This book provides a global perspective on water sustainability issues. It begins with an introduction noting the looming global water crisis and rising demand for water resources. The book is divided into three parts. Part 1 discusses current status and challenges related to water, including rising demand, water and poverty, governance and financing, pollution and health issues, conflicts over water resources, and the impacts of climate change. Part 2 examines nature's water resources including the water cycle and shrinking freshwater stores. Part 3 considers approaches toward achieving sustainability, such as reducing demand, increasing supplies, improving water quality, managing seawater and weather, and improving monitoring, management or aid to developing nations. The book concludes by assessing whether global water sustainability is achievable.

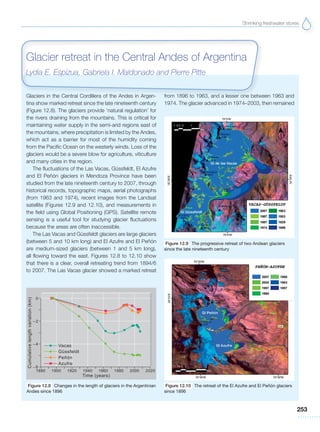

![Water Sustainability

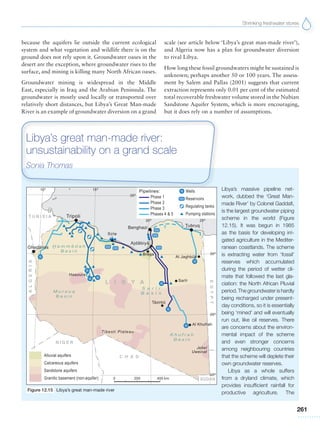

56

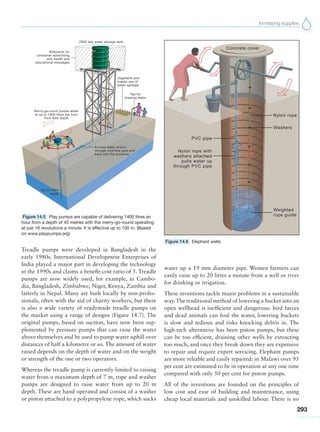

(Moriarty, 1988). However, birds that eat fish from the

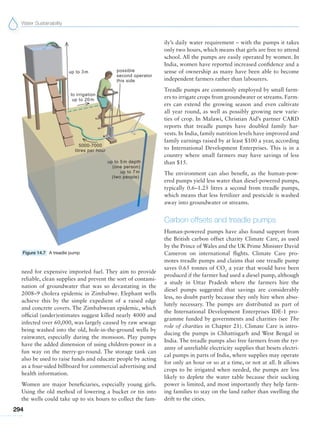

lake showed levels of 1600 ppb in their fatty tissues.

Endocrine disrupters – a

sea of oestrogens

Research over the last two decades has revealed the dan-

gers of many man-made substances now in common

use that act as ‘endocrine disputers’, causing the body’s

endocrine or hormone release system to malfunction.

These compounds affect the sexual development of ani-

mals and humans and they tend to bio-accumulate in the

body. Endocrine disrupters may either act like female sex

hormones, mimicking oestrogens; they may block the

normal receptors for the sex hormones, effectively turn-

ing off the hormonal activity; or they might activate the

receptors in a different way, perhaps stimulating some

activity.

Many everyday products act as endocrine disrupters,

either in their original state or in the secondary sub-

stances they produce as they degrade. They are by no

means restricted to agricultural use, although it was pes-

ticides that first alerted biologists to the dangers. The

problem chemicals include many chlorinated hydro-

carbons, DDT and its breakdown product DDE, DES

(diethyl stilbestrol), some PCBs, parabens used in cos-

metics, dioxins, several pesticides such as atrazine, and

fungicides. Many of these substances are resistant to

biodegradation. But some substances that are non-toxic

or have low toxicity may nevertheless break down into

other substances in the environment that are unstable

and more toxic. Members of one major class of plas-

ticizer, called phthalates, used for example to make

plastics flexible and to improve the flow of paints, are

known to be endocrine disrupters in animals.

