1 PHY 241 Fall 2018 PHY 241 Lab 6- Law of Conservation o.docx

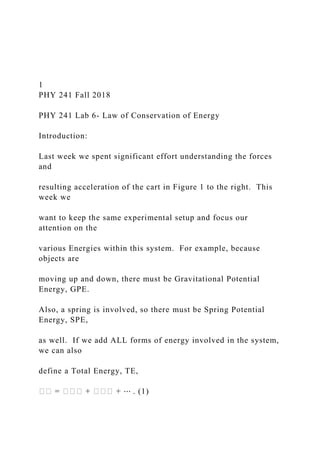

- 1. 1 PHY 241 Fall 2018 PHY 241 Lab 6- Law of Conservation of Energy Introduction: Last week we spent significant effort understanding the forces and resulting acceleration of the cart in Figure 1 to the right. This week we want to keep the same experimental setup and focus our attention on the various Energies within this system. For example, because objects are moving up and down, there must be Gravitational Potential Energy, GPE. Also, a spring is involved, so there must be Spring Potential Energy, SPE, as well. If we add ALL forms of energy involved in the system, we can also define a Total Energy, TE, �� = ��� + ��� + ⋯ . (1)

- 2. The Total Energy is a very useful idea because the Law of Conservation of Energy promises us that the Total energy will behave in a very specific, simple way. The Law of Conservation of Energy states: “The total amount of energy in a system is a constant unless energy is transferred through the system boundary through Work, Heat, Electrical Transmission, etc.” This single statement gives us a series of concrete goals. A. Calculate, ��� and ��� for each time step at which we collected data. B. Plot each form of Energy over multiple bounces of the cart. Also add �� to the graph below. Does the behavior of the Total Energy agree with the Law of Conservation of energy stated above? spring �2 �

- 3. ����� Pulley Figure 1 H 0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1 E n e rg y ( j) Time (s) All Energies? GPE SPE

- 4. 2 PHY 241 Fall 2018 C. Plot �� over multiple bounces with the Energy axis “zoomed in” so you can evaluate the fluctuations in TE, similar to the “Is TE Constant?” graph below. Worry, ponder, and deliberate whether the changes in TE are due to Random Uncertainty, or some unaccounted form of Energy. D. If possible describe the Energy Transfer involved during your data run both qualitatively and quantitatively. Equipment: (same as last experiment) CBR 2- connected directly to a computer using a USB cable Spring String with loop knots in each end Set of Masses Hook Cart

- 5. Safety glasses Paperclip Pulley 2 m track Bubble level Computer with Logger Pro or Logger Lite and Excel. Procedure: 1) The central goal/question for this lab is: How does the Total Energy of our system change as the cart bounces back and forth multiple times? 2) Take some time to familiarize yourself with the accompanying spreadsheet. You should notice that there is a region for Initial Values. An important part of this lab is figuring out 0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 E n e rg y ( J)

- 6. Time (s) Is TE Constant? TE 3 PHY 241 Fall 2018 what measurements you need to take to supplement the CBR measurements in order to calculate the energies required. Most likely, there are too many columns in the Initial Values and the Data Table. 3) Arrange your equipment to match Figure 1. Figure 2 shows a fast and easy way to connect the different components. Make sure you place the CBR in a location where it can measure either the cart or the hanging mass as it moves. 4) When entering equations in E through L columns make sure you use: a. absolute references ($X$1) when using Initial Value cells. b. relative references (X1) when using Data Table cells. c. Refer to your Prelab for hints to improve the accuracy of your calculations.

- 7. 5) Before leaving the classroom, make sure you email the data out to the entire group and the Teaching Assistant. Please use the subject “Lab 6 data- Section ###, Group ###.” 6) Also clean up your work station and returning small equipment to the appropriate storage. 7) Researcher: Use formulae (and the Word Equation Editor) to explicitly describe how the position data from the CBR was transformed into Stretch and Height data of the spring and hanging mass respectively. 8) Researcher: For each type of energy your group calculate in evaluating TE, provide a formula describing how your group calculated that energy. For example, if you were to consider the work done by the friction inside the pulley you might write: “For each data time step, our group estimates that the friction inside the pulley does work on the system and reduces the total energy by Δ������� = −�ℎ������ ∙ ��������������� ∙ Δ����� , (2)

- 8. Where ��������������� ≈ .1 � �2 (as given in the lab manual) and Δ����� is the distance the cart traveled between adjacent data points.” Notice that symbols are clearly labeled (using the “_” key in the Word Equation Editor to add subscripts to symbols) and new values like ��������������� get a bit of explanation. paperclip Figure 2 4 PHY 241 Fall 2018 9) DA: Creating the two graphs described in the introduction and make sure they are properly formatted, including captions. 10) DA: Determine and report the approximate magnitude of the Random Uncertainty in your Total Energy measurement (with proper rounding and units).

- 9. 11) PI: Calculate the energy transferred into/out of the system based on your data (a graph is a good way to visualize this calculation). Is this consistent with the acceleration of friction measurements you collected in Lab 3? Explain. 12) PI: Evaluate the Law of Conservation of Energy (as given in the intro of this lab manual) in light of your group’s data and analysis. Be as specific as possible in highlighting any deficiencies you see in the Law or in your data. Chapter 8 Anishinaabe Rhetoric I work as a university professor teaching classes in Native American Studies. The standard practice is to have students write evaluations of the course and the instructor at the end of the semester. As I have explained elsewhere, I use a pedagog y informed by Anishinaabe teaching methods.1 As I tell my students, I could teach just like any other professor. But, I ask them, what good would that do anybody? If I taught like any other professor, I would essentially be a brown white man. I want my students to understand that Native Americans

- 10. who try to live by their traditional cultural values are different from mainstream Americans. So, I bring Anishinaabe cultural values into the classroom. In today’s globalized economy, the more experience and exposure students have to people from different cultural backgrounds, the better they will be able to compete. So, it is to the students’ advantage for me to teach as an Anishinaabe. I have the students read the articles on my pedagogical methods so they can better understand my teaching style. However, challenges still persist relating to what can only be called cross-cultural conflict, the largest being the manner in which I stray from my prepared remarks and start to digress. It is not unusual for students to comment negatively on my continual digressions in their course evaluations. As might be imagined, such comments do not look good during the regular reviews professors have to undergo. Comments about my digressions leave me with some explaining to do. So, I have reached a point where I find I have to carefully train my students at the start of the semester on what I am now calling “Anishinaabe rhetoric.” From my experience listening to speakers from different Native nations, I suspect many of the features of Anishinaabe rhetoric apply to other Native American cultures, too. In that regard, the phenomenon in question, then, might be referred to as “Native American rhetoric.” In some

- 11. respects, I have to thank my students for their negative comments. Their comments have got me thinking seriously about the nature of Anishinaabe rhetoric, especially the use of digressions. I have come to the conclusion that Anishinaabe rhetoric is intended to speak from the human heart to the human heart, not from the logical mind to the logical mind. To support my claim, I will first look at the use of digressions by Anishinaabe speakers before turning to an 鐨鑔 鑕鑞 鑗鑎 鑌鑍 鑙鐅 � 鐅鐗 鐕鐖 鐙鐓 鐅鐷 鑔鑚 鑙鑑 鑊鑉 鑌鑊 鐓鐅 鐦鑑 鑑鐅 鑗鑎 鑌鑍 鑙鑘 鐅鑗 鑊鑘 鑊鑗 鑛鑊

- 14. 鐪鐧鐸鐨鐴鐅鐵鑚鑇鑑鑎鑘鑍鑎鑓鑌鐅鐟鐅鑊鐧鑔鑔鑐鐅鐨鑔鑑鑑鑊鑈鑙鑎鑔鑓 鐅鐍鐪鐧鐸鐨鐴鑍鑔鑘鑙鐎鐅鐒鐅鑕鑗鑎鑓鑙鑊鑉鐅鑔鑓鐅鐚鐔鐜鐔鐗鐕鐖鐛鐅 鐖鐕鐟鐕鐜鐅鐵鐲鐅鑛鑎鑆鐅鐺鐳鐮鐻鐅鐴鐫鐅鐷鐪鐩鐱鐦鐳鐩鐸 鐦鐳鐟鐅鐜鐚鐙鐗鐙鐞鐅鐠鐅鐬鑗鑔鑘鑘鐑鐅鐱鑆鑜鑗鑊鑓鑈鑊鐅鐼鑎鑑鑑鑎鑆 鑒鐓鐠鐅鐦鑓鑎鑘鑍鑎鑓鑆鑆鑇鑊鐅鐼鑆鑞鑘鐅鑔鑋鐅鐰鑓鑔鑜鑎鑓鑌鐅鑆鑓鑉 鐅鐧鑊鑎鑓鑌 鐦鑈鑈鑔鑚鑓鑙鐟鐅鑘鐝鐙鐗鐙鐞鐜鐞 Anishinaabe Ways of Knowing and Being170 explanation of how to listen to digressions. I will finish with remarks comparing Anishinaabe styles of argumentation with those found in mainstream society and in other cultures. During one of my explanations concerning the nature of digressions in Native American rhetoric in one of my classes, a student brought up an example of an event we had both attended. The difference in our reactions to the same event is rather telling. At this event, an elder was asked what my student took to be a well thought out and well considered question. The elder proceeded to not address the question directly, but went on a long, rambling discourse that seemed to cover everything but the subject that was at the heart of the matter. The student in my class took this to be very rude on the part of the elder. In his opinion, the person asking the question had obviously put a lot

- 15. of thought into the matter and so deserved a direct answer. In the student’s opinion, then, the elder was very rude to not answer the question by going off on one digression after another. My take on the matter was completely different. I told the class that when it was clear the elder intended to go off on a long, rambling discourse, I sat up and got excited. For me, this was an opportunity to listen to wisdom. So I thought the elder was not being rude at all, but was doing all of us a favor by engaging in a digression-filled response. As we continued our conversation, it became evident that the students who had been at the event, who were all non- Indians, tuned out what the elder had to say. They were in general agreement with the first student. The digressions of the elder had turned them off. So the non-Indian students were put off by the elder. I was excited by what the elder had to say. How can we account for this difference? As it turns out, important cultural values and assumptions are at work on both sides, the non-Indian and the Indian, that lead to cultural conflict. To begin an examination of this topic, we can explore this phenomenon from the points of view of the speaker and the audience. We will begin with the logic—Anishinaabe logic—informing the speaker. There are four factors that result in the use of digressions in

- 16. Anishinaabe rhetoric. First, the speaker tries to be guided by the spirits as much as possible and, if not the spirits directly, by spiritual values and ways of thinking. Second, the speaker prefers to address what he or she knows directly. Third, the speaker will talk about what he or she thinks the audience needs to hear. Finally, the speaker tries to speak from the heart as much as possible. We will explore these issues in turn. Being guided by the spirits, or at least speaking on the basis of spiritual values and ways of thinking, can be a difficult topic to understand. Being guided by 鐨鑔 鑕鑞 鑗鑎 鑌鑍 鑙鐅 � 鐅鐗 鐕鐖 鐙鐓 鐅鐷 鑔鑚 鑙鑑 鑊鑉 鑌鑊 鐓鐅 鐦鑑 鑑鐅 鑗鑎 鑌鑍

