RSHUM 806Literature Review Grading RubricStudent Criteria.docx

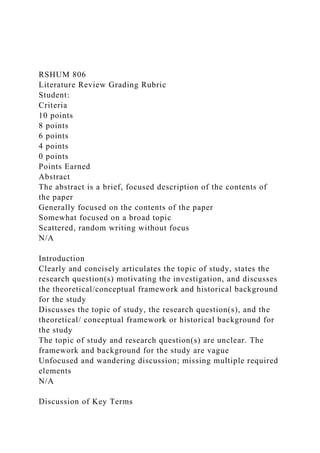

- 1. RSHUM 806 Literature Review Grading Rubric Student: Criteria 10 points 8 points 6 points 4 points 0 points Points Earned Abstract The abstract is a brief, focused description of the contents of the paper Generally focused on the contents of the paper Somewhat focused on a broad topic Scattered, random writing without focus N/A Introduction Clearly and concisely articulates the topic of study, states the research question(s) motivating the investigation, and discusses the theoretical/conceptual framework and historical background for the study Discusses the topic of study, the research question(s), and the theoretical/ conceptual framework or historical background for the study The topic of study and research question(s) are unclear. The framework and background for the study are vague Unfocused and wandering discussion; missing multiple required elements N/A Discussion of Key Terms

- 2. Keywords and essential terms are clearly discussed and defined using direct support from authoritative sources on the topic; includes citations Keywords and essential terms are clearly discussed and defined Definitions of keywords and essential terms are ambiguous or vague Missing multiple required elements N/A 40 points 30 points 20 points 10 points 0 points Review of the Literature Relevant research findings are tightly synthesized and organized by themes/categories; uses a balanced amount of direct quotation; includes citations to support findings Research findings are organized by themes/categories; uses direct quotations and includes citations to support findings Research findings are summarized by study, rather than synthesized by themes/categories; direct quotations are used either too heavily or too sparingly Fails to include relevant research or includes findings unrelated to the topic; sources of argumentation and support unclear N/A 10 points 8 points 6 points 4 points 0 points

- 3. Summary/ Conclusion Includes a focused summary of key findings from the review; gaps in the literature and recommendations for future research are clearly discussed Includes a summary of key findings from the review; gaps in the literature and recommendations for future research are identified Summary of key findings is unfocused or inconsistent with the review; gaps in the literature or recommendations for future research are vague Unfocused and wandering summary; missing multiple required elements N/A Grammar, Usage, & Mechanics 0–2 errors 3–4 errors 5 errors 6–8 errors More than 8 errors APA Format 0–2 APA errors 3–5 APA errors 6–7 APA errors 8–9 APA errors More than 10 APA errors Total: Instructor Comments: Gradaute Rearch Course Dr. Arbelo

- 4. Writing Guide for the Literature Review I. Prewriting involves the preparation and arrangement of your ideas before writing them into a paper. Use whatever techniques work for you (e.g.–Freewriting, Brainstorming, Listing, Outlining, Questioning, Clustering). Your research and documentation are accomplished during the prewriting stage. A. Sources 1. Generate material from outside sources. You must use at minimum 10 outside sources for your literature review. These sources MUST be credible, quality academic sources that are limited to: peer reviewed journal articles (mostly), textbooks, government websites. 2. Peer-reviewed sources are preferred (journals and books published at university presses). You can find such sources through Liberty’s online library. The Library Research Portal there will help you find scholarly journals. Note that the top database used for education subjects is ERIC. 3. Because this research assignment has many possible facets you can explore, you may have a valid reason for using a non- peer reviewed sources. Exceptions include the following: a. Online databases of historical texts/documents (where the sponsoring organization, editorial board, and information about the original printed source are clearly identified) b. Professional organizations (usually ending in a .org suffix) c. Government agencies (ending in a .gov suffix) d. Websites with the “.edu” extension are not necessarily reliable ones as many different people have access to posting articles on such sites. Additionally, faculty material published on such sites have not been subject to the rigorous review process required by print publications (Just because someone has the degree doesn’t mean his/her entire body of work is recognized by the academic discipline in which he/she operates). B. Research

- 5. a. Go through your sources and take notes on information relavent to your topic. b. Be creative & original in selecting information. c. Once you’ve discovered your purpose for writing, that purpose will inform the rest of your note taking. d. Document! When you’re getting ideas from outside sources, you must take special pains to identify that material as such, so record all bibliographical information and make note of the page source of every quotation you retrieve. Doing this now, at the prewriting stage, will save you much grief later on. II. Thesis Statement: For this assignment, you should have already written your thesis statement. III. Outline and write your literature review. The way you synthesize material is unique to you. Your arrangement of various points can be original. Your own interpretations and ideas can be incorporated. Look for gaps in your sources: there may be a point that is not stressed or an obvious conclusion that is overlooked. Dispute with your sources. Remember to stay in line with your Research Proposal as well as the guidelines provided by the Writing the Winning Dissertation textbook. IV. Revise, Edit, and Proofread A. Check your thesis statement. Does it clearly articulate all the points you’ve covered in your review? Are any points mentioned that aren’t covered in your review? B. Check your body paragraphs against your thesis (12 page review). Are they related to your thesis? Are they analytical? C. Check the details of your body paragraphs. Do you have enough support for your topic sentence? Are all the details in each body paragraph directly related to their respective topic sentence? Are the points you’re making arranged in such a way

- 6. that your reader can clearly follow your line of thinking? Do you have too much outside support (so much so that it overwhelms your voice)? D. Read your paper carefully (out loud is suggested). E. Check your compliance with APA format. Review in-text documentation and works cited page (using APA Handbook to do so). Check for any missing citations; fix if necessary. V. Submit the final draft of your paper by the deadline stated (12 page literature review, not including the cover page or reference page). FOLLOW THIS LAYOUT: Introduction, Conceptual Framework, Review of the Reseach Literature, Summary and Future Research Introduction A sound literature review is an extremely important component of many types of papers written in graduate school. Professional journals across disciplines typically require authors to include a literature review in articles that are submitted for consideration for publication. Students are asked to include a literature review in theses and dissertations, as well as papers across graduate school courses. Writing a properly structured literature review is a very important skill at the graduate level. A literature review (also expressed as “a review of the literature”) is an overview of previous research on the graduate student’s topic. It identifies and describes and sometimes analyzes related research that has already been done and critically summarizes the state of knowledge about the topic. To best understand the role of a literature review, consider its place in the research process and in the research paper.

- 7. The research process often begins with a question that the researcher would like to answer. In order to identify what other research has addressed this question and to find out what is already known about it, the researcher will conduct a literature review. This entails examining scholarly books and journal articles, and sometimes additional resources such as conference proceedings and dissertations, to learn about previous research related to the question. Researchers want to be able to identify what is already known about the question and to build upon existing knowledge. Familiarity with previous research also helps graduate students understand a topic in an in depth manner and it also helps researchers design their own study Literature review should include: Abstract – no more than 150 words properly formatted A. Introduction to the Literature Review B. Conceptual Framework C. Review of Research Literature D. F. Summary and FutureResearch The Objectives of a Literature Review Authors should try to accomplish the following four important objectives in preparing a literature review: 1. The review should provide a thorough overview of previous research on the topic. This should be a helpful review for readers who are already familiar with the topic and an essential background for readers who are new to the topic. The review should provide a clear sense about how the author’s current research fits into the broader understanding of the topic. When