Although research in the early 1990s first alerted medi-

cal and environmental science to the dangers, manu-

facturers have mounted strong opposition to legislative

controls. Only now are governments beginning to intro-

duce controls, more than a decade since expert scientists

presented their findings to the US Congress and called

for legislation. Around 200 million tonnes of plasticizers

are produced in North America annually. The American

Chemistry Council – which represents the industry and

is not as might appear a scientific organization – claims

that there is no sound evidence that these chemicals

affect the endocrine system and points out that they play

many valuable roles, including producing flexible tubing

for medicine and coatings for pills.

The International Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS),

run by the WHO, the International Labour Organiza-

tion and UNEP, was asked to investigate the claims and

present evidence to the contrary (Damstra et al, 2002).

There is very strong evidence for effects on wildlife, even

though the exact mechanisms are often poorly under-

stood. The evidence for effects on humans is less clear,

partly because obtaining experimental evidence with

humans is more difficult than with laboratory-control-

led experiments on animals. Even so, strong statistical

evidence was produced in the early 1990s for effects

on humans as well as animals. Sharpe and Skakkebaek

(1993) and Dibb (1995) stated that at least 37 differ-

ent chemicals had been identified that disrupt hormone

operations and appear to be linked to testicular cancer

and other sexual abnormalities in humans and animals.

The IPCS report concluded that although the evidence

for effects on humans in ‘weak’, this only means that

more rigorous studies are urgently needed. Recently,

Swan et al (2005) published meticulous research that

establishes a link between genital abnormalities in boys

and their prenatal exposure to phthalates as measured in

the mother’s urine.

‘Despite an overall lack of knowledge

of mechanisms of action of EDCs

[endocrine-disrupting chemicals], there are

several examples where the mechanism

of action is clearly related to direct

perturbations of endocrine function … The

evidence that high-level exposure may

impact both humans and wildlife indicates

that this potential mechanism of toxicity

warrants our attention.’

WHO/ILO/UNEP International Programme on Chemical

Safety, Damstra et al (2002)

Research in the Great Lakes in the 1990s revealed major

problems with the development of fish in Lake Erie

(exploding thyroids and trans-sexual development) even

though the lakes have been largely cleaned up. Scien-

tists recently identified the ‘Great Lakes Embryo Mor-

tality, Edema (or oedema) and Deformity Syndrome’

among fish-eating birds, which has been directly related

to PCBs. At the 2009 Annual Conference on Great

Lakes Research held in Toledo, Ohio, Parrott and col-

leagues from Environment Canada presented evidence

of a link between the synthetic oestrogen used in birth](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/watertextbook-130918222901-phpapp02/85/Water-textbook-69-320.jpg)

![Pollution and water-related disease

79

appears to imply a major effect on the environment

due to increased human influence, most likely related to

modern water management. In the Indian subcontinent,

the problem was exacerbated by three factors which led

to a dramatic increase in the use of groundwater as a

supposedly safer source of drinking water and a major

resource for expanding irrigated agriculture: 1) the

worsening biological contamination of surface waters in

the mid-twentieth century; 2) the Green Revolution in

agriculture; and 3) the severe cholera outbreak in south

Bengal in the 1960s. The World Bank was a principal

promoter of the switch to groundwater and funded

thousands of tubewells for irrigation from the 1960s

onwards.

Arsenic may be released by oxidation of pyrite, arse-

nopyrite and clay minerals, which have arsenic

adsorbed on their surface. Oxygen enters aquifers when

the water table is lowered; the arsenic is then free to

pollute the groundwater when the rocks are reflooded.

Arsenic pollution may thus result from groundwater

overdraft.

It has even been suggested that reducing surface water

discharges can have a similar effect: diversion of the

Ganges, the Tisha and 28 other transboundary rivers in

India may have contributed to the problem in Bangla-

desh by reducing groundwater recharge. Even though

millions of tubewells were installed in Bangladesh before

the 1970s, medical records only show a significant rise in

pathological symptoms during the 1980s in West Bengal

and 1990s in Bangladesh. Some observers have linked

this with the completion of the Farraka barrage in 1975,

which diverted Ganges water to Calcutta and reduced

the discharge entering Bangladesh.