- 19. 鑎鑌 鑍鑙 鐅鑑 鑆鑜 鐓 鐪鐧鐸鐨鐴鐅鐵鑚鑇鑑鑎鑘鑍鑎鑓鑌鐅鐟鐅鑊鐧鑔鑔鑐鐅鐨鑔鑑鑑鑊鑈鑙鑎鑔鑓 鐅鐍鐪鐧鐸鐨鐴鑍鑔鑘鑙鐎鐅鐒鐅鑕鑗鑎鑓鑙鑊鑉鐅鑔鑓鐅鐚鐔鐜鐔鐗鐕鐖鐛鐅 鐖鐕鐟鐕鐜鐅鐵鐲鐅鑛鑎鑆鐅鐺鐳鐮鐻鐅鐴鐫鐅鐷鐪鐩鐱鐦鐳鐩鐸 鐦鐳鐟鐅鐜鐚鐙鐗鐙鐞鐅鐠鐅鐬鑗鑔鑘鑘鐑鐅鐱鑆鑜鑗鑊鑓鑈鑊鐅鐼鑎鑑鑑鑎鑆 鑒鐓鐠鐅鐦鑓鑎鑘鑍鑎鑓鑆鑆鑇鑊鐅鐼鑆鑞鑘鐅鑔鑋鐅鐰鑓鑔鑜鑎鑓鑌鐅鑆鑓鑉 鐅鐧鑊鑎鑓鑌 鐦鑈鑈鑔鑚鑓鑙鐟鐅鑘鐝鐙鐗鐙鐞鐜鐞 Anishinaabe Rhetoric 171 the spirits does not mean one is “channeling” the spirits in some kind of New Age trance. So it is not as if the spirits take possession of the speaker and use the speaker’s body to make their voices heard. It is also not the case the spirits are somehow standing behind the speaker and directing the speaker what to say. Instead, a different process is at work. I heard an Anishinaabe spiritual leader talk about this process once. It was very informative. In this case, the individual, who will remain anonymous, was talking about how he got ready to make speeches he was scheduled to give. In other words, he was talking about his speech writing process, such as it was. This individual explained that he did

- 20. not write down his speeches ahead of time. In fact, he positively wanted to avoid writing things down. From his point of view, writing things down would act more as a hindrance than a help. He also did not want to be limited by the words that were on the paper in front of him. Instead, he said he engaged in a process of thinking deeply on the topic in a prayerful manner. In this manner, he constructed a general plan about what he wanted to say. However, as can be seen, this process also leaves a lot of leeway for him to change his plan on the fly, and be guided by the needs of the moment. Those needs of the moment can, and often do, involve engaging in digressions. Being informed by spiritual values works in a somewhat similar fashion, but has its own dynamic. A situation of this type occurs during extemporaneous speaking, that is, when one has not had the chance to plan out one’s talk ahead of time. Under these circumstances, the question arises as to what should form the foundation of one’s remarks. Should the remarks be guided more by constructing a logical argument on the fly, or should one be guided by spiritual values? While speaking on the basis of spiritual values does not preclude the possibility of constructing a logical argument, it is not necessary. In fact, in some ways trying to speak on the basis of logic can be more of a hindrance than a

- 21. help. Spiritual values work via their own internal logic that do not necessarily match the dictates of formal logic. Oftentimes, spiritual values are taken as an a priori argument as well. They exist without having to establish a justification for them. Long experience has already established the truth of spiritual values. So instead of constructing a logical argument, the speaker is more apt to draw out the consequences of the topic of discussion based on spiritual values. Since those consequences can be many and varied, and do not necessarily follow in logical order, the speaker may present a series of statements that may not appear to be connected on the surface, but are on a deeper level. So while on the surface the comments may appear rambling and disconnected, they are actually flowing from the same source.鐨鑔 鑕鑞 鑗鑎 鑌鑍 鑙鐅 � 鐅鐗 鐕鐖 鐙鐓 鐅鐷 鑔鑚 鑙鑑 鑊鑉 鑌鑊 鐓鐅

- 24. 鑑鑊 鐅鑈 鑔鑕 鑞鑗 鑎鑌 鑍鑙 鐅鑑 鑆鑜 鐓 鐪鐧鐸鐨鐴鐅鐵鑚鑇鑑鑎鑘鑍鑎鑓鑌鐅鐟鐅鑊鐧鑔鑔鑐鐅鐨鑔鑑鑑鑊鑈鑙鑎鑔鑓 鐅鐍鐪鐧鐸鐨鐴鑍鑔鑘鑙鐎鐅鐒鐅鑕鑗鑎鑓鑙鑊鑉鐅鑔鑓鐅鐚鐔鐜鐔鐗鐕鐖鐛鐅 鐖鐕鐟鐕鐜鐅鐵鐲鐅鑛鑎鑆鐅鐺鐳鐮鐻鐅鐴鐫鐅鐷鐪鐩鐱鐦鐳鐩鐸 鐦鐳鐟鐅鐜鐚鐙鐗鐙鐞鐅鐠鐅鐬鑗鑔鑘鑘鐑鐅鐱鑆鑜鑗鑊鑓鑈鑊鐅鐼鑎鑑鑑鑎鑆 鑒鐓鐠鐅鐦鑓鑎鑘鑍鑎鑓鑆鑆鑇鑊鐅鐼鑆鑞鑘鐅鑔鑋鐅鐰鑓鑔鑜鑎鑓鑌鐅鑆鑓鑉 鐅鐧鑊鑎鑓鑌 鐦鑈鑈鑔鑚鑓鑙鐟鐅鑘鐝鐙鐗鐙鐞鐜鐞 Anishinaabe Ways of Knowing and Being172 For example, the speaker might be asked a question about some aspect of the religious tradition of the culture, and the speaker will suddenly start talking about his or her grandmother’s cooking. On the surface, and for those not familiar with the tradition, it might seem as if the speaker is totally incoherent. However, in the mind of the speaker, the religion of the culture may not be imagined so much as a belief system but more as the basis of one’s action. Also, talking about cooking may serve as a holographic devise. In a hologram, one

- 25. part of the image can be used to conjure up the whole image. Thus, for example, in Anishinaabe culture, most of the food sources have sacred stories connected with them. Gathering and preparing food, then, becomes a religious act in and of itself. So grandmother’s act of cooking can be a part of the religious tradition of the culture. The spiritual values being expressed by that act are many. The act represents a bond with the spiritual world. It serves as evidence of that bond. It is a reminder to act in a respectful manner toward food sources. It celebrates the bonds that exist between the spiritual world and the human. It also reinforces the bonds that exist between human beings in the act of taking care of one another. And these are only a small sample of the many ways grandmother’s cooking relates to the religion of the culture. So even though on the surface the speaker may not appear to be addressing the question, in fact, on a very deep level, the speaker is, in fact, doing just that. On the surface, though, especially to a non-Indian not versed in Native American rhetoric, the comments would appear to be utter nonsense. The non-Indian might be left with the impression that the speaker is rude or incoherent or insane or worse. So this is one way in which Native American rhetoric can lead to acute levels of cross-cultural misunderstanding and conflict.

- 26. Closely related to the above example is the tendency for speakers to talk in terms of their own personal experience. This has to do with Anishinaabe and other nations’ ideas regarding epistemolog y, which deals with understanding knowledge and how we come to achieve knowledge. Of course, it is true that the Anishinaabeg and other Native people can think and talk in abstract terms if so desired. However, knowledge based in experience is preferred. The preference for experiential knowledge is due to a number of reasons. Perhaps first and foremost, it has to do with the understanding of how knowledge comes to individuals. One of the more interesting examples of this concerns the teaching of the Yankton Lakota elder, Maria Pearson, who we met in Chapter 1. I related this story in my article on Anishinaabe pedagog y, but it is worth repeating here.2 She told the story of two young Indians at a powwow. The one looked up and then told the other to check out the eagles above them. Two white men were 鐨鑔 鑕鑞 鑗鑎 鑌鑍 鑙鐅 � 鐅鐗 鐕鐖 鐙鐓 鐅鐷

- 29. 鑆鑕 鑕鑑 鑎鑈 鑆鑇 鑑鑊 鐅鑈 鑔鑕 鑞鑗 鑎鑌 鑍鑙 鐅鑑 鑆鑜 鐓 鐪鐧鐸鐨鐴鐅鐵鑚鑇鑑鑎鑘鑍鑎鑓鑌鐅鐟鐅鑊鐧鑔鑔鑐鐅鐨鑔鑑鑑鑊鑈鑙鑎鑔鑓 鐅鐍鐪鐧鐸鐨鐴鑍鑔鑘鑙鐎鐅鐒鐅鑕鑗鑎鑓鑙鑊鑉鐅鑔鑓鐅鐚鐔鐜鐔鐗鐕鐖鐛鐅 鐖鐕鐟鐕鐜鐅鐵鐲鐅鑛鑎鑆鐅鐺鐳鐮鐻鐅鐴鐫鐅鐷鐪鐩鐱鐦鐳鐩鐸 鐦鐳鐟鐅鐜鐚鐙鐗鐙鐞鐅鐠鐅鐬鑗鑔鑘鑘鐑鐅鐱鑆鑜鑗鑊鑓鑈鑊鐅鐼鑎鑑鑑鑎鑆 鑒鐓鐠鐅鐦鑓鑎鑘鑍鑎鑓鑆鑆鑇鑊鐅鐼鑆鑞鑘鐅鑔鑋鐅鐰鑓鑔鑜鑎鑓鑌鐅鑆鑓鑉 鐅鐧鑊鑎鑓鑌 鐦鑈鑈鑔鑚鑓鑙鐟鐅鑘鐝鐙鐗鐙鐞鐜鐞 Anishinaabe Rhetoric 173 standing behind the Indians. The one looked up and said, “Some Indians. They can’t even tell buzzards from eagles.” Maria’s take on this story is pertinent to our discussion here. Her take on the story was that rather than insult the Indians, the white men should have been asking themselves why they saw buzzards when the Indians saw eagles. To explain a bit further, Maria

- 30. explained that from her point of view, the things we experience are put here by the Creator for us to experience uniquely on an individual basis. So, while it is true that we can have shared experiences, the exact nature of the experience will depend on what the Creator put there for us to experience individually. I had the opportunity to share this story with an Anishinaabe. It was interesting in that not only did he concur with Maria’s take on epistemolog y, he offered his own story to further support that observation. He related that he was at a powwow in Canada when he looked up and, outside the arena circle on the other side from where he was sitting, he saw four bison. He turned to his friend who was sitting next to him and told his friend to look at the bison. When the Anishinaabe looked backed, the bison were gone. His take on that experience was that the Creator put the bison there for him to see, not others. So, of course when his friend looked up, the bison were gone. The Anishinaabe who told me this story was not sure why the Creator put those bison there for him to see, but he was convinced he was meant to have the experience. The teachings of Maria and the story the Anishinaabe told both indicate why, fundamentally, the Anishinaabeg and other Native Americans prefer to speak on the basis of experiential knowledge. As can be seen, from the Anishinaabe point of view,

