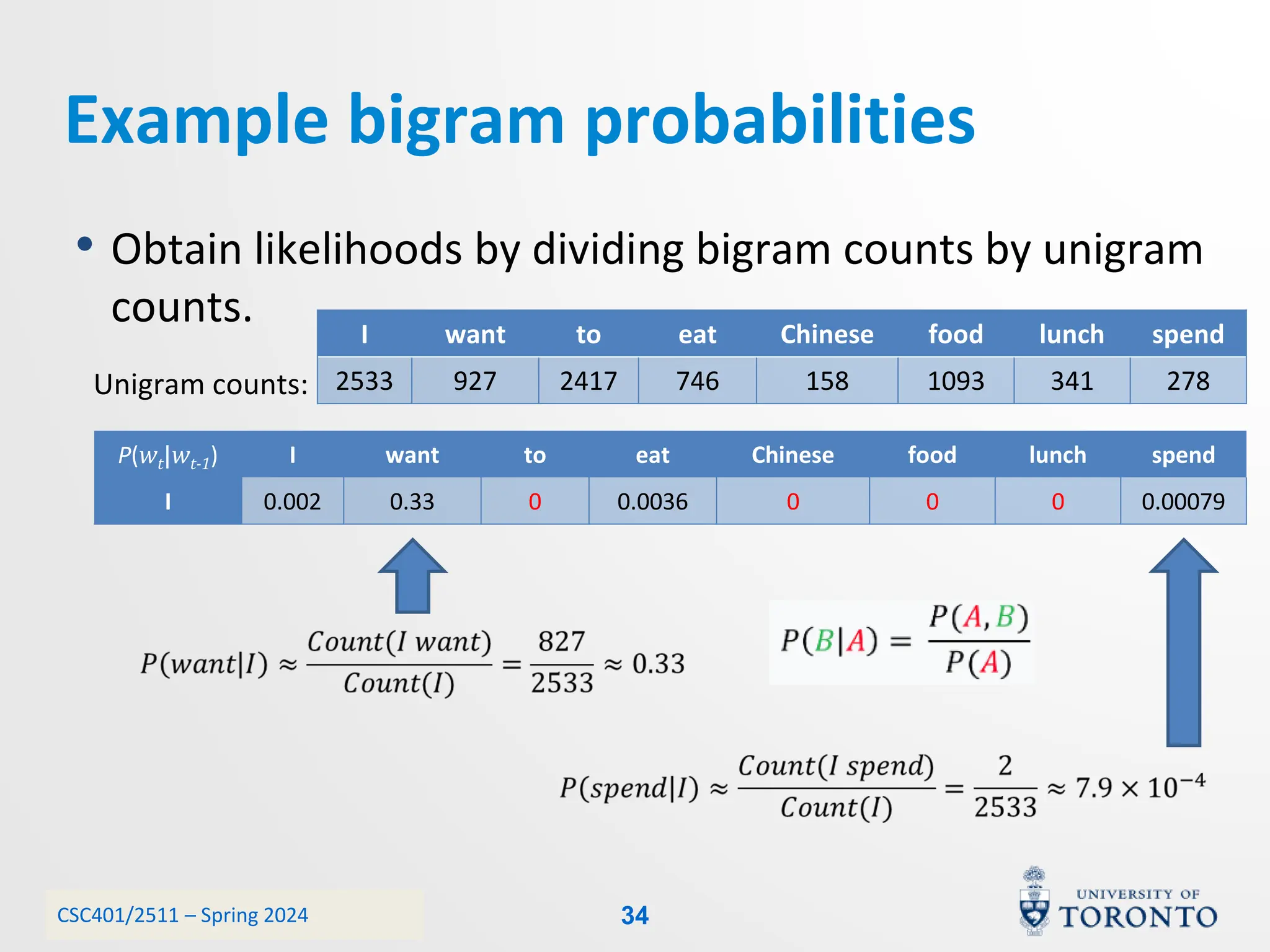

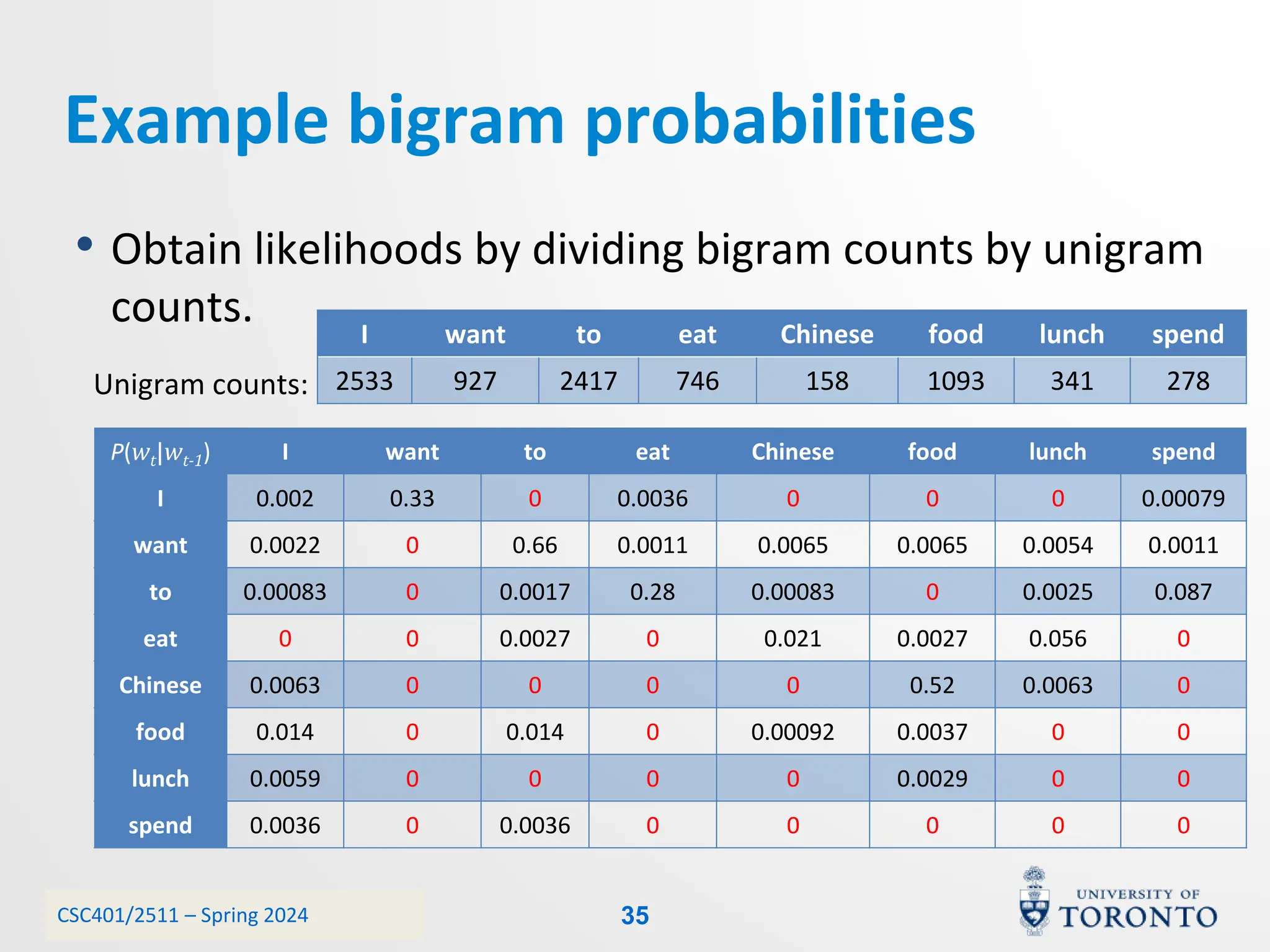

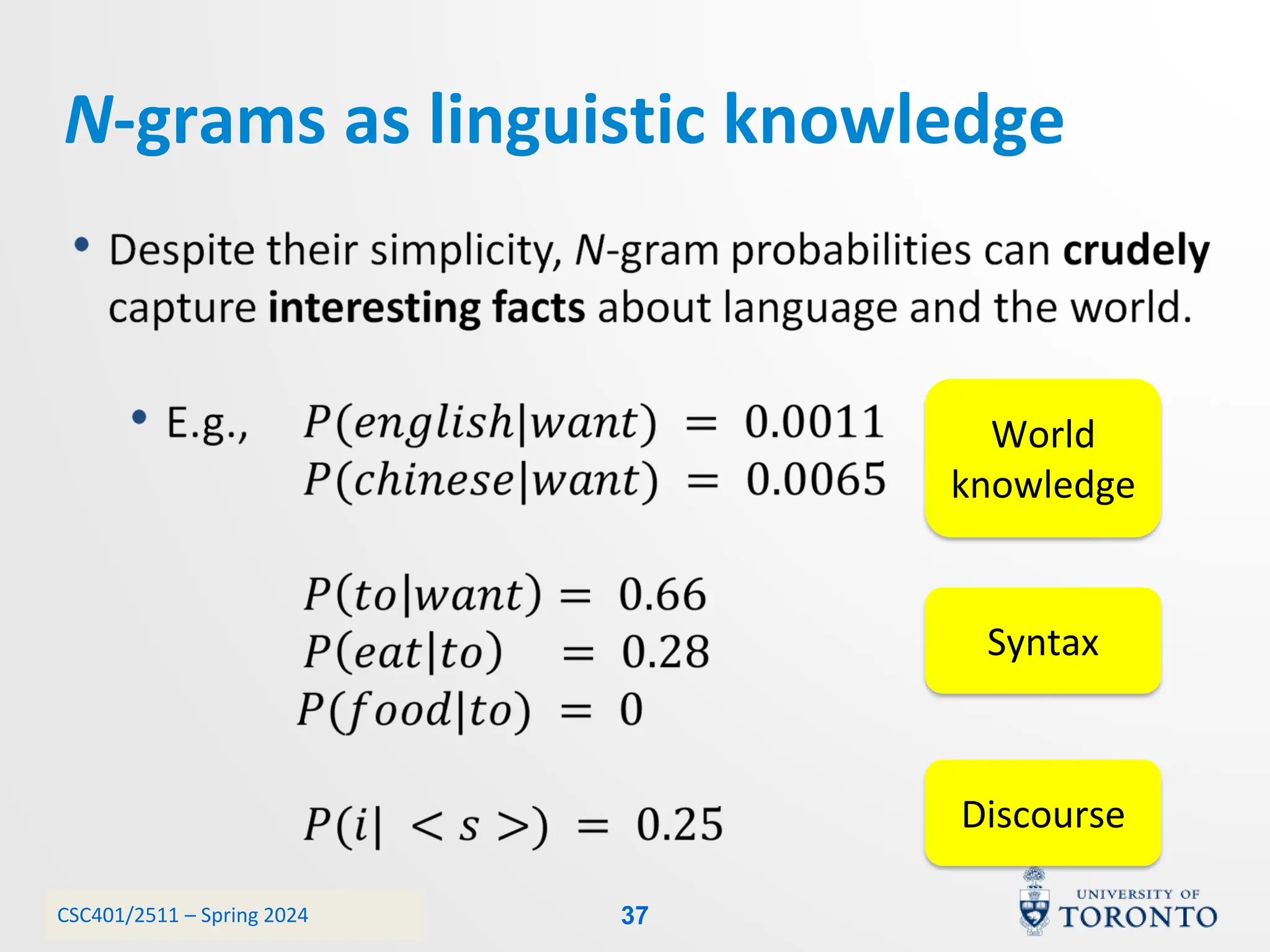

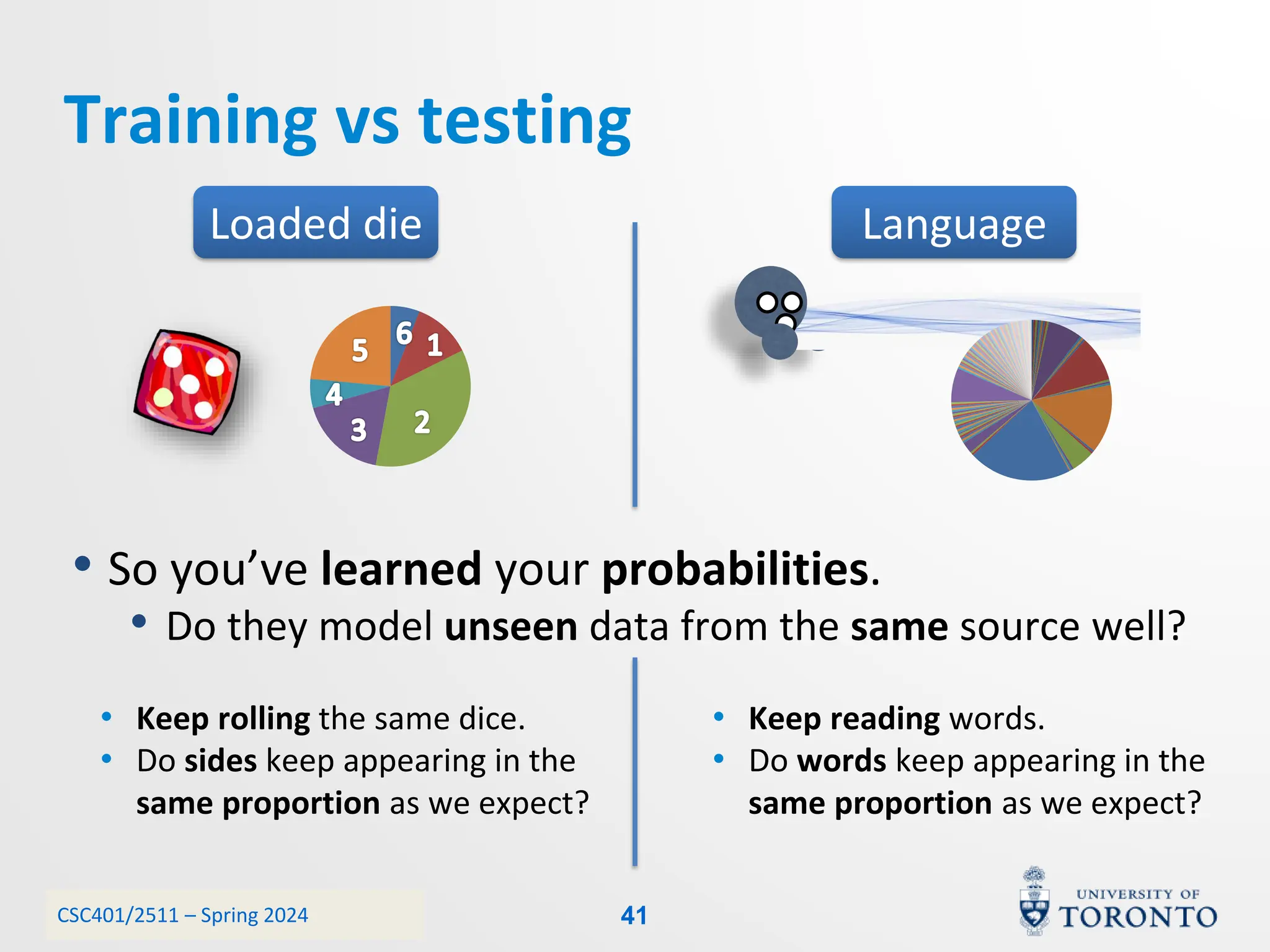

