This research investigates the pressure drop characteristics of both single-phase and aqueous-organic two-phase flow through rectangular serpentine millichannels, focusing on the use of packed and unpacked configurations. Experimental results are presented alongside empirical models aimed at predicting pressure drop and friction factors based on various operating conditions. The findings are significant for enhancing the understanding and design of multiphase systems in microfluidic applications, particularly for extraction processes in chemical and pharmaceutical industries.

![Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Experimental Thermal and Fluid Science

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/etfs

Frictional pressure drop of aqueous-organic two-phase flow through packed

and unpacked rectangular serpentine millichannel

Somen Mondal, Subrata Kumar Majumder

⁎

Department of Chemical Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati, Guwahati 781039, Assam, India

A R T I C L E I N F O

Keywords:

Serpentine channel

Frictional pressure drop

Friction factor

Millichannel

Packed channel

Liquid-liquid flow

A B S T R A C T

This research work depicts the pressure drop characteristics of single-phase as well as aqueous-organic liquid-

liquid two-phase flow through the rectangular serpentine millichannel in a horizontal orientation. Experiments

were performed to investigate the pressure drops for both single and immiscible two component liquid-liquid

aqueous-organic flows through the same rectangular serpentine channel with medium sand packing. The ex-

perimental results are enunciated with the available models for both empty and packed channels. Empirical

models are developed to predict the pressure drop and friction factor for both single and two-component liquid-

liquid flows through the prescribed serpentine geometry based on operating variables. The present work may be

useful for further understanding of the multiphase system in the serpentine micro-dimensional unit for its design

and development.

1. Introduction

Millichannel technologies with liquid-liquid flow have attracted

considerable attention in compact heat exchangers and mass transfer

devices in chemical industries. Liquid-liquid extraction is an important

mass transfer operation in the chemical, food processing and pharma-

ceutical industries. Essential oil from the natural sources dissolved in

alcoholic water can be extracted by an organic phase by continuously

passing the phases through the packed channel. The packed channel

facilitates high retention time of phases and regular mixing which

benefits the higher extraction rate. Liquid-liquid extraction using aqu-

eous-organic phase (water and butanol) is one of the important study

for intensification of extraction by microfluidic device in this context

[1]. Seibert and Fair [2] studied the influences of phase flow rates, the

direction of solute transfer, and phase dispersion in spray and packed

liquid-liquid extraction column. They developed a fundamental model

to account dispersed phase holdup, and mass-transfer efficiency with

two widely different chemical systems: toluene/acetone/water and 1-

butanol/succinic acid/water. Esmaeilzadeh et al. [3] studied the

spearmint oil extraction in a packed bed using SC-CO2 and its analysis

by mathematical modeling. Sahu et al. [4] studied the overall extrac-

tion performance characterizing as a function of the residence time of

the phases and the hydrodynamics. They reported that the micro-

channel can be a superior extraction device in the slug flow regime as

compared to the well-mixed batch system having comparable sizes of

the dispersed phase. They stated that the strong internal circulations

induced by shear in the slug flow regime attributed to the fact. Priest

et al. [5] demonstrated microfluidic solvent extraction of metal ions

from particle-laden aqueous solutions as an alternative to conventional

solvent extraction for the extraction of Cu2+

using 2-hydroxy-5-non-

ylacetophenone. They reported that the microfluidic method is able to

access extraction kinetics for particle-laden systems. As the micro-

channels are closed systems, there is greater potential for recycling of

volatile liquids and reduced human exposure to potentially hazardous

chemicals. Darekar et al. [6] studied single-stage solvent extraction of

nitric acid using tri-butyl phosphate (TBP) in dodecane in microbore

tubes. The experiments showed that the configuration of microbore

tube is efficient in the extraction of the solute. Kriel et al. [7] studied

the degree of extraction integrating scrubbing and stripping process in

the channel based microfluidic solvent extraction chips using a sec-

ondary amine as the extractant. They reported the real time-efficiency

of the phase disengagement. Tsaoulidis and Angeli [8] studied the effect

of channel size on the mass transfer characteristics of liquid-liquid plug

flow for capillaries with an internal diameter ranging from 0.5 to 2 mm.

The extraction of {UO2}2+

ions from nitric acid solutions into tri-butyl

phosphate – ionic liquid mixtures, relevant to spent nuclear fuel re-

processing, was studied at different residence times, dispersed phase

fractions, and mixture velocities. They reported that extraction effi-

ciencies dependent on channel size. The packed column is widely used

in oil purification and recovery in oil industries, as well as a small sand-

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2018.02.011

Received 30 October 2017; Received in revised form 16 January 2018; Accepted 10 February 2018

⁎

Corresponding author.

E-mail address: skmaju@iitg.ernet.in (S.K. Majumder).

URL: http://www.iitg.ernet.in/chemeng/skm/home (S.K. Majumder).

Experimental Thermal and Fluid Science 94 (2018) 215–230

Available online 12 February 2018

0894-1777/ © 2018 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

T](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-s2-180228185958/75/1-s2-0-s0894177718301973-main-1-2048.jpg)

![packed column is also used in the laboratories [9–10]. Varteressian and

Fenske [11] studied the liquid-liquid extraction performance in a

packed column. Later on, Moorhead and Himmelblau [12] optimized

the operating condition of a packed liquid-liquid extraction column.

These study motivated researchers to study in depth regarding hy-

drodynamics and mass transfer in extraction process even in channel

based extractor in recent years. Millichannel has the potential to

overcome the shortcomings associated with large-scale equipment

through the reduction of analyte and reagent volumes. Millichannels

are also amenable to gentle and high throughput cell handling.

Incorporation of curvature into the rectangular channel specifies the

importance of Dean flow inside the noncircular ducts [13] causing the

high efficiency of mixing resulting higher mass transfer. Another way to

enhance the transport processes is the incorporation of packing mate-

rials inside the rectangular curved ducts.

Pressure drop is one of the most important design parameter for

designing heat and mass transfer equipments, especially in channel

based equipments for process intensification. Rectangular channels

provide higher pressure drop facilitating higher molecular transport

processes as well as low fabrication cost over conventional circular

channels. The knowledge of pressure drop gives the pattern of energy

dissipation, helps in modeling the system, and forms the basis of as-

sessment of the performance of the equipments. Pressure drop calcu-

lation for the fluid flows through the channel is required to install an

appropriate pump for pumping the fluids. Inside the flow systems, the

mixing of multiphase is mostly depended on the pressure drop of the

system. Therefore the comprehensive understanding of pressure drop

during liquid-liquid flows through millichannel is of considerable

practical importance.

There are several models available to interpret the multiphase flow

system in pipes and channels. Lockhart and Martinelli [14] proposed

separated flow model for air-water two-phase flow through circular

Nomenclature

List of symbols

A cross sectional area of the channel (m2

)

Ac aspect ratio of the channel = ( )w

h

(–)

a,b,c rational number (–)

C Chisholm constant (–)

Ca Capillary number =( )μU

σ

(–)

De Dean number ⎛

⎝

= ⎞

⎠

d Uρ

μ

d

r2

H H

c

(–)

dH hydraulic diameter (m)

dpor dp,eff effective particle diameter (m)

Eu Euler number (–)

′Eu modified Euler number (–)

f’ Fanning friction factor (–)

Fr Froude number ⎛

⎝

= ⎞

⎠

U

gdH

(–)

G mass flux (kg/m2

-s)

g gravity of acceleration (m/s2

)

h height of the channel (m)

j volumetric flux (m3

/s-m2

)

K contraction or expansion coefficient (–)

k roughness of the channel wall (–)

L length of the channel (m)

∗Lo Laplace constant ⎛

⎝

= ⎞

⎠−( ) d/

σ

g ρ ρ H( )

0.5

m

w o

(–)

M molecular weight of the liquid (kg/mol)

n total number of variables (–)

nw total number of moles of water (mol)

n0 total number of moles of organic (mol)

nL number of moles of water in liquid phase (mol)

ns number of moles of water at surface (mol)

nv number of moles of water in vapor phase (mol)

ΔP Density difference of the two-fluids (kg/m3

)

ΔPa accelerating pressure drop (N/m2

)

ΔPf frictional pressure drop (N/m2

)

ΔPg gravitational pressure loss (N/m2

)

ΔPinlet sum of inlet pressure losses (N/m2

)

ΔPT total pressure drop for flow (N/m2

)

Q volumetric flow rate of the liquid (m3

/s)

rc radius of curvature (m)

Re Reynolds number =( )d Uρ

μ

H

(–)

RU relative uncertainties (–)

SD standard deviation (–)

SU standard uncertainties (–)

U actual velocity (m/s)

VB total volume of the bed (m3

)

Vp volume of the pores (m3

)