- 8. the reader completes reading of the literature review, she or he should be able to say, “I now know what previous research has learned about this topic.” 2. The review should contain references to important previous studies related to the research question that are found in high quality sources such as scholarly books and journals. A good literature review conveys to readers that the author has been conscientious in examining previous research and that the author’s research builds on what is already known. In this process, highly interested readers are also provided with a set of references that they may wish to read themselves. 3. The review should be succinct and well-organized. Most literature reviews range from 30 to 80 pages. In this assignment, you are going to develop a literature review of 20 to 25 pages. This is not including cover page, abstract, and references. Every page should be well developed, succinct, and follow the guidelines. Many authors like to begin with an “Introduction” section that identifies the general topic and its importance. This is followed by the “Literature Review” section that provides the overview of previous research and explains what has and what has not already been learned. Much of the focus of the literature review is on previous research related to the subject under study. This includes most recent research over the past 7 years, theories, evidence best practices, common findings among studies, critical areas that still need research. 4. The review should follow APA Guidelines 6th edition. Sections to be developed: Introduction:

- 9. The introduction to the LR sets the stage by describing the boundaries of the literature search (LS) within the field of study. The researcher’s LS gathers, analyzes, and synthesizes research articles, research reports, seminal books, governmental and institutional reports, historical documents, archival media, and so on, to discover and present the state of knowledge concerning the topic under study. Available time, critical skills, prior knowledge, and scholarly discernment allows the researcher to know how far and wide to search to support their research. The search must, in the end, meet the twin aims of establishing 1) comprehensive coverage of the literatures pertinent to the problem and 2) relevance in the selection and application of literatures. Since research problems exist within determinate and specified social contexts and since bodies of literatures attach to these problems, the research problems themselves offer contextual and literature boundaries for the LS. Machi and McEvoy (2012) suggest the introduction should contain “six sections . . . (1) the opening, (2) the study topic, (3) the context, (4) the significance, (5) the problem statement, and (6) the organization” (p. 145). These sections are designed to orient the reader to the problem-at-hand and provide an outline of how the LR argument will be pursued. A good academic introduction provides the reader with a clear description of what lies ahead of them and the specific reasoning steps the author will use to take the reader through to a logical end. Graduate students are advised to use Machi and McEvoy’s sections as sub-headings in their Literature Review— adapting and modifying the headings to meet the needs of their individual study and LR argument. (See Machi and McEvoy text for descriptions of the sub-sections listed here. Conceptual Framework: The use of a conceptual framework as an argumentative

- 10. structure for the LR is very important. Conceptual framework is a term for the epistemological position a researcher uses to approach a set of phenomena. The position is “conceptual” because whenever phenomena are experienced, they are associated with concepts the researcher possesses—that is, the researcher’s existing knowledge. Concepts “frame” how the researcher views phenomena, and thus necessarily shape how the researcher understands what is observed. Conceptual frameworks display objectivity and creativity by reflecting the researcher’s position as 1) a member of a scholarly community of knowledge; and 2) a scholar possessing a unique noetic outlook on the world, respectively. A researcher’s ideas must be objectively grounded in well-confirmed concepts employed by a community of practice, which validates and confirms knowledge through communal truth-seekingactivities. Yet a researcher also always possesses ideas which are unique, by virtue of her or his individual and distinct noetic perspectives on the world, which allow for creative new associations, applications and developments of concepts. The interplay between unique researcher perspectives and communal truth- seeking activities allows for the creation and confirmation of new knowledge through creative acts of individuals (and groups of individuals) that are then validated by the community. The two-fold insight here is that: 1) not all new ideas are objectively valid or rationally justifiable to the community of practice; and 2) existing concepts in the community of practice admit of addition, revision, and even overturning (see Kuhn, 1962; Feyerabend, 1975). a conceptual framework is an argument about why the topic one wishes to study matters and why the means proposed to study it are appropriate and rigorous. By argument, we mean that a conceptual framework is a series of sequenced, logical propositions the purpose of which is to convince the reader of the study’s importance and rigor. Arguments for why a study

- 11. “matters” vary greatly in scale, depending on the appropriate audience. In some scholarly work, the study may only matter to a small esoteric community, but that does not change the fact that its conceptual framework should argue for its relevance within that community. Finally by appropriate and rigorous, we mean that a conceptual framework should argue convincingly that (1) the research questions are an outgrowth of the argument for relevance [emphasis added]; (2) the data to be collected provide the researcher with the raw material needed to explore the research questions; and (3) the analytic approach allows the researcher to effectively respond to (if not always answer) those questions. Further, rigor includes not only how a study is carried out, but also how the methodology itself is conceptualized. As we will see in Chapter 4 and Chapter 5 in particular, methodology is neither objective nor value-neutral. As such, what you study and how you study it ultimately raises questions about who you are, what kinds of questions you ask, the assumptions embedded within those questions, and the extent to which those assumptions are made explicit and, where appropriate, subjected to critique. (Ravitch & Riggan, 2012, p. 7) Review of the Research Literature The review of research literature is the core of the literature review and provides the evidence-base that your literature needs. This review must be undertaken with scientific organization and must employ the researcher’s best analytic and descriptive skills in order to provide the reader with an accurate picture of the state of research in the field. Szuchman and Thomlison (2011) describe three different types of reviews of research literature: “empirical,” “theoretical,” and “systematic.” Empirical reviews are a synthesizing summary of prior research that “presents a state of knowledge in an area” (p. 62). Theoretical reviews provide critical analyses of the current theoretical perspectives in the literatures. And systematic

- 12. reviews are undertaken in quantitative studies to provide “a formal synthesis of experimental research studies designed to explain how particular interventions affect specific outcomes” (p. 62). The literature review will necessarily involve empirical and theoretical considerations. Summary of the Litrature Review A comprehensive overview of the literature review. Tips: VI. The literature review provides a comprehensive and relevant review of literature that pertains to a topic in the research. The primary purpose of the literature review is to identify the topic, problem, research hypothesis, within the framework of previous research on the topic. The review provides a reasoned argument to the claim that the research question guiding the study reveals an area of investigation that is a new avenue of research, or a research avenue that has not been adequately studied or sufficiently confirmed. The LR argument uses the analyzed and critiqued literatures as a base of evidence to justify the argument’s main claim. The presentation of this evidence base demonstrates to the reader that the researcher understands the field of study and the position the current study occupies within the community of scholarshipPrewriting involves the preparation and arrangement of your ideas before writing them into a paper. Use whatever techniques work for you (e.g.– Freewriting, Brainstorming, Listing, Outlining, Questioning, Clustering). Your research and documentation are accomplished during the prewriting stage. C. Sources 4. Generate material from outside sources. You must use at minimum 25 sources for your literature review. These sources

- 13. MUST be credible, quality academic sources. 5. Peer-reviewed sources are preferred (journals and books published at university presses). You can find such sources through Albizu University’s online library. The Library Research Portal there will help you find scholarly journals. 6. Because this research assignment has many possible facets you can explore, you may have a valid reason for using a non- peer reviewed sources. Exceptions include the following: a. Online databases of historical texts/documents (where the sponsoring organization, editorial board, and information about the original printed source are clearly identified) b. Professional organizations (usually ending in a .org suffix) c. Government agencies (ending in a .gov suffix) d. Websites with the “.edu” extension are not necessarily reliable ones as many different people have access to posting articles on such sites. Additionally, faculty material published on such sites have not been subject to the rigorous review process required by print publications (Just because someone has the degree doesn’t mean his/her entire body of work is recognized by the academic discipline in which he/she operates). D. Research a. Go through your sources and take notes on information relavent to your topic. b. Be creative & original in selecting information. Understand methodologies used, common themes, identify gaps in the research, the theoretical frameworks applied.