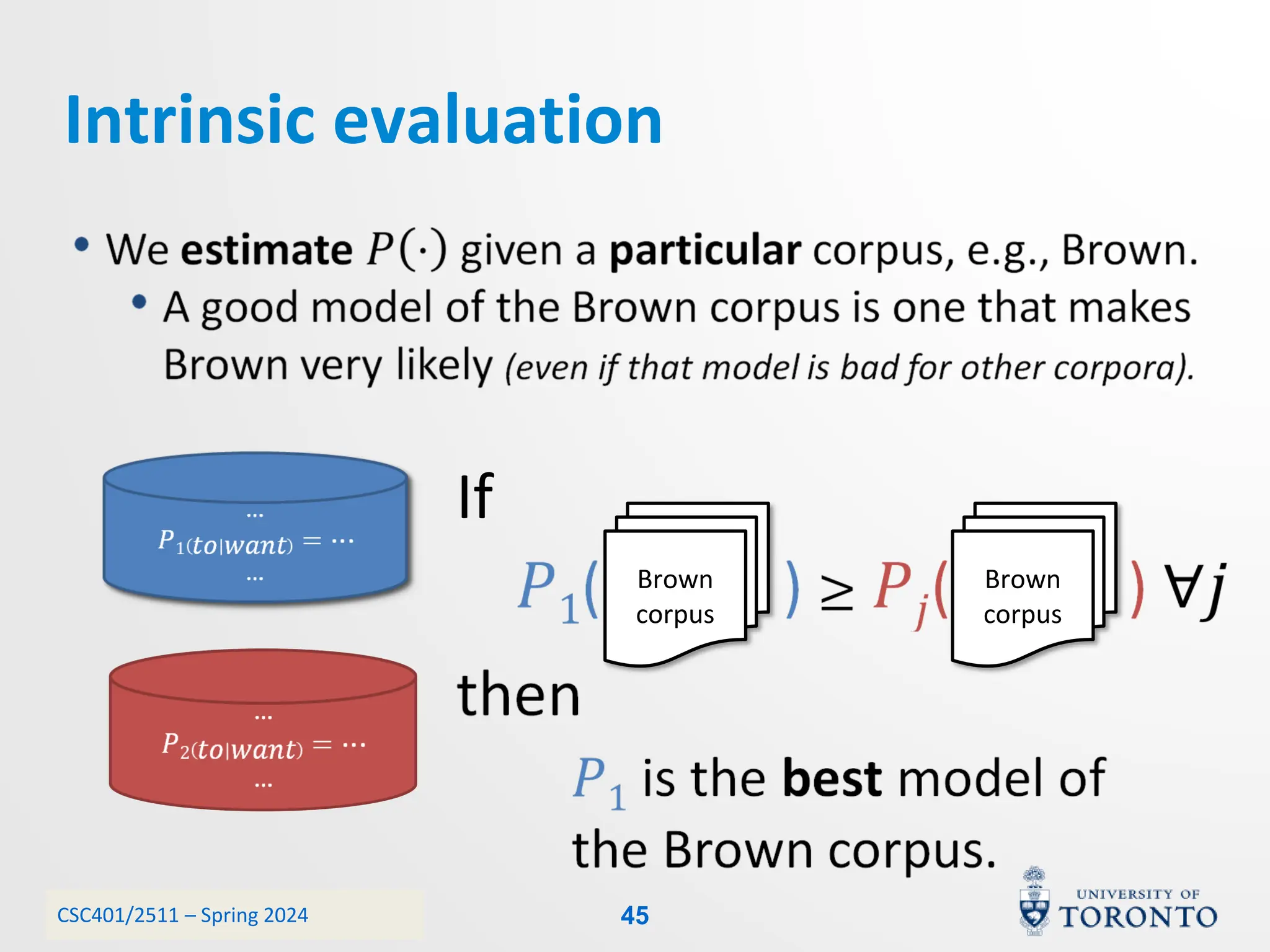

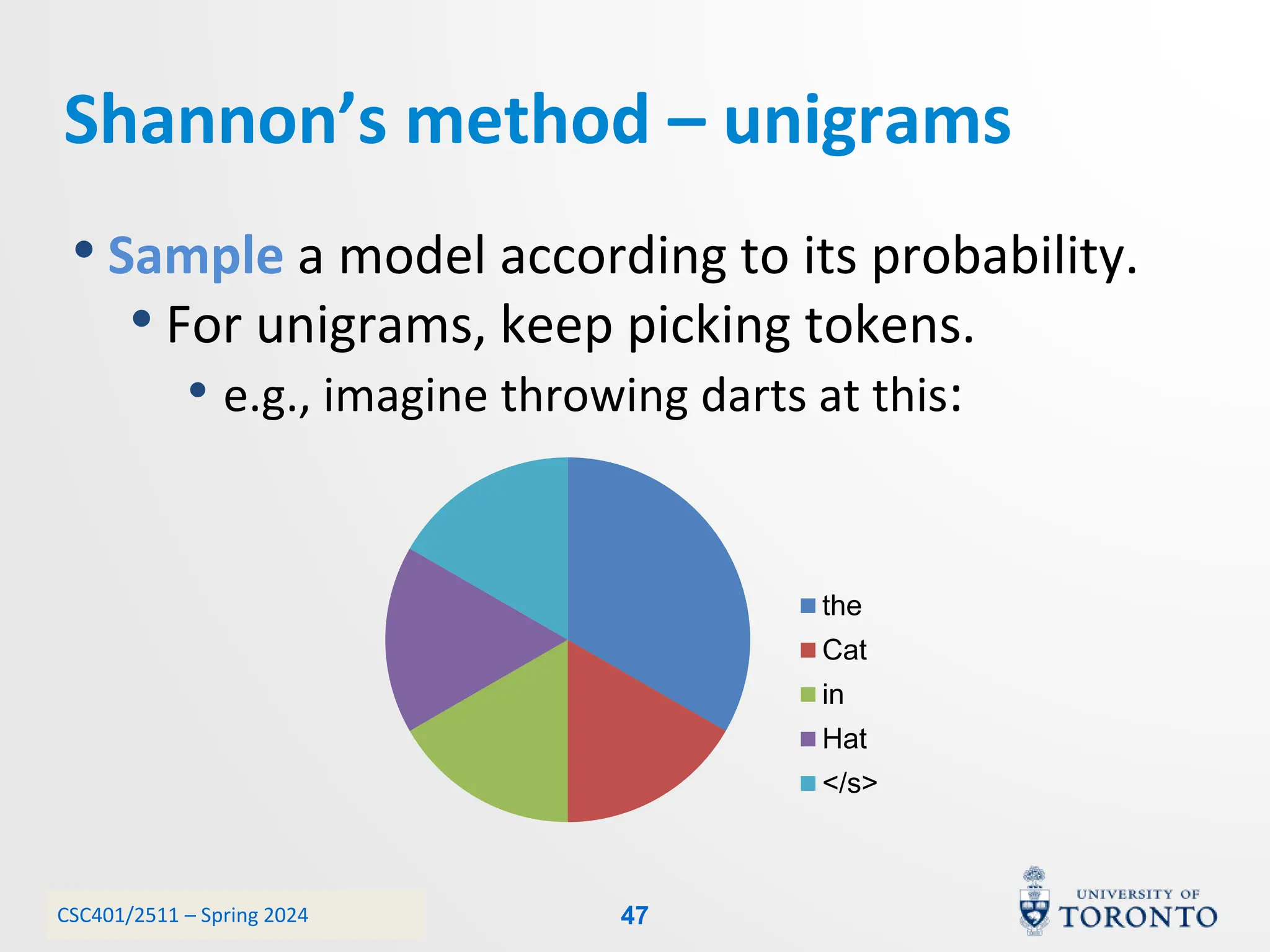

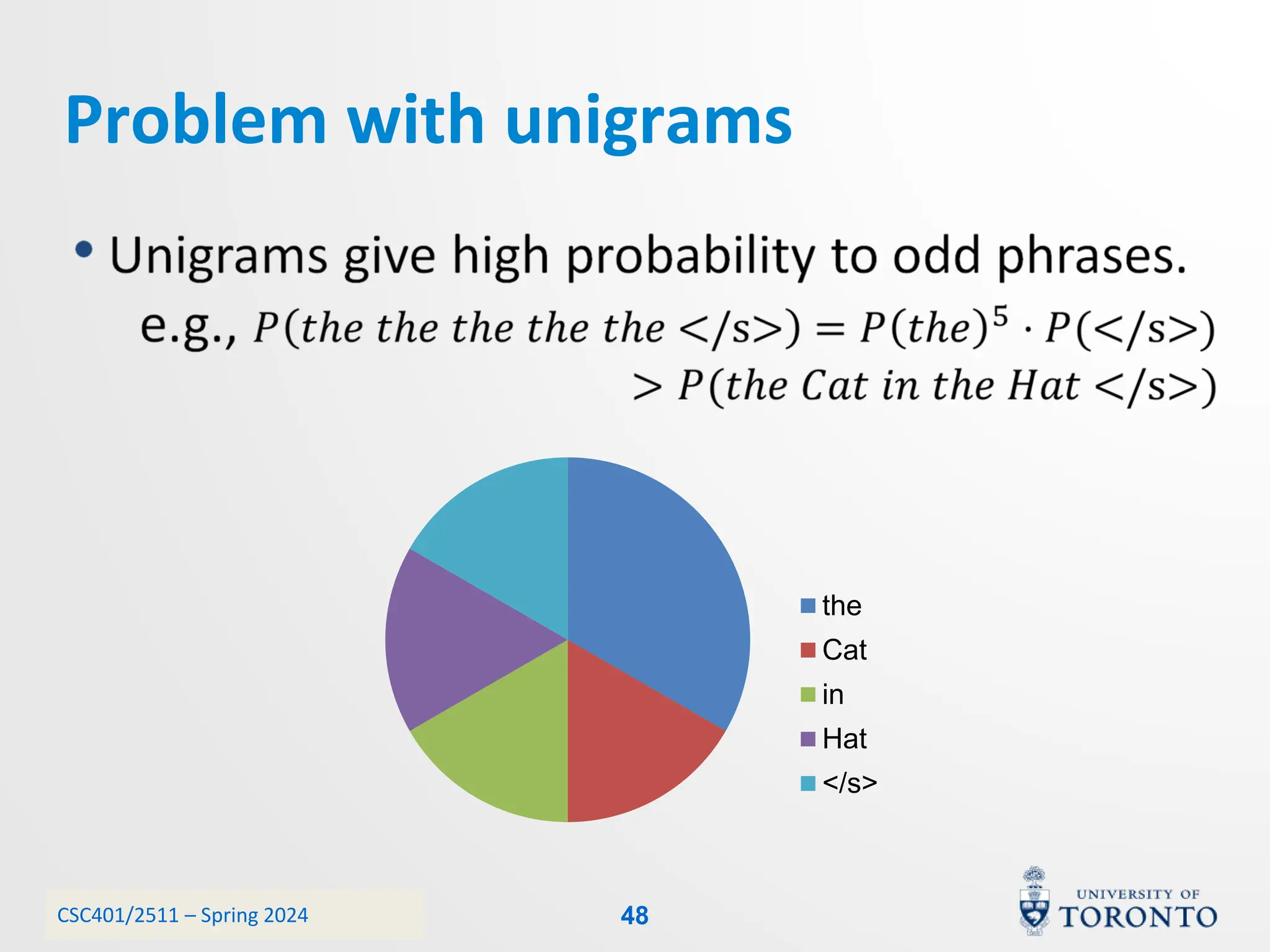