Vtot total volume of the liquid-liquid mixture (m3

)

vs superficial velocity (m/s)

w width of the channel (m)

We Weber number = =( )CaRe

d ρU

σ

H

2

(–)

We’ modified Weber number ⎛

⎝

= = ⎞

⎠

DeCa

d ρU

σ

d

r2

H H

c

2

(–)

x mixture mass quality (–)

xw liquid phase mole fraction of water (–)

xo liquid phase mole fraction of organic (–)

xi ith component of variables (–)

x mean value of the components (–)

X Martinelli parameter (–)

yw interphase mole fraction of water (–)

yo interphase mole fraction of organic (–)

zw vapor phase mole fraction of water (–)

zo vapor phase mole fraction of organic (–)

Greek symbols

ρ density (kg/m3

)

µ viscosity (N-s/m2

)

σ surface tension (N/m)

ζ entrance loss coefficient (–)

ɛ or εeff effective porosity (–)

ɛtotal total porosity (–)

α volume fraction (–)

ϕ two-phase friction multiplier (–)

ϕs sphericity of the packing material (–)

λ correlation coefficient (–)

Subscripts

C curved channel

m multiphase flow through unpacked channel

m,p multiphase flow through packed channel

o organic phase

S straight channel

s single phase flow through unpacked channel

s,o single phase organic

s,p single phase flow through packed channel

s,w single phase water

w water or liquid or aqueous phase

g gas or air or vapor phase

S. Mondal, S.K. Majumder Experimental Thermal and Fluid Science 94 (2018) 215–230

216](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-s2-180228185958/85/1-s2-0-s0894177718301973-main-2-320.jpg)

![tubes in a horizontal orientation and incorporated the concept of dif-

ferent two-phase friction multipliers. Chisholm [15] expressed the two-

phase friction multipliers as a function of Lockhart-Martinelli para-

meter (X) and the Chisholm parameter (C). Many researchers conducted

the two-phase flow experiments through rectangular channels and tried

to develop the correlations for Chisholm parameter (C) and two-phase

friction multipliers to interpret the frictional pressure drop. Moriyama

et al. [16] proposed a correlation for Chisholm parameter (C) for R113-

N2 flow in a horizontal rectangular duct of hydraulic radius (dH) of

0.014–0.195 mm. Mishima et al. [17] developed a correlation for ‘C’

using air-water two-phase flow through a vertical rectangular duct of

hydraulic diameter ranges from 2.08 to 8.89 mm. Mishima and Hibiki

[18] studied the flow regime, void fraction, rise velocity of slug bubbles

and measured the pressure loss for air-water two-phase flow through

capillary tubes of inner diameter ranges from 1.0 to 4.0 mm. They

proposed correlation for the prediction of ‘C’ values which is applicable

for the flow through vertical and horizontal round tubes as well as

rectangular ducts. Lee and Lee [19], Lee and Mudawar [20] also sug-

gested the correlation for the determination of ‘C’ for the flow of air-

water and water-R134a through a rectangular duct of hydraulic radius

0.78–6.67 mm and 0.349 mm respectively. Rectangular channel and

tubes of hydraulic radius 0.506–12 mm in a horizontal position were

used by Sun and Mishima [21] to investigate the hydrodynamics. They

proposed another correlation for ‘C’ using air-water, refrigerant-CO2

based on their experimental results. Zhang et al. [22] modified the

correlation of Mishima and Hibiki [18] for gas-liquid flow systems.

Tran et al. [23] experimented for the flow of R- 134a, R-12, and R-113,

through a horizontal rectangular duct of the hydraulic diameter of

2.397 mm and incorporated the expression of two-phase friction mul-

tiplier as per Lockhart-Martinelli concept. Followed by the same way in

2012, Qin et al. [24] also suggested a correlation for water-steam sys-

tems but for a rectangular vertical channel of hydraulic radius 3.81 mm.

Chen et al. [25] introduced two different correlations for laminar and

turbulent flow regions for the flow of air-water systems through a

horizontal rectangular channel of hydraulic diameter 3–4.5 mm.

Blasius [26] proposed a friction factor relation with Reynolds

number for fully developed turbulent flow through the circular tubes as

well as rectangular channels. Shah and London [27], Harnett and Kostic

[28], Abdelall et al. [29], Hrnjak and Tu [30] used the same relation to

determine the friction factors for laminar flow through rectangular

channels. The friction factor for both developing and developed flow

regimes through rectangular microchannel was categorized by Phillips

[31]. Churchill [32] in 1977 developed a friction factor correlation for

flow through the rectangular channel. In 2017, Li and Hibiki [33] used

the same correlation developed by Churchill [32] for both laminar and

turbulent flow through a rectangular channel. Flows through curved

microchannel were investigated by Hua and Yang [34], Wang and Liu

[35]. They [34,35] developed the pressure drop and friction factor re-

lationship as a function of Reynolds number and Dean number.

Pressure drop correlation for the flow through packed bed was first

developed by Ergun [36,37] in the year 1952. It was the combination of

Kozeny–Carman equation [37], applicable for laminar flow regimes and

Burke-Plummer equation [37], applicable for turbulent flow regimes.

Therefore, the Ergun equation is valid for a wide range of flow condi-

tions through the packed bed. Later on, many investigators (Feng [38],

Foumeny et al. [39], Eisfeld et al. [40], Montillet et al. [41]) were tried

to modify the Ergun equation according to geometry and application of

packed unit.

From the literature, it is observed that very less attention has been

given to the rectangular serpentine channels in both micro and macro

domain. Most of the experiments have been carried out using air-water

systems even though they used the rectangular curved channel. To the

best of our knowledge, no experiment has been carried out to in-

vestigate the pressure drop of liquid-liquid flow through rectangular

serpentine channels in both packed and unpacked conditions. Liquid-

liquid flow has potential application in the mass transfer like extraction

in micro and millichannel for process intensifications. The present study

aims to investigate the effect of operating variables on the pressure drop

and friction factor for the liquid-liquid flow through rectangular ser-

pentine millichannel with and without packing and the development of

general empirical models to interpret the results based on experimental

results. In industries, it would be the new beginning of the introduction

of the rectangular serpentine packed bed for the process intensification

for physical and reactive mass transfer.

2. Theoretical background

Frictional pressure drop for multiphase phase liquid flow can be

expressed as

= − − −P P P P PΔ Δ Δ Δ Δf T a g inlet (1)

where ΔPf is the multiphase frictional pressure drop, ΔPT is the total

pressure drop, ΔPa is the pressure drop due to the acceleration of fluid

velocity, ΔPg is the gravitational pressure drop. In the present study, the

ΔPa term of Eq. (1) is nullified as the inlet and outlet velocities are

considered to be the same. ΔPinlet is the sum of contraction or expansion

and entrance loss at the inlet which can be expressed as

= +P K ζ

ρU

Δ ( )

2

inlet

2

(2)

where ρ is the density of the fluid, U is the actual velocity of the fluid at

the contraction or expansion zone, K is the contraction or expansion

coefficient which is assumed to be equal to 0.5 and ζ is entrance loss

coefficient and holds the value nearly equal to 1.31 [42]. Gravitational

effect on the pressure drop is expressed as Froude number as

=Fr

U

gdH (3)

where g is the gravitational acceleration and dH is the hydraulic dia-

meter. Though the horizontal flow is encountered in the following

context, the density ratio of the two fluids greater than one results in

the slip between the phases which incorporated the effect of Froude

number or gravity or hydraulic jump [43–45,71]. In that case, when the

velocity of the phases increase, a wave is generated at the interphase of

the two fluids and at high velocity the waves break down and form

bubbles or slugs inside the flow field. Surface waves can form under the

influence of gravity even in the absence of air and in the horizontal flow

condition when the densities of the fluids are different. If there is

stratified flow due to density difference the film inversion [72] at the

bends also influences the mixing or formation of bubble and slug in the

channel. At that condition difference in density persists along the ver-

tical line through the channel which demands the effect of gravity or

Froude number. In the present study, the density ratio is 1.154 and the

Froude number for the mixture ranges from 0.99 to 5.18 makes the

incorporation of Froude number in case of mixed phase flow sig-

nificantly. The Froude number ranges for the hydraulic jumps for air-

water flows are [46]:1 < Fr < 2.5 for weak jump, 2.5 < Fr < 4.5

for oscillating jump, 4.5 < Fr < 9 for steady jump and Fr > 9 for

strong jump. The liquid densimetric Froude number is given by the Eq.

