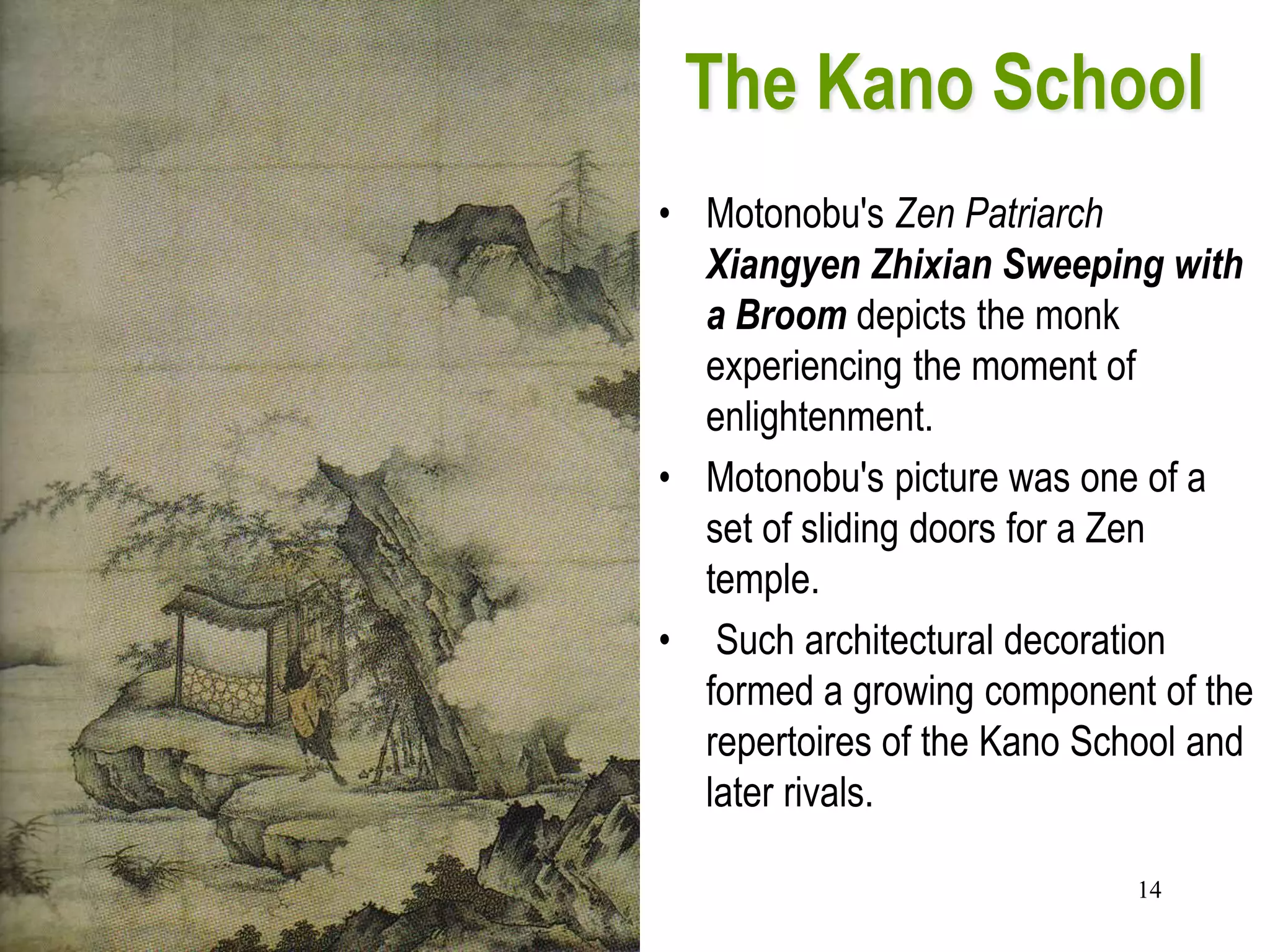

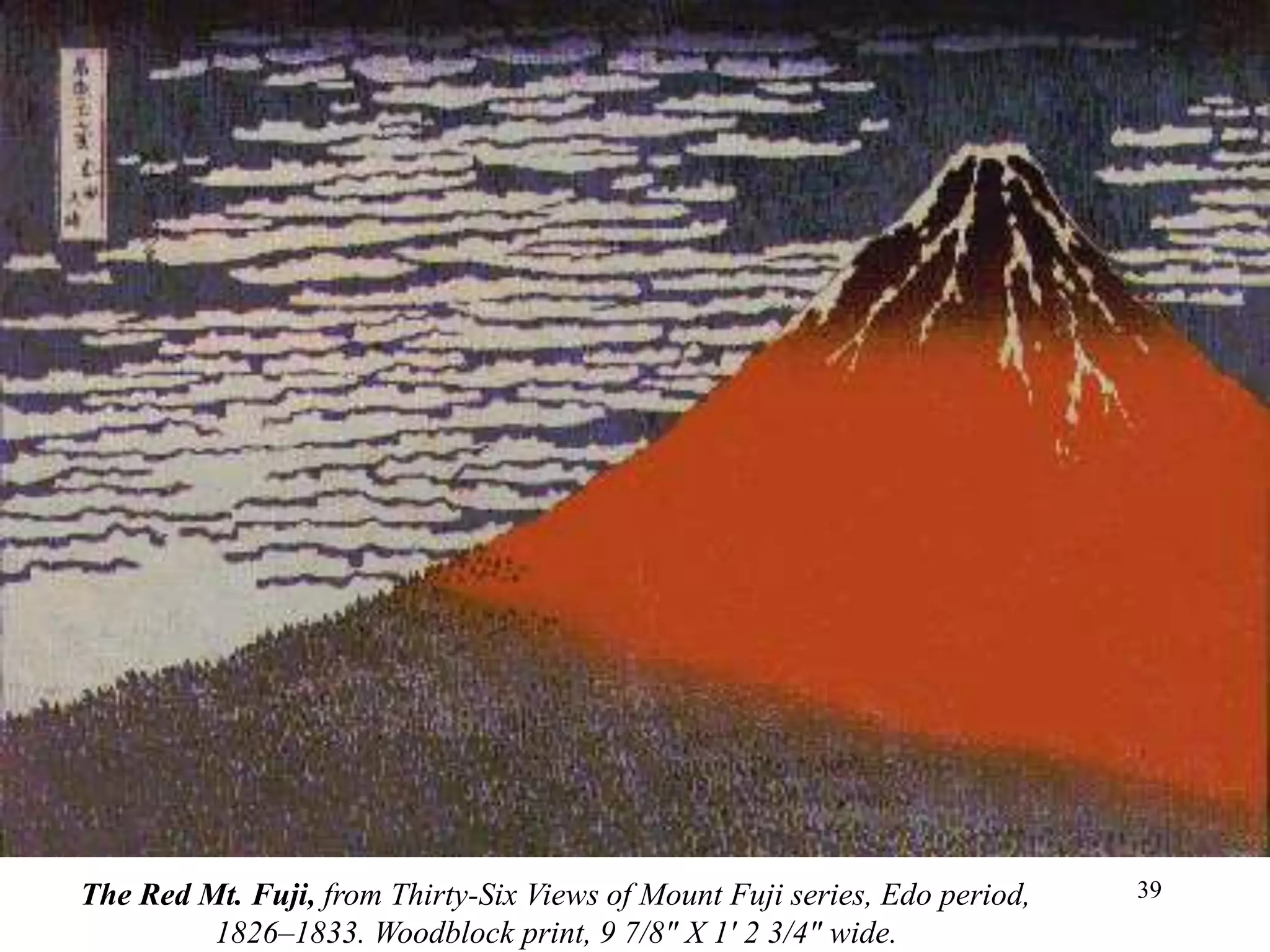

1. The document summarizes