- 31. experiential knowledge is knowledge that comes from the Creator. In the minds of the Anishinaabeg, there can be no greater or more reliable source of knowledge than this. If the idea is to convey the best knowledge one has available, it therefore makes logical sense for an individual to speak on the basis of personal experience. The preference for experiential knowledge leads to the same type of confusion discussed in the example above wherein, when asked about the religion of a given tradition, an individual might start talking about his or her grandmother’s cooking. We can further nuance the above example by considering Anishinaabe approaches to epistemolog y. We already considered how talking about cooking can be an appropriate response to a question about religion. We thought about how religion could be conceived as an act rather than a set of beliefs, although, of course, the Anishinaabeg have their belief system. If we add in considerations of Anishinaabe epistemolog y, we can deepen our understanding of the speech act under analysis. If we conceptualize religion as acts, then there is an internal logic to speaking about the acts one has experienced if one wishes to discuss religion.鐨鑔 鑕鑞 鑗鑎 鑌鑍

- 34. 鑓鑉 鑊鑗 鐅鐺 鐓鐸 鐓鐅 鑔鑗 鑆鑕 鑕鑑 鑎鑈 鑆鑇 鑑鑊 鐅鑈 鑔鑕 鑞鑗 鑎鑌 鑍鑙 鐅鑑 鑆鑜 鐓 鐪鐧鐸鐨鐴鐅鐵鑚鑇鑑鑎鑘鑍鑎鑓鑌鐅鐟鐅鑊鐧鑔鑔鑐鐅鐨鑔鑑鑑鑊鑈鑙鑎鑔鑓 鐅鐍鐪鐧鐸鐨鐴鑍鑔鑘鑙鐎鐅鐒鐅鑕鑗鑎鑓鑙鑊鑉鐅鑔鑓鐅鐚鐔鐜鐔鐗鐕鐖鐛鐅 鐖鐕鐟鐕鐜鐅鐵鐲鐅鑛鑎鑆鐅鐺鐳鐮鐻鐅鐴鐫鐅鐷鐪鐩鐱鐦鐳鐩鐸 鐦鐳鐟鐅鐜鐚鐙鐗鐙鐞鐅鐠鐅鐬鑗鑔鑘鑘鐑鐅鐱鑆鑜鑗鑊鑓鑈鑊鐅鐼鑎鑑鑑鑎鑆 鑒鐓鐠鐅鐦鑓鑎鑘鑍鑎鑓鑆鑆鑇鑊鐅鐼鑆鑞鑘鐅鑔鑋鐅鐰鑓鑔鑜鑎鑓鑌鐅鑆鑓鑉 鐅鐧鑊鑎鑓鑌 鐦鑈鑈鑔鑚鑓鑙鐟鐅鑘鐝鐙鐗鐙鐞鐜鐞 Anishinaabe Ways of Knowing and Being174 As we saw above, Anishinaabe approaches to epistemolog y posit that one’s experiences are put here for the individual by the Creator. In

- 35. some respects, then, the experiences one has had become the highest form of knowledge. It is, in effect, knowledge that has been bestowed on an individual by the Creator. This is not to say that other forms of knowledge are not valued, such as book learning. This also does not preclude the possibility of learning from the experiences of others, which is a topic we will return to below when we discuss how to listen to Anishinaabe rhetoric. Instead, what we find at work here is the highest respect being given to knowledge that comes to us from the spiritual realm. We also want to keep in mind that the types of experience under discussion here are extremely inclusive in nature. Thus, not only are one’s waking experiences important, but one’s dream experiences are as well. In some ways dream experiences are more important than waking reality. In the dream state, according to Anishinaabe thinking, one is able to interact with the spiritual realm more directly. Now, it is true I heard one Anishinaabe spiritual leader, who shall remain unnamed, discuss the nature of dream experiences. He stated that not all dreams are created equal. Some dreams are more important than others, and some can be discarded completely. It is first and foremost up to the individual to determine the relative significance of any given dream. From my own dream experiences, I would have to concur with this Anishinaabe spiritual leader. I prefer to not

- 36. go into the exact nature of any of my dreams. I will simply say that some of my dreams have been very powerful, and the impact those dreams have had on me still stays with me to this day. It was also the case that I spent time talking about my dreams with my late spiritual mentor while he was still alive. He took the reality of my dreams very seriously and helped me work through their meaning. So we can include dream experiences in the type of knowledge conveyed to us by the spiritual realm. So if we put together the desire to speak based on spiritual values and the preference for experiential knowledge, we can see there is actually a very thin line between the two, if any at all. As we saw in Chapter 4, Anishinaabemowin, the Anishinaabeg language, is a verb-based language. So rather than think in terms of inherent being, the Anishinaabeg tend to think in terms of action. Spiritual values, then, are something to be expressed more so than conceptualized as things in and of themselves. In thinking this through, one can start to see the relationship between spiritual values and experiential knowledge. Going back to our example of having an Anishinaabe start talking about his or her grandmother’s cooking when asked a question about Anishinaabe religion, we can see the intersection between spiritual values and experiential knowledge. On the one hand, it could

- 37. be said that the degree to which the grandmother in this example is living by 鐨鑔 鑕鑞 鑗鑎 鑌鑍 鑙鐅 � 鐅鐗 鐕鐖 鐙鐓 鐅鐷 鑔鑚 鑙鑑 鑊鑉 鑌鑊 鐓鐅 鐦鑑 鑑鐅 鑗鑎 鑌鑍 鑙鑘 鐅鑗 鑊鑘 鑊鑗 鑛鑊 鑉鐓 鐅鐲 鑆鑞 鐅鑓 鑔鑙 鐅鑇 鑊鐅 鑗鑊 鑕鑗 鑔鑉

- 40. Anishinaabe Rhetoric 175 Anishinaabe values, she is expressing the spiritual values of the Anishinaabeg. Thus, by talking about his or her grandmother’s cooking, the speaker is directly relating his or her experiential knowledge of Anishinaabe religion. How does the speaker know what Anishinaabe religion is? The speaker knows it based on his or her experience. That is, the speaker is using his or her experience to discuss Anishinaabe religion. On a deeper level, to the degree that that experience is in line with Anishinaabe values, the speaker is thus speaking on the basis of spiritual values. This is the way Anishinaabe rhetoric can incorporate speaking on the basis of spiritual values and having a preference for experiential experience. We also said that the speaker prefers to be guided by the spirits. However, being guided by the spirits and speaking on the basis of experience are also interrelated. On the one hand, there is the immediate speech act. As discussed above, a speaker will look to the spirits for help in being guided as to what to say. But the speaker also has his or her experiences to draw on, too. Those experiences were teachings provided by the spirits for the individual. In coming to those experiences, one has been guided to them by higher spiritual powers. So

- 41. there is an equivalence between being guided by the spirits and speaking on the basis of experience. In some ways, they are the same thing. One’s knowledge and experience come from the same source, the spiritual realm. It should be pointed out that using knowledge gained from others works in the same fashion. It is not unusual to hear an Anishinaabe speaker talk about what he or she learned from somebody else, very commonly an elder or a spiritual mentor. However, we have to keep in mind that the knowledge and experience of those elders and mentors are the same as those of the speaker. That is, Anishinaabe elders and mentors were led to their experiences by spiritual powers. What they experienced was fundamentally spiritual in nature. So on the surface, it might appear an Anishinaabe is straying from the norms of Anishinaabe rhetoric as discussed above when that Anishinaabe talks about the experience of others. However, especially in quoting elders and mentors, the basis of the spiritual values and knowledge are the same. The speaker is simply passing on another individual’s spiritual understanding and knowledge as revealed to the individual by the spirits. So whether the speaker is relying on his or her own experience or that of others, it could be said in either case he or she is being guided by spiritual forces. We have so far covered the first two factors informing

- 42. Anishinaabe rhetoric, being guided by spirits and speaking on the basis of experiential experience. The third factor, talking about what the speaker thinks the audience needs to hear, has its own set of logic. There may be larger issues at work that may not be immediately evident when a speaker addresses a question. Sometimes these 鐨鑔 鑕鑞 鑗鑎 鑌鑍 鑙鐅 � 鐅鐗 鐕鐖 鐙鐓 鐅鐷 鑔鑚 鑙鑑 鑊鑉 鑌鑊 鐓鐅 鐦鑑 鑑鐅 鑗鑎 鑌鑍 鑙鑘 鐅鑗 鑊鑘 鑊鑗 鑛鑊 鑉鐓 鐅鐲 鑆鑞

- 45. 鐖鐕鐟鐕鐜鐅鐵鐲鐅鑛鑎鑆鐅鐺鐳鐮鐻鐅鐴鐫鐅鐷鐪鐩鐱鐦鐳鐩鐸 鐦鐳鐟鐅鐜鐚鐙鐗鐙鐞鐅鐠鐅鐬鑗鑔鑘鑘鐑鐅鐱鑆鑜鑗鑊鑓鑈鑊鐅鐼鑎鑑鑑鑎鑆 鑒鐓鐠鐅鐦鑓鑎鑘鑍鑎鑓鑆鑆鑇鑊鐅鐼鑆鑞鑘鐅鑔鑋鐅鐰鑓鑔鑜鑎鑓鑌鐅鑆鑓鑉 鐅鐧鑊鑎鑓鑌 鐦鑈鑈鑔鑚鑓鑙鐟鐅鑘鐝鐙鐗鐙鐞鐜鐞 Anishinaabe Ways of Knowing and Being176 issues may not be readily apparent to the audience. We find instead that it is necessary for the audience to think for itself. In this regard, it might take some time for the connections to become clear. But these are the types of demands placed on the audience when confronted with Anishinaabe rhetoric. So, as we shall see in more detail below, listening to Anishinaabe rhetoric is indeed an intellectually challenging task. There may also be ways in which the speaker knows the audience better than it knows itself, especially if the speaker is an elder. Knowing the audience better than it knows itself is a variation on the theme we have just been discussing, that is, the speaker addressing larger issues. In this case, the elder may have experience the audience does not and so the elder can see aspects of a topic that may not be clear to the audience. But it may be those larger aspects of the topic that are of critical importance, and so are the ones that are best discussed. So once again we