A second hypothesis focuses on the opposite situation:

excess water. In organic-rich clayey sediments, satu-

rated, anaerobic conditions create a chemically reduc-

ing environment, which leads to the dissolution of iron

oxyhydroxides containing sorbed arsenic. Iron-reducing

bacteria may also play a part. This situation is typical

of natural wetlands and could also be a dangerous by-

product of over-irrigation.

Yet a third hypothesis blames pollution from human

sources, especially from agriculture. Nitrate from ferti-

lizer can oxidize sulphate minerals and release sorbed

arsenic. And arsenical pesticides were widely used in

America for 100 years until banned in the late twenti-

eth century, although their low solubility suggests that

they are not a major source of water pollution. Cur-

rent research in Botswana’s Okavango delta is trying

to determine whether the calamitous arsenic pollution

that has affected the town of Maun is due to exces-

sive drawdown of the water table or human sewage

(Huntsman-Mapila et al, 2006, in press).

Solutions

In recent years, some communities in the Bengal basin

have begun to revert to using surface waters as the

enormity of the problem has been realized. Yet, ironi-

cally, low-cost technology is already available for

purifying well-water in the domestic environment.

One method is to mix the water with ferric chloride

and potassium permanganate to oxidize it in a plas-

tic bucket and strain it through a cloth into a second

bucket filled with sand to clarify it. Results reported

to the United Nations University show arsenic concen-

trations reduced to less than 20 μg/L, even with water

containing up to 500 μg/L (Ali et al, 2001). Many other

sorbents can be used, especially laterite, a clay soil rich

in iron and aluminium, providentially common in trop-

ical regions. Education and government help are the

keys to encouraging adoption.

‘Reversion to surface water-based supply

… will involve enormous financial outlay

and would nullify the investment of around

Rs 10,000 crores [100 billion rupees or

around $2 billion] already made in West

Bengal alone over the last 30 years. It

is necessary that such major policy shift

should not be ad hoc, but a science-

driven decision.’

S.K. Acharyya, former Director General

in the Geological Survey of India, 2002

Better still would be expansion of the public water

supply systems in which filtration and coagulation meth-

ods are applied centrally. However, the best solution is to

identify the specific causes responsible in each area and

either to manage water usage appropriately or else to

clean up at source. Considerable research effort is cur-

rently being devoted to this end, especially in India and

Bangladesh. One promising approach is bio-remediation

within the aquifer, introducing microbes to precipitate

iron sulphide that will sorb arsenic.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/watertextbook-130918222901-phpapp02/85/Water-textbook-92-320.jpg)

![Water Sustainability

166

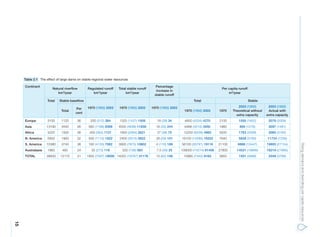

some average values. In general, water consumption is

greater in drier climates. The latest crop calculations

take into consideration the differences in the water

requirements for similar products produced in different

environments using the FAO’s CROPWAT program to

calculate crop water requirements and FAO statistics on

yields and world trade (Hoekstra and Hung, 2005).

The team have also developed the idea of a ‘water

footprint’, which is the total amount of water used in

the production of goods and services (Chapagain and

Hoekstra, 2004). This can be applied nationally or for

individual producers. Warner (2003) argues that it could

usefully be applied to individual regions or river basins

as well. The national water footprint can be divided

between internal or domestic and external or interna-

tional trade footprints. The concept is analogous to

the carbon footprint calculations being introduced as

part of the fight against greenhouse gas emissions. The

team provide short instructional courses in the method

and have recently produced a Water Footprint Manual

for use by individuals and companies. The article ‘The

globalization of water’ by Arjen Hoekstra, later in this

chapter, summarizes the concept and its implications.