- 14. c. Once you’ve discovered your purpose for writing, that purpose will inform the rest of your note taking. d. Document! When you’re getting ideas from outside sources, you must take special pains to identify that material as such, so record all bibliographical information and make note of the page source of every quotation you retrieve. Doing this now, at the prewriting stage, will save you much grief later on. VII. Thesis Statement/Purpose Statement: For this assignment, you should prepare it beforehand; use it as a heading. VIII. Outline and write your literature review. The way you synthesize material is unique to you. Your arrangement of various points can be original. Your own interpretations and ideas can be incorporated. Look for gaps in your sources: there may be a point that is not stressed or an obvious conclusion that is overlooked. Remember to stay in line with your topic and that you will use this literature review to guide your proposal; especially the needs statement and background. IX. Revise, Edit, and Proofread A. Check your thesis statement. Does it clearly articulate all the points you’ve covered in your review? Are any points mentioned that aren’t covered in your review? B. Check your body paragraphs against your thesis (25 page review). Are they related to your thesis? Are they analytical? Do you discuss the research literature, the methodological literature, do you have a strong background and problem statement?

- 15. C. Check the details of your body paragraphs. Do you have enough support for your topic sentence? Are all the details in each body paragraph directly related to their respective topic sentence? Are the points you’re making arranged in such a way that your reader can clearly follow your line of thinking? Do you have too much outside support (so much so that it overwhelms your voice)? D. Read your paper carefully (out loud is suggested). E. Check your compliance with APA format. Review in-text documentation and works cited page (using APA Handbook to do so). Check for any missing citations; fix if necessary. F. Papers are to be reviewed by students support services before submitted and you must upload them to Bb and turnitin for a plagiarism check. X. Submit the final draft of your paper by the deadline stated. Examples of Proper Literature Reviews Example #1: A Brief Section of a Literature Review (Lin and Dembo 2008) The first example presented is from a research article (Lin and Dembo 2008:35) that sought to explain why some juveniles use illegal drugs and others do not. One of the theories being used by the authors is social control theory. The following section is part of the literature review that discusses previous research findings on the role of this theory in predicting juvenile drug use. Hirschi’s (1969) social control theory argued that adolescents who had no strong bond to conventional social institutions were

- 16. more likely to commit delinquency. Many empirical studies that follow Hirschi’s theory found general support that juveniles who have strong social bonds are engaged in fewer delinquent acts (Agnew 1985; Costello and Vowell 1999; Erickson, Crosboe, and Dornbush 2000; Hindelang 1973; Hirschi 1969; Junger-Tas 1992; Sampson and Laub 1993; Thornberry et al. 1991). Some studies that specially employed social control theory to explain juvenile drug use have also found support for this theory (Ellickson et al. 1999; Krohn et al. 1983; Marcos et al. 1986; Wiatrowski, Griswold, and Roberts 1981). By reviewing these studies, one can find that during the adolescent period (12-17), family and school play influential roles in influencing youngsters’ behavior. Whereas a defective family bond increases the probability of youthful drug use or juvenile delinquency (Denton and Kampfe 1994; Wells and Rankin 1991; Rankin and Kern 1994; Radosevich et al. 1980), students who have a weak school bond also have a higher risk of drug use (Ahlgren et al. 1982; Bauman 1984; Radosevich et al. 1980; Tec 1972). Notice especially the following: (1) the thorough overview of previous research, (2) the large number of previous research studies referenced, (3) the succinct and well-organized writing style, and (4) the manner in which previous studies are cited. Also note the following formatting guidelines: 1) If name of author(s) is in the text, put DATE OF PUBLICATION in parentheses. 2) If one author, use NAME and DATE OF PUBLICATION (and no punctuation between them). 3) If two authors, use NAME and NAME and DATE OF PUBLICATION.

- 17. 4) If three authors, use NAME, NAME, and NAME and DATE OF PUBLICATION. 5) If four or more authors, use NAME et al. and DATE OF PUBLICATION. 6) If two or more citations are listed together, order them alphabetically by first author’s last name. Example #2: A Brief Section of a Literature Review (Rogoeczi 2008) The second example is from a research article (Rogoeczi 2008) that examines whether living in crowded conditions has the same or a different effect on women and men. The following section is part of the literature review that discusses previous research findings on the effect of lack of space in a room on aggressive actions by women and men. Note that the section comments on the fact that not all previous research is consistent. This sometimes is the case and is important to note. Experimental research varying room size reveals a relatively consistent pattern of gender differences, with more aggressive responses to limited space found among males than those observed among women (Baum and Koman 1976; Epstein and Karlin 1975; Freedman et al. 1972; Mackintosh, Saegert, and West 1975; Stokols et al. 1973). Studies examining the effects of density on children also report sex differences in response to density, with boys displaying heightened aggression (Loo 1972, 1978). Research on gender differences in withdrawal has produced more mixed findings (e.g., Loo 1978). Still other research finds no evidence of sex differences in discomfort as a result of crowding (Aiello, Epstein, and Karlin 1975; Baum and Valins 1977) or in the impact of crowding (Evans et al. 2000). Several longitudinal studies of the impact of household crowding on psychological distress among college students

- 18. reveal no differential effect by gender (Evans and Lepore 1993; Lepore, Evans, and Schneider 1991). However Karlin, Epstein, and Aiello (1978) report more physical and psychological effects among crowded women than men. Once again, notice the following: (1) the thorough overview of previous research, (2) the large number of previous research studies referenced, (3) the succinct and well-organized writing style, and (4) the manner in which previous studies are cited. Example #3: An Extended Section of a Literature Review (Durkin, Wolfe, and Clark 2005). As an example of an extended section of a literature review, an article by Keith Durkin, Timothy Wolfe, and Gregory Clark (2005: 256-261) in Sociological Spectrum is used. The research examines the ability of social learning theory to explain binge drinking by college students. Tim Wolfe is chair of the Education department at Mount Saint Mary’s University and a Education graduate of Roanoke College. Introduction Research Purpose The abuse of alcohol by college students has been the focus of considerable concern for several decades. However, one specific pattern of alcohol consumption, known as binge drinking, has recently received a tremendous amount of attention from the media, college personnel, healthcare professionals and researchers in the behavioral sciences. Binge drinking involves the consumption of large quantities of alcohol in a single drinking episode. A number of researchers have operationally defined binge drinking as the consumption of five or more alcoholic drinks in a single setting (Alva 1998; Borsari and Carey 1999; Haines and Spear 1996; Hensley 2001; Ichiyama and Kruse 1998; Jones et al. 2001; Meilman, Leichliter, and

- 19. Presley 1999; Nezlek, Pilkington, and Bilbro 1994; Page, Scanlan, and Gilbert 1999; Shulenberg et al. 1996). Research has indicated that this behavior is a prevalent phenomenon on college campuses nationwide. For instance, a 1993 survey of 17,592 students from 140 colleges and universities, which was conducted by the Harvard School of Public Health, found that 44% of students reported they had engaged in binge drinking during the previous two weeks (Weschler et al. 1994). Subsequent studies conducted in 1997, 1999, and 2001 produced nearly identical results (Weschler et al. 2002). There is a growing consensus that binge drinking constitutes a very serious threat to the well being of many of today’s college students. In fact, binge drinking has been characterized as the foremost public health hazard facing college students (Weschler et al. 1995). Research has indicated that compared to other college students, binge drinkers are more likely to experience negative consequences as a result of consuming alcoholic beverages. These include blackouts, hangovers, missing class because of drinking, falling behind in their studies, doing something that they later regretted, arguing with friends, getting involved in physical fights, and getting into trouble with the police (Weschler et al. 1994; Weschler et al. 2000). The most recent research suggests that many of these aforementioned negative consequences are on the rise nationally (Weschler et al. 2002). Binge drinking is also related to engaging in high-risk sexual behaviors, thus putting these students in danger of contracting sexually transmitted diseases or having an unplanned pregnancy (Ichiyama and Kruse 1998; Meilman 1993; Smith and Brown 1998). Moreover, recent research has found that students who report getting drunk frequently have significantly higher odds of being victims of assault than their peers (Hensley 2001; Mustaine and Tewsbury 2000). Furthermore, it is estimated that more than half of the young adults who binge drink on a daily basis exhibit indicators of alcohol abuse or dependency (Shulenberg et al. 1996). Finally,