- 46. are faced with a situation wherein the audience needs to fully engage with the speaker and think very carefully about what is being said. Finally, there may be larger issues of concern to the community that need to be addressed. In this case, the speaker may be talking about issues underlying the topic of concern. So, the issue may have to do with, say, substance abuse in the community, while the speaker starts discussing harvesting traditional foods. The two might not seem related on the surface, but the speaker may, in fact, be addressing a spiritual vacuum in the life in the community. Harvesting traditional foods can be and, really, should be, a spiritual act. Perhaps what the speaker is trying to get at is there needs to be a deeper spiritual life in the community. Nourishing that spiritual life may in turn help to lessen problems with substance abuse. But, if the speaker starts talking about making maple syrup with his grandparents when he was young, the connection may be lost on the audience unless, again, the audience fully engages the speaker and thinks through for themselves the implications of the speaker’s words. Rupert Ross encountered the above situation when he had the job of reading research reports about the traditional justice systems that existed among the Aboriginal people of Canada. He was initially confused by the research reports

- 47. prepared by Aboriginal groups. He was expecting to see information related to dispute resolution in traditional times. Instead, the reports seemed to cover everything but those kinds of issues. What happened was the researchers in the field, many of whom were Aboriginal people fluent in their languages, had of course talked with their elders about the topic. Instead of explaining dispute resolution processes and the like, “the elders would tell them only what they felt their people needed to hear.”3 In the end, what the elders wanted to convey was 鐨鑔 鑕鑞 鑗鑎 鑌鑍 鑙鐅 � 鐅鐗 鐕鐖 鐙鐓 鐅鐷 鑔鑚 鑙鑑 鑊鑉 鑌鑊 鐓鐅 鐦鑑 鑑鐅 鑗鑎 鑌鑍 鑙鑘 鐅鑗 鑊鑘

- 50. 鑆鑜 鐓 鐪鐧鐸鐨鐴鐅鐵鑚鑇鑑鑎鑘鑍鑎鑓鑌鐅鐟鐅鑊鐧鑔鑔鑐鐅鐨鑔鑑鑑鑊鑈鑙鑎鑔鑓 鐅鐍鐪鐧鐸鐨鐴鑍鑔鑘鑙鐎鐅鐒鐅鑕鑗鑎鑓鑙鑊鑉鐅鑔鑓鐅鐚鐔鐜鐔鐗鐕鐖鐛鐅 鐖鐕鐟鐕鐜鐅鐵鐲鐅鑛鑎鑆鐅鐺鐳鐮鐻鐅鐴鐫鐅鐷鐪鐩鐱鐦鐳鐩鐸 鐦鐳鐟鐅鐜鐚鐙鐗鐙鐞鐅鐠鐅鐬鑗鑔鑘鑘鐑鐅鐱鑆鑜鑗鑊鑓鑈鑊鐅鐼鑎鑑鑑鑎鑆 鑒鐓鐠鐅鐦鑓鑎鑘鑍鑎鑓鑆鑆鑇鑊鐅鐼鑆鑞鑘鐅鑔鑋鐅鐰鑓鑔鑜鑎鑓鑌鐅鑆鑓鑉 鐅鐧鑊鑎鑓鑌 鐦鑈鑈鑔鑚鑓鑙鐟鐅鑘鐝鐙鐗鐙鐞鐜鐞 Anishinaabe Rhetoric 177 that for Aboriginal societies, justice was not a reactive system that sprang into action once disruptive behavior occurred. Instead, it was a proactive system that worked to imprint the ways of harmonious living, the good life, on the hearts of the people, thus keeping disputes to a minimum.4 There may be other ways in which the speaker tells the audience what he or she thinks the audience needs to hear, but the above comments should suffice in illustrating the point. However, one other factor should be discussed in regard to this topic. Especially when it comes to elders, the speaker has the prerogative to say whatever he or she wants to say. This is part of the etiquette and ethic of listening to a speaker, especially if one has posed a question. It really is up to the speaker to choose to reply however he or she sees fit. Maybe the

- 51. speaker feels the audience is not ready to hear the truth in regard to a certain matter. Maybe the speaker has larger, totally unrelated concerns, that he or she thinks supersede the question put forth. In fact, there could be myriad reasons for the speaker responding, say, to a question, in a certain manner. To finish this section with a story, an Anishinaabe once told me of an experience he had with an elder. The Anishinaabe lived in Minneapolis. He had a question for an elder who lived on the Red Lake reservation, which is a long drive from Minneapolis. A round trip from Minneapolis to Red Lake can consume an entire weekend. Upon being asked the question, the elder told the Anishinaabe to come back next week. This happened for several weeks in a row. Finally, the elder answered the question. Additionally, the elder stated he wanted to test the sincerity of the Anishinaabe by making him come back every week. So, it can take a lot of patience when confronted with the prerogatives of being an elder. However, as this Anishinaabe found out, the rewards are well worth it. One can be enriched with a lifetime of wisdom—and questions—to mull over. Anishinaabe rhetoric is also driven by a concern for speaking from the heart. Or, it might be better to say, speaking from the heart and the mind. Clearly, when addressing an audience, the speaker has to use his or her

- 52. mental faculties. However, it is just as important for the speaker to listen to the dictates of the heart. There is a side of life that is beyond reason, as captured in the expression that the heart has its reasons that reason knows nothing of. The way of the heart speaks to human and other relations. Above, we discussed the importance of speaking as informed by the spirits and by spiritual values. Speaking from the heart takes those spiritual values and brings them into the realm of the human. In the chapter on silence, we also discussed the importance of heartstrings—making very real connections between people and other living entities. So the main concern in speaking from the heart is the question of how are we going to keep 鐨鑔 鑕鑞 鑗鑎 鑌鑍 鑙鐅 � 鐅鐗 鐕鐖 鐙鐓 鐅鐷 鑔鑚 鑙鑑 鑊鑉 鑌鑊 鐓鐅 鐦鑑 鑑鐅

- 55. 鑔鑕 鑞鑗 鑎鑌 鑍鑙 鐅鑑 鑆鑜 鐓 鐪鐧鐸鐨鐴鐅鐵鑚鑇鑑鑎鑘鑍鑎鑓鑌鐅鐟鐅鑊鐧鑔鑔鑐鐅鐨鑔鑑鑑鑊鑈鑙鑎鑔鑓 鐅鐍鐪鐧鐸鐨鐴鑍鑔鑘鑙鐎鐅鐒鐅鑕鑗鑎鑓鑙鑊鑉鐅鑔鑓鐅鐚鐔鐜鐔鐗鐕鐖鐛鐅 鐖鐕鐟鐕鐜鐅鐵鐲鐅鑛鑎鑆鐅鐺鐳鐮鐻鐅鐴鐫鐅鐷鐪鐩鐱鐦鐳鐩鐸 鐦鐳鐟鐅鐜鐚鐙鐗鐙鐞鐅鐠鐅鐬鑗鑔鑘鑘鐑鐅鐱鑆鑜鑗鑊鑓鑈鑊鐅鐼鑎鑑鑑鑎鑆 鑒鐓鐠鐅鐦鑓鑎鑘鑍鑎鑓鑆鑆鑇鑊鐅鐼鑆鑞鑘鐅鑔鑋鐅鐰鑓鑔鑜鑎鑓鑌鐅鑆鑓鑉 鐅鐧鑊鑎鑓鑌 鐦鑈鑈鑔鑚鑓鑙鐟鐅鑘鐝鐙鐗鐙鐞鐜鐞 Anishinaabe Ways of Knowing and Being178 our relationships healthy and strong ? How, as will be explored in a later chapter, are we going to maintain bimaadiziwin, or the good life? An example of placing an emphasis on healthy relationships might be the question of who is going to profit most from a certain course of action. Is it going to be a small number of people? Will a small number of people profit disproportionately from a proposed course of action? Other questions come into consideration as well, such as the impact of a proposed course of action on our other-than-human relatives. An example of this type of thinking, and this

- 56. type of advocacy, can be found on the White Earth reservation in regard to Rice Lake. Located toward the east side of the reservation, Rice Lake is a large body of water that contains an enormous wild rice bed. In the 1930s when the State of Minnesota was planning Minnesota Route 200, the State proposed building a causeway across the lower end of the lake. The elders objected that it would disrupt the flow of water in Rice Lake and potentially damage the wild rice. The causeway was built anyhow, and, as it turns out, the elders were correct. The elders were speaking from the heart, thinking about their relationship with the lake and wild rice. The State conducted its assessment based on a different set of values. The State won, and Rice Lake has suffered ever since. This is the difference that can result in thinking and speaking with the heart as well as the mind. In a way, speaking from the heart brings all the elements of Anishinaabe rhetoric from the speaker’s point of view together. Spiritual values are certainly important in Anishinaabe rhetoric, but those spiritual values are further refined by how those values play out in human relations. Speaking on the basis of experience gives priority to real-world experience, that is, real world relationships that are the concern of speaking from the heart. Addressing what the speaker thinks the audience needs to hear is also driven by real world

- 57. concerns for maintaining good relations, which are the foundation for living the good life of the Anishinaabeg. So it could be concluded that the heart of Anishinaabe rhetoric is speaking from the heart. As mentioned above, the mental capabilities of the speaker are, of course, important. However, just as importantly, the speaker is putting his or her heart on display as well. The speaker is saying, in essence, this is who I am as a human being. There is no attempt to remove oneself from the issue at hand, no attempt to stand above the fray and be some kind of impartial, detached, objective commentator. From the Anishinaabe point of view, there can be no such thing as an impartial, detached, objective commentator. We are all human beings living in dynamic human relationships. As we saw in the chapter on language, Anishinaabe thinking focuses on processes and events, processes and events in which we are thoroughly embedded by the simple act 鐨鑔 鑕鑞 鑗鑎 鑌鑍 鑙鐅 � 鐅鐗 鐕鐖 鐙鐓 鐅鐷 鑔鑚

- 60. 鑆鑕 鑕鑑 鑎鑈 鑆鑇 鑑鑊 鐅鑈 鑔鑕 鑞鑗 鑎鑌 鑍鑙 鐅鑑 鑆鑜 鐓 鐪鐧鐸鐨鐴鐅鐵鑚鑇鑑鑎鑘鑍鑎鑓鑌鐅鐟鐅鑊鐧鑔鑔鑐鐅鐨鑔鑑鑑鑊鑈鑙鑎鑔鑓 鐅鐍鐪鐧鐸鐨鐴鑍鑔鑘鑙鐎鐅鐒鐅鑕鑗鑎鑓鑙鑊鑉鐅鑔鑓鐅鐚鐔鐜鐔鐗鐕鐖鐛鐅 鐖鐕鐟鐕鐜鐅鐵鐲鐅鑛鑎鑆鐅鐺鐳鐮鐻鐅鐴鐫鐅鐷鐪鐩鐱鐦鐳鐩鐸 鐦鐳鐟鐅鐜鐚鐙鐗鐙鐞鐅鐠鐅鐬鑗鑔鑘鑘鐑鐅鐱鑆鑜鑗鑊鑓鑈鑊鐅鐼鑎鑑鑑鑎鑆 鑒鐓鐠鐅鐦鑓鑎鑘鑍鑎鑓鑆鑆鑇鑊鐅鐼鑆鑞鑘鐅鑔鑋鐅鐰鑓鑔鑜鑎鑓鑌鐅鑆鑓鑉 鐅鐧鑊鑎鑓鑌 鐦鑈鑈鑔鑚鑓鑙鐟鐅鑘鐝鐙鐗鐙鐞鐜鐞 Anishinaabe Rhetoric 179 of going about the world as living, breathing human beings. Given this reality, the Anishinaabeg, then, speak as human beings, and speaking as a human being entails speaking from the heart as much as speaking with the mind. We will have more to say on the importance of speaking from the heart later. Suffice it for now to say, from the point of view of the speaker, speaking on the basis of spiritual