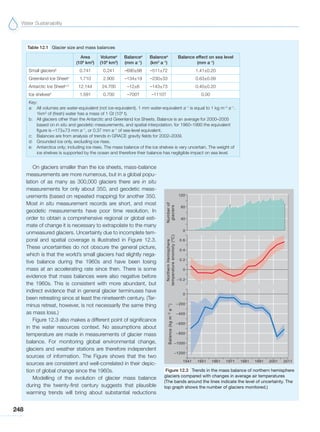

The water footprint concept reveals the wide differences

in consumption around the world and also the extent

to which consumption in one nation has an impact on

the water resources of another. While the average world

citizen consumes around 1240 m3

a year through drink-

ing, washing, food and other goods, Americans consume

twice as much and Chinese presently consume a little

over half as much, although this is rising rapidly (Figure

8.10). In more everyday terms, people in America con-

sume over 6000 litres of virtual water daily, compared

with less than 2000 in China.

World trade means that all countries are to some degree

dependent on others. Consumers of imported goods in

Europe, Japan and the USA have impacts, sometimes

serious ones, on water resources in the developing world

and emerging economies, especially in Latin America,

where Brazil and Argentina are major exporters. Africa

is a net exporter, particularly to Europe, yet much of

the continent suffers water shortages and more people

are starving in Africa than on any other continent (see

Róisín Murray-William’s article ‘Valentine flowers from

Kenya – a perverse trade?’, later in this chapter). The

USA, Canada and Australia are also major exporters,

but their domestic resources can generally sustain the

trade with backing from reciprocal imports.

Table 8.1 Virtual water needed to produce some common

products

Product Litres of water

Manufactured goods

Car (steel only in average car) 32,000

Microchips 1 kg

(for cleaning during production)

16,000

Bio-diesel 1 litre (from soybean) 14,000

Leather shoes – pair 8,000

Cotton T-shirt 4,000

Bio-ethanol (sugar beet [lowest] to sugar cane

and maize [greatest])

1,400–2,600

Synthetic rubber 1 kg 460

Copper 1 kg 440

Steel 1 kg 260

Plastic 1 kg 41

Cereals, fruit and vegetables

Bananas 1 kg 850

Rice 1 kg 3,400

Sugar (cane) 1 kg 1,500

Wheat 1 kg 1,350

Maize 1 kg 900

Apples/pears 1 kg (single 100g = 70 litres) 700

Cabbage 1 kg 200

Potatoes 1kg 160–250

Tomatoes 1 kg (single 70 g = 13 litres) 180

Lettuce 1 kg 130

Animal products

Beef 1 kg 15,500

Pork 1 kg 4,800

Eggs 1 kg (single 60 g = 200 litres) 3,330–4,700

Chicken 1 kg 3,900

Processed food

Chocolate 1 kg 24,000

Hamburgers 1 kg (single 150 g = 2400 litres) 16,000

Cheese 1 kg 5,000

Bread (from wheat) 1 kg 1,300

Drinks

Coffee, large 250 mL cup

(to grow, package and ship the coffee)

280

Milk 250 mL glass 250

Orange juice 250 mL glass 210–250

Wine 250 mL glass 240

Apple juice 250 mL glass 240

Beer (from barley) 250 mL glass 75

Tea 250 mL cup 30

Bottled water 250 mL (processing and plastic) 0.75–1

Sources: Hoekstra and Chapagain (2008); Rijssenbeek (2007); Gleick (1993);

www.h20conserve.org](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/watertextbook-130918222901-phpapp02/85/Water-textbook-179-320.jpg)

![Water, war and terrorism

183

They may have a philosophy or simply a grudge. Devis-

ing effective counter-measures is complicated by the

fact that the impacts may not be immediate. Immediate

impacts might be spectacular, but long-term fallout, for

example, continuing to affect public health could be a

greater threat: anthrax could cause widespread deaths

and persist for years.