- 20. the tragic alcohol-related deaths of students at several colleges and universities highlight the potentially fatal consequences of this activity (Jones et al. 2001; Vicary and Karshin 2002). Research has further revealed that the negative consequences of binge drinking are not limited to the students who participate in this behavior. This activity also has an adverse impact on other members of the university community. The concepts of “secondary binge effects” (Weschler et al. 1994; Weschler et al. 1995) and “secondhand effects” (Weschler et al. 2002) have emerged in the literature to describe the problems that are the direct result of other students’ binge drinking. Some of these secondary binge effects include being verbally insulted or abused, being physically assaulted, having one’s property damaged, experiencing unwelcome sexual advances, and having sleep or studying disturbed because of the conduct of intoxicated students. The recent alcohol-related riots on a number of campuses and neighboring communities are also examples of these secondary consequences (Vicary and Karshin 2002). Neighbors living near campuses frequently report a lower quality of life as a result of student binge drinking because of noise disturbances, litter, drunkenness, vandalism, vomiting, and urination (Weschler 2002). Although a number of recent studies have sought to identify factors that are associated with binge drinking by college students (Alva 1998; Ichiyama and Kruse 1998; Page et al. 1999; Turrisi 1999; Weschler, et al. 1995), research that applies the various sociological perspectives, particularly theories of deviant behavior to this phenomenon is particularly limited. For instance, Durkin, Wolfe, and Clark (1999) applied social bond theory to the binge drinking behavior of undergraduate students at one private college. Also, Workman (2001) conducted an ethnographic study at one university to examine the social construction and communication of norms about excessive drinking among fraternity members. The relative absence of

- 21. sociological research on binge drinking is an extremely significant oversight. Given the fact that sociological theories of deviance typically have a strong explanatory value, the current undertaking can make an important contribution to understanding this problematic behavior. The purpose of the current undertaking is to apply one of the leading sociological explanations of deviant behavior, social learning theory (Akers 1985, 2000), to binge drinking by college students. Once again, notice the following: (1) the thorough overview of previous research, (2) the large number of previous research studies referenced, (3) the succinct and well-organized writing style, and (4) the manner in which previous studies are cited. In addition, notice how the authors use the last paragraph to explain the need for a sociological study of binge drinking. References Durkin, Keith F., Timothy W. Wolfe, and Gregory A. Clark. 2005. “College Students and Binge Drinking: An Evaluation of Social Learning Theory.” Sociological Spectrum 25(3): 255- 272. Lin, Wen-Hsu and Richard Dembo. 2008. “An Integrated Model of Juvenile Drug Use: A Cross-Demographic Groups Study.” Western Criminology Review 9(2): 33-51. Regoeczi, Wendy C. 2008. “Crowding in Context: An Examination of the Differential Responses of Men and Women to High-Density Living Environments.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 49(5): 254-268. Additional Helpful References Galvan, Jose L. 2009. Writing Literature Reviews: A Guide for Students of the Social and Behavioral Sciences. 4th ed.

- 22. Glendale, CA: Pyrczak Publishing. (This source provides a detailed step-by-step process of conducting and writing a literature review.) Machi, Lawrence A. and Brenda T. McEvoy. 2008. The Literature Review: Six Steps to Success. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. Page 3 of 12 Name: Statement of Focus (100 points) . 1. What area of ESE or Education do you feel YOU can change or improve? Please think of this in light of your proposed action research focus this term. I would like to focus on increasing on-task behavior during distance learning time in gifted students diagnosed with ADHD at elementary level. 2. Why is this change particularly meaningful to YOU as an educator? This change is particularly meaningful to me because, as an educator, I want my students to successfully engaged in academic learning time outside of the classroom setting. 3. What do other educators or professionals tell you when YOU discuss this topic with them?

- 23. Other educators agree that the classroom setting is the most successful one when it comes to knowledge acquisition because in this setting, students have less distractions than at home. Another concern that educators have in relation to this matter is that at home setting there is no scholar schedule and/or structure as in schools and also caregivers are not trained on teaching skills and most of the time responses to exercises/test can be biased by their help and/or other distractors environment related. 4. How is the desired outcome a part of YOUR educational philosophy? The School is the ideal setting for learning acquisition for gifted students, but they can also learn in home setting if they have the appropriate resources. Applying behavioral intervention programs to keep them focused and engaged on tasks can be a method to successfully increase their academic learning time. 5. Describe the situation with your student/group of students that you want to change by implicitly focusing on: (What is the problem you would like to improve) Who? What? When? Where? How? I would like to increase the on-task behavior during distance learning time for gifted students at elementary level, at home setting. I will apply a behavioral intervention plan, based on the results of a preference assessment previously done according to functions of the behaviors observed. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning

- 24. Volume 18, Number 2 April – 2017 Analysis of Time-on-Task, Behavior Experiences, and Performance in Two Online Courses with Different Authentic Learning Tasks Sanghoon Park University of South Florida Abstract This paper reports the findings of a comparative analysis of online learner behavioral interactions, time- on-task, attendance, and performance at different points throughout a semester (beginning, during, and end) based on two online courses: one course offering authentic discussion-based learning activities and the other course offering authentic design/development-based learning activities. Web log data were collected to determine the number of learner behavioral interactions with the Moodle learning management system (LMS), the number of behavioral interactions with peers, the time-on-task for weekly tasks, and the

- 25. recorded attendance. Student performance on weekly tasks was also collected from the course data. Behavioral interactions with the Moodle LMS included resource viewing activities and uploading/downloading file activities. Behavioral interactions with peers included discussion postings, discussion responses, and discussion viewing activities. A series of Mann-Whitney tests were conducted to compare the two types of behavioral interactions between the two courses. Additionally, each student's behavioral interactions were visually presented to show the pattern of their interactions. The results indicated that, at the beginning of the semester, students who were involved in authentic design/development-based learning activities showed a significantly higher number of behavioral interactions with the Moodle LMS than did students involved in authentic discussion-based learning activities. However, in the middle of the semester, students engaged in authentic discussion-based learning activities showed a significantly higher number of behavioral interactions with peers than did students involved in authentic design/development-based learning activities. Additionally, students who were given

- 26. authentic design/development-based learning activities received higher performance scores both during the semester and at the end of the semester and they showed overall higher performance scores than Analysis of Time-on-Task, Behavior Experiences, and Performance in Two Online Courses with Different Authentic Learning Tasks Park 214 students who were given authentic discussion-based learning activities. No differences were found between the two groups with respect to time-on-task or attendance. Keywords: authentic learning task, behavioral experience, online learning, Web log data, time-on-task Introduction The number of online courses has been growing rapidly across the nation in both K-12 and higher education. According to the U.S. Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), approximately half of all K-12 school districts nationwide (55%) had students enrolled in at least one online

- 27. course (National Center for Education Statistics [NCES], 2011). In higher education, more than 7.1 million students are taking at least one online course (Allen & Seaman, 2014). These numbers are projected to grow exponentially as more universities are striving to meet the increasing demand for online courses. Online courses are expected to provide formal learning opportunities at the higher education level using various learning management platforms (Moller, Foshay, & Huett, 2008; Shea & Bidjerano, 2014; Wallace, 2010). Consequently, E-learning systems, or learning management systems (LMSs), are being advanced to provide students with high quality learning experiences and high quality educational services in their online courses (Mahajan, Sodhi, & Mahajan, 2016). Although the quality of an online learning experience can be defined and interpreted differently by the various stakeholders involved, previous studies identified both time flexibility and authentic learning tasks as two key factors affecting successful online learning. Time flexibility has been regarded as the most appealing option for online learning (Romero & Barberà, 2011) as it allows online learners to determine the