- 61. values, speaking on the basis of experience, addressing the needs of the audience, and speaking from the heart are some of the most important factors informing Anishinaabe rhetoric. The above considerations are some of the factors that go into Anishinaabe rhetoric from the perspective of the speaker. However, there is more to it than that. We also have to think about Anishinaabe rhetoric from the perspective of the listener. It turns out there is a certain art to listening to Anishinaabe rhetoric. One needs to learn the conventions of, and become versed in, listening to Anishinaabe speakers. This is something that takes practice. As a listener, one needs to be aware of several items. Under no circumstances should one tune out a speaker. It is best to not interrupt a speaker, especially an elder, when he or she is speaking. Do not worry if the original question seems not to have been addressed. And finally, learn to work with the fact that most likely a lesson will not be explicitly conferred. We will examine each of these items in turn. As discussed at the beginning of this chapter, my students and I had completely different reactions to an elder when he went off on a long, rambling, digression-filled response to a student’s question. The non- Indian students were turned off by the elder and completely tuned him out. I, on the

- 62. other hand, sat up and got excited. How can we explain this difference? The non- Indian students did not know how to listen to an elder, while I knew what to do. If I wanted to be generous to myself, I would say I was wiser. If I wanted to be honest, I would say it is because I am already an old man. We will split the difference, and simply say I am more “experienced” listening to elders. From my experience, what I have found out is that when an elder starts in on a long, rambling statement, that is the time to sit up and pay attention. The problem and the challenge is that under these circumstances, one does not know what the speaker is going to say. However, there is the very real possibility that the speaker will come up with some gem of wisdom that will speak to oneself in a very deep and profound manner. If not deep and profound, it could be at least enough to give one something to think about. But, as just stated, one does not know when these gems will appear in the speaker’s discourse. There are some ways in which having gems of wisdom randomly scattered in the speech act serves as a rhetorical device to intellectually engage the listener. The knowledge that there will most likely be gems of wisdom 鐨鑔 鑕鑞 鑗鑎 鑌鑍 鑙鐅

- 65. 鑊鑗 鐅鐺 鐓鐸 鐓鐅 鑔鑗 鑆鑕 鑕鑑 鑎鑈 鑆鑇 鑑鑊 鐅鑈 鑔鑕 鑞鑗 鑎鑌 鑍鑙 鐅鑑 鑆鑜 鐓 鐪鐧鐸鐨鐴鐅鐵鑚鑇鑑鑎鑘鑍鑎鑓鑌鐅鐟鐅鑊鐧鑔鑔鑐鐅鐨鑔鑑鑑鑊鑈鑙鑎鑔鑓 鐅鐍鐪鐧鐸鐨鐴鑍鑔鑘鑙鐎鐅鐒鐅鑕鑗鑎鑓鑙鑊鑉鐅鑔鑓鐅鐚鐔鐜鐔鐗鐕鐖鐛鐅 鐖鐕鐟鐕鐜鐅鐵鐲鐅鑛鑎鑆鐅鐺鐳鐮鐻鐅鐴鐫鐅鐷鐪鐩鐱鐦鐳鐩鐸 鐦鐳鐟鐅鐜鐚鐙鐗鐙鐞鐅鐠鐅鐬鑗鑔鑘鑘鐑鐅鐱鑆鑜鑗鑊鑓鑈鑊鐅鐼鑎鑑鑑鑎鑆 鑒鐓鐠鐅鐦鑓鑎鑘鑍鑎鑓鑆鑆鑇鑊鐅鐼鑆鑞鑘鐅鑔鑋鐅鐰鑓鑔鑜鑎鑓鑌鐅鑆鑓鑉 鐅鐧鑊鑎鑓鑌 鐦鑈鑈鑔鑚鑓鑙鐟鐅鑘鐝鐙鐗鐙鐞鐜鐞 Anishinaabe Ways of Knowing and Being180 contained in the speech act, combined with the uncertainty of when those gems might appear, force the listener to become actively engaged intellectually with

- 66. what the speaker is saying. As in my case, once one has enough experience in this regard, one starts to learn the value of paying attention to a speaker. One learns that when a speaker starts in on a long, rambling discourse, that is the time to sit up, pay attention, and get excited because there is a very good chance the speaker will impart to the audience wealth that cannot be measured: gems of wisdom. There is another, more important, aspect of these gems of wisdom that also needs to be considered. It can be the case that long after the well thought out and well considered question is forgotten, the only thing that will stick with an individual is the gem of wisdom he or she was able to glean from the long, rambling response of the speaker. In the future, it will not matter whether or not the speaker directly addressed the question. The only thing of importance will be that wonderful gem of wisdom one holds so dear. Even if the speaker addresses the question to some degree, the most important point a listener might get from the response may not be related to the question at all. This might be one reason my students and I had such different reactions when the elder we have been discussing went off on a long, digression-filled response. I knew the potential that existed to gain gems of wisdom that might be so powerful they could change my life, even if the original question was not

- 67. addressed. In other words, I was looking for something that would stay with me despite the question. My students seemed to think the only value that could be found in a response to a well thought out and well considered question was a response that addressed the question directly. That is, they were looking for something that would stay with them because of the question. When their expectations were not met, they missed an opportunity to hear something that might have stayed with them for the rest of their lives. Seen in this light, it becomes clear why it is important to not tune out a speaker even if he or she goes off on a long, rambling response. It is also a good idea to not interrupt a speaker. It is not unusual for a speaker, especially an elder, to repeat a story or some other piece of information one has heard from that same speaker before. Under this scenario, it is tempting to roll one’s eyes and think, “Here we go again,” and, as with the non- Indian students above, to tune out what the speaker has to say. This is not the approach to take for several reasons. First, one never knows if the speaker is going to add new information one has not heard before. This is particularly true with stories one might have heard from an elder before. This is something that happened to me with a respected elder. She was telling me a story about an incident in her life.

- 68. I do not know how many times I had heard the story before. I was tempted 鐨鑔 鑕鑞 鑗鑎 鑌鑍 鑙鐅 � 鐅鐗 鐕鐖 鐙鐓 鐅鐷 鑔鑚 鑙鑑 鑊鑉 鑌鑊 鐓鐅 鐦鑑 鑑鐅 鑗鑎 鑌鑍 鑙鑘 鐅鑗 鑊鑘 鑊鑗 鑛鑊 鑉鐓 鐅鐲 鑆鑞 鐅鑓 鑔鑙 鐅鑇 鑊鐅 鑗鑊 鑕鑗 鑔鑉

- 71. Anishinaabe Rhetoric 181 to interrupt her and tell her I knew the story and she did not have to tell it to me again. However, being “experienced” as I am, I decided it was best to not interrupt and let her talk as she saw fit. Sure enough, she started adding elements to the story I had never heard before. If I had cut her off, I may never have learned that new information. This incident reinforced for me the importance of not interrupting a speaker even if one is hearing the same information for the umpteenth time. In addition to that, there is another reason why it is good to not interrupt a speaker even if one is hearing the same information one has heard many times before. As with most Native people in the Americas, the Anishinaabe people have an oral tradition. Much of the cultural teachings are passed down by word of mouth. As a result, it is important to cement knowledge in one’s heart and mind as deeply as possible. One way to do this is by listening to the same information any number of times. Most people have a tendency to tell a story or convey information in a set manner. They will use the same phrasing when telling a story and relate the events in a given order. A similar dynamic is often true when conveying other types of information as well. For

- 72. example, processes will be explained with certain phrases and often an emphasis will be placed on the most important part of the knowledge: This is the secret to X. Being “experienced” what I have found is that it helps to listen to that phrasing and try to remember it as closely as possible. This is especially true when it comes to stories. It helps to repeat the story to oneself just as one heard it as much as possible. Now, we know that people construct memories of events and that the way one remembers events is going to be biased. It thus becomes very easy to dismiss personal stories as not containing the truth, or not being a truthful account of the matter. In other words, the speaker is lying. However, this is the wrong attitude. Instead, it is better to respect the speaker. This is the way the speaker remembers the events and wants to convey them. This is the way the speaker wants the events understood. In that regard, then, it is an act of respect, especially toward elders, to try to remember the story the way the elder conveyed it as much as possible. This is how the memory of elders continues. This is how elders continue to live after they have passed on. Seen in this light, it becomes even more understandable why it is important to not interrupt speakers, but to listen, and remember, what they have to say. One should not be put off if a speaker does not answer a

- 73. question directly or does not seem to be addressing a clear-cut topic. It is important to remember that speakers operate on good faith. They are not simply trying to dismiss a question or otherwise evade a topic, generally speaking. Instead, it is better to 鐨鑔 鑕鑞 鑗鑎 鑌鑍 鑙鐅 � 鐅鐗 鐕鐖 鐙鐓 鐅鐷 鑔鑚 鑙鑑 鑊鑉 鑌鑊 鐓鐅 鐦鑑 鑑鐅 鑗鑎 鑌鑍 鑙鑘 鐅鑗 鑊鑘 鑊鑗 鑛鑊 鑉鐓 鐅鐲 鑆鑞 鐅鑓 鑔鑙

- 76. 鑒鐓鐠鐅鐦鑓鑎鑘鑍鑎鑓鑆鑆鑇鑊鐅鐼鑆鑞鑘鐅鑔鑋鐅鐰鑓鑔鑜鑎鑓鑌鐅鑆鑓鑉 鐅鐧鑊鑎鑓鑌 鐦鑈鑈鑔鑚鑓鑙鐟鐅鑘鐝鐙鐗鐙鐞鐜鐞 Anishinaabe Ways of Knowing and Being182 remember many of the features of Anishinaabe rhetoric discussed above, such as speaking from one’s experience and on the basis of spiritual values. Thus, in assuming the speaker is talking in good faith and is using the conventions of Anishinaabe rhetoric, a different approach is called for as opposed to listening to a thesis-driven formal speech or other Western ways of engaging in discourse. It is best to assume the issue is being addressed. Instead, a different dynamic is at work in Anishinaabe rhetoric. As discussed above and in previous chapters, part of the goal of the speaker is to intellectually engage the listener. The connection between what the speaker is saying and the question at hand might not be immediately evident. Instead, the words of the speaker are more like seeds planted in one’s consciousness. Those seeds can be nourished by ruminating on what the speaker said from time to time. It might take a while for the answer to become clear. But once it does, the answer will stay with one much longer, most likely, than if one was not given the chance to make the connections for oneself.