Following 9/11, many US water companies immedi-

ately began to remove potentially sensitive information

from their websites and Congress set up a Directorate of

Homeland Security to oversee protective measures. Fol-

lowing the discovery of a computer in Afghanistan con-

taining structural analysis programs for dams, the FBI’s

National Infrastructure Protection Center issued a bulle-

tin in 2002 warning of‘Terrorist Interest in Water Supply

and SCADA [Supervisory Control And Data Acquisi-

tion] Systems’ (Shea, 2003). The National Infrastructure

Protection Center now sends warning messages to the

Association of Metropolitan Water Agencies’ Informa-

tion Sharing and Analysis Center (ISAC). ISAC then

delivers early-warnings to water officials throughout the

country.

One ineluctable geographical problem is the extreme

concentration of possible targets: just 15 per cent of

all large drinking water and sewage plants in the USA

supply more than 75 per cent of the population. There

are big hydropower plants as well. The Grand Coulee

Dam on the Columbia River alone produces 25 per cent

of US hydropower. The Hoover Dam on the Colorado

River provides seven per cent of all public electricity in

the west USA. A bypass was completed in 2007 to divert

traffic away from the Hoover Dam and public tours

inside the dam have been stopped – as they have in many

dams in the USA, Britain and elsewhere.

Although these represent the largest targets and would

cause maximum disruption, they will be best protected.

On the other hand, there are hundreds of smaller water

targets that could be less protected. They would not

have the same physical effect, but they could have a dis-

proportionately high scare effect.

The task of providing effective protection is complicated

by the very large range of possible aims and methods of

attack: whether toxins are chemical, biological or radio-

logical; where and how the toxins might be introduced

into water systems; whether the terrorists’ aim is to kill,

infect or simply create fear and panic; whether the aim

is to poison or to physically disrupt the water supply

system by breaching pipelines to cut off supplies or by

breaching dams to cause a flood; whether the attack is

physical or cyber; or whether the attack is indeed aimed

at the water system itself or just using the distribution

network to attack other buildings, as in the possible case

of using sewers to plant bombs beneath key buildings.

Sewage plants and sewer networks are also theoretical

targets. Such attacks may not be so spectacular, but they

could lead to widespread infection.

The list of vulnerable activities also extends well beyond

municipal drinking water supplies. It includes bottled

water production and food and beverage manufac-

ture. Companies using their own private water sources

could be especially vulnerable to commercial terrorism:

the recall of thousands of bottles of Perrier Water after

some were found to contain traces of benzene in 1990

illustrates the potential commercial damage that can be

done, whether this is intentional or accidental. In that

particular case, Perrier attributed the problem to filters

designed to remove the natural benzene that had not

been renewed.

Prevention of waterborne disease has been hindered by

ageing infrastructure and outmoded analysers in many

water plants.The USA Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA) established a water protection task force in 2001,

charged with helping federal, state and local partners

to improve protection of drinking water supplies from

terrorist attack. And the EPA’s National Homeland

Security Research Center initiated the Environmental

Technology Verification (ETV) programme to examine

rapid screening tests that could detect water terrorist

acts as early as possible. The ETV study shows that the

Aqua Survey IQ-Tox Test™ performed extremely well

for the detection of toxic agents or ‘threat contaminants’

in drinking water. The tests focus on both chemical and

biological toxins, such as aldicarb, colchicine, cyanide,

dicrotophos, thallium sulphate, Botulinum toxin, ricin,

soman and VX. Britain has also spent tens of thousands

of pounds on improving the security of water systems,

and the Severn Trent Eclox system performed well in

EPA tests. The international Bentley Institute is market-

ing a wide range of software to help design more secure

water systems, including WaterCAD, WaterGEMS and

WaterSAFE™, offering a full detection, prediction and

response system developed by Haestad. Starodub (2009)

gives a detailed up-to-date review of progress with

instrumental systems to detect threat contaminants in

water. He notes that despite the 1972 Biological Weap-

ons Convention, many countries continue to produce

agents of biological warfare, ranging from biochemical](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/watertextbook-130918222901-phpapp02/85/Water-textbook-196-320.jpg)