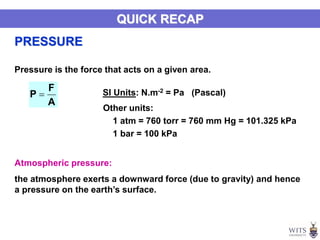

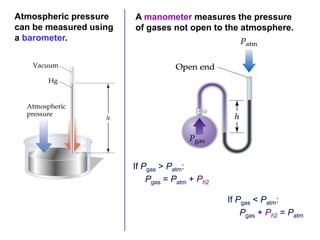

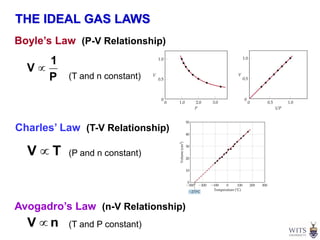

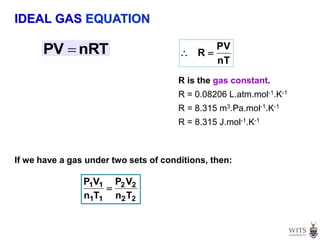

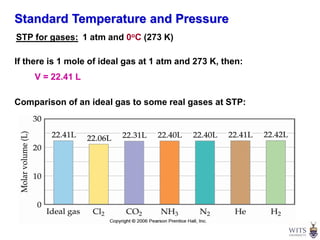

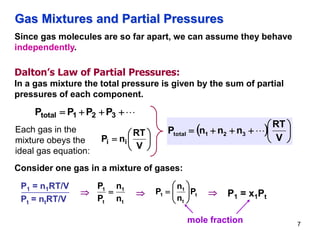

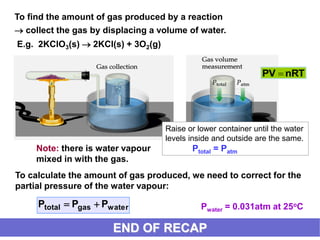

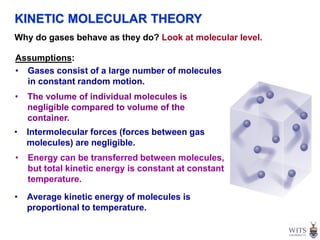

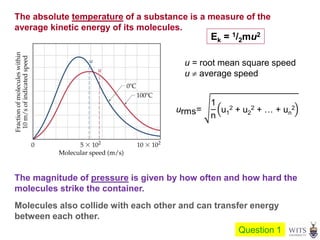

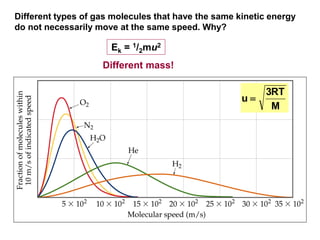

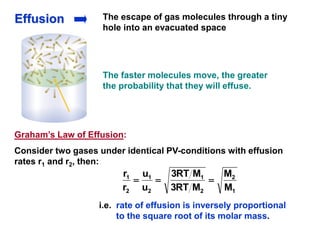

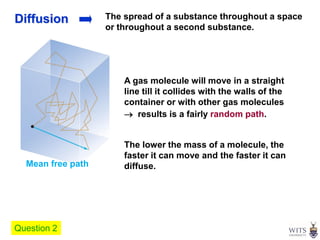

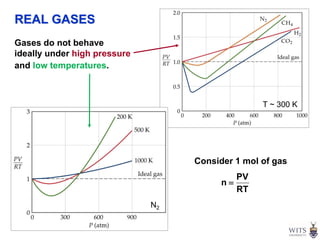

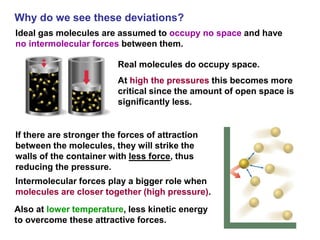

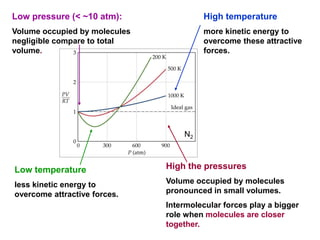

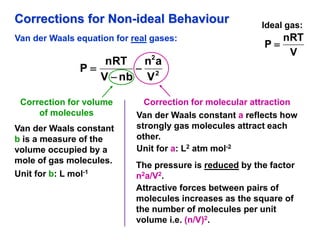

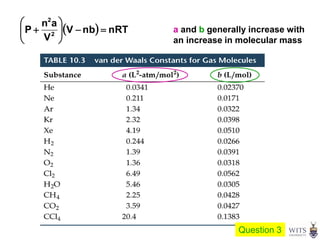

This document discusses gases and gas laws. It begins by defining pressure and discussing atmospheric pressure and how it can be measured. It then covers the three main gas laws (Charles' Law, Boyle's Law, Avogadro's Law) and combines them into the ideal gas equation. The document also discusses gas mixtures and partial pressures, kinetic molecular theory, effusion and diffusion of gases, deviations from ideal behavior at high pressures/low temperatures, and uses the van der Waals equation to account for real gas behavior.