- 77. Closely associated with the above is the idea that in Anishinaabe rhetoric and storytelling, there is no moral to the story, as found in Aesop’s fables, for example. The Anishinaabeg prefer to let the listener figure out the meaning of the story for oneself. In this regard, Jim Northrup, writing in his memoir, The Rez Road Follies: Canoes, Casinos, Computers, and Birch Bark Baskets, provides an example that is worth investigating in more detail. He writes: One of my favorite stories is the time some people sold a rice buyer something other than wild rice. They added a couple of big rocks to increase the weight of the rice sacks. The next day, the rice buyer came back and sold the people some groceries. The people found the same rocks in their flour. … The power of the story comes from our reaction to it. One person could hear it and reaffirm their belief that cheaters never prosper. Another could listen to the same story and say, “Well, we tried that trick on the white man and it didn’t work. We’ll have to come up with a better one than that.” A third could hear nothing beyond the fact that it was a ricing story. They could take a little trip back to the last time they were ricing. The memories would bring smiles. Someone else might say, “Hey, wait a minute, he just stole my

- 78. best story about rocks and rice.” A businessman might say, “What the hay [sic], the guy still made money. The rocks were more valuable as rice than flour.” “I remember my Dad telling this story,” would be another response as yet another listener traveled back in family history to an image of her Dad [sic] laughing, as he told the same story.5 鐨鑔 鑕鑞 鑗鑎 鑌鑍 鑙鐅 � 鐅鐗 鐕鐖 鐙鐓 鐅鐷 鑔鑚 鑙鑑 鑊鑉 鑌鑊 鐓鐅 鐦鑑 鑑鐅 鑗鑎 鑌鑍 鑙鑘 鐅鑗 鑊鑘 鑊鑗

- 81. 鐓 鐪鐧鐸鐨鐴鐅鐵鑚鑇鑑鑎鑘鑍鑎鑓鑌鐅鐟鐅鑊鐧鑔鑔鑐鐅鐨鑔鑑鑑鑊鑈鑙鑎鑔鑓 鐅鐍鐪鐧鐸鐨鐴鑍鑔鑘鑙鐎鐅鐒鐅鑕鑗鑎鑓鑙鑊鑉鐅鑔鑓鐅鐚鐔鐜鐔鐗鐕鐖鐛鐅 鐖鐕鐟鐕鐜鐅鐵鐲鐅鑛鑎鑆鐅鐺鐳鐮鐻鐅鐴鐫鐅鐷鐪鐩鐱鐦鐳鐩鐸 鐦鐳鐟鐅鐜鐚鐙鐗鐙鐞鐅鐠鐅鐬鑗鑔鑘鑘鐑鐅鐱鑆鑜鑗鑊鑓鑈鑊鐅鐼鑎鑑鑑鑎鑆 鑒鐓鐠鐅鐦鑓鑎鑘鑍鑎鑓鑆鑆鑇鑊鐅鐼鑆鑞鑘鐅鑔鑋鐅鐰鑓鑔鑜鑎鑓鑌鐅鑆鑓鑉 鐅鐧鑊鑎鑓鑌 鐦鑈鑈鑔鑚鑓鑙鐟鐅鑘鐝鐙鐗鐙鐞鐜鐞 Anishinaabe Rhetoric 183 There are a number of elements at work in the above passage. First and foremost, I would like to point out something Northrup does not cover. He presents the reactions to the stories as discrete responses by different individuals. It should be kept in mind that in actuality, one person could potentially have two or more of these responses. So an individual might think the person stole the story, but also remember his or her father telling the same story, taking the story to be something of a family possession passed down through the generations. It is also possible for an individual to have different reactions over the course of time as well. For example, when first hearing the story, the listener might remember earlier times harvesting wild rice, but at a later date, might add to his or her understanding of the story that cheaters never prosper. In other words, the

- 82. meaning of the story can grow and mature for an individual as that individual grows and matures. When the above two phenomena, not necessarily directly addressing a topic and not providing a moral of the story, are taken together, other aspects of the logic behind Anishinaabe rhetoric start to become clear. As discussed above in regard to not directly addressing the matter, an answer to a question can become a seed planted in one’s mind, a seed that it is up to the individual to nourish. Not providing the moral of the story functions in much the same manner. Stories become like seeds planted in one’s mind that can grow and then be revisited from time to time to harvest the new wisdom they present. In both cases, the speaker in actuality is asking the listener to think for him or herself. It will be recalled that when we discussed the intellectually challenging mind in Chapter 6, the Anishinaabeg will engage each other with provocative questions. They like to challenge each other to think. Not necessarily answering a question directly and not providing the moral of the story operate in the same manner. Answers and stories become intellectual challenges individuals need to think through for themselves. It is, in effect, a way for the Anishinaabeg to say, “Think for yourself.” It will also be recalled from Chapter 6 that in encouraging

- 83. an individual to think for him or herself, the speaker is also giving the listener one of the greatest gifts of all, the ability to “know thyself.” So, it can be seen why the Anishinaabeg prefer to not necessarily address the topic or provide the moral of the story. Another aspect of the logic at work in the situations we are examining here has to do with the Anishinaabe notion of respect for the autonomy of other individuals. Rupert Ross discussed this matter in his book, Dancing with a Ghost: Exploring Aboriginal Reality. He discusses at some length the ethic of non- interference. I would like to quote two passages regarding that ethic. Quoting 鐨鑔 鑕鑞 鑗鑎 鑌鑍 鑙鐅 � 鐅鐗 鐕鐖 鐙鐓 鐅鐷 鑔鑚 鑙鑑 鑊鑉 鑌鑊 鐓鐅 鐦鑑 鑑鐅 鑗鑎

- 86. 鑞鑗 鑎鑌 鑍鑙 鐅鑑 鑆鑜 鐓 鐪鐧鐸鐨鐴鐅鐵鑚鑇鑑鑎鑘鑍鑎鑓鑌鐅鐟鐅鑊鐧鑔鑔鑐鐅鐨鑔鑑鑑鑊鑈鑙鑎鑔鑓 鐅鐍鐪鐧鐸鐨鐴鑍鑔鑘鑙鐎鐅鐒鐅鑕鑗鑎鑓鑙鑊鑉鐅鑔鑓鐅鐚鐔鐜鐔鐗鐕鐖鐛鐅 鐖鐕鐟鐕鐜鐅鐵鐲鐅鑛鑎鑆鐅鐺鐳鐮鐻鐅鐴鐫鐅鐷鐪鐩鐱鐦鐳鐩鐸 鐦鐳鐟鐅鐜鐚鐙鐗鐙鐞鐅鐠鐅鐬鑗鑔鑘鑘鐑鐅鐱鑆鑜鑗鑊鑓鑈鑊鐅鐼鑎鑑鑑鑎鑆 鑒鐓鐠鐅鐦鑓鑎鑘鑍鑎鑓鑆鑆鑇鑊鐅鐼鑆鑞鑘鐅鑔鑋鐅鐰鑓鑔鑜鑎鑓鑌鐅鑆鑓鑉 鐅鐧鑊鑎鑓鑌 鐦鑈鑈鑔鑚鑓鑙鐟鐅鑘鐝鐙鐗鐙鐞鐜鐞 Anishinaabe Ways of Knowing and Being184 Dr. Clare Brant, a Mohawk Indian and a psychiatrist who worked with Native people in Canada, it becomes clear the ethic of non-interference is a cardinal rule in Anishinaabe society: The principle of non-interference is all-pervasive throughout our entire culture. We are loath to confront people. We are very loath to give advice to anyone if the person is not specifically asking for advice. To interfere or even comment on their behaviour is considered rude. (emphasis added)6 Ross served as a prosecutor for Ontario Province, so he often had to decide the fate of Native people. But he also felt a sincere desire to take

- 87. the Native point of view into consideration as well. He explains his dilemma trying to figure out how to work with the ethic of non-interference in talking with Aboriginal people about the court cases on which he was working : Brant struck an even more responsive chord when he spoke about the impropriety of giving advice, even when it is asked for. … I found it impossible, however, to believe that people had no opinions about such issues; I therefore tried a different approach. I did not ask for advice, or even for a recommendation. Instead, I spoke out loud about the various factors which had to be considered in coming to a decision, as if I were only reviewing them for my own benefit. I let the problems pose themselves, without ever directly expressing them. Then I noticed a change. People started to speak. I had to endure long silences, against my every inclination, but I knew that if I jumped in to fill them the discussion would end. Nothing could be hurried, nor could anyone be interrupted as they too did their thinking out loud. … As I began to learn how to listen, two things became clear. First, contrary to my earlier impression, it was obvious that people not only cared a great deal about things but had also given them a great deal of thought. Second, they most certainly held definite views about what the

- 88. appropriate responses should be. They would not, however, give those views directly. Instead, they would recite and subtly emphasize, often only through repetition, the facts that led towards their preferred conclusion. The listener, of course, had to find that conclusion himself. It became, in that way, his conclusion too.7 So much of what we have been discussing is packed into the above excerpt. For our purposes here, we want to concentrate on the notion of respect for other individuals. As can be seen, it is clear that the speaker often can and does have 鐨鑔 鑕鑞 鑗鑎 鑌鑍 鑙鐅 � 鐅鐗 鐕鐖 鐙鐓 鐅鐷 鑔鑚 鑙鑑 鑊鑉 鑌鑊 鐓鐅 鐦鑑 鑑鐅 鑗鑎 鑌鑍 鑙鑘 鐅鑗

- 91. 鐅鑑 鑆鑜 鐓 鐪鐧鐸鐨鐴鐅鐵鑚鑇鑑鑎鑘鑍鑎鑓鑌鐅鐟鐅鑊鐧鑔鑔鑐鐅鐨鑔鑑鑑鑊鑈鑙鑎鑔鑓 鐅鐍鐪鐧鐸鐨鐴鑍鑔鑘鑙鐎鐅鐒鐅鑕鑗鑎鑓鑙鑊鑉鐅鑔鑓鐅鐚鐔鐜鐔鐗鐕鐖鐛鐅 鐖鐕鐟鐕鐜鐅鐵鐲鐅鑛鑎鑆鐅鐺鐳鐮鐻鐅鐴鐫鐅鐷鐪鐩鐱鐦鐳鐩鐸 鐦鐳鐟鐅鐜鐚鐙鐗鐙鐞鐅鐠鐅鐬鑗鑔鑘鑘鐑鐅鐱鑆鑜鑗鑊鑓鑈鑊鐅鐼鑎鑑鑑鑎鑆 鑒鐓鐠鐅鐦鑓鑎鑘鑍鑎鑓鑆鑆鑇鑊鐅鐼鑆鑞鑘鐅鑔鑋鐅鐰鑓鑔鑜鑎鑓鑌鐅鑆鑓鑉 鐅鐧鑊鑎鑓鑌 鐦鑈鑈鑔鑚鑓鑙鐟鐅鑘鐝鐙鐗鐙鐞鐜鐞 Anishinaabe Rhetoric 185 an idea of what he or she thinks the audience, or, in this case, the conversation partner, needs to hear. But, the speaker is loath to say so directly. That would violate that ethic of non-interference. So advice is often given in circuitous fashion. But even with that, the realization is that in the end it is up to the listener to decide if the speaker’s thoughts on the subject at hand are helpful. The speaker cannot and does not presume to know everything about the listener and is humble in realizing that fact. It would be a matter of immense arrogance to suppose one knows the listener’s heart. Instead, the best the speaker can do is not make an intellectual argument or thesis-driven statement about the matter. Under the ethic of non-interference, it is best for the speaker to speak from the

