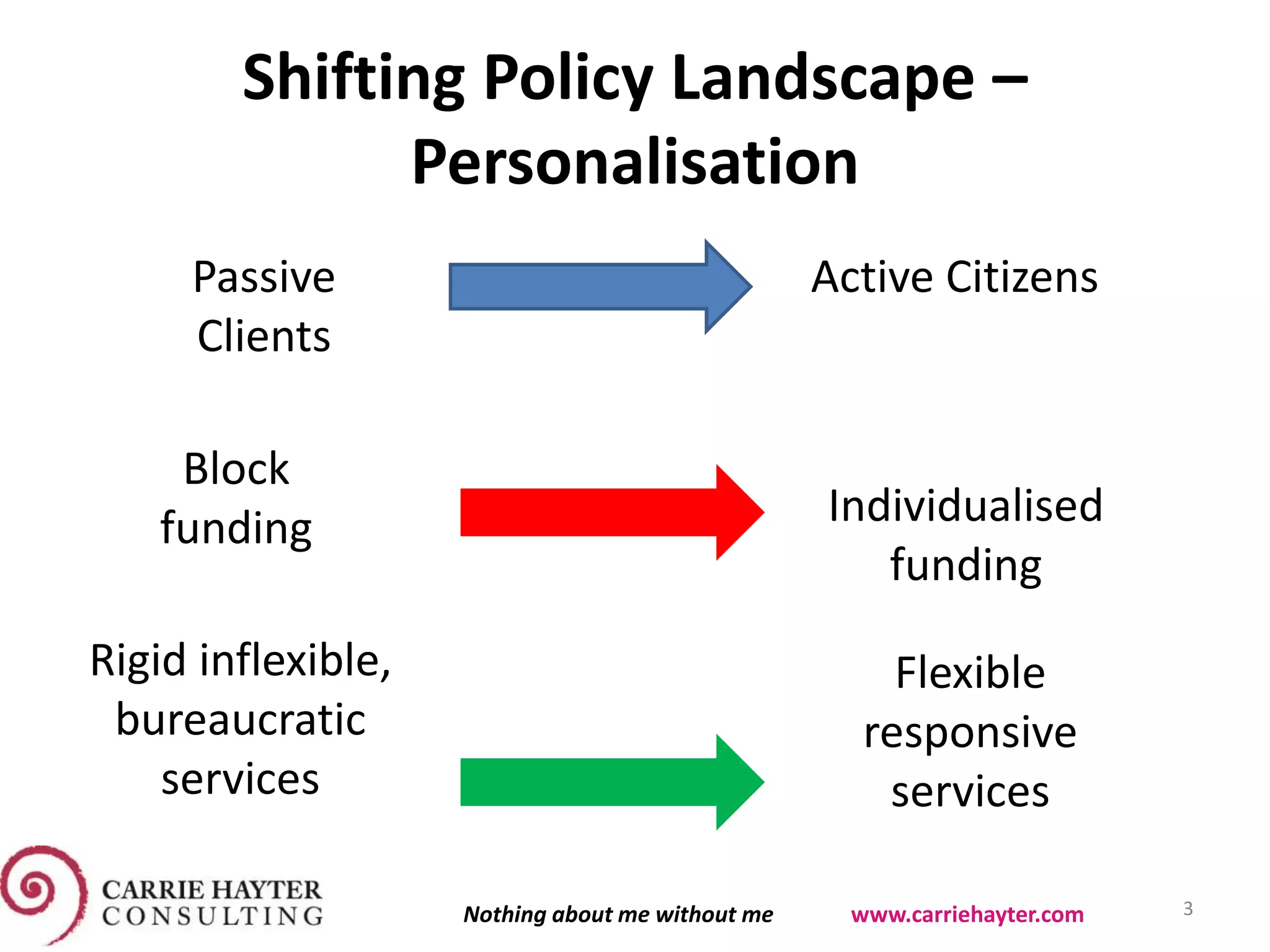