Japanese art from the 1336-1868 period, covering major styles and movements including feudal Japan under the Ashikaga shogunate, Zen Buddhism, Muromachi period gardens and ink painting, Momoyama period tea ceremonies and architecture, Edo period Kano school painting and ukiyo-e prints.

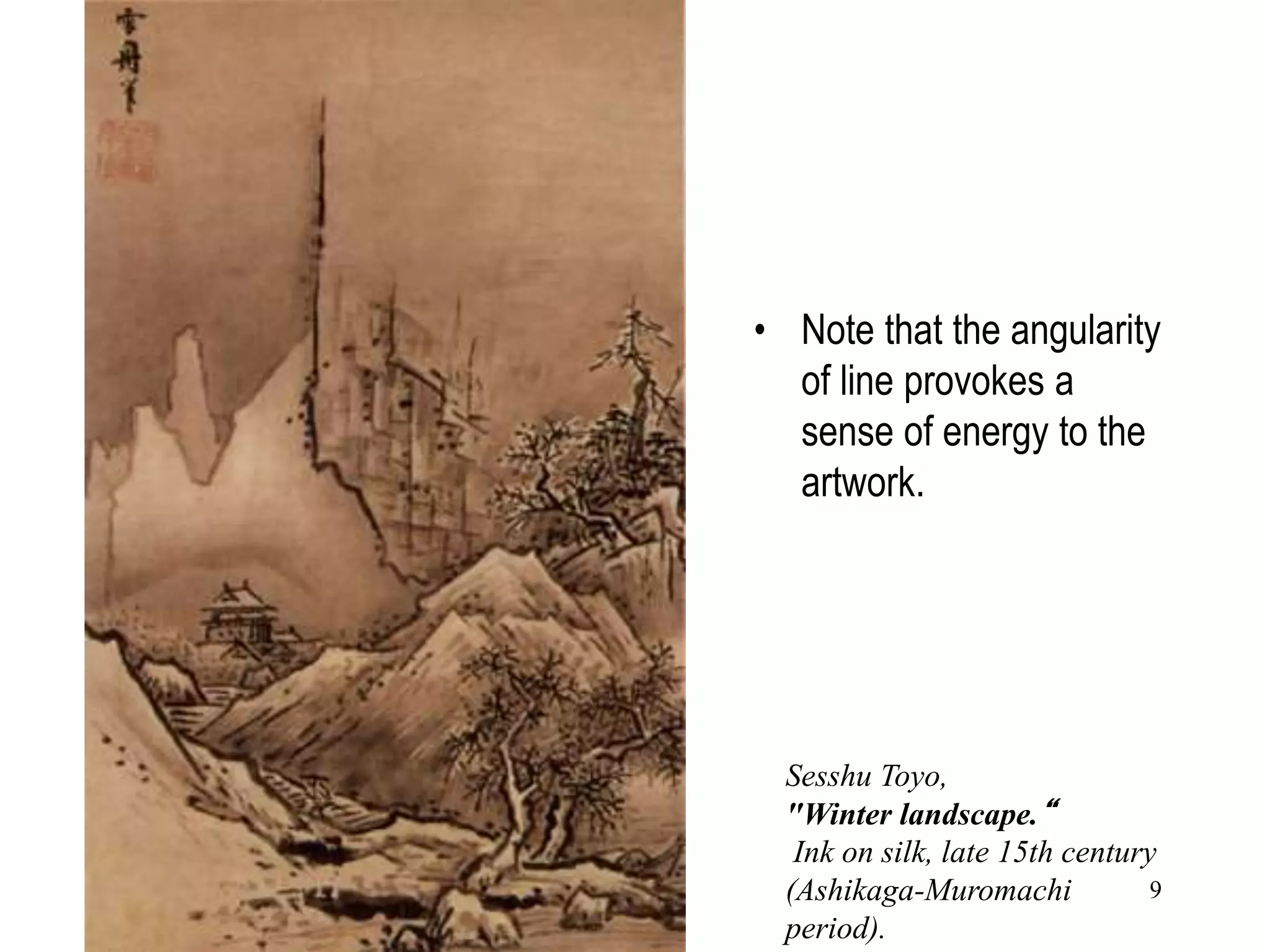