(4) as [47]

⎜ ⎟= ⎛

⎝

⎞

⎠

Fr

ρ

ρgd

U

Δ

d

s

H

s

0.5

(4)

The hydraulic jump is also observed in single-phase flow in la-

boratory channels [47,73]. In the present study, the Froude number for

the single-phase flow ranges from 0.39 to 3.02, which also implies an

effect on the fluid flow. In oil and gas station Froude number is kept

always less than 0.30 using submerged outlets to avoid air entrainment

and ensure undistributed flow without pulsations. The present study

uses an air open outlet where entrainment might causes hydraulic jump

and accounts higher Froude number. Moreover, there might be the

S. Mondal, S.K. Majumder Experimental Thermal and Fluid Science 94 (2018) 215–230

217](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-s2-180228185958/85/1-s2-0-s0894177718301973-main-3-320.jpg)

![release of dissolved gas or vapor of its own or some air pocket at the

joining of the pressure sensors. As a result, the Froude number is sig-

nificant in both single and mixed phase flows. Depending on the above

effects various types of flow patterns are observed in the liquid-liquid

two-phase flows through the rectangular channels [48–50]. Hydraulic

diameter of the rectangular channel was calculated as

=

+

d

wh

w h

2

( )

H

(5)

where w and h are the width and height of the rectangular channel

respectively. The calculations were done based on the actual velocities

of the phases depending on the flow distribution inside the channel.

Actual velocities are calculated from the volume fraction of each phase

inside the channel by measuring the volumetric flow rate of each phase.

The friction factor is a dimensionless representation of the viscous

pressure drop due to the effect of the fluid's viscosity near the surface of

the channel. As per Fanning equation, the Fanning friction factor can be

represented by

′ =f

d P

ρU L

Δ

2

H f

2

(6)

In the case of the packed bed, U is replaced byU ε/ eff . The term, εeff is

the porosity of the packed channel. From, the experimental results, it

was observed that with changing velocities of the phases, the pressure

drop changes. Therefore, the pressure drop mainly depends on

Reynolds number (Re). In the case of a rectangular curved channel, the

radius of curvature affects the flow creating Dean effect. As a result

Dean number (De) replaces the Reynolds number (Re) for the flow

through the rectangular curved channel. Friction factor depends on

another two significant dimensionless numbers [67] such as capillary

number (Ca) for milli- and micro-channel and Froude number (Fr) for

mainly the fluids of different densities. According to viscous-capillary

paradox, an apparent contradiction, the structure of Darcy's law is that

of a viscous law but typical capillary numbers of 10−6

– 10−3

indicate a

capillary dominated behavior [51]. In the visco-inertia regime, capil-

lary number is higher than 10−3

. When one studies a multi-phase flow

system, the calculation of the capillary number is very much important

to understand the factors that are affecting the flow behavior. The

critical value of the capillary number depends on the geometry of the

packing material and other fluid properties. The internal circulation

within the slugs may arise depending on the physical properties of the

fluids and the prevalent operating conditions [52,53]. Capillary pres-

sure acts as both the opposing and driving force for fluid transport. The

phases, water and toluene used in the present study are wetting with

the channel wall and the sand particles. So, there must be some capil-

lary pressure due to the wetting characteristics. The Dean number,

capillary number, Froude number and friction factor for single and

multi-phase flows through the unpacked channel are represented as

follows:

Dean number for the single phase is defined as

=De

d

r

Re

2

s s

H

c (7)

where

=

d ρ U

μ

Res

H s s

s (8)

=Ca

μ U

σ

s

s s

s (9)

=Fr

U

gd

s

s

H (10)

and

′ =f

d

ρ U

P

L2

Δ

s

H

s s

f

2

(11)

Dean number for the mixture phase is defined as

=De

d

r

Re

2

m m

H

c (12)

where

=

d ρ U

μ

Rem

H m m

m (13)

=Ca

μ U

σ

m

m m

m (14)

=Fr

U

gd

m

m

H (15)

= +U U α U α/ /m s o o s w w, , (16)

and

′ =f

d

ρ U

P

L2

Δ

m

H

m m

f

2

(17)

where the subscripts ‘s’ represents the single-phase flow and ‘m’ re-

presents the multi-phase mixture flow. Hydraulic diameter (dH) is re-

presented by the Eq. (5). Similarly, the three dimensionless numbers

and the friction factor for the packed channel are calculated using the

following relations:

Dean number for the single phase flow through packed channel is

defined as

=De

d

r

Re

2

s p s p

H

c

, ,

(18)

where

=

d ρ U ε

μ

Re

( / )

s p

p s s eff

s

,

(19)

=Ca

μ U ε

σ

( / )

s p

s s eff

s

,

(20)

=Fr

U ε

gd

( / )

s P

s eff

p

,

(21)

and

′ =f

d

ρ U ε

P

L

( )

2 ( / )

(Δ )

s p

p

s s eff

f p

2

(22)

Dean number for mixture flow through packed channel is defined as

=De

d

r

Re

2

m p m p

H

c

, ,

(23)

where

=

d ρ U ε

μ

Re

( / )

m p

p m m eff

m

,

(24)

=Ca

μ U ε

σ

( / )

m p

m m eff

m

,

(25)

=Fr

U ε

gd

( / )

m p

m eff

p

,

(26)

= +U U ε α U ε α( / / )m p s o eff o s w eff w, , , (27)

and

S. Mondal, S.K. Majumder Experimental Thermal and Fluid Science 94 (2018) 215–230

218](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-s2-180228185958/85/1-s2-0-s0894177718301973-main-4-320.jpg)

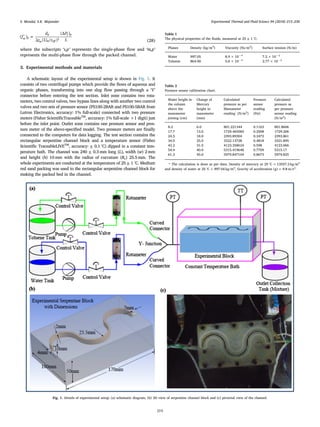

![The physical properties of the systems measured at 25 ± 1 °C are

shown in Table 1. The dimensions of the serpentine channel block are

shown in schematic diagram (Fig. 1). The pressure sensors and the

temperature sensor are calibrated before the main experiment. The

pressure sensors are calibrated with the help of a mercury manometer

in which one side of the manometer was kept open to air. A graduated

cylindrical column of height 1.5 m is connected to the pressure sensor

and the manometer at the same height from the datum. The column is

filled with water at a certain level and set the pressure sensor reading as

zero as per manometer initial reading. When the water height of the

column is increased the change in manometer as well as pressure sensor

reading are noted down. The noted data of the pressure sensor and the

manometer with respect to water height are shown in Table 2. The

pressure sensor calibration curve is represented in Fig. 2(a). The tem-

perature sensor is calibrated with the help of a high accuracy calibrated

handheld thermometer (TTI-10, Isotech, accuracy = ± 0.01 °C). Both

the temperature sensor (accuracy =± 0.1 °C) and the thermometer are

dipped in a constant temperature water bath. The recorded data are

shown in Table 3 and the calibration curve is represented in Fig. 2(b).

The densities, viscosities and surface tensions are measured by specific

gravity bottle (ATICO Medical Pvt. Ltd., AM-90024, 100 ml), rheometer

(Anton Paar, Physica MCR-301) and tensiometer (Kyowa Interface

Science, DY-300) respectively. Finally, the volumetric flow rate of the

two fluid mixtures is measured by collecting the sample for a particular

time by measuring cylinder and a stopwatch. The volumetric flow rates

are controlled and measured by the valves and the rotameters by

changing one keeping the other fixed and vice versa. Average pressure

drop for a particular mixture flow rate is noted by averaging 200 data

points measured using pressure sensor at each flow rate. The volume

fraction of each phase in the channel is calculated from the total mixed

phase volumetric flow rate and the volumetric flow rate of a single

phase for a particular set of flow condition.

The mixture properties of the fluids are calculated from the fol-

lowing equations

= +ρ ρ α ρ αm w w o o (29)

where ρm, ρw and ρo are densities of the mixture, aqueous phase (water)

and the organic phase (toluene) respectively. The symbols αw and αo

denote the volume fractions of aqueous phase and organic phase re-

spectively. According to Olimans [54] viscosity of the mixture is cal-

culated by

= +μ μ α μ αm w w o o (30)

where μm, μw and μo are viscosities of the mixture, aqueous phase and

organic phase respectively.

The surface tension of the liquid-liquid mixture: The liquid mixture

of two components, water and organic liquid (toluene), is assumed to be

in equilibrium with its own vapor. The liquid-vapor interface is treated

here in the manner of Bakker [55], Verschaffelt [56] and Guggenheim

[57] as a thin phase separated from the bulk liquid and vapor by two

dividing surfaces which enclose the region of property variation normal

to the interface (Eberhart, 1966 [58]).