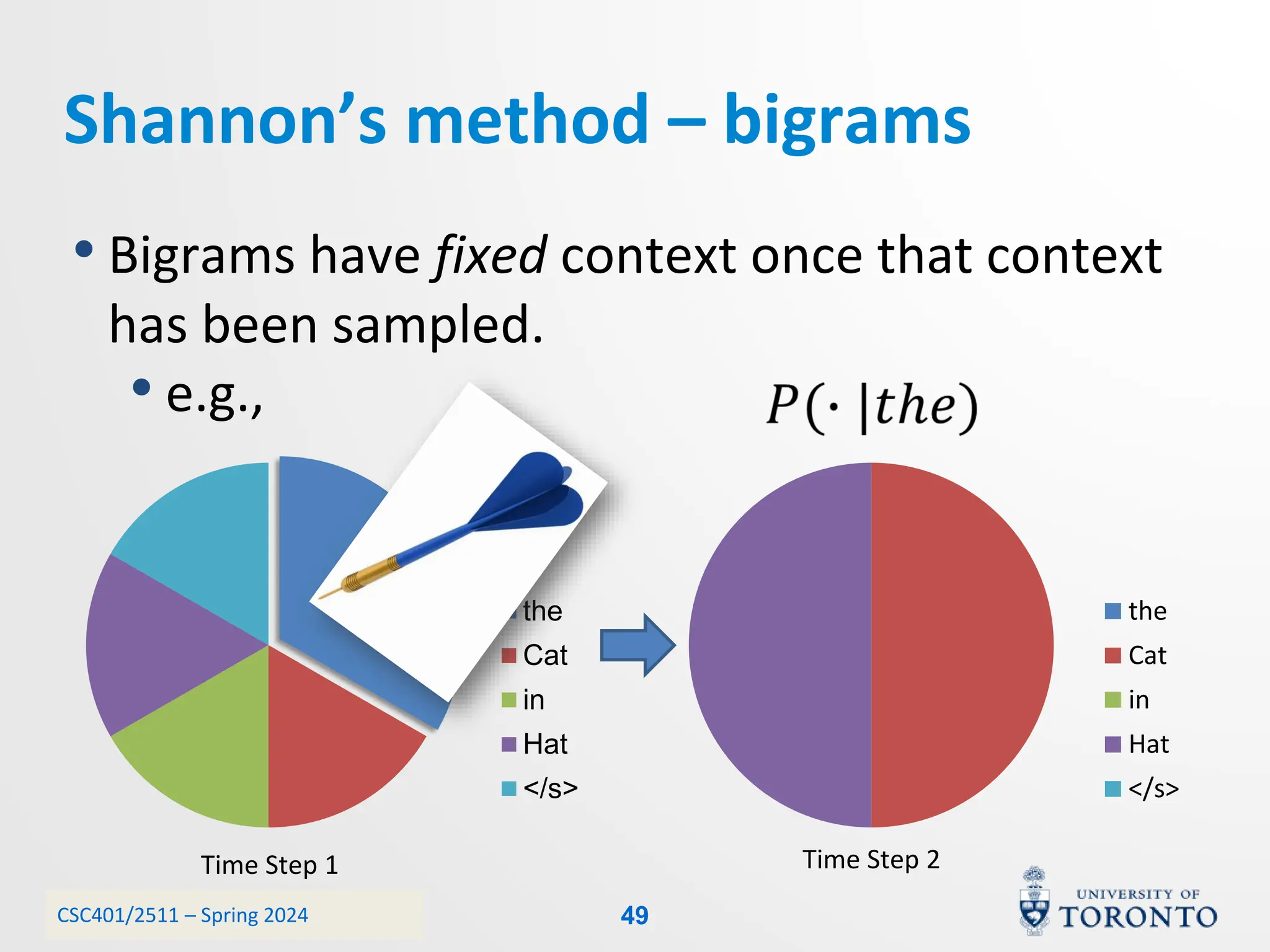

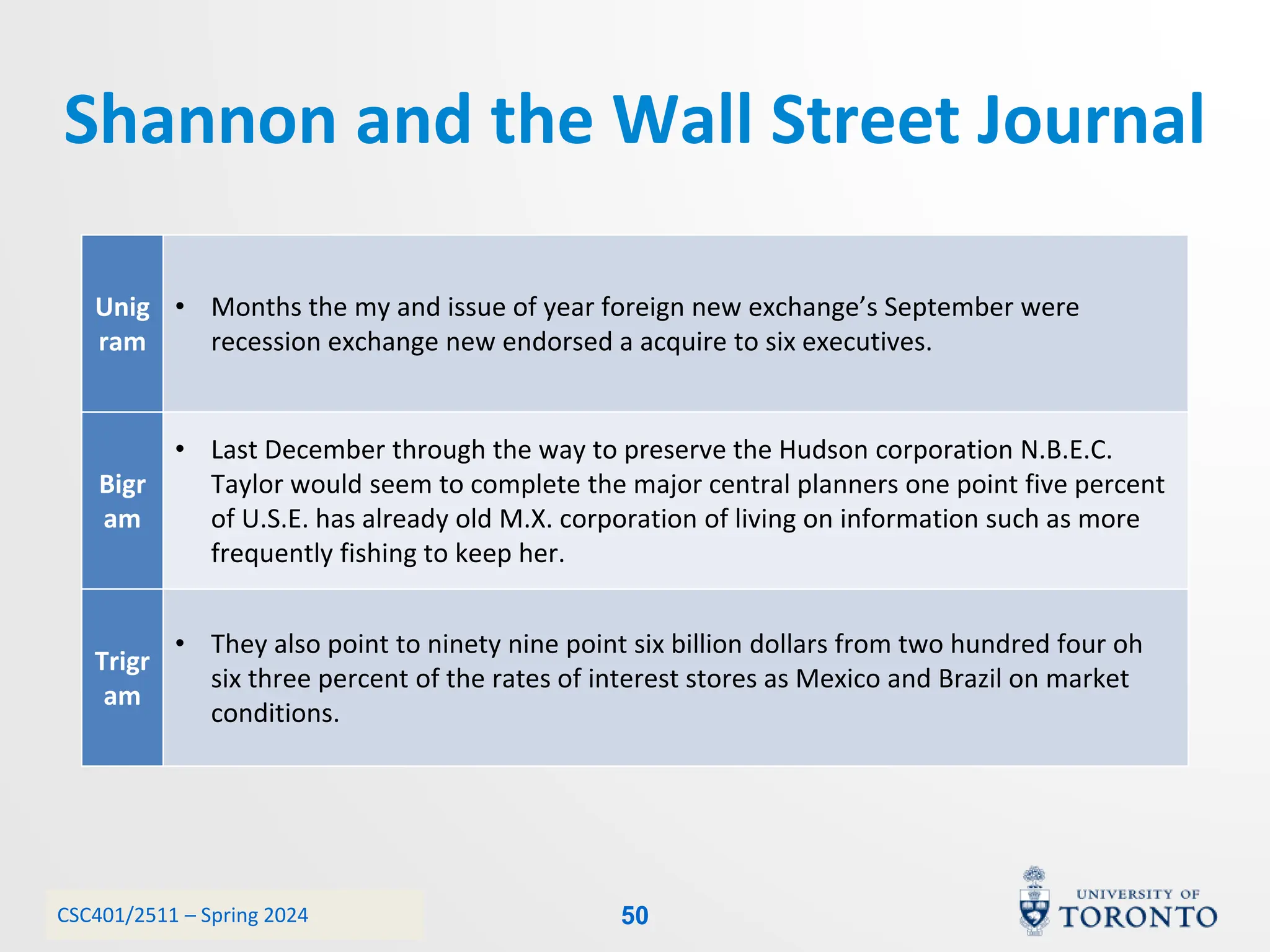

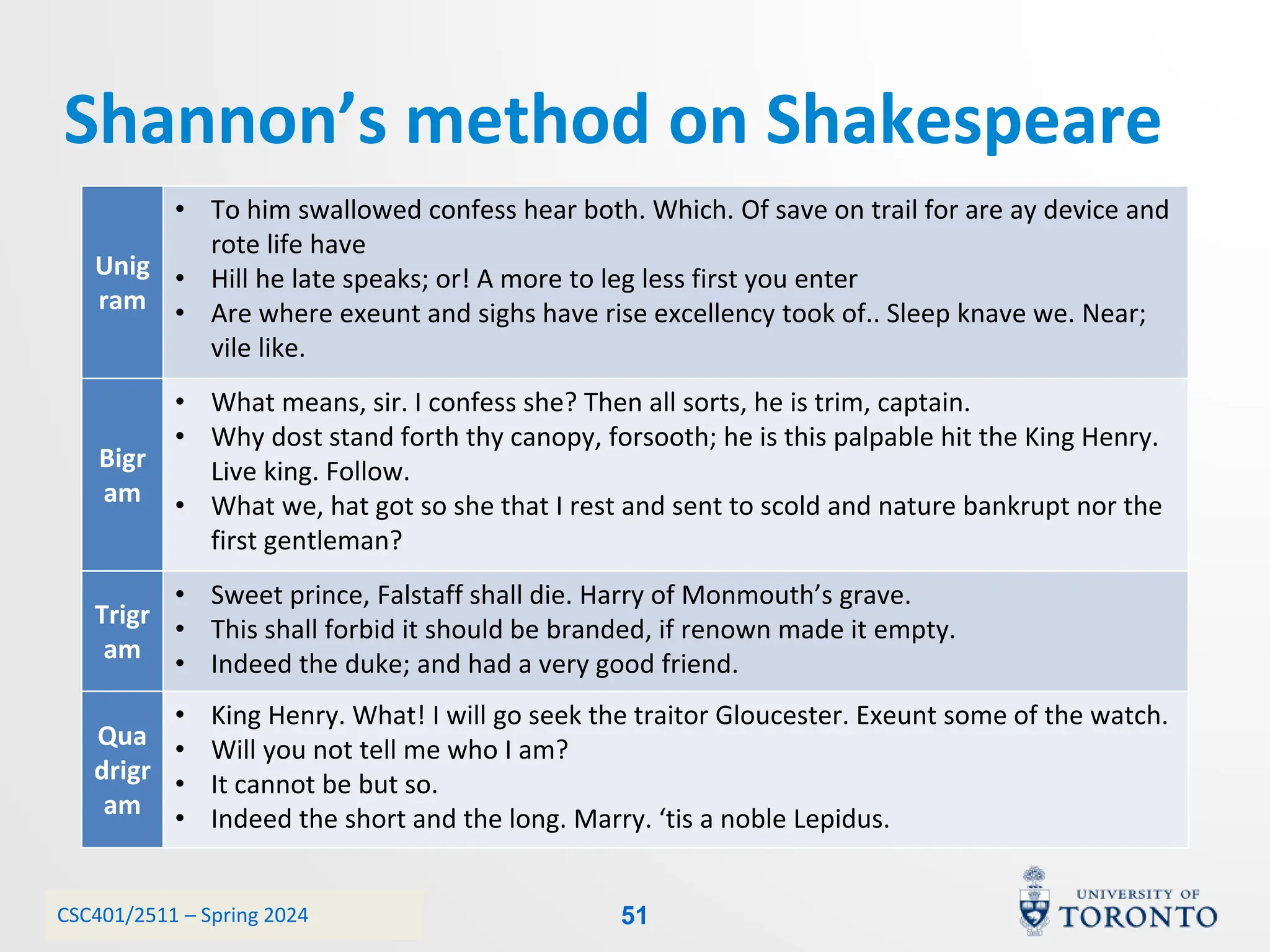

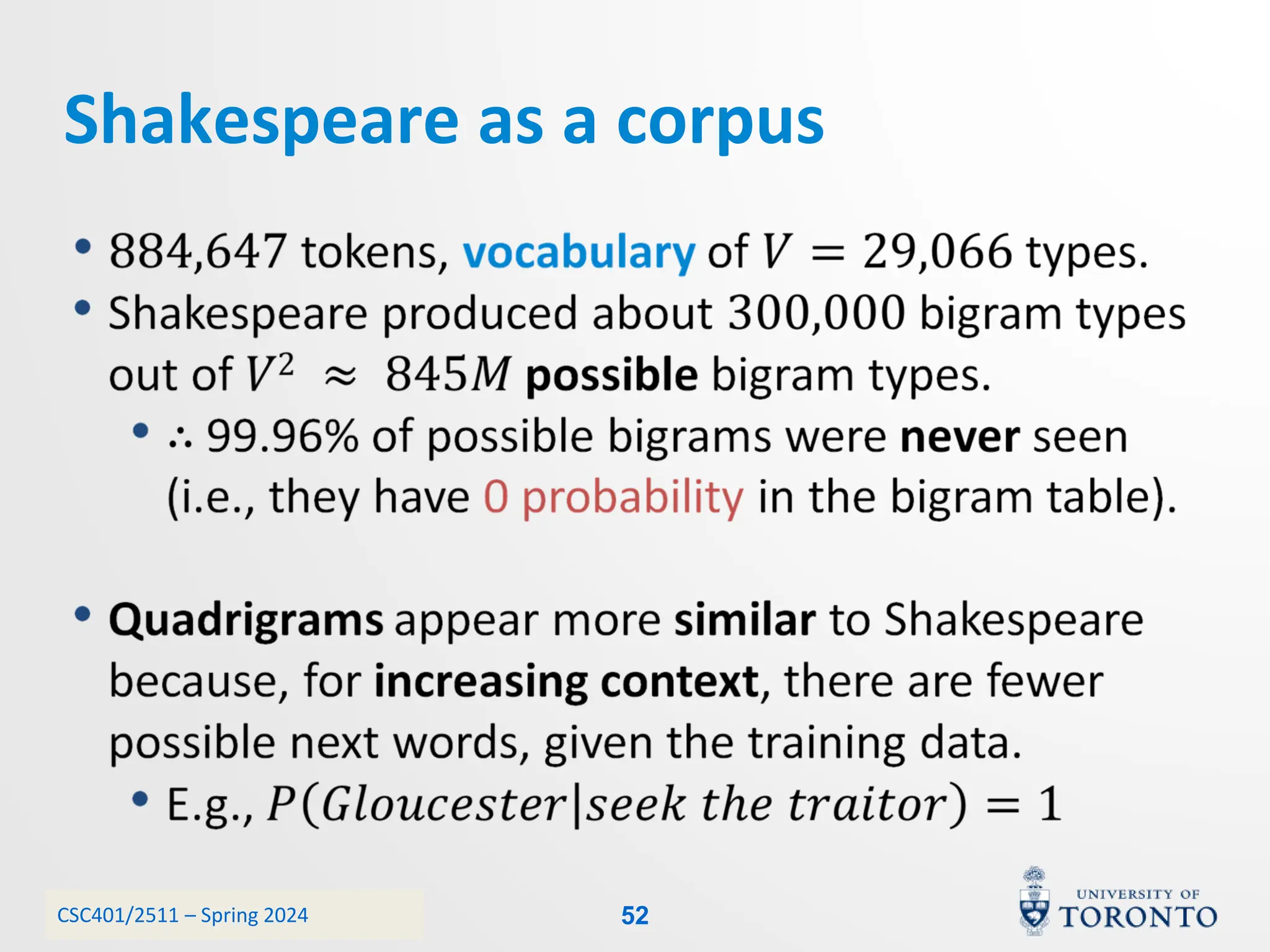