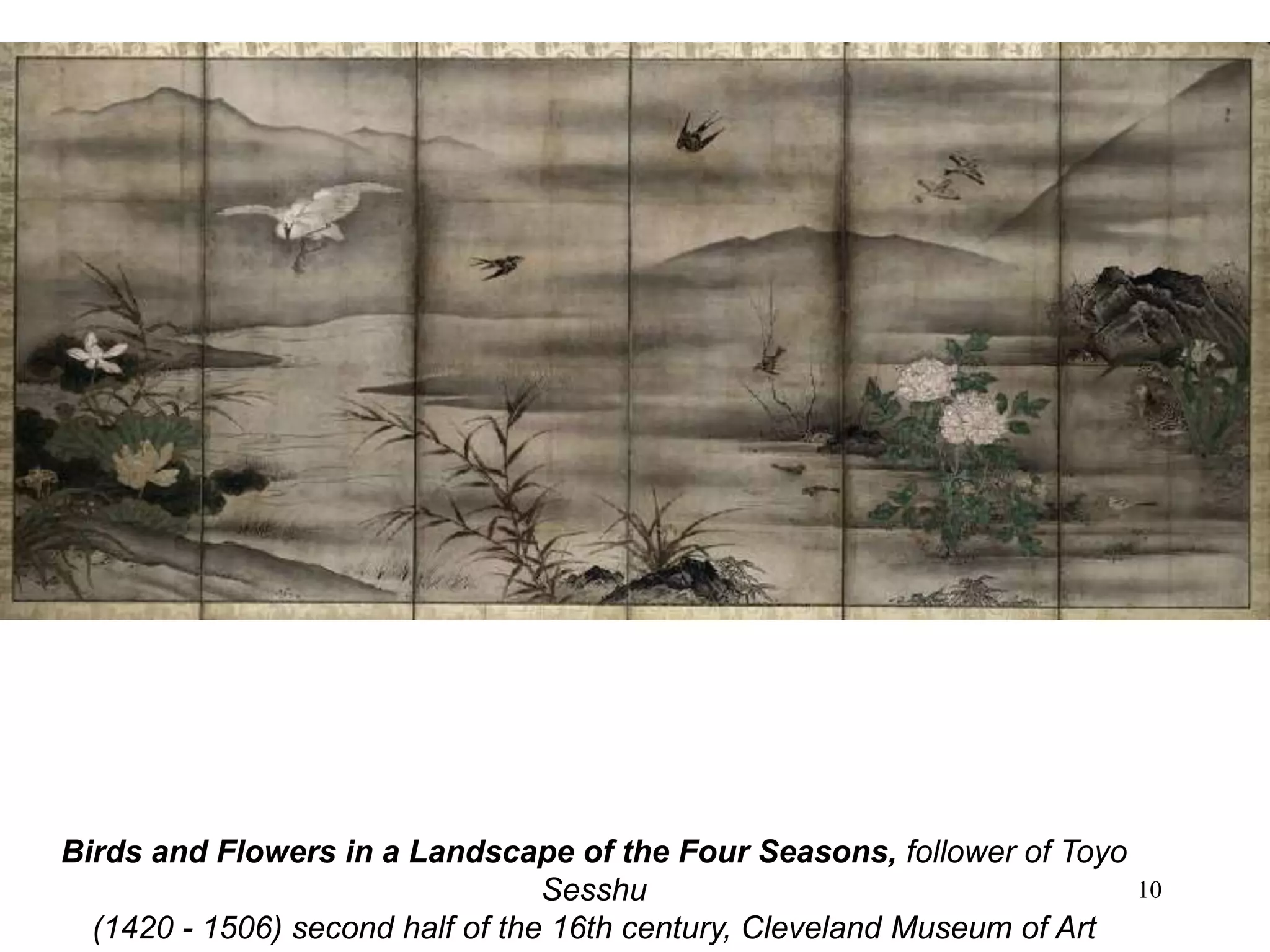

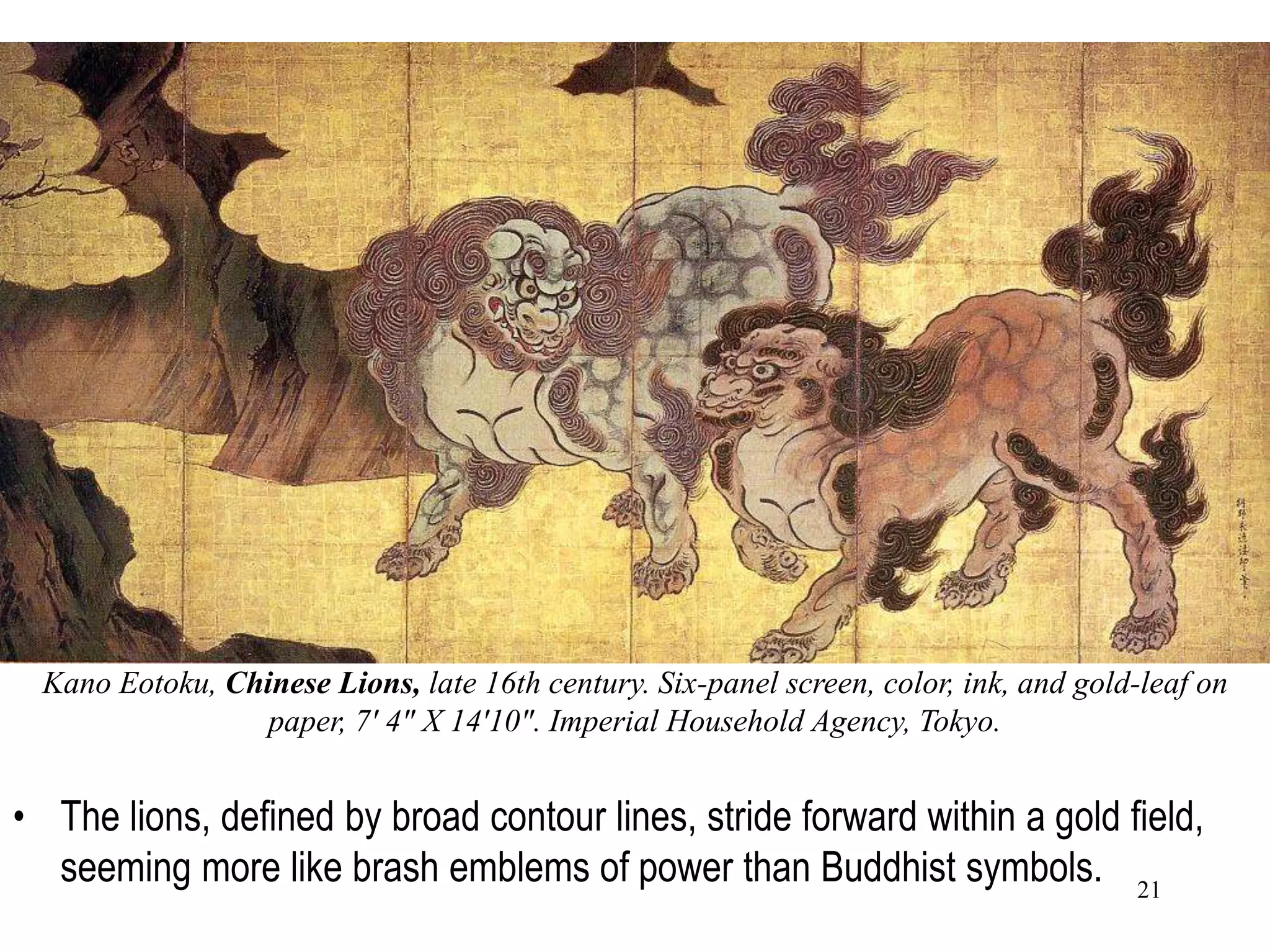

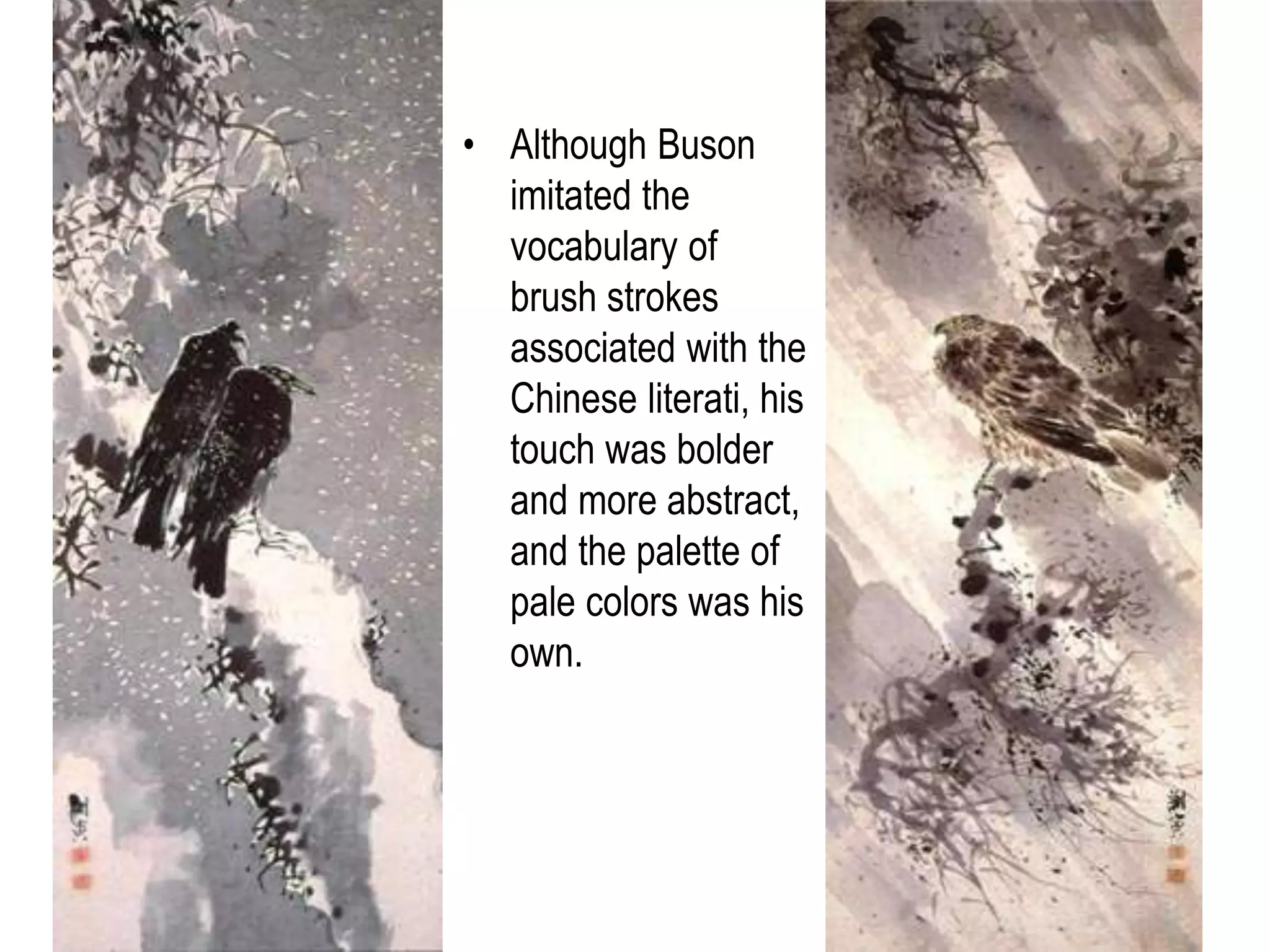