- 28. duration, pace, and synchronicity of the learning activities (Arneberg et al., 2007; Collis, Vingerhoets, & Moonen, 1997; Van den Brande, 1994). Recently, Romero and Barberà (2011) divided time flexibility into two constructs, instructional time and learner time, and asserted the need for studies that consider the time attributes of learners, such as time-on-task quality. Authentic tasks form the other aspect of successful online learning. Based on the constructivist learning model, online students learn more effectively when they are engaged in learning tasks that are relevant and/or authentic to them (Herrington, Oliver, & Reeves, 2006). Such tasks help learners develop authentic learning experiences through activities that emulate real- life problems and take place in an authentic learning environment (Roblyer & Edwards, 2000). Authentic learning activities can take many different forms and have been shown to provide many benefits for online learners (Lebow & Wager, 1994). For example, authentic tasks offer the opportunity to examine the task from different perspectives using a variety of available online resources. Additionally, authentic tasks can be integrated across different subject areas to encourage diverse roles and engage expertise from various

- 29. interdisciplinary perspectives (Herrington et al., 2006). To maximize the benefits of authentic tasks, Herrington, Oliver, and Reeves (2006) suggested a design model that involves three elements of authentic learning: tasks, learners, and technologies. After exploring the respective roles of the learner, the task and the technology, they concluded that synergy among these elements is a strong contributor to the success of online learning. Therefore, online learning must be designed to incorporate authentic learning tasks that are facilitated by, and can be completed using, multiple types of technologies (Parker, Maor, & Herrington, 2013). Analysis of Time-on-Task, Behavior Experiences, and Performance in Two Online Courses with Different Authentic Learning Tasks Park 215 In summary, both time flexibility and authentic learning tasks are important aspects of a successful online learning experience. However, few studies have investigated how online students show different behavioral

- 30. interactions during time-on-tasks with different authentic learning tasks, although higher levels of online activity were found to be always associated with better final grades greater student satisfaction (Cho & Kim, 2013). Therefore, the purpose of this study was to compare behavioral interactions, time-on-task, attendance, and performance between two online courses employing different types of authentic tasks. Web Log Data Analysis Web log data analysis or Web usage analysis is one of the most commonly used methods to analyze online behaviors using electronic records of a system-user interactions (Taksa, Spink, & Jansen, 2009). Web logs are the collection of digital traces that provide valuable information about each individual learner’s actions in an online course (Mahajan et al., 2016). Many recent LMSs, such as CANVAS, or the newly upgraded LMSs, such as Blackboard or Moodle, offer various sets of Web log data in the form of learning analytics. The data usually contain course log history, number of views for each page, number of comments, punctuality of assignment submission, and other technology usage. Web log files also contain a list of user actions that occurred during a certain period of time (Grace,

- 31. Maheswari, & Nagamalai, 2011). This vast amount of data allows instructors and researchers to find valuable information about learners’ online course behaviors, such as how many times per day and how often students log in, how many times and how often they post to discussion boards, how many students submit assignments on time, how much time they spend on each learning task, etc. Web log data also provides personal information about online learners, such as each student’s profile and achievement scores, and each student’s behavioral interaction data, such as content viewing, discussion posting, assignment submission, writing, test taking, task performances, and communications with peers/instructor (Mostow et al., 2005). The data can be presented in the form of visualization to support students and instructors in the understanding of their learning/teaching experiences. Therefore, the Web log analysis method offers a promising approach to better understand the behavioral interactions of online learners at different points during the semester. Researchers can use Web log data to describe or make inferences about learning events without intruding the learning event or involving direct elicitation of data from online learners (Jansen,

- 32. Taksa, & Spink, 2009). Although Web log data is a source of valuable information to understand online behaviors, it also has to be noted that researchers must be careful when interpreting the data with a fair amount of caution because Web log data could be misleading. For example, an online student might appear to be online for a longer time than she/he actually participated in a learning activity. Therefore, prior to conducting the Web log analysis, a researcher needs to understand the type of behavioral data to be analyzed based on the research questions and articulates the situational and contextual factors of the log data. Using the timestamps showing when the Web log was recorded, the researcher can make the observation of behaviors at certain point of time and decide the validity of the online behavior (Jansen et al., 2009). Behavioral Interactions Previous studies have shown the benefits of analyzing Web log data to understand the online learning behaviors of students. Hellwege, Gleadow, and McNaught (1996) conducted a study of the behavioral patterns of online learners while studying a geology Web site and reported that learners show a pattern of

- 33. accessing the most recent lecture notes prior to accessing the Web site materials. Sheard, Albrecht, and Butbul (2005) analyzed Web log files and found that knowing when students access various resources helps Analysis of Time-on-Task, Behavior Experiences, and Performance in Two Online Courses with Different Authentic Learning Tasks Park 216 instructors understand the students’ preferred learning patterns. While analyzing log data to investigate learning effectiveness, Peled and Rashty (1999) found that the most popular online activities were, in general, passive activities, such as retrieving information, rather than contributing activities. Dringus and Ellis (2005) reported on how to analyze asynchronous discussion form usage data to evaluate the progress of a threaded discussion. Several recent studies showed a positive link between students' online activities and their final course grades. For example, Valsamidis and Democritus (2011) examined the relationship between student activity level and student grades in an e- learning environment and found that the quality

- 34. of learning content is closely related to student grades. Also, Dawson, McWilliam, and Tan (2008) found that when students spend more time in online activities and course discussions, they earned higher final grades. Similarly, Macfadyen and Dawson (2010) reported that the numbers of messages postings, email correspondences, and completed assessments were positively correlated with students' final course grades. Most recently, Wei, Peng, and Chou's study (2015) showed the positive correlations between the number of discussion postings, reading material viewings, and logins with students' final exam scores. Although the previous studies utilized Web log data to investigate the relationships between students' behavioral interactions and learning achievement, few studies examined how online students' behavioral interactions are different at different phases of online learning when involved in two types of authentic learning tasks. Online Learning Experience The overall online learning experience consists of continuous behavioral interactions that are generated while completing a series of learning tasks (Park, 2015). Therefore, an examination of the nature of the

- 35. learning tasks and the influences of the learning tasks on student behaviors is needed. The examined short- term learning experiences can then be combined to create a big picture of the online learning experience within a course. According to Veletsianos and Doering (2010), the experience of online learners must be studied throughout the semester due to the long-term nature of online learning programs. To analyze the pattern of behavioral interactions, this study employed time and tasks as two analysis frames because both time and tasks form essential dimensions of a behavioral experience, as shown in Figure 1. An online learning experience begins at the starting point (first day of the course) and ends at the ending point (last day of the course). In between those two points, a series of learning tasks are presented to provide learners with diverse learning experiences. As the course continues, the learner continues to interact with learning tasks and eventually accumulates learning experiences by completing the learning tasks (Park, 2016). Students learning experiences are built up from the previous learning tasks because learning tasks are not separated from each other as shown in the spiral area in Figure 1. Hence, to analyze behavioral interactions

- 36. in online learning, both the type of learning tasks and the time- on-task must be analyzed simultaneously. In this paper, the researcher gathered and utilized Web log data to visualize the behavioral interaction patterns of online learners during the course of a semester and to compare the behavioral interactions between two online courses requiring different types of learning tasks. Analysis of Time-on-Task, Behavior Experiences, and Performance in Two Online Courses with Different Authentic Learning Tasks Park 217 Figure 1. Online learning experience - time and tasks. Research Questions 1. Do online learners' behavioral interactions with Moodle LMS differ between a course employing authentic discussion-based learning tasks and a course employing authentic design/development- based learning tasks?