The bulk liquid phase is assumed to have mole fractions xw for water

and xo for organic liquid (toluene), while the bulk vapor phase has mole

fractions zw and zo for water and organic liquid respectively. Although

the interfacial or surface phase has a composition which varies in a

direction normal to the dividing surfaces, it is assigned overall mole

fractions yw and yo for water and organic liquid respectively which

satisfy the material balance conditions for the system. For component

water in the mixture, for example, this condition is nw = nLxw + nsyw +

nvzw where nw is the total number of moles of water in the three

“phases,” of the mixture and nL, ns, and nv are the number of moles of

water and toluene in the liquid, surface, and vapor phases, respectively.

Since, in general, ns and nv are very much smaller than nL, it will be

assumed that xw is essentially equal to the overall mole fraction of

water, nw/(nw + n0). The surface tension of liquid mixture, σm, is then

assumed to be a linear function of the surface layer mole fraction which

is expressed as (Eberhart, 1966 [58]). In the present study, we are

considering the liquid-liquid surface tension separately with its in-

dividual liquid vapour. Based on the individual surface tension of the

liquid with its vapour, the surface tension of the liquid-liquid mixture is

calculated according to Eq. (31).

= +

= ++ +

σ y σ y σ

σ σ

m w w o o

α V ρ M

α V ρ M α V ρ M w

α V ρ M

α V ρ M α V ρ M o

( ) /

( ) / ( ) /

( ) /

( ) / ( ) /

w tot w w

w tot w w o tot o o

o tot o o

w tot w w o tot o o (31)

where σm, σw and σo are surface tensions of the mixture, aqueous phase

and organic phase respectively. Vtot is the total volume of the liquid-

liquid mixture, M is the molecular weight of the liquid.

The average particle diameter (dp,eff), effective porosity of the

packed bed (εeff) and sphericity of the packing material (ϕp) are the

three important parameters to govern the hydrodynamics in the packed

bed. The average particle diameter is determined by sieving method. In

(a)

0 1 2 3 4 5 6

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

PS×10

-3

(N/m

2

)

PM × 10

-3

(N/m

2

)

PS = 0.99991PM + 0.0002391

(b)

20 25 30 35 40 45 50 55 60 65

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

55

60

65

Ts(

o

C)

TTTI-10 thermometer (

o

C)

Ts

= 0.99951 TTTI-10

+ 0.02237

Fig. 2. Pressure and Temperature sensor calibration: (a) Pressure sensor calibration plot (b) Temperature sensor calibration plot.

Table 3

Temperature sensor calibration chart.

TTTI-10 high accuracy handheld thermometer

reading (°C)

Temperature sensor reading

(°C)

22.305 22.31

24.481 24.50

25.001 25.01

26.203 26.22

30.402 30.41

40.142 40.13

50.121 50.12

60.042 60.04

S. Mondal, S.K. Majumder Experimental Thermal and Fluid Science 94 (2018) 215–230

220](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-s2-180228185958/85/1-s2-0-s0894177718301973-main-6-320.jpg)

![this method, a series of sieve set has been used and the particles are

screened by the sieve of sizes ASTM No. 35 and 40 (U.S. Standard).

Based on the average particle diameter according to the literature [68],

the sand is classified as medium sand. The average particle size as per

present experiment is 462 µm. The effective porosity is calculated by

using the Eq. (32) [69].

=ε

V

V

eff

p

B (32)

where Vp is the volume of the pores and VB is the total volume of the

bed. According to Zou and Yu [59] for dH/dp > 3.95, the effective

porosity εeff is defined as

= + −ε e0.372 0.002( 1)eff

d d15.306 /p H

(33)

The effective porosity (εeff) of a packed bed can also be calculated by

the correlation (Eq. (34)) developed by Klerk [60] which is valid in the

range of 2 ≤ dH/dp ≤ 19. The correlation can be expressed as

⎜ ⎟= + ⎛

⎝

− ⎞

⎠

ε

d

d

0.373 0.917exp 0.824eff

H

p (34)

The effective porosity estimated experimentally in the present work

is 0.36 which is within 6% error based on the predicted value calculated

by the equation (33) and (34). The experimental determination of the

effective porosity is done by dividing the pore volume with the total

volume of the channel. From the literature, it is seen that the porosity

range of the medium sand is 0.22–0.49 [61,62,68,70]. Therefore the

present experimental data of porosity is justified for the sand particle

taken for the experiment. The third and another important parameter

for packed bed is sphericity of the packing materials. The sphericity is

calculated by using the modified procedure of Krumbein and Sloss [63].

It is defined as the ratio of the diameter of the largest drawn circle

possible inside the particle (rp) to the diameter of the smallest drawn

circle surrounding the particle (rc) as shown in Fig. 3(a). A typical

snapshot of the sand particle taken by Sony DSC-H400 Point and Shoot

Camera is shown in Fig. 3(b). It is analyzed by Digimizer®4 software.

The mathematical form of sphericity of particle is expressed as

=ϕ

r

rp

c

p (35)

From the analysis, it is found that the sphericity of particle is 0.80,

which is within the range 0.50–0.90 for natural sands reported by Cho

et al. [64]. The volume fraction of each phase inside the channel was

measured by volumetric flow rate measurement process using a mea-

suring cylinder (Borosil, 100 ml, Tolerance ± 0.5 ml) and a stopwatch

(Seiko digital stopwatch Cal. S056, Accuracy ± 0.0012%).

The percentage error of the experimental and calculated values are

determined by

⎜ ⎟= ⎛

⎝

− ⎞

⎠

×%Error

Experimental Calculated

Experimental

100%

(36)

Finally, the deviation of experimental results from the available

correlations and newly generated correlations are analyzed by root

mean square deviation (RMSD) and mean deviation (MD) which are

defined respectively as

∑ ⎜ ⎟=

⎛

⎝

⎜

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎛

⎝

− ⎞

⎠

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎞

⎠

⎟ ×RMSD

N

1 (Experimental Calculated)

Experimental

100%

2 0.5

(37)

∑⎜ ⎟= ⎛

⎝

− ⎞

⎠

×MD

N

1 (Experimental Calculated)

Experimental

100%

(38)

3.1. Uncertainty analysis of experimental data

In the present work each experiment is repeated at least ten times

and then the average value of the results are taken. The standard de-

viation (SD), standard uncertainties (SU) and percentage relative un-

certainties (RU) of the repeated experiments are calculated by Eq. (39),

Eqs. (40) and (42) respectively [65].

∑

=

−

−

=

SD

x x

n

( )

1

i

N

i

1

2

(39)

=S

SD

n

U

(40)

where xi is the ith component of variables and n is the total number of

variables. x represents the mean value and mathematically it is ex-

pressed as

∑=

=

x

n

x

1

i

N

i

1 (41)

= ×R

S

x

100%U

U

(42)

The ranges of mean, standard deviation and uncertainty of the ex-

perimental results of total volumetric flow rate and frictional pressure

drop for both packed and unpacked channel are shown in Table 4.

Fig. 3. Measurement of sphericity of packing materials: (a) schematic representation of sphericity and (b) typical pictorial analysis of particle by image analysis software.

S. Mondal, S.K. Majumder Experimental Thermal and Fluid Science 94 (2018) 215–230

221](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-s2-180228185958/85/1-s2-0-s0894177718301973-main-7-320.jpg)

![4. Results and discussion

4.1. Variations of frictional pressure drop and friction factor with operating

variables

Frictional pressure drop depends on flow velocity. Flow velocity is

directly influenced by the Reynolds number. Reynolds number in-

creases with increasing flow velocity. Dean number is considered to

interpret the hydrodynamics in case of flow through the serpentine

channel as the curvature effects generate secondary flow [13]. Capillary

number influences the flow when the channel becomes milli or micro in

size. In case of two-phase flow, when the densities of the two phases are

different, the gravity also affects the flow. The variations of pressure

drop per unit length of the channel with the above three dimensionless

numbers are shown in Fig. 4(a) and (b) for single and multiphase flows

respectively.

Frictional pressure drop per unit length increases with increasing

Dean number, capillary number as well as Froude number [67] for both

single and multiphase flow (Fig. 4(a), (b)). In both the figures, Dean

number curve is steeper than the others which confirm the higher effect

on frictional pressure drop with increasing the velocity of the phases.

According to the experimental result, Froude number effect is more

pronounced in the case of multiphase flow than single phase flow due to

the density difference between the two fluids. As the Dean number has

the higher contribution to frictional pressure drop, its influence on the

friction factor prevails accordingly as shown in Fig. 5(a) and (b).

The friction factor decreases exponentially with increasing Dean

number [Fig. 5(a) and (b)]. Friction factor value for the multiphase flow

is lower than the single phase flow as the Dean number is higher for the

multiphase system. In case of the packed channel also the Dean number

has the significant effect on pressure drop as well as friction factor.

Along with the Dean number, capillary number and Froude number

effects are significant on the frictional pressure drop for the flow

through the packed channel as shown in Fig. 6(a) and (b).