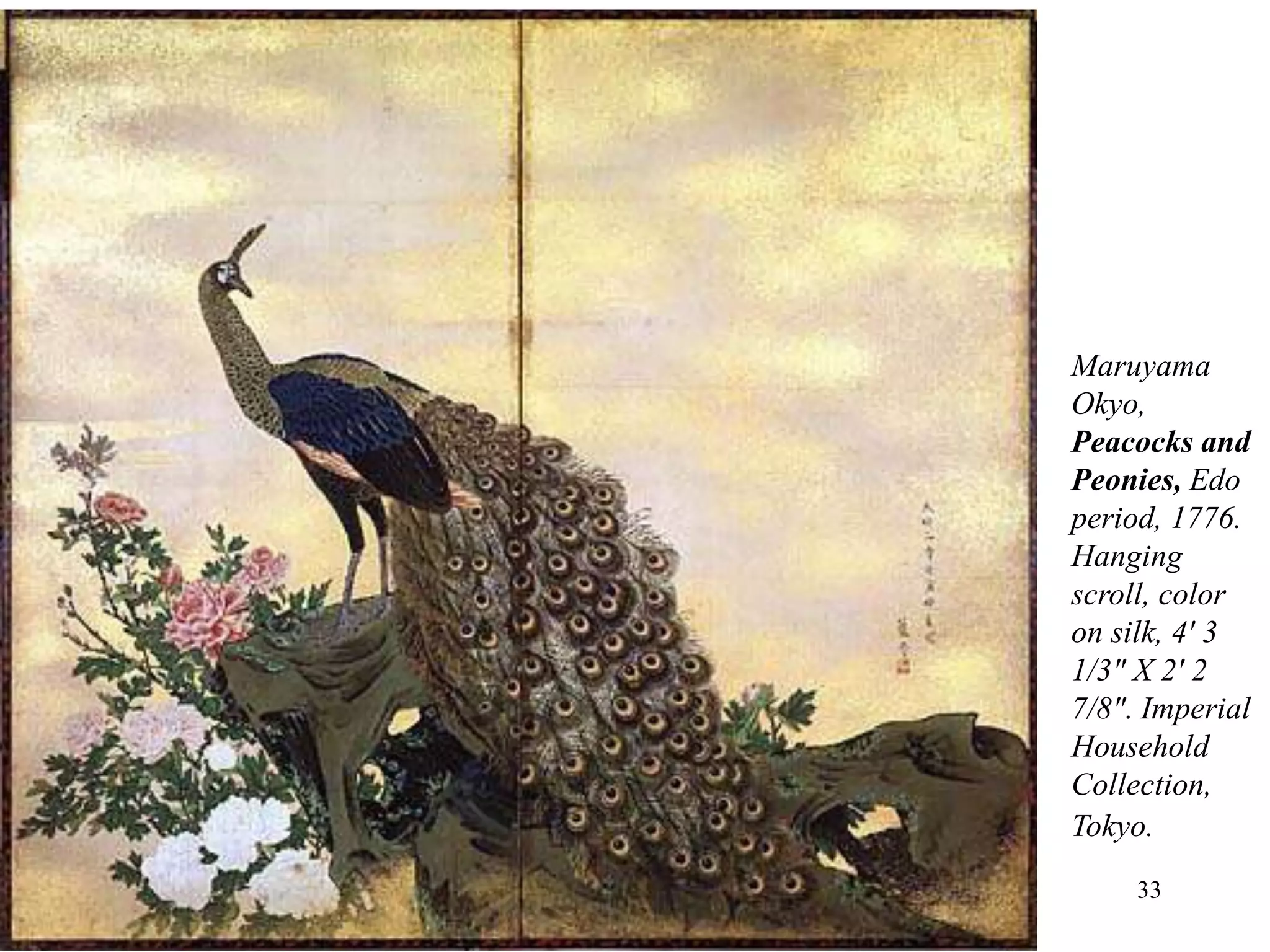

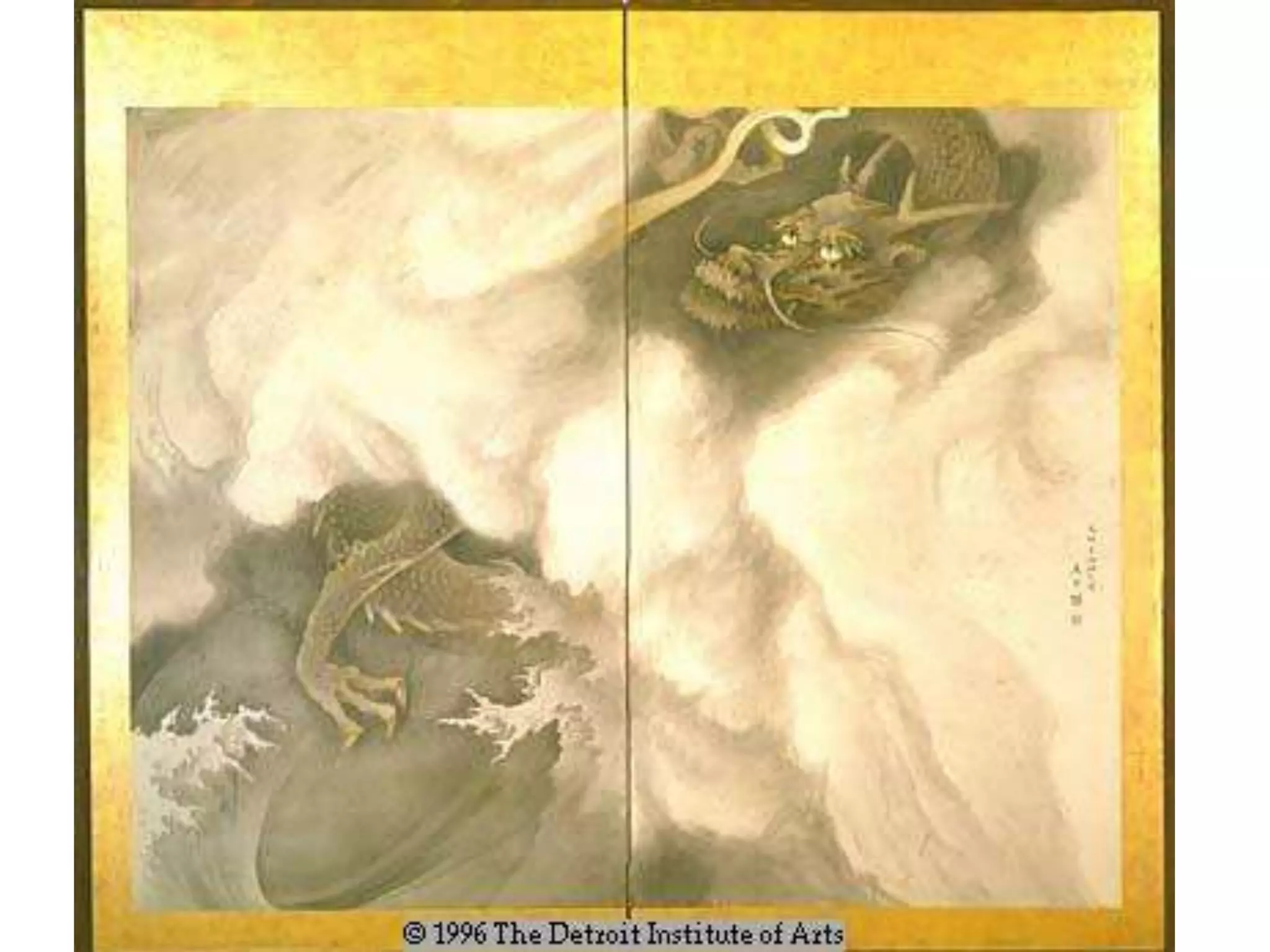

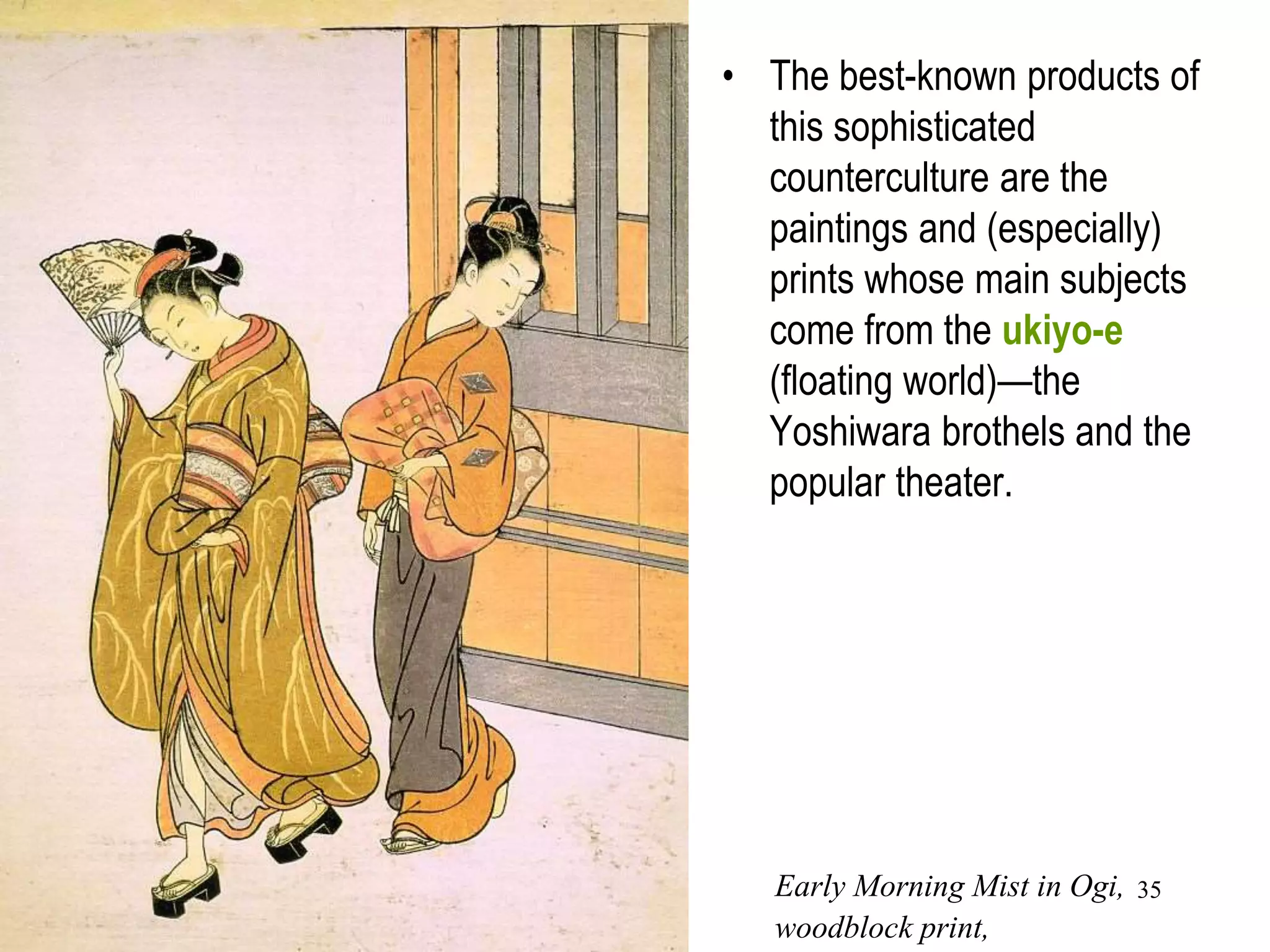