- 37. 2. Do online learners' behavioral interactions with peers differ between a course employing authentic discussion-based learning tasks and a course employing authentic design/development-based learning tasks? 3. Does online learners' time-on-task differ between a course employing authentic discussion-based learning tasks and a course employing authentic design/development-based learning tasks? 4. Does online learners' attendance differ between a course employing authentic discussion-based learning tasks and a course employing authentic design/development-based learning tasks? 5. Does online learners' academic performance differ between a course employing authentic discussion-based learning tasks and a course employing authentic design/development-based learning tasks? Method Setting In this study, the researcher purposefully selected two online courses as units of analysis. The two courses

- 38. were purposefully selected because of the different learning approach that each course employed to design authentic learning activities and the extent to which technology was used. Course A activities were designed based on the constructivist learning approach while Course B activities were designed based on the constructionist learning approach. Both the constructionist approach and constructivist approach hold the basic assumption that students build knowledge of their own and continuously reconstruct it through personal experiences with their surrounding external realities. However, the constructionist approach is Analysis of Time-on-Task, Behavior Experiences, and Performance in Two Online Courses with Different Authentic Learning Tasks Park 218 different from the constructivist approach in that constructionist learning begins with a view of learning as a construction of knowledge through constructing tangible projects or creating digital artifacts (Kafai, 2006; Papert, 1991). The title of Course A was Program Evaluation, in

- 39. which the major course activities consisted of textbook reading, weekly online discussions, and a final evaluation plan proposal. Students enrolled in this course were expected to read the textbook, participate in weekly discussion activities, and complete a program evaluation plan. Course B was titled Instructional Multimedia Design/Development, which consisted of a series of hands-on tasks to design and develop multimedia materials using different multimedia authoring programs. Students were required to review related literature and tutorials on multimedia design during the semester and to create audio- based, visual-based, and Web-based multimedia materials through a series of hands-on-activities. The comparison of course requirements, key learning activities, authentic tasks, and technology use between the two online courses is presented in Table 1. Table 1 Comparison of Course Requirements, Key Learning Activities, Authentic Tasks, and Technology use Between Courses

- 40. Course A Course B Course* requirements Textbook reading & online discussion Multimedia design/development Key learning activities nline discussion online discussion design/development design/development rsonal Website development module design/development world scenario and presented with

- 41. contextualized data for weekly discussions. -defined and open to multiple interpretations. each discussion topic. variety of related documents and Web resources. o create a course outcome (program evaluation plan proposal) that could be used in their own organization. create instructional multimedia materials to solve a performance problem that they identified in their own fields. scope of each multimedia project to solve the unique performance problems they had identified. different multimedia programs and apply various design principles that were related to their own projects.

- 42. Web based learning module that can be used as an intervention to solve the identified performance problem in their own organizations. Technology use Students utilized the following technology to share their ideas and insights via weekly discussions Students utilized the following technology to design and create instructional multimedia materials Analysis of Time-on-Task, Behavior Experiences, and Performance in Two Online Courses with Different Authentic Learning Tasks Park 219 based on the constructivist learning approach: -Word

- 43. -PowerPoint based on the constructionist learning approach: design tools Note. * A course in this study refers to a general online class that delivers a series of lessons and learning tasks (online lectures, readings, assignments, quizzes, design and development activities, etc.). ** Authentic tasks were designed based on 10 characteristics of authentic activities/tasks defined by Herrington et al. (2006). Both courses were delivered via Moodle LMS and met the Quality Matters (QM) standards. Moodle is an

- 44. open-source LMS that helps educators create online learning courses. It has been used as a popular alternative to proprietary commercial online learning solutions and is distributed free of charge under open source licensing (Romero, Ventura, & Garcia, 2008). QM specifies a standard set employed to certify the quality of an online course (www.qualitymatters.org). Both courses A and B in this study met the required standards for high quality online course design after a rigorous review process by two certified QM reviewers. Participants As two courses with different online learning tasks were purposefully selected, 22 graduate students who were enrolled in two 8 week long online courses participated in this study. Twelve students were enrolled in Course A, and 10 students were enrolled in Course B. Excluding four students, two who dropped from each course due to personal reasons, the data reported in this paper concern 18 participants, 10 students (4 male and 6 female) in Course A and 8 students (all female) in Course B, with a mean age of 32.60 years (SD = 5.76) and 35.25 years (SD = 9.66), respectively. The average

- 45. number of online courses the study participants had taken previously was 11.40 (SD = 4.88) for Course A and 11.38 (SD = 12.28) for Course B, indicating no significant difference between the two courses. However, it should be noted that the number of students who had not previously taken more than 10 online courses was higher in Course B (five participants) than in Course A (three participants). Fifteen of the 18 participants were teachers: five taught elementary school, five taught middle school, and five taught high school. Of the remaining three participants, one was an administrative assistant, one was a curriculum director, and one was an instructional designer. Analysis of Time-on-Task, Behavior Experiences, and Performance in Two Online Courses with Different Authentic Learning Tasks Park 220 Figure 2. Example of Web log data screen.

- 46. Data In this study, the researcher examined behavioral interactions by utilizing students’ Web log data acquired from Moodle LMS used in this study (Figure 2). The obtained sets of data were significant for this study because they contained timestamp-sequenced interaction activities that are automatically recorded for each student with pre-determined activity categories such as view discussion, post discussion, view resources, etc. Hence, it clearly showed the type of activities each student followed in order to complete a given online learning task. The researcher also ensured the accuracy of data by following the process to decide the validity of the online behavior (Jansen et al., 2009). First, the researcher clearly defined the type of behavioral data to be analyzed based on the research questions (Table 2), and second, the researcher articulated the situational and contextual factors of the log data by cross-examining the given online tasks and recorded students activities. Lastly, the researcher checked the timestamps for each activity to confirm Analysis of Time-on-Task, Behavior Experiences, and

- 47. Performance in Two Online Courses with Different Authentic Learning Tasks Park 221 the time and the length of data recorded. The data were then converted to Excel file format and computed based on three semester phases for further analysis. These phases were phase 1 ─ beginning of the semester, phase 2 ─ during the semester, and phase 3 ─ end of the semester. An example of a Web log data screen is presented in Figure 2. The data show online learner behaviors in chronological order. Based on the type of behavioral activities, the researcher identified two categories of behavioral interactions that affect task completion: interactions with the Moodle LMS and interactions with peers. Table 2 presents the two categories of behavior interactions and example behaviors for each category. Table 2 Categories of Behavioral Interactions and Description Categories of behavioral interaction Behavior description

- 48. (Operational definition) Interactions with Moodle LMS (# of times quiz participation - quiz completion and submission) (# of visits to the Resource page) (# of visits to files page - file uploading and file downloadng) Interactions with peers ion viewing (# of times discussion viewed) (# of times discussion posted - making initial posts) (# of times discussion responded - making comments or replies) Among the identified behaviors, quiz taking was excluded from the analysis because it was a behavioral interaction that only applied to Course A. Student attendance and time-on-task were collected from recorded attendance data and each student’s weekly reported time-on-task. Weekly performance scores

- 49. were also collected from the course instructors and from the students with student permission. Due to the different grading systems, task scores from the two courses were converted to a 1 (minimum) to 100 (maximum) scale and combined based on the corresponding weeks for each phase. Results Collected data were analyzed to answer each of the five research questions. Table 3 displays the descriptive statistics of behavioral interactions with the Moodle LMS, behavioral interactions with peers, time-on-task, attendance, and performance for each of the two courses. A series of Mann-Whitney tests (Field, 2013), the non- parametric equivalent of the independent samples t- test, were used to compare the two types of behavioral interactions, time-on-task, attendance, and performance between the two courses. The Mann-Whitney test was selected for use in this study because the data did not meet the requirements for a parametric test, and the Mann-Whitney test has the advantage of being used for small samples of subjects, (i.e., between five and 20 participants) (Nachar, 2008).