- 92. heart, to show the listener his or her heart. It is then up to the listener to decide the sincerity of the speaker’s heart for him or herself. And, in the end, that constitutes the core of the listening experience in regard to Anishinaabe rhetoric and, in many ways I would argue, the heart of Anishinaabe rhetoric as a whole. An Anishinaabe speaker speaks from the heart. It is incumbent upon the individual to learn how to listen to that person’s heart. And as we saw above when examining Anishinaabe rhetoric from the point of view of the speaker, speaking from the heart is key to understanding this phenomenon. In bringing this section of the discussion to a close, then, I would like to say a few more words about speaking from the heart. The principle underlying concern in regard to Anishinaabe rhetoric has to do with the question of human character. In speaking from the heart and in listening to the heart of the speaker, the Anishinaabeg are most interested in trying to figure out if the speaker is a person to be trusted. The main question, then, is: Can I trust this person? There are a couple aspects of this approach worth exploring. First, in earlier times, the Anishinaabeg did not have coercive instruments of state. There were no police, no standing armies, no jails, and no judicial system to impose the will of the state on individuals. The term “will

- 93. of the state” should be understood as a euphemism for the rich and powerful who control the instruments of state. So, leaders could not force their will upon the people. Instead, they had to use other instruments to guide and influence the people. The only two tools they had at their disposal were persuasion and example. In the case of leading by example, the leaders in society were, in effect, demonstrating to the people the quality of their character. However, the same is true when it comes to questions of persuasion. The leaders had to demonstrate with their words that they were to be trusted. The device that was developed was the rhetorical conventions we have been addressing here, the conventions of Anishinaabe rhetoric. In speaking from the heart, the leaders were also 鐨鑔 鑕鑞 鑗鑎 鑌鑍 鑙鐅 � 鐅鐗 鐕鐖 鐙鐓 鐅鐷 鑔鑚 鑙鑑 鑊鑉 鑌鑊 鐓鐅 鐦鑑

- 96. 鐅鑈 鑔鑕 鑞鑗 鑎鑌 鑍鑙 鐅鑑 鑆鑜 鐓 鐪鐧鐸鐨鐴鐅鐵鑚鑇鑑鑎鑘鑍鑎鑓鑌鐅鐟鐅鑊鐧鑔鑔鑐鐅鐨鑔鑑鑑鑊鑈鑙鑎鑔鑓 鐅鐍鐪鐧鐸鐨鐴鑍鑔鑘鑙鐎鐅鐒鐅鑕鑗鑎鑓鑙鑊鑉鐅鑔鑓鐅鐚鐔鐜鐔鐗鐕鐖鐛鐅 鐖鐕鐟鐕鐜鐅鐵鐲鐅鑛鑎鑆鐅鐺鐳鐮鐻鐅鐴鐫鐅鐷鐪鐩鐱鐦鐳鐩鐸 鐦鐳鐟鐅鐜鐚鐙鐗鐙鐞鐅鐠鐅鐬鑗鑔鑘鑘鐑鐅鐱鑆鑜鑗鑊鑓鑈鑊鐅鐼鑎鑑鑑鑎鑆 鑒鐓鐠鐅鐦鑓鑎鑘鑍鑎鑓鑆鑆鑇鑊鐅鐼鑆鑞鑘鐅鑔鑋鐅鐰鑓鑔鑜鑎鑓鑌鐅鑆鑓鑉 鐅鐧鑊鑎鑓鑌 鐦鑈鑈鑔鑚鑓鑙鐟鐅鑘鐝鐙鐗鐙鐞鐜鐞 Anishinaabe Ways of Knowing and Being186 demonstrating the quality of their character. Under this scenario, it is not so much the facts of a situation that matter, although, of course, they are not to be dismissed either. Instead, the Anishinaabeg want to know if this is a leader who can be trusted, one who is worth listening to and following. If answered in the affirmative, the leader can then take the steps to do good for the people. If not, the individual will not be entrusted with the reins of power. Although there are of course no guarantees, the expectation is that a leader who exhibits good character, who demonstrates a good heart, will do good for

- 97. the people. So speaking from the heart becomes an important way for the Anishinaabeg to ensure good leadership for the people. There is another aspect to this approach that bears mentioning as well. It is much harder to hide ill intent or a bad character when speaking from the heart as opposed to a thesis-driven argument. One clear example of this observation is the use of thesis-driven arguments by the eugenics movement prior to World War II to “prove” African-Americans and other minorities were inferior. That is, before World War II, the inferiority of minority groups was a proven scientific “fact.” Modern day research has discussed the tremendous dilatory effect this “fact” had on minorities.8 It should be noted that the eugenics movement and the supposed inferiority of Native Americans continued to adversely affect Native Americans well after World War II, the most heart-wrenching manifestation of this attitude being found in the forced sterilization of Native American women by the Indian Health Service in the 1970s.9 Clearly, the use of thesis-driven argumentation has not been kind to minority people over the years. This is not to say all thesis-driven argumentation is bad, or that thesis-driven argumentation has no place in rhetoric, but there can be bad aspects to using it. First, thesis-driven argumentation pretends to be objective

- 98. when, in actuality, there is no objectivity. Any argument will have its underlying suppositions that influence the nature of the argument. Even the choice of which phenomena to investigate is driven by larger concerns. For example, while I was at Iowa State University, research on genetically engineered crops was seeing its funding expanded, while the center for sustainable agriculture suffered severe budget cutbacks. The results of the research into genetically engineered crops may have been objective from a scientific point of view, but the choice of funding priorities speaks volumes about the values at Iowa State when I was there. Second, thesis- driven argumentation tends to be very narrow in its concerns. For example, research on genetically engineered crops might demonstrate their effectiveness in the very narrow sense of increasing yields, but this same research will have nothing to say about other potential effects. Maybe the research on these larger 鐨鑔 鑕鑞 鑗鑎 鑌鑍 鑙鐅 � 鐅鐗 鐕鐖 鐙鐓 鐅鐷 鑔鑚

- 101. 鑆鑕 鑕鑑 鑎鑈 鑆鑇 鑑鑊 鐅鑈 鑔鑕 鑞鑗 鑎鑌 鑍鑙 鐅鑑 鑆鑜 鐓 鐪鐧鐸鐨鐴鐅鐵鑚鑇鑑鑎鑘鑍鑎鑓鑌鐅鐟鐅鑊鐧鑔鑔鑐鐅鐨鑔鑑鑑鑊鑈鑙鑎鑔鑓 鐅鐍鐪鐧鐸鐨鐴鑍鑔鑘鑙鐎鐅鐒鐅鑕鑗鑎鑓鑙鑊鑉鐅鑔鑓鐅鐚鐔鐜鐔鐗鐕鐖鐛鐅 鐖鐕鐟鐕鐜鐅鐵鐲鐅鑛鑎鑆鐅鐺鐳鐮鐻鐅鐴鐫鐅鐷鐪鐩鐱鐦鐳鐩鐸 鐦鐳鐟鐅鐜鐚鐙鐗鐙鐞鐅鐠鐅鐬鑗鑔鑘鑘鐑鐅鐱鑆鑜鑗鑊鑓鑈鑊鐅鐼鑎鑑鑑鑎鑆 鑒鐓鐠鐅鐦鑓鑎鑘鑍鑎鑓鑆鑆鑇鑊鐅鐼鑆鑞鑘鐅鑔鑋鐅鐰鑓鑔鑜鑎鑓鑌鐅鑆鑓鑉 鐅鐧鑊鑎鑓鑌 鐦鑈鑈鑔鑚鑓鑙鐟鐅鑘鐝鐙鐗鐙鐞鐜鐞 Anishinaabe Rhetoric 187 effects will be done. Maybe it will not. Third, with its supposed objectivity and narrow range of focus, it becomes much easier to hide ill will. On the surface, the parties involved may seem to be having a polite conversation about the topic at hand, complete with supporting facts and studies. The results, however, may cover ill will, or at least indifference, toward other people or things. As we saw

- 102. with the case of Rice Lake above, it is doubtful the engineers for the State of Minnesota had any concern for the wild rice crop in deciding to build a causeway across the lake. Of course, it needs to be acknowledged that speaking from the heart can have its down sides as well. For example, it is every bit as possible to hide ill will and bad intent in feigning speaking from the heart. There are smooth talkers in every society. The question in the case of thesis-driven argumentation and smooth talking in the case of Anishinaabe rhetoric is, where are the checks and balances in the system? For the Anishinaabeg, as mentioned above, there is the use of example. If the speaker’s actions do not live up to his or her pretty words, it is going to become apparent quite quickly that in the future the individual is not to be trusted. In the case of thesis-driven argumentation, the same eternal vigilance is called for. However, I would contend it is much harder to hide ill will and bad intent from the start using the Anishinaabe approach. The conventions of listening are just as important as the conventions of speaking when it comes to Anishinaabe rhetoric. Using the conventions of listening outlined above, it is possible to become adroit at determining the quality of the speaker’s heart. It therefore becomes much harder to fool people with pretty words and lofty

- 103. rhetoric. It is much easier to see through those rhetorical ruses by training oneself to be a good listener. In the end it makes it harder for mischief makers to get started in the first place. I will repeat what I said above just to be clear about my position. Thesis- driven argumentation has its place. I even teach it in my own classes. It is an important intellectual tool to have at one’s disposal. But, as I discussed at the beginning of this chapter, I am finding it more and more important to articulate and to teach the conventions of Anishinaabe rhetoric as well. It is not the case that one is better than the other. They both have their places at the right time and under the right circumstances. However, again, as I stated at the beginning of this chapter, it needs to be acknowledged, though, that Anishinaabe rhetoric, and Native American rhetoric in general, has its place as well. It has its own interior logic and functions in its own unique manner. In order to further clarify the special quality of Anishinaabe rhetoric and further justify its legitimacy, 鐨鑔 鑕鑞 鑗鑎 鑌鑍 鑙鐅 � 鐅鐗

