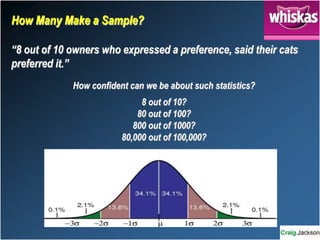

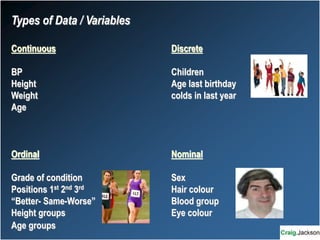

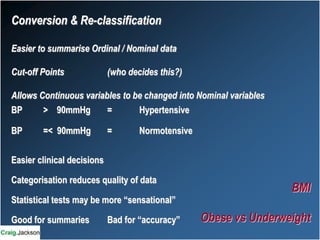

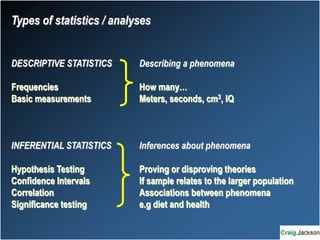

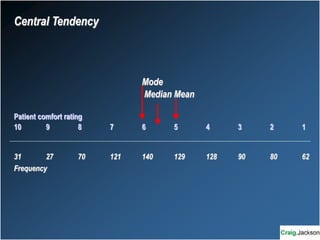

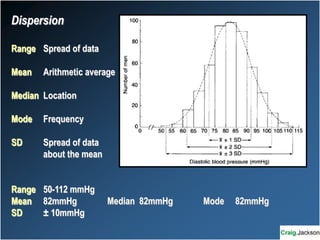

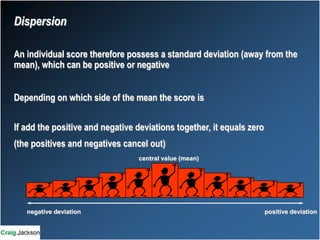

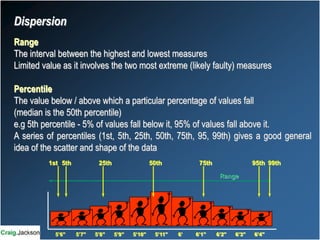

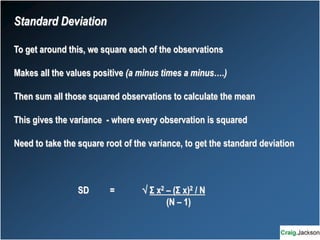

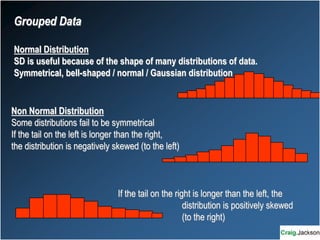

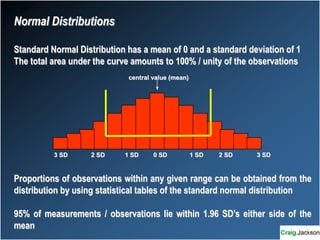

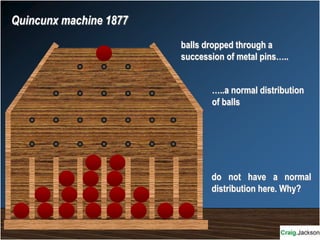

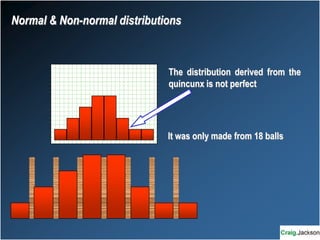

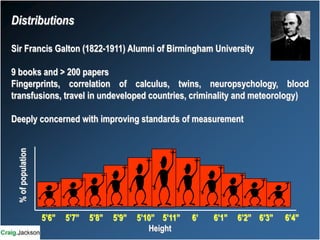

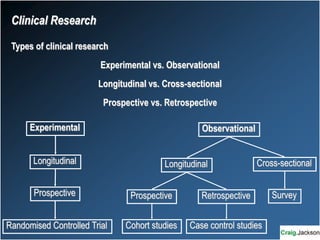

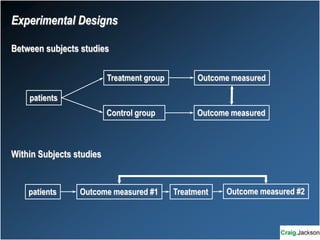

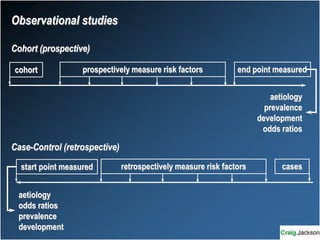

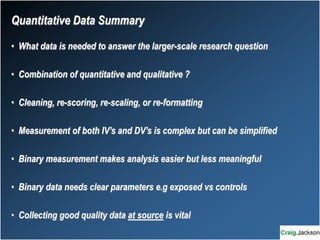

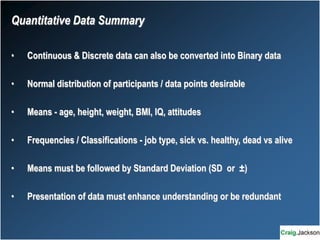

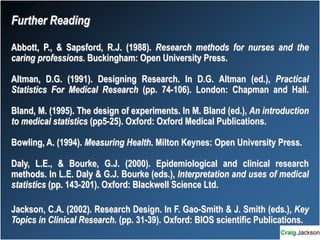

This document provides an overview of key statistical concepts for non-statisticians. It defines different types of data and variables, different ways of displaying and summarizing data, measures of central tendency and dispersion, normal and non-normal distributions, and different types of clinical research studies. The goal is to introduce basic statistical concepts in an accessible way for those without a statistics background.