- 50. Analysis of Time-on-Task, Behavior Experiences, and Performance in Two Online Courses with Different Authentic Learning Tasks Park 222 RQ1: Do online learners' behavioral interactions with the Moodle LMS differ between a course employing authentic discussion-based learning tasks and a course employing authentic design/development-based learning tasks? The average number of behavioral interactions with the Moodle LMS between the two courses was compared using the Mann-Whitney test. Among the three phases compared, the average number of Moodle LMS interactions in phase 1 (weeks 2/3) was significantly different, as revealed in Figure 3. In phase 1, the average number of Moodle LMS interactions in Course B (M = 32.00, Mdn = 31.50) was significantly higher than the average number of Moodle LMS interactions in Course A (M = 19.60, Mdn = 20.00), U = 12.00, z = - 2.50, p < .05, r = -.59, thus revealing a large effect size (Field, 2013). In phases 2 and 3, however, the average number of Moodle LMS interactions were not significantly different between the two courses.

- 51. Nonetheless, the total number of Moodle LMS interactions between the two courses was significantly different as the total number of Moodle LMS interactions in Course B (M = 74.13, Mdn = 73.50) was significantly higher than the average number of Moodle LMS interactions in Course A (M = 59.70, Mdn = 65.50), U = 17.50, z = - 2.01, p < .05, r = -.47, indicating a medium to large effect size. Figure 3. Average number of behavioral interactions with the Moodle LMS for each phase of the semester for two courses. 0 5 10 15 20 25 30

- 52. 35 Phase1 Phase2 Phase3 Course A Course B Analysis of Time-on-Task, Behavior Experiences, and Performance in Two Online Courses with Different Authentic Learning Tasks Park 223 Table 3 Descriptive Statistics of Behavioral Interactions, Time, Attendance, and Performance Phase 1 (Weeks 2/3) Phase 2 (Weeks 4/5/6) Phase 3 (Weeks 7/8) All three phases Course A (n = 10) Course B (n = 8) Course A (n = 10)

- 53. Course B (n = 8) Course A (n = 10) Course B (n = 8) Course A (n = 10) Course B (n = 8) M SD M SD M SD M SD M SD M SD M SD M SD Behavioral interactions a LMS interactions 19.60(5.36) 32.00(9.37) 23.10(6.72) 19.63(7.15) 17.00(5.77) 22.50(12.09) 59.70(10.46) 74.13(19.28) Peer interactions 64.50(24.04) 86.75(42.60) 126.30(57.88) 58.25(25.39) 65.70(41.17) 48.25(22.38) 256.50(99.69) 193.25(69.77) Attendance b 9.90(2.99) 10.75(2.82) 15.20(3.05) 13.50(4.47)

- 54. 11.70(2.21) 9.75(4.20) 36.80(7.57) 34.00(9.15) Time-on-task c 375.00(53.59 ) 700.63(549.52 ) 564.00(155.27 ) 1919.38(1928.10 ) 252.50(140.34 ) 360.00(304.2 6) 1191.50(314.80 ) 2980.00(2713.6 5) Performance Task score d 185.43(11.02) 195.00(4.47) 241.25(29.71) 283.59(21.37) 79.00(15.23) 96.43(1.66) 505.68(46.31) 575.02(26.03) Note. a Average number of interactions per phase b Average number of course participations per phase (Logins) c Time presented in minutes d Scores ranging from 0 (minimum) to 200 (maximum) in phase 1, from 0 (minimum) to 300 (maximum) in phase 2, from 0

- 55. (minimum) to 100 (maximum) in phase 3 Analysis of Time-on-Task, Behavior Experiences, and Performance in Two Online Courses with Different Authentic Learning Tasks Park 224 RQ2: Do online learners' behavioral interactions with peers differ between a course employing authentic discussion-based learning tasks and a course employing authentic design/development-based learning tasks? The average number of behavioral interactions with peers for the two courses was compared using the Mann-Whitney test. Among the three phases, the average number of interactions with peers in phase 2 (weeks 4/5/6) was significantly different, as evidenced in Figure 4. In phase 2, the average number of peer interactions in Course A (M = 126.30, Mdn = 111.50) was significantly higher than the average number of peer interactions in Course B (M = 58.25, Mdn = 59.50), U = 7.00, z = - 2.93, p < .01, r = -.69, thus revealing a large effect size. However, the average number of peer

- 56. interactions was not significantly different between the two courses in phases 1 and 3, nor was the total number of peer interactions between the two courses significant. Figure 4. Average number of behavioral interactions with peers for each phase of the semester for the two courses. The findings for both research questions 1 and 2 show the statistical comparisons of Moodle LMS interactions and peer interactions between two online courses involving different types of authentic learning tasks. To help understand the exact type of behavioral interactions and possible patterns, the researcher visualized each student's behavioral interaction pattern, as shown in Figures 5, 6, and 7. Each category of students' behavioral interactions was imported into an Excel spreadsheet with different color themes (Figure 5). 0 20

- 57. 40 60 80 100 120 140 Phase1 Phase2 Phase3 Course A Course B Analysis of Time-on-Task, Behavior Experiences, and Performance in Two Online Courses with Different Authentic Learning Tasks Park 225 Figure 5. Legend of color themes. Student 1

- 58. Student 2 Student 3 Student 4 Student 5 Student 6 Student 7 Student 8 Student 9 Student 10 Figure 6. Behavioral interaction pattern for each individual student in Course A. Analysis of Time-on-Task, Behavior Experiences, and Performance in Two Online Courses with Different Authentic Learning Tasks Park 226

- 59. Student 1 Student 2 Student 3 Student 4 Student 5 Student 6 Student 7 Student 8 Figure 7. Behavioral interaction pattern for each individual student in Course B. Blue colors represent a student's course exploration activities, such as course viewing and other user viewing. Brown colors represent a student's interactions with the Moodle LMS, and green colors represent a student's interactions with peers. Each square in the pattern graph represents one occurrence of the case. Each pattern line represents the total behavioral interactions that occurred in each week. Through visual representations of behavioral interactions, different patterns were identified in the two courses. Most of the

- 60. students in course A showed a ( ) shape of behavioral patterns, while students in Course B showed a ( ) shape of behavioral patterns. In other words, students in Course A tend to show more behavior interactions as they move toward the end of the semester, while students in course B showed higher behavioral interactions in the first week of the semester and also at the end of the semester. RQ3: Does online learners' time-on-task differ between a course employing authentic discussion-based learning tasks and a course employing authentic design/development-based learning tasks? Time-on-task for weekly authentic tasks for the two courses was compared using the Mann-Whitney test. No significant differences were found in any of the three phases or for the entire semester (Figure 8). Analysis of Time-on-Task, Behavior Experiences, and Performance in Two Online Courses with Different Authentic Learning Tasks Park 227

- 61. Figure 8. Average time-on-task (in minutes) for each phase for the two courses. RQ4: Does online learners' attendance differ between a course employing authentic discussion-based learning tasks and a course employing authentic design/development-based learning tasks? Attendance for weekly authentic tasks for the two courses was compared using the Mann-Whitney test. No significant differences were found in any of the three phases or for the entire semester (Figure 9). Figure 9. Average attendance for each phase for the two courses. RQ5: Does online learners' academic performance differ between a course employing authentic discussion-based learning tasks and a course employing authentic design/development-based learning tasks? The average task score between the two courses was compared using the Mann-Whitney test. Among the three phases compared, the average scores in phases 2 and 3 were significantly different, as displayed in Figure 10. In phase 2, the average score in Course B (M = 283.59, Mdn = 290.00) was significantly higher