- 106. 鐓鐸 鐓鐅 鑔鑗 鑆鑕 鑕鑑 鑎鑈 鑆鑇 鑑鑊 鐅鑈 鑔鑕 鑞鑗 鑎鑌 鑍鑙 鐅鑑 鑆鑜 鐓 鐪鐧鐸鐨鐴鐅鐵鑚鑇鑑鑎鑘鑍鑎鑓鑌鐅鐟鐅鑊鐧鑔鑔鑐鐅鐨鑔鑑鑑鑊鑈鑙鑎鑔鑓 鐅鐍鐪鐧鐸鐨鐴鑍鑔鑘鑙鐎鐅鐒鐅鑕鑗鑎鑓鑙鑊鑉鐅鑔鑓鐅鐚鐔鐜鐔鐗鐕鐖鐛鐅 鐖鐕鐟鐕鐜鐅鐵鐲鐅鑛鑎鑆鐅鐺鐳鐮鐻鐅鐴鐫鐅鐷鐪鐩鐱鐦鐳鐩鐸 鐦鐳鐟鐅鐜鐚鐙鐗鐙鐞鐅鐠鐅鐬鑗鑔鑘鑘鐑鐅鐱鑆鑜鑗鑊鑓鑈鑊鐅鐼鑎鑑鑑鑎鑆 鑒鐓鐠鐅鐦鑓鑎鑘鑍鑎鑓鑆鑆鑇鑊鐅鐼鑆鑞鑘鐅鑔鑋鐅鐰鑓鑔鑜鑎鑓鑌鐅鑆鑓鑉 鐅鐧鑊鑎鑓鑌 鐦鑈鑈鑔鑚鑓鑙鐟鐅鑘鐝鐙鐗鐙鐞鐜鐞 Anishinaabe Ways of Knowing and Being188 I would like to examine Anishinaabe rhetoric in light of other forms of rhetoric and argumentation aside from thesis-driven argumentation. To start off, I want to distinguish Anishinaabe rhetoric from various forms

- 107. of speaking found in mainstream society, particularly extemporaneous speaking and stream of consciousness speaking. I will examine these in turn, starting with extemporaneous speaking. I am using the term “extemporaneous speaking” here as a technical term used in speech competitions. Without going into too much detail, extemporaneous speaking is a style of speech making in speech contests in which the contestant has a limited amount of time to develop a coherent speech, which must be delivered without the aid of notes. Several factors go into judging extemporaneous speaking ; however, if we were to sum up these factors as a whole, in effect the contestant is asked to construct a standard thesis- driven essay with appropriate supporting material. So one of the first and most important components of an extemporaneous speech is that it should have a thesis which informs the piece as a whole. The contestant is also expected to support the thesis drawing on reputable sources, in this case, defined as reliable printed sources of information, such as well-regarded newspapers like the New York Times, or even peer-reviewed academic journals. The speech is expected to end with a restatement of the thesis and a summary of the positions made in the speech. As should be immediately evident, extemporaneous speaking as exercised

- 108. in speech contests is radically different from Anishinaabe rhetoric as we have been discussing it here. At the top-most level, it can be seen that in making an extemporaneous speech, one is expected to construct a logical, linear, and rational argument. The material is supposed to follow one upon the other as informed by the dictates of logical, not spiritual, thinking. Thus the emphasis is on relating direct causation that is easily observable in the physical world. The argument is linear in that it is expected to follow a clear line from the beginning to the end. There is a thesis, the thesis is supported by way of evidence, and the conclusion demonstrates the manner in which the evidence has supported the thesis. The argument is rational as well. The argument is expected to stand above emotional responses and be delivered on the basis of empirical evidence. So extemporaneous speaking of this type has a clear set of foundational pillars upon which it is built. Now, it should be noted that Anishinaabe speakers can use logical, linear, and rational ways of argumentation, so it is not as if the Anishinaabeg are incapable of this type of speaking. However, as I have noted, the basis for what I am calling Anishinaabe rhetoric is informed by a separate set of considerations. I will not repeat them all here. But the importance of speaking on the basis of 鐨鑔 鑕鑞

- 111. 鑊鑉 鐅鑚 鑓鑉 鑊鑗 鐅鐺 鐓鐸 鐓鐅 鑔鑗 鑆鑕 鑕鑑 鑎鑈 鑆鑇 鑑鑊 鐅鑈 鑔鑕 鑞鑗 鑎鑌 鑍鑙 鐅鑑 鑆鑜 鐓 鐪鐧鐸鐨鐴鐅鐵鑚鑇鑑鑎鑘鑍鑎鑓鑌鐅鐟鐅鑊鐧鑔鑔鑐鐅鐨鑔鑑鑑鑊鑈鑙鑎鑔鑓 鐅鐍鐪鐧鐸鐨鐴鑍鑔鑘鑙鐎鐅鐒鐅鑕鑗鑎鑓鑙鑊鑉鐅鑔鑓鐅鐚鐔鐜鐔鐗鐕鐖鐛鐅 鐖鐕鐟鐕鐜鐅鐵鐲鐅鑛鑎鑆鐅鐺鐳鐮鐻鐅鐴鐫鐅鐷鐪鐩鐱鐦鐳鐩鐸 鐦鐳鐟鐅鐜鐚鐙鐗鐙鐞鐅鐠鐅鐬鑗鑔鑘鑘鐑鐅鐱鑆鑜鑗鑊鑓鑈鑊鐅鐼鑎鑑鑑鑎鑆 鑒鐓鐠鐅鐦鑓鑎鑘鑍鑎鑓鑆鑆鑇鑊鐅鐼鑆鑞鑘鐅鑔鑋鐅鐰鑓鑔鑜鑎鑓鑌鐅鑆鑓鑉 鐅鐧鑊鑎鑓鑌 鐦鑈鑈鑔鑚鑓鑙鐟鐅鑘鐝鐙鐗鐙鐞鐜鐞 Anishinaabe Rhetoric 189 spiritual values, on experiential experience, and from the heart

- 112. are three ways in which Anishinaabe thinking differs from extemporaneous speaking. Aside from its use as a technical term in speech contests, “extemporaneous speaking” can also mean speaking off the top of one’s head in the more popular use, that is, just saying whatever pops into one’s head. This type of speaking might also be referred to as a “stream of consciousness” style of oration. The term “stream of consciousness” is another technical term that can be found in both literature and psycholog y. Keeping in mind that I am not trying to present a detailed or complete description of the phenomenon, in psycholog y, stream of conscious refers, in essence, to the flow of thoughts in one’s mind. The use of the term in literature is similar in that in using a stream of consciousness approach, the author will represent the flow of thoughts going through a given character’s mind. Here, the feature of stream of consciousness in which I am most interested relates to what can be its disjointed nature. Thus it is not the case that thoughts flow logically from one to the other. Certainly they can. However, most usually the understanding of stream of consciousness in psycholog y and the use of stream of consciousness technique in literature is such that thoughts do not flow in a logical manner. Instead, thoughts tend to be disjointed, associative,

- 113. and random. In this regard, stream of consciousness may seem closely related to the use of digressions in Anishinaabe rhetoric. However, this is not the case. As just stated, in the stream of consciousness approach, thoughts do not necessarily adhere together, one after the other, and so can be truly random and disjointed. As argued above, it is not the case in regard to Anishinaabe rhetoric that the ideas being presented are random and disjointed. In fact, the ideas in Anishinaabe rhetoric follow an interior logic, a logic that differs from the logical, linear, rational ways of thinking preferred in Western rhetoric, but logical nonetheless. We have discussed that inner logic above, and need not repeat it here. Suffice it to say, the inner logic of Anishinaabe rhetoric is premised on spiritual values and experiential experience. It is organized in such a way as to speak as much as possible most directly to the human heart. It is not random or disjointed in the least. So we should be very careful not to confuse stream of consciousness thinking with Anishinaabe rhetoric. This is not to say one is better than the other. We just want to acknowledge that they are different. In discussing extemporaneous speaking and stream of consciousness thinking, we were examining what Anishinaabe rhetoric is not. It is not a style of speaking that seeks to replicate the standard thesis-driven argument found in Western

- 114. approaches to argumentation. It is also not simply speaking off the top of one’s head, going with the flow as it were, and following one’s stream of consciousness. 鐨鑔 鑕鑞 鑗鑎 鑌鑍 鑙鐅 � 鐅鐗 鐕鐖 鐙鐓 鐅鐷 鑔鑚 鑙鑑 鑊鑉 鑌鑊 鐓鐅 鐦鑑 鑑鐅 鑗鑎 鑌鑍 鑙鑘 鐅鑗 鑊鑘 鑊鑗 鑛鑊 鑉鐓 鐅鐲 鑆鑞 鐅鑓 鑔鑙 鐅鑇 鑊鐅 鑗鑊

- 117. Anishinaabe Ways of Knowing and Being190 The thing about extemporaneous speaking and stream of consciousness writing is that they both come out of the norms of mainstream society. They were both fashioned within and recognized as legitimate by the dominant, Western culture, and American culture as a subset of Western culture. However, there are other ways of argumentation that exist as well that do not arise out of Western ways of thinking. I would like to explore two such examples in order to demonstrate that there are other legitimate ways of speaking and presenting one’s argument. The two examples I have in mind are Japanese forms of essay writing, and African- American call and response style of speaking. The Japanese have a way of writing essays called kishôtenketsu (��䔒㎀). The Chinese characters in the term mean: start, develop, turn, end. As might be inferred, the term describes in quite literal terms the structure of the argument or presentation. Senko Maynard discusses this style of discourse in her book Japanese Communication: Language and Thought in Context.10 Using this approach, one is first expected to bring up a topic to start off the essay. Next, the writer is to develop the topic to some degree. Once having

- 118. developed the topic, the writer then puts a sudden turn or twist on the subject. Finally, the writer brings the argument to a conclusion.11 She provides the following example. Note that although Maynard includes the Japanese language versions of the sentences, I will omit them. Ki (䎧): Daughters of Itoya (the thread shop) in the Motomachi of Osaka. Shō (�): The elder daughter is sixteen, and the younger one is fifteen. Ten (䔒): Feudal Lords kill (the enemy) with bows and arrows. Ketsu (㎀): The daughters of Itoya “kill” (the men) with their eyes.12 From a Western point of view, the above argument may not appear to be well structured. There is no thesis. The “Ten” section may appear to be a digression, and the point of the argument is not introduced until the conclusion. But to a Japanese reader, this would be a perfectly acceptable manner of writing. In fact, this style of writing is so common in Japan that it can lead to some difficulties for Japanese people going to school in the United States, as illustrated by the following story. My wife is a Japanese national, and when I was a graduate student at Stanford University, she had a number of Japanese friends. One of them, who shall remain anonymous, was in a master’s program at another university in

- 119. the area. My wife asked me to help her friend edit her writing assignments. I was happy to comply. She had written a fairly extensive essay, the length of which I no longer recall. 鐨鑔 鑕鑞 鑗鑎 鑌鑍 鑙鐅 � 鐅鐗 鐕鐖 鐙鐓 鐅鐷 鑔鑚 鑙鑑 鑊鑉 鑌鑊 鐓鐅 鐦鑑 鑑鐅 鑗鑎 鑌鑍 鑙鑘 鐅鑗 鑊鑘 鑊鑗 鑛鑊 鑉鐓 鐅鐲 鑆鑞 鐅鑓 鑔鑙 鐅鑇 鑊鐅