As the Dean number has the higher impact on the pressure drop, it

demands valuable impression on friction factor. The friction factor

variation with the Dean number for the flow through the packed

channel is shown in Fig. 7(a) and (b).

Figs. 6 and 7 shows the higher values of the pressure drop and

friction factor for the packed channel than those in the unpacked

channel (Figs. 4 and 5).

4.2. Analysis by model

There is no reliable theoretical model available to predict the

pressure drop as well as friction factor for the water or organic single

phase and water-toluene multiphase flow through the rectangular

packed and unpacked serpentine horizontal channel. In the present

study, an attempt has been made to predict the pressure drop and

friction factor by developing empirical correlations.

4.2.1. Analysis by empirical models for flow through unpacked channel

Pressure drop generally depends on different operating variables:

hydraulic diameter, the radius of curvature, liquid superficial or actual

velocity (U), the density of the liquid, the viscosity of the liquid, the

surface tension of the liquid. The experimental data have been analyzed

to develop the correlation for pressure drop as a function of the oper-

ating variables as:for single phase flow,

⎜ ⎟

⎛

⎝

⎞

⎠

=

P

L

f d r U ρ μ σ g

Δ

( , , , , , , )

f

s

H c s s s s

(43)

For mixture flow,

⎜ ⎟

⎛

⎝

⎞

⎠

=

P

L

f d r U ρ μ σ g

Δ

( , , , , , , )

f

m

H c m m m m

(44)

The subscripts ‘s’ denotes single-phase flow whereas ‘m’ denotes the

mixture flow of phases. The functionality of pressure drop obtained by

dimensional analysis (Buckingham Pi theorem) in terms of various

significant dimensionless groups which can be expressed as

′ = = =Eu Eu

d

L

P

ρU

d

L

λDe Ca Fr

ΔH f H a b c

2

(45)

where Eu' is the modified Euler number. The Euler number (Eu) is

signified by the ratio of pressure forces to inertial forces. The parameter

λ is a coefficient and ‘a’, ‘b’, and ‘c’ is the rational numbers. The

Table 4

Uncertainties to the experimentally measured quantities.

Properties and measurements Mean No. of run Standard Deviation × 102

Standard uncertainty × 102

% relative uncertainties

Total volumetric flow rate × 106

(m3

/s) [without packing] 0.89 – 5.43 10 0.037 – 0.24 0.012 – 0.075 0.013 – 0.014

Total volumetric flow rate × 106

(m3

/s) [with packing] 0.30 – 1.52 10 0.038 – 0.23 0.012 – 0.074 0.04 – 0.05

Pressure drop per unit length × 104

(N/m3

) [without packing] 3.51 – 9.28 10 0.032 – 0.038 0.010 – 0.012 0.0013 – 0.003

Pressure drop per unit length × 105

(N/m3

) [with packing] 4.09 – 9.68 10 0.033 – 0.040 0.010 – 0.013 0.0013 – 0.002

(a)

0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800

2

3

4

5

6

7

Des

Cas

×10

5

Frs

×10

3

(ΔPf

/L)s

×10

-3

-experimental(N/m

3

)

Des

,Cas

,Frs

(-)

(b)

0 1000 2000 3000 4000 5000

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

Dem

Cam

×10

5

Frm

×10

3

(ΔPf

/L)m

×10

-3

-experimental(N/m

3

)

Cam

, Frm

, Dem

(-)

Fig. 4. Variation of frictional pressure drop with the dimensionless numbers in unpacked channel: (a) single phase flow and (b) multiphase flow.

S. Mondal, S.K. Majumder Experimental Thermal and Fluid Science 94 (2018) 215–230

222](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-s2-180228185958/85/1-s2-0-s0894177718301973-main-8-320.jpg)

![The correlation coefficients and the standard errors are found to be

0.999 and 0.035 for Eq. (46), 0.999 and 0.024 for Eq. (47). The Eq. (46)

and Eq. (47) fit the experimental data with maximum 4.6% (Fig. 11(a))

and 5.0% (Fig. 11(b)) error respectively. From Eqs. (46) and (47), it is

obvious that the pressure drop for single and multiphase flow depends

on three significant dimensionless numbers such as Dean number De( ),

capillary number Ca( ) and Froude number Fr( ).

4.2.2. Analysis by Lockhart-Martinelli model

Lockhart-Martinelli [14], first introduced the pressure drop model

for the two-phase flow through the circular channel. The basics of the

model are that the two-phase frictional pressure drop is a multiplier of

any single phase frictional pressure drop. The multiplier is called

pressure drop multiplier which is denoted by ϕw

2

. According to their

model,

=P L ϕ P L(Δ / ) (Δ / )f m w f w

2

(48)

The pressure drop multiplier is related to the Lochart-Martinelli’s

parameter [14] as:

= + +ϕ

C

X X

1

1

w

2

2 (48a)

= + +ϕ CX X1o

2 2

(48b)

where C is called Chisholm’s [15] constant. The parameter X is called

Lockhart-Martinelli’s parameter which is defined as for aqueous-or-

ganic mixture

= ⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

X

P L

P L

(Δ / )

(Δ / )

f w

f o

0.5

(49)

Based on the present experimental results, the correlations for ′ ′ϕw

2

and C are developed incorporating the different operating variables

which are represented as follows:

= = ′ϕ De Ca We7.594( ) 7.594( )w w w w

2 0.0398 0.0398

(50)

where ′Wew is the modified Weber number which is defined as

⎜ ⎟′ = = ⎛

⎝

⎞

⎠

We De Ca

d

r

Ca( ) Re

2

w w w w

H

c

w

(51)

and

=C De Ca4.92( )w w w

0.07912

(52)

The ranges of operating variables for the correlations [Eqs. (50) and

(52)] are < <De77.77 441.21w and × < < ×− −Ca1.01 10 5.713 10w

3 3.

The correlation satisfies the experimental data with maximum 4.7%

error with the mean deviation of 2.51. The variations of ϕw

2

and C with

the dimensionless numbers are shown in Fig. 8(a) and (b).

The predicted values from the correlations are close enough to the

experimental values. Predicted values from the present correlation are

plotted against the experimental values and represented in the Fig. 9(a)

and (b). The pressure drop data obtained from the present study were

also compared with the previous models as shown in Table 5.

The mean and root mean square deviation of the experimental

(a)

100 200 300 400 500 600

6.6

6.8

7.0

7.2

7.4

7.6

7.8

8.0

Dew

Caw

×10

5

----- Correlation (Eq. (50))

φ

2

w

(−)

Dew

,Caw

(-)

(b)

100 200 300 400 500

3.8

4.0

4.2

4.4

4.6

4.8

5.0

5.2

Dew

Caw

×10

5

---- Correlation (Eq. (52))

Cw

(-)

Dew

, Caw

(-)

Fig. 8. Variation of pressure drop parameters with dimensionless numbers in unpacked channel: (a) pressure drop multiplier and (b) Chisholm’s constant.

(a)

6.0 6.5 7.0 7.5 8.0 8.5

6.0

6.5

7.0

7.5

8.0

8.5

+3.87%

-3.68%

φw

2

-predicted(-)

φw

2

- experimental (-)

(b)

3.0 3.5 4.0 4.5 5.0 5.5 6.0

3.0

3.5

4.0

4.5

5.0

5.5

6.0

-2.58%

+4.65%

Cw

-predicted(-)

Cw

- experimental (-)

Fig. 9. Experimental and predicted value comparison: (a) Lockhart-Martinelli parameter and (b) Chisholm constant.

S. Mondal, S.K. Majumder Experimental Thermal and Fluid Science 94 (2018) 215–230

224](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-s2-180228185958/85/1-s2-0-s0894177718301973-main-10-320.jpg)

![Table 5

Important pressure drop models and correlations for unpacked channel.