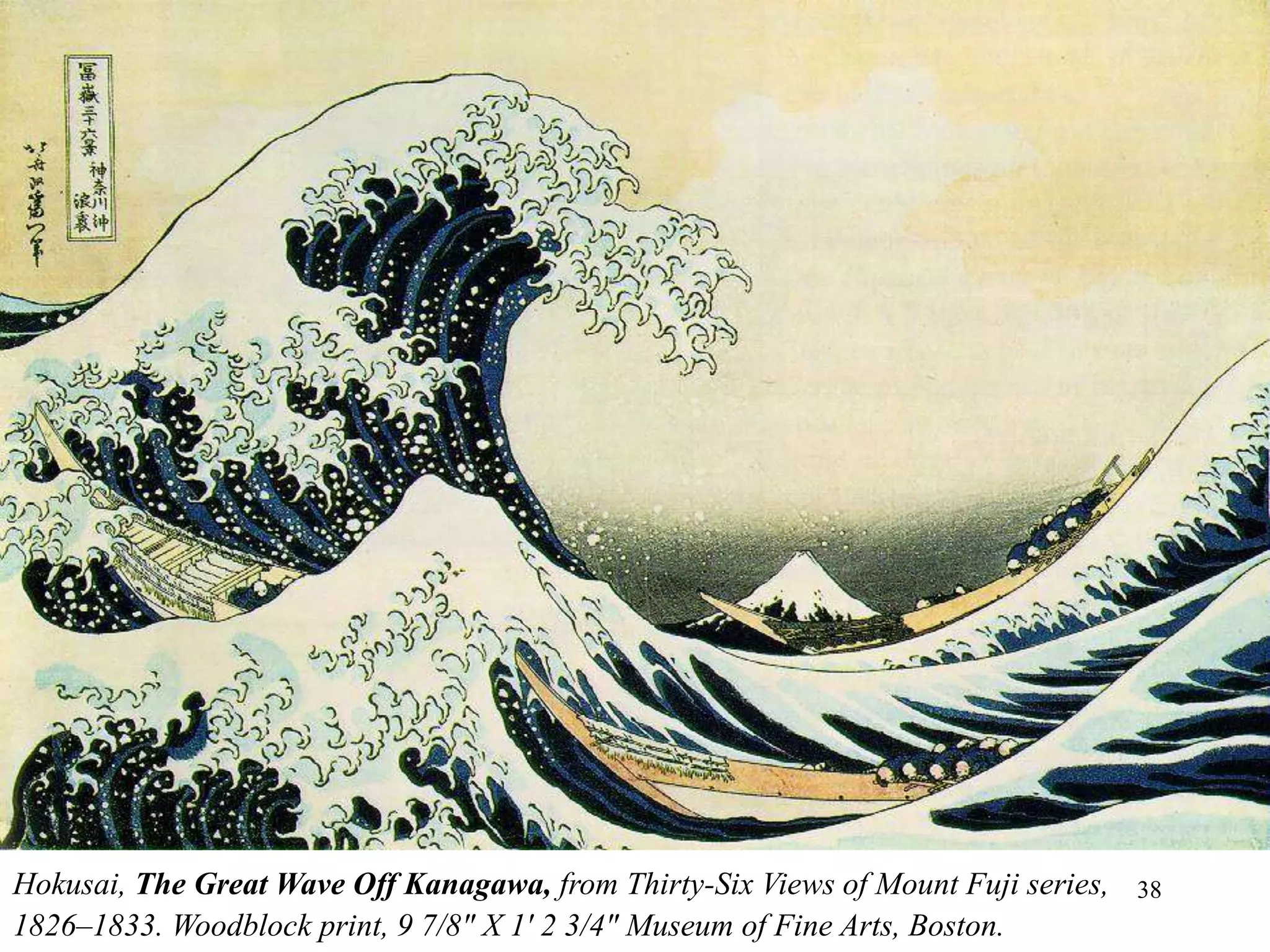

2. Key artists mentioned include Sesshu Toyo, Hasegawa Tohaku, Tosa Mitsunobu, Kano Eitoku, Honami Koetsu, Tawaraya Sotatsu, Ogata Korin, Yosa Buson, Maruyama Okyo, Suzuki Harunobu, and