- 62. than the average score in Course A (M = 241.25, Mdn = 240.47), U = 9.00, z = -2.76, p < .01, r = -.65, revealing a large effect size. In phase 3, the average score in Course B (M = 96.43, Mdn = 96.43) was significantly higher than the average score in Course A (M = 79.00, Mdn = 85.00), U = 7.50, z = -2.94, p < .01, r = -.69, indicating a large effect size. However, the task scores were not significantly different in 0 500 1000 1500 2000 2500 Phase1 Phase2 Phase3 Course A Course B 0 2 4

- 63. 6 8 10 12 14 16 Phase1 Phase2 Phase3 Course A Course B Analysis of Time-on-Task, Behavior Experiences, and Performance in Two Online Courses with Different Authentic Learning Tasks Park 228 phase 1. The total task scores for the entire semester for the two courses were significantly different. The total score for Course B (M = 575.02, Mdn = 585.43) was significantly higher than the total score for Course A (M = 505.68, Mdn = 495.47), U = 8.00, z = -2.85, p < .01, r =

- 64. -.67, indicating a large effect size. Figure 10. Average score in each phase for the two courses. In addition to the Mann-Whitney test comparisons, a Spearman's rank-order correlation was also run to determine the relationship between all 18 students' behavioral interactions, time-on-task, and performance per week. Table 4 Significant Correlations between Behavioral Interactions, Time- on-Task, and Performance Weeks Correlation rs(16) p value * Week2 Discussion viewing - Discussion response .794 .000 Week3 Discussion viewing - Discussion response .639 .004 Week4 Discussion viewing - Discussion posting .742 .000 Resource viewing – Discussion posting .632 .005 Resource viewing – Discussion viewing .631 .005 Week5 Discussion viewing - Discussion posting .599 .009 Resource viewing – Discussion posting .792 .000 Resource viewing – Discussion viewing .703 .001 Week6 File uploading - Score .650 .003 File uploading - Discussion posting .732 .001 Week7/8 File uploading - Discussion posting .622 .006

- 65. Discussion viewing - discussion response .661 .003 Note. * All correlations are significant at the 0.01 level (2- tailed). Although no overall significant correlations were found between time-on-task and behavioral interactions, or between performance scores and behavioral interactions, there were several noticeable patterns found among behavioral interactions. For example, during the first half of the semester, strong positive correlations were found between discussion reviewing and discussion response /discussion posting 0 50 100 150 200 250 300 Phase1 Phase2 Phase3 Course A Course B

- 66. Analysis of Time-on-Task, Behavior Experiences, and Performance in Two Online Courses with Different Authentic Learning Tasks Park 229 behaviors. Then, during the second half of the semester, resource viewing, discussion posting, and file uploading behaviors showed strong positive correlations. Especially in week 6, students scored higher when they showed more file uploading behaviors with discussion postings. Discussion Time flexibility and authentic tasks are two factors that affect the success of an online learning experience. However, the type of behavioral interactions students exhibit at different points when they are involved in different types of authentic tasks is not well understood. Accordingly, this study attempted to analyze and visualize the behavioral interactions of online learners at different times during the semester and compare the occurrences of these behavioral interactions in two online

- 67. courses. The study found that online students exhibit different behavioral interactions when they are involved in two different authentic online learning activities. Students in authentic design/development-based learning activities demonstrated more behavioral interactions with the Moodle LMS at the beginning of the course, whereas students in authentic discussion-based learning activities exhibited more behavioral interactions with peers during the middle of the semester. Overall, attendance and time-on-task did not differ between the two courses. Understanding time flexibility as the capacity to spend time-on-task at different times of the day and week (Romero & Barberà, 2011), the results indicate that students are likely to be involved in behavioral interactions with the Moodle LMS early in the course if given tasks require authentic design/development learning activities. This finding could be viewed from the perspective of student time management. In other words, students in the design/development course tried to understand the scope of the design/development projects early in the semester so they could plan the design/development of the multimedia materials for the semester. This notion is supported by their attendance and time-on-task

- 68. (Figures 8 and 9). Although students in Course B did not actively participate in behavioral interactions with peers in the middle of the semester, they attended the course regularly and spent significantly more time working on given tasks compared with students in Course A. Given the different behavioral interaction patterns found in the different authentic online tasks, the findings support the importance of designing technological learning resources at different points of the semester depending on the type of authentic learning tasks and on the needs of the student (Swan & Shin, 2005). Another important finding of this study is that the correlations between student performance and each type of student behavioral interactions according to Spearman's rank correlation coefficients were not significant. The evidence offers the possibility of behavioral interactions being an intermediate variable, suggesting that more indicators must be examined to understand factors affecting student performance in online learning. In fact, many of the online learning analytics focus on behavioral indicators rather than on the psychological aspects of learning, such as cognitive involvement, academic emotions, and motivation.

- 69. Therefore, we must seek ways to incorporate a different methodology to approach the online learning experience in a holistic way. For example, the experience sampling method (ESM) combined with learning analytics would be a good alternative method to analyze the multiple dimensions of the online learning experience. Analysis of Time-on-Task, Behavior Experiences, and Performance in Two Online Courses with Different Authentic Learning Tasks Park 230 Conclusion This study analyzed the behavioral interactions of online learners and compared the differences in behavioral interactions for two online courses each with different authentic learning tasks. Since the first course was designed based on a constructivist approach, and the second course from a constructionist perspective, the analysis results showed that students in each

- 70. course experienced different behavioral interactions during the semester. The findings imply that when designing an online course that involves authentic learning tasks, instructional designers need to consider optimizing learners' behavioral interaction sequence to maximize their learning effectiveness. For example, interactions with peers should be encouraged when designing an online course based on the constructive belief (Lowes, Lin, & Kinghorn, 2015). Unlike other previous studies, however, this study did not find the direct relationship between the behavioral interactions, whether with Moodle LMS or peers, and performance scores. Previous studies such as Davies and Graff's (2005) also reported no relationship between discussion forum participation and final course grades. As discussed, behavioral interactions could be an intermediate variable affected by students' cognitive involvement and motivation, thus their psychological online learning experiences also need to be considered when analyzing students' Web log data. There are several limitations to this study. First, the behavioral interaction data collected using Web logs are limited only to internal data stored in the Moodle LMS server. External communication data, such as email

- 71. correspondences or conference calls, were not included in the data analysis. Second, although the study was conducted using two purposefully selected courses to provide a rich description of the behavioral pattern for each individual student, future researchers wanting to make generalizations about the findings of this study will need to increase the number of participants. Third, this study only analyzed the behavioral patterns of online learners, and thus, there is a need to examine how these behavior patterns are related to other learning experiences such as a cognitive processing and affective states. This holistic approach to understanding learning experiences will help researchers obtain a more comprehensive picture of the interactions among the cognitive processes, affective states, and behavioral patterns. With the meticulous analysis of the individual learner’s learning experience, we can gain deeper insight into ways to design the optimal online learning experience. References Allen, I. E., & Seaman, J. (2014). Grade change: Tracking online education in the United States. Babson Park, MA: Babson Survey Research Group and Quahog

- 72. Research Group. Retrieved from http://www.onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/gradechange.pdf Arneberg P., Keegan D., Guardia, L., Keegan, D., Lõssenko, J., Fernández Michels, P., & Zarka, D. (2007). Analyses of European mega providers of e-learning. Bekkestua: NKIforlaget. Cho, M. H., & Kim, B. J. (2013). Studentsʼ self-regulation for interaction with others in online learning environments. The Internet and Higher Education, 17, 69–75. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2012.11.001 http://www.onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/gradechange.pdf Analysis of Time-on-Task, Behavior Experiences, and Performance in Two Online Courses with Different Authentic Learning Tasks Park 231 Collis, B., Vingerhoets, J., & Moonen, J. (1997). Flexibility as a key construct in European training: Experiences from the Tele Scopia project. British Journal of Educational Technology, 28(3),