Working fluids Correlations Geometry & Orientation Authors & Years

Water, oils,

hydrocarbons

=( ) ( ) ϕ

dP

dz m

dP

dz w

w

2

where = + +ϕ 1w

Cw

X X

2 1

2;

=C 20tt (liquid turbulent and organic turbulent)

=C 12lt (liquid laminar and organic turbulent)

=C 10tl (liquid turbulent and organic laminar)

=C 5ll (liquid laminar and organic laminar)

= ( ) ( )X /

dP

dz w

dP

dz o

, = −( ) f x(1 )

dP

dz w

w

G

dH ρW

O

2 2

2

and =( ) f x

dP

dz O

O

G

dH ρo

o

2 2

2

=fw w

16

Re

for <Re 2000w or = −

f 0.079Rew w

0.25

for >Re 2000w

=fo o

16

Re

for <Re 2000o or = −

f 0.079Reo o

0.25

for >Re 2000o

=

−

Rew

G xo dH

μw

(1 )

and =Reo

GxodH

μo

Mainly circular tubes, Horizontal Lockhart and

Martinelli (1949),

[14]

Gas-liquid and Vapor-

liquid

=( ) ( ) ϕ

dP

dz m

dP

dz w

w

2

,

= + − ⎡

⎣

⎢

− + ⎤

⎦

⎥

− − −

ϕ X Bx x x1 ( 1) (1 )w g

n

g

n

g

n2 2

2

2

2

2

2

where n = 0.2

= ( ) ( )X /

dP

dz W

dP

dz g

2 ;

If < <X0 9.5:

=B

G

55

0.5

for ⩾G 1900 kg/m2

s;

=B

G

2400

for < <G500 1900 kg/m2

s;

=B 4.8for <G 500 kg/m2

s;If < <X9.5 28: =B

YG

520

0.5 for ⩽G 600 kg/m2

s

=B

Y

21

for >G 600 kg/m2

s For >X 28: =B

X G

15,000

2 0.5

Mainly circular pipes, Horizontal Chisholm (1967), [15]

Water-air = − −C e21(1 )dH319

using the Lockhart-Martinelli model

Rectangular duct, dH = 2.08 – 8.89 mm,

Vertical upward

Mishima et al. (1993),

[17]

Refrigerants, R-12

⎜ ⎟= − ⎛

⎝

⎞

⎠

( ) f0.87Re

dp

dz m

eq w

Geqρw

dH

0.12

2

=Re ,eq

GeqdH

μw

>Re 2500eq ; = ⎡

⎣

⎢

− + ⎛

⎝

⎞

⎠

⎤

⎦

⎥

G G x x(1 )eq o o

ρw

ρo

0.5

Rectangular channel, dH = 1.56 – 2.64 mm. Yang and Webb

(1995), [66]

Water-air = − −C d21[1 exp( 0.319 )]H Mainly vertical and horizontal round tube,

also applicable in horizontal rectangular duct.

dH= 1.0 – 4.0 mm.

Mishima and Hibiki

(1996), [18]

R- 134a, R-12, and R-1

13

=( ) ( ) ϕ

dP

dz m

dP

dz w

w

2

with

= + − − +∗ϕ X Lo x x x1 (4.3 1)[ (1 ) ]w o o o

2 2 0.875 0.875 1.75

⎜ ⎟= ⎛

⎝

⎞

⎠

∗

−

Lo

σm

dH g ρw ρo

2 ( )

0.5

and =X

dP dz w

dP dz o

2 ( / )

( / )

Rectangular channel, dH = 2.397 mm,

Horizontal

Tran et al. (1999),

[23]

Water-air =C Aλ ψ Req r

eq

S

using the Lockhart-Martinelli model

=λ

μw

ρwσmdH

2

and =ψ

μwj

σm

Laminar: <Re ,Re 2000w g ; Turbulent: >Re ,Re 2000w g .

Rectangular duct, dH = 0.78 – 6.67 mm,

Horizontal

Lee and Lee (2001),

[19]

Water-R134a For laminar liquid and laminar vapor:

=C We2.16Rew w w

0.047 0.6

For laminar liquid and turbulent vapor:

=C We1.45Rew w w

0.25 0.23

and =Wew

GwdH

ρwσw

2

using the Lockhart-Martinelli model

Rectangular channel, dH = 0.349 mm,

Horizontal

Lee and Mudawar

(2005), [20]

Air-water For laminar flow region:

= − −ϕ A U gd0.2485 { /( ) } Rel c w H w

0.355 0.5 0.233 (3/8)

For turbulent flow region:

= +−

ϕ A U U U0.848 {( )/ } Rel c w g w w

0.145 0.425 (3/8)

Rectangular channel, dH = 3 – 4.5 mm,

Horizontal

Chen et al. (2007),

[25]

(continued on next page)

S. Mondal, S.K. Majumder Experimental Thermal and Fluid Science 94 (2018) 215–230

225](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-s2-180228185958/85/1-s2-0-s0894177718301973-main-11-320.jpg)

![values with predicted values from the available models are tabulated in

Tables 6 and 7. Percentage errors of the models with the experimental

values are also plotted as shown in Fig. 10(a) and (b).

Fig. 10(a) and (b) represent the fact that there is a wide difference

between the experimental data for ϕw

2

and C with the other available

pressure drop equations for flow through the rectangular channel which

is either straight rectangular channel or two-phase flow having one

gaseous in most of the cases. The present study consists totally different

geometries as well as different fluids like water and toluene. In this

context modification of the previous model was done. The calculated ‘

ϕw

2

’ and ‘C’ values of experimental data are compared with the available

correlations (Tables 6 and 7). From Table 6 and Fig. 10(a), it is seen that

Tran et al. model [23] is the best fit with present experimental value for

ϕw

2

. Whereas Sun and Mishima [21], Zhang et al. [22] models show

better fit for coefficient C as shown in Table 7 and Fig. 10(b). As per

newly developed correlation in this work, the present experimental

data is shown better fit with respective errors as shown in Fig. 9(a) and

(b).

The single-phase flow friction factor ( ′fs ) through the unpacked

channel can be obtained by using the Eq. (46). Similarly, the multiphase

flow friction factor ( ′fm) through the unpacked channel can be obtained

by using Eq. (47). Models available for the calculation of friction factor

for both unpacked and packed channel and their deviation from the

present values are tabulated in Table 8–11.

Calculated friction factor values from the present experiment are

compared with the available correlations which are shown in Table 9.

Churchill [32], Li and Hibiki [33] correlations are the better fit with our

present experimental data but error percentage is high enough 91.06

(Table 9).

4.2.3. Pressure drop models for flow through packed channel

Following the similar way of the unpacked channel, the correlations

were generated for the pressure drop for both single and multiphase

flows through the packed rectangular serpentine millichannel. Medium

sand was used as the packing material. The generated correlations are

as follows:

For single phase:

⎜ ⎟

⎛

⎝

⎜

⎞

⎠

⎟

⎛

⎝

⎞

⎠

= ′ = × −

d

ρ U ε

P

L

f De Ca Fr

/

Δ

2( ) 1.94 10 ( ) ( )

p

s s eff

f

s p

s p s p s p s p2 2

,

2

, ,

0.368

,

2.351

(53)

The subscript ‘ s p, ’ represents the single-phase flow through the

packed bed. The correlation coefficient and the standard error of the Eq.

(53) are 0.999 and 0.023. Various parameters for the correlation are

× < < ×( )1.845 10 3.764 10

P

L s p

5 Δ

,

5f

N/m3

; < <De1.77 11.84s p, ;

< <Ca0.00053 0.0035s p, and < <Fr0.387 3.016s p, . Eq. (53) shows the

similarity with the experimental data by maximum error 5.1%

(Fig. 11(a)).

For mixture of two phases:

⎜ ⎟

⎛

⎝

⎜

⎞

⎠

⎟

⎛

⎝

⎞

⎠

= ′ = × −

d

ρ U ε

P

L

f De Ca Fr

/

Δ

2( ) 4.419 10 ( ) ( )

p

m m eff

f

m p

m p m p m p m p2 2

,

1

, ,

0.073

,

1.694

(54)

The subscript ‘ m p, ’ represents the multiphase flow through the

packed bed. The correlation coefficient and the standard error of the Eq.

(54) are 0.999 and 0.025 respectively. The ranges of operating variables

for the correlation are × < < ×( )4.063 10 9.644 10

P

L m p

5 Δ

,

5f

N/m3

;

< <De9.866 59.697m p, ; < <Ca0.0026 0.0151m p, and <2.548

<Fr 16.640m p, . Eq. (54) shows the similarity with the experimental data

by maximum error 5.3% (Fig. 11(b)). The comparison of the

Table 5 (continued)

Working fluids Correlations Geometry & Orientation Authors & Years

Air–water, refrigerants,

CO2

For Rew < 2000 and Reg < 2000:

=( ) ( )ϕ

dp

dz m

w

dp

dz w

2

; = + +ϕ 1w

Cw

X

Cw

X

2

2 ;

= +

⎡

⎣

⎢ −

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎛

⎝

−

+ ∗

⎞

⎠( )C e26 1 1w

w Lo

Re

1000

0.153

0.8 0.27

For ⩾Rew 2000 and ⩾Reg 2000:

=( ) ( )ϕ

dp

dz m

w

dp

dz w

2

; = + +ϕ 1w

Cw

X X

2

1.19

1

2

Rectangular Channel & tube, dH = 0.506 –

12 mm, Horizontal

Sun and Mishima

(2009), [21]

Liquid-gas = − − ∗C Lo21[1 exp( 0.358/ )]

where ⎟=

⎛

⎝

⎜

⎞

⎠

∗

−

Lo d

σm

g ρw ρg

H( )

0.5

⩽ ⩽d0.014 6.25 mmH ; ⩽Re 2000w and ⩽Re 2000g

Modified the Mishima and Hibiki (1996)

correlation

Zhang et al. (2010),

[22]

Water-steam = −−

C x209.5Re (1 )m g

0.29 1.38 Rectangular channel, dH = 3.81 mm, Vertical Qin et al. (2012), [24]

Liquid-liquid (water-

toluene)

=( ) ( )ϕ ;

dp

dz m

w

dp

dz w

2

= = ′ϕ De Ca We7.594( ) 7.594( )w w w w

2 0.0398 0.0398 and

=C De Ca4.92( )w w w

0.07912

Rectangular channel, dH = 3.33 mm,

Horizontal

Present work

Table 6

Comparison of the ϕw

2

values with the other models.