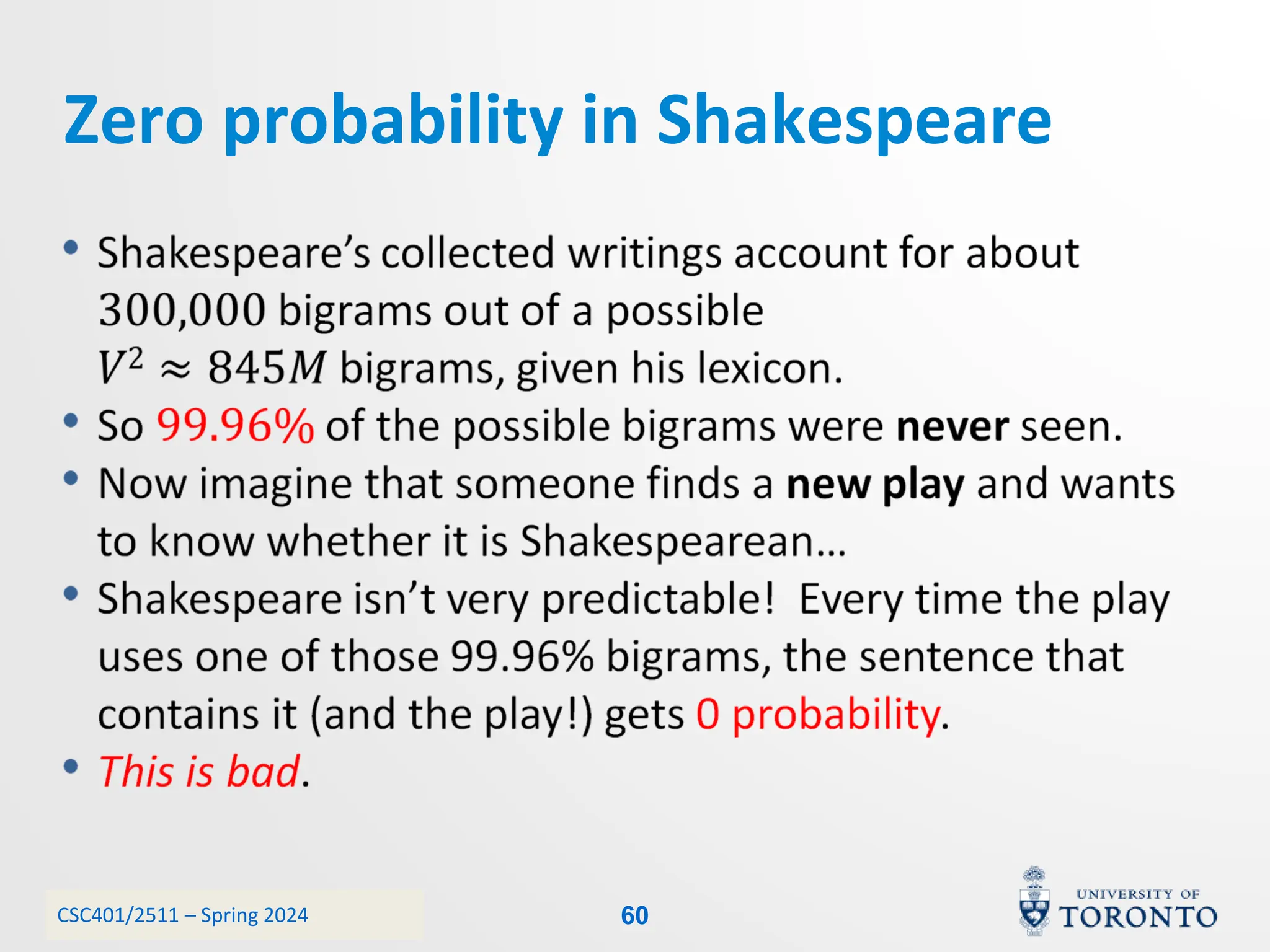

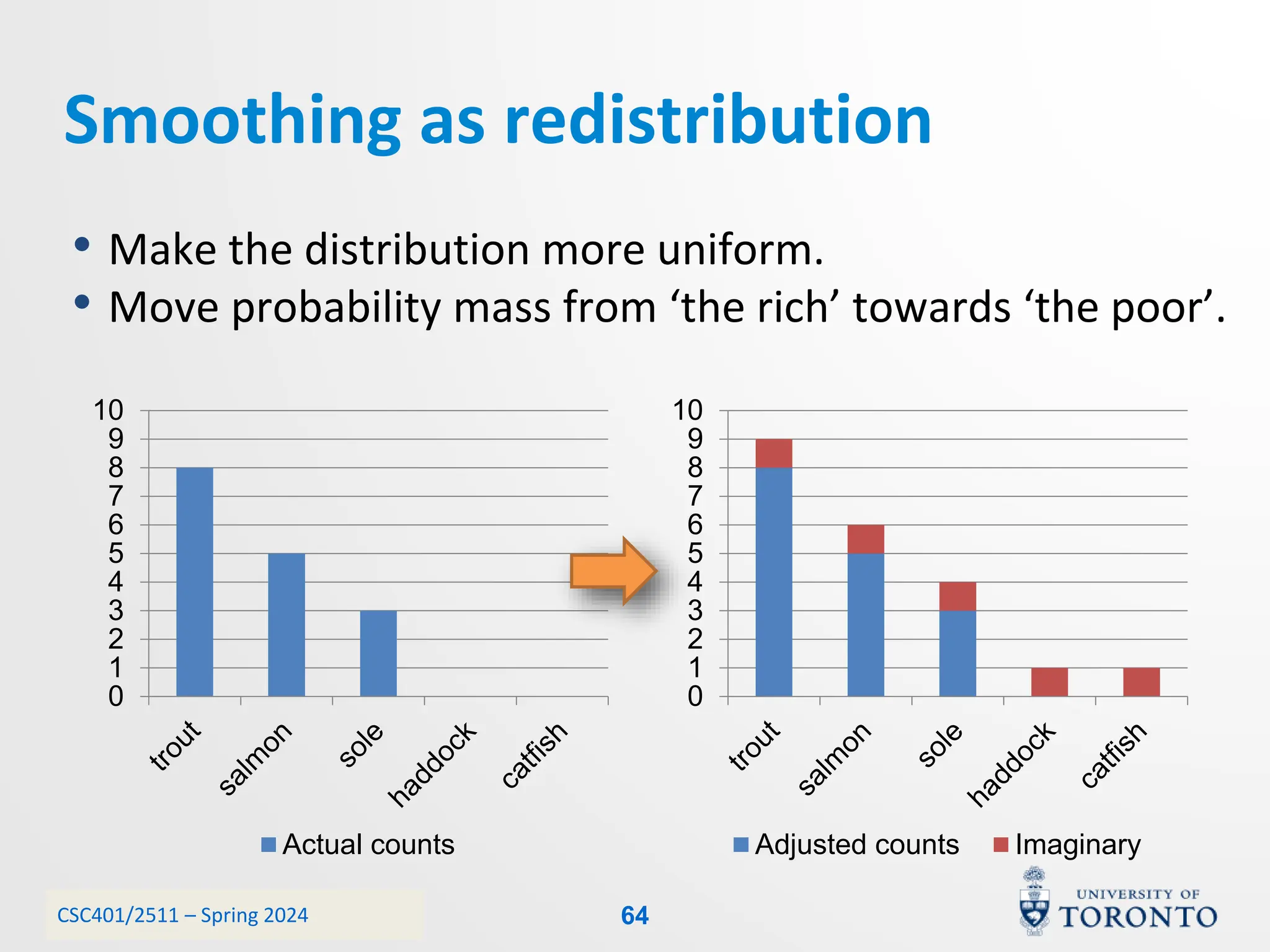

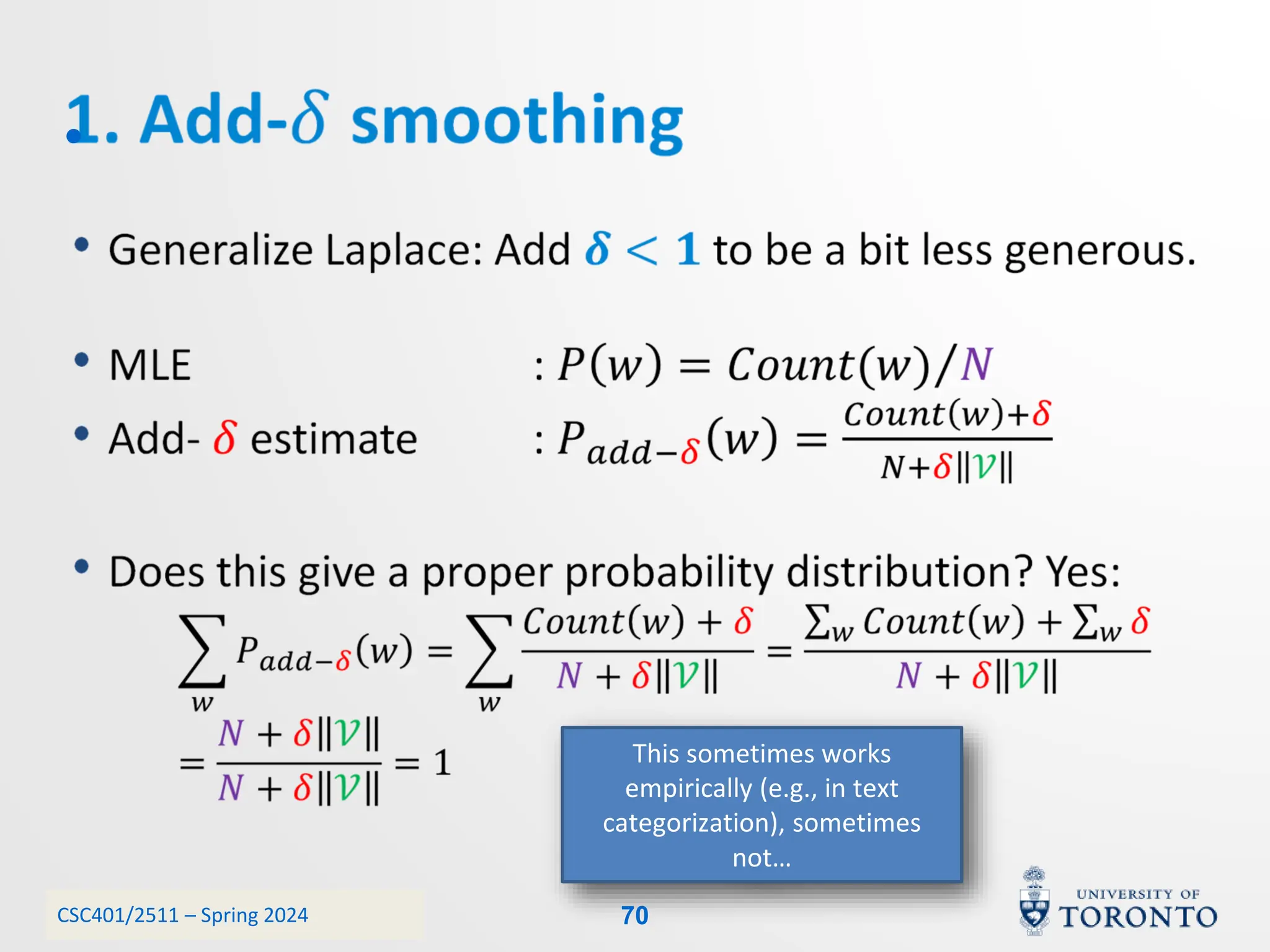

This document discusses corpora, language models, and smoothing techniques for natural language processing. It begins by defining corpora as collections of natural language data used to gather statistics about language. It then discusses Zipf's Law, which notes that a few words are very frequent while many words are rare. The document introduces n-gram language models which predict the next word based on the previous n words. It notes issues with n-gram models like zero-probability events. The document then discusses smoothing techniques like Good-Turing discounting used to redistribute probability mass from frequent to rare events to address zero-probabilities.