Authors Mean deviation (MD)

(%)

Root mean square deviation

(RMSD) (%)

Chisholm (1967), [15] 81.01 81.07

Tran et al. (1999), [23] 37.32 38.63

Chen et al. (2007), [25] 707.09 708.25

Present correlation 2.09 2.36

Table 7

C –value comparison.

Authors Mean deviation

(MD) (%)

Root mean square deviation

(RMSD) (%)

Mishima et al. (1993), [17] 213.71 216.19

Mishima and Hibiki (1996),

[18]

99.49 99.49

Lee and Lee (2001), [19] 493.29 558.86

Lee and Mudawar (2005),

[20]

66.45 67.49

Sun and Mishima (2009),

[21]

15.28 20.51

Zhang et al. (2010), [22] 16.99 18.89

Qin et al. (2012), [24] 136.48 148.20

Present correlation 2.51 2.72

S. Mondal, S.K. Majumder Experimental Thermal and Fluid Science 94 (2018) 215–230

226](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-s2-180228185958/85/1-s2-0-s0894177718301973-main-12-320.jpg)

![experimental pressure drop values with the values calculated from the

present correlation (modified Ergun) are shown in Fig. 12.

The previously specified correlations for the pressure drop in packed

bed were for the generally cylindrical geometry and for a structured

column. According to our knowledge, no study has been performed till

date using rectangular serpentine packed channels. Due to the variation

in the system geometry from the present study, the pressure drop cal-

culated using the above available correlations indicates a higher de-

viation from the experimental values. But the newly generated modified

Ergun equation shows maximum 5.21% error for both single and

multiphase flow through rectangular serpentine packed channel

[Fig. 12(a), (b)].

The single phase friction factor ′f( )s p and multiphase friction factor

′f( )m p for the flow through the packed channel can be obtained by the

Eqs. (53) and (54) respectively. Different correlations for the flow

through the packed channel are represented (Table 10) and compared

with the present proposed correlation. The model proposed by Mon-

tillet et al. [41] satisfies the experimental results better with root means

square deviation error 15.14% for the multiphase flow (Table 11).

Table 8

Correlations for friction factor as per different investigators for unpacked channel.

Authors & Years Friction factor correlations Channel geometry Flow types

Fanning (1896), [37]

=f

dH Pf

ρmUmL

Δ

2 2 For rectangular serpentine channel this equation takes the form

=

+

f

rcθc

w h Pf

ρmQm h w

180

Π

3 3Δ

2 ( )

Rectangular serpentine

channel

Fully developed flow

Blasius (1913), [26] = −f 0.0791Re 0.25

where < <2000 Re 105

Circular tube as well as

Rectangular channel

Fully developed

turbulent flow

Shah and London (1978), Harnett and

Kostic (1989), Abdelall et al.

(2005), Hrnjak and Tu (2007),

[27–30]

=f λ24 /Re

Where

=

⎛

⎝

⎜

− +

− + −

⎞

⎠

⎟λ

A A

A A A

1 1.3553 1.9467

1.7012 0.9564 0.2537

C C

C C C

2

3 4 5

Rectangular channel Laminar flow

Hua and Yang (1985), [34]

= ( )f

w

rC

5

Re0.65 2

0.175

where <Re 600

Curved Microchannel Laminar flow regimes

Phillips (1990), [31] = ∗f ARe B

Where = +A 0.09290

x dH

1.01612

/

and = − −B 0.26800

x dH

0.32930

/

; For rectangular

microchannels laminar-equivalent Reynolds number

=

=

∗

+ −

Re

ρmUmdH

μm

ρmUm AC AC dH

μm

[(2 / 3) (11 / 24)(1 / )(2 1 / )]

Rectangular

microchannel

Both developing and

developed flow

regimes

Wang and Liu (2007), [35] = +f f DeRe / Re 0.96194 0.01035C S

0.78715 where

< ⩽De0 450

Curved microchannel Laminar flow regimes

Li and Hibiki (2017), [33]; Churchill

(1977), [32] ′ = ⎡

⎣⎢

+ ⎤

⎦⎥+( )f 8m m A B

8

Re

12 1

( )3/2

1/12

where

=

⎧

⎨

⎪

⎩

⎪

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎫

⎬

⎪

⎭

⎪⎜ ⎟

⎛

⎝

⎞

⎠

+

A 2.457ln

m

k

dH

1

7

Re

0.9

0.27

16

and

= ( )B

m

37530

Re

16

when ⩾Re 3000

Rectangular Channel For both laminar and

turbulent regimes

Present work For the single phase: ′ = × − −f De Ca Fr57.7 10 ( ) ( )s s s s

2 0.3743 2.2106

For the mixture phase:

′ = −f De Ca Fr4.7252( ) ( )m m m m

1.292 3.971

Rectangular serpentine

millichannel

For both laminar and

turbulent flow regimes

Table 9

Deviation of calculated friction factor values from different correlations with the present

experimental data for unpacked channel.

Authors Mean deviation (MD)

(%)

Root mean square deviation

(RMSD) (%)

Single

phase

Multi-

phase

Single

Phase

Multi-phase

Blasius (1913), [26] 98.85 97.69 98.85 97.70

Shah and London (1978),

[27]

95.18 97.81 95.19 97.81

Hua and Yang (1985), [34] 95.89 96.29 95.92 96.31

Phillips (1990), [31] – 97.52 – 97.53

Li and Hibiki (2017), [33];

Churchill (1977), [32]

– 90.85 – 91.06

Present correlation 2.48 1.47 2.94 1.73

Table 10

Important correlations for pressure drop in packed channel [62].

Authors & years Equations

Ergun (1952),

[36]

= +

− −

P μ v vΔ 150 1.75

ε L

ϕpε dp

s

ε Lρ

ϕpdpε

s

(1 )2

2 3 2

(1 )

3

2

Feng (1989),

[38]

= −

( )Re

P

L g

ρ

D

u

ε

Δ 0.106

2

0.25

2

kPa/m; =

−

D dp

ϕ

ε

2

6

2

3(1 )

Foumeny et al.

(1993), [39]

= +

−

+

−

P μ v vΔ 130

ε L

ϕpε dp

s

dH dp

dH dp

ε Lρ

ϕpdpε

s

(1 )2

2 3 2

/

0.335( / ) 2.28

(1 )

3

2

Eisfeld and

Schitzlein

(2001), [40]

= +

− −Pdp

ρvs L

Aw

p

ε

ϕpε

Aw

Bw

ε

ϕpε

Δ

2

154 2

Re

(1 )2

2 3

1

3 where = +

−

A 1w dH dp ε

2

3( / )(1 )

and = ⎡

⎣⎢

+ ⎤

⎦⎥( )B 1.15 0.87w

dp

dH

2 2

Montillet et al.

(2007), [41] ⎜ ⎟=

⎛

⎝

+ +

⎞

⎠

−

− −

( )0.061 ( ) 12

Pdp

Lρvs

ε

ε

dH

dp

p

ϕp

p

ϕp

Δ

2

1

3

0.20

1000Re 1

2

60Re 0.5

Newly developed

modified

Ergun

equation

(present

work)

⎛

⎝

⎞

⎠

= ×

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

−

−

−

9.51 10

Pf

L

s p

μvs ε

ϕpdpε

ρvs ε

ϕpdpε

Δ

,

4 (1 )2

2 2 3

0.468

(1 )

3

0.427

and

⎛

⎝

⎞

⎠

= ×

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

− −

1.895 10

Pf

L

m p

μvs ε

ϕpdpε

ρvs ε

ϕpdpε

Δ

,

4 (1 )2

2 2 3

0.155

(1 )

3

0.149

S. Mondal, S.K. Majumder Experimental Thermal and Fluid Science 94 (2018) 215–230

227](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-s2-180228185958/85/1-s2-0-s0894177718301973-main-13-320.jpg)

![The experimental pressure drop in the packed channel is plotted

against predicted values from available correlations, which is shown in

Fig. 13. From the Table 11 and Fig. 13, it is seen that most of the

correlation shows high deviation from the experimental data. Max-

imum deviation is 174.02% for single phase and 224.74% for multi-

phase flow. Among them, Montillet et al. [41] correlation predict closer

results with the experimental values, maximum mean 49.39% for single

phase and 12.94% for multiphase flow. On the other hand, the best

fitting expression for the single-phase flow is given by Eisfeld and

schnitzlein [40] having maximum 39.04% error.

5. Conclusions

The present study enunciates the frictional pressure drop correla-

tions available for the rectangular straight channel as well as the curved

channel. Pressure drop results from the present study are not predicted

well with the available correlation as the geometry and the flowing

fluids are different. Therefore, the new correlations are developed for

the present geometry and fluid systems based on the concept of dif-

ferent models. Based on the present work, the following conclusions can

be made:

a. Pressure drop and friction factor for both single and multiphase flow

through empty or packed rectangular serpentine channel are highly

dependent on Dean Number. The effect of Froude number is more

for multiphase flow than the single phase flow.

b. The measured single phase and multiphase frictional pressure drop

data for the flow through the rectangular serpentine channel

without packing matched well with the developed correlations with

a maximum error of ± 5%.

c. The empirical correlations for the friction factor, two-phase friction

multiplier, and the Chisholm constant also satisfied the calculated

data from the experiment for the flow through the same unpacked

channel with a maximum error of ± 5%.

d. The single and multiphase frictional pressure drop correlations for

the flow through packed bed having above specified geometry clo-

sely resembled the experimental data with a maximum error

of ± 6%.

e. Finally, the Ergun equation, used in the packed channel pressure

Table 11

Deviations of the calculated data for pressure drop from correlation with the present

experimental data for packed channel.

Authors Mean deviation (MD)

(%)

Root mean square deviation

(RMSD) (%)

Single

Phase

Multi-

phase

Single

Phase

Multi-phase

Ergun (1952), [36] 67.07 171.26 83.68 174.41

Feng (1989), [38] 50.01 93.95 55.38 99.54

Foumeny et al. (1993), [39] 63.54 136.12 79.14 139.14

Eisfeld and Schitzlein

(2001), [40]

39.04 53.02 46.85 57.25

Montillet et al. (2007), [41] 49.39 12.94 56.53 15.14

Newly developed modified

Ergun equation

(present work)

1.77 1.90 2.08 2.51

(a)

0 2 4 6 8 50 55 60 65 70

0

2

4

6

8

50

55

60

65

70

Chisholm [3]

Tran et al. [11]

Chen et al. [12]

Present correlation

(Eq. (49))

φw

2

-predicted(-)

φw

2

- experimental (-)

(b)

0 2 4 6 8 30 40 50 60 70

0

2

4

6

8

30

40

50

60

70

PredictedC-value(-)

Experimental C - value (-)

Mishima and Hibiki [18]

Mishima et al. [17]

Lee and Lee [19]

Lee and Mudawar [20]

Sun and Mishima [21]

Zhang et al. [22]

Qin et al. [24]

Present correlation (Eq. (52))

Fig. 10. Comparison of the experimental values with the models: (a) ϕw

2

value comparison and (b) C value comparison.

(a)

0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 20.0 25.0 30.0 35.0 40.0

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

20.0

25.0

30.0

35.0

40.0

2.92%

-5.13%

4.29%

-4.68%

(ΔPf

/L)s

×10

-4

-predicted(N/m

3

)

(ΔPf

/L)s

×10

-4

- experimental (N/m

3

)

Packed channel

Unpacked channel

(b)

0.0 0.5 1.0 4 6 8 10

0.0

0.5

1.0

4

6

8

10

-5.30%

+4.37%

-5.08%

+3.56%

Packed channel

Unpacked channel

(ΔPf

/L)m

×10

-5

-predicted(N/m

3

)

(ΔPf

/L)m

×10

-5

- experimental (N/m

3

)

Fig. 11. Comparison of experimental and predicted pressure drop values for unpacked channel: (a) single phase flow and (b) multiphase flow.

S. Mondal, S.K. Majumder Experimental Thermal and Fluid Science 94 (2018) 215–230

228](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-s2-180228185958/85/1-s2-0-s0894177718301973-main-14-320.jpg)

![drop calculations has been modified. The modified Ergun equation

fits the experimental data well.

The geometry of the rectangular serpentine channel used in the

present study can be scaled up by numbering up approach. Our pro-

posed correlations based on the present experiment may be used for the

design of millichannel based multiphase unit. The present study may be

useful for further understanding of multiphase flow through milli or

microchannel based devices applied for process intensification. The

rectangular serpentine channel in packed condition is highly re-

commended for intense mixing and mass transfer at the cost of high

frictional pressure loss.

References

[1] P. Mary, V. Studer, P. Tabeling, Microfluidic droplet-based liquid-liquid extraction,

Anal. Chem. 80 (2008) 2680–2687.

[2] A.F. Seibert, J.R. Fair, Hydrodynamics and mass transfer in spray and packed liquid-

liquid extraction columns, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 27 (3) (1988) 470–481.

[3] F. Esmaeilzadeh, R. Lashkarboluki, M. Lashkarbolooki, A.Z. Hezave, Modeling of

spearmint oil extraction in a packed bed using sc-co2, Chem. Eng. Commun. 201 (3)

(2014) 300–322.

[4] A. Sahu, A.B. Vir, L.N.S. Molleti, S. Ramji, S. Pushpavanam, Comparison of liquid-

liquid extraction in batch systems and micro-channels, Chem. Eng. Process. 104

(2016) 190–200.

[5] C. Priest, J. Zhou, R. Sedev, J. Ralston, A. Aota, K. Mawatari, T. Kitamori,

Microfluidic extraction of copper from particle-laden solutions, Int. J. Miner.

Process. 98 (2011) 168–173.

[6] M. Darekar, K.K. Singh, S. Mukhopadhyay, K.T. Shenoy, Single-stage micro-scale

extraction: Studies with single microbore tubes and scale-up, Sep. Sci. Technol. 158

(2016) 160–170.

[7] F.H. Kriel, G. Holzner, R.A. Grant, S. Woollam, J. Ralston, C. Priest, Microfluidic

solvent extraction, stripping, and phase disengagement for high-value platinum

chloride solutions, Chem. Eng. Sci. 138 (2015) 827–833.

[8] D. Tsaoulidis, P. Angeli, Effect of channel size on mass transfer during liquid–liquid

plug flow in small scale extractors, Chem. Eng. J. 262 (2015) 785–793.

[9] E.J. Gudina, J.F.B. Pereira, R. Costa, J.A.P. Coutinho, J.A. Teixeira, L.R. Rodrigues,

Biosurfactant-producing and oil-degrading Bacillus subtilis strains enhance oil re-

covery in laboratory sand-pack columns, J. Hazard. Mater. 261 (2013) 106–113.

[10] W. Bigui, L. Jianlin, W. Gang, C. Qing, Filtration of oil from oily wastewater via

hydrophobic modified quartz sand filter medium, J. Water Reuse and Desalination,

In press (2018). doi:10.2166/wrd.2018.052.

[11] K.A. Varteressian, M.R. Fenske, Liquid-liquid extraction performance of a packed

extraction column, using continuous countercurrent operation, Ind. Eng. Chem. 28

(8) (1936) 928–933.

[12] D.H. Moorhead, D.M. Himmelblau, Optimization of operating conditions in a

packed liquid-liquid extraction column, Ind. Eng. Chem. Fundam. 1 (1) (1962)

68–72.

[13] M. Norouzi, N. Biglari, An analytical solution for dean flow in curved ducts with

rectangular cross section, Phys. Fluids 25 (053602) (2013) 1–15.

[14] R.W. Lockhart, R.C. Martinelli, Proposed correlation of data for isothermal two-

phase, two-component flow in pipes, Chem. Eng. Prog. 45 (1) (1949) 39–48.

[15] D. Chisholm, A theoretical basis for the Lockhart-Martinelli correlation for two-

phase flow, Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 10 (12) (1967) 1767–1778.

[16] K. Moriyama, A. Inoue, H. Ohira, The thermohydraulic characteristics of twophase

flow in extremely narrow channels (the frictional pressure drop and void fraction of

adiabatic two-component two-phase flow), Trans. JSME (Ser. B) 58 (1992)

401–407.

[17] K. Mishima, T. Hibiki, H. Nishihara, Some characteristics of gas–liquid flow in

narrow rectangular ducts, Int. J. Multiphase Flow 19 (1993) 115–124.

[18] K. Mishima, T. Hibiki, Some characteristics of air-water two-phase flow in small

diameter vertical tubes, Int. J. Multiphase Flow 22 (4) (1996) 703–712.

[19] H.J. Lee, S.Y. Lee, Pressure drop correlations for two-phase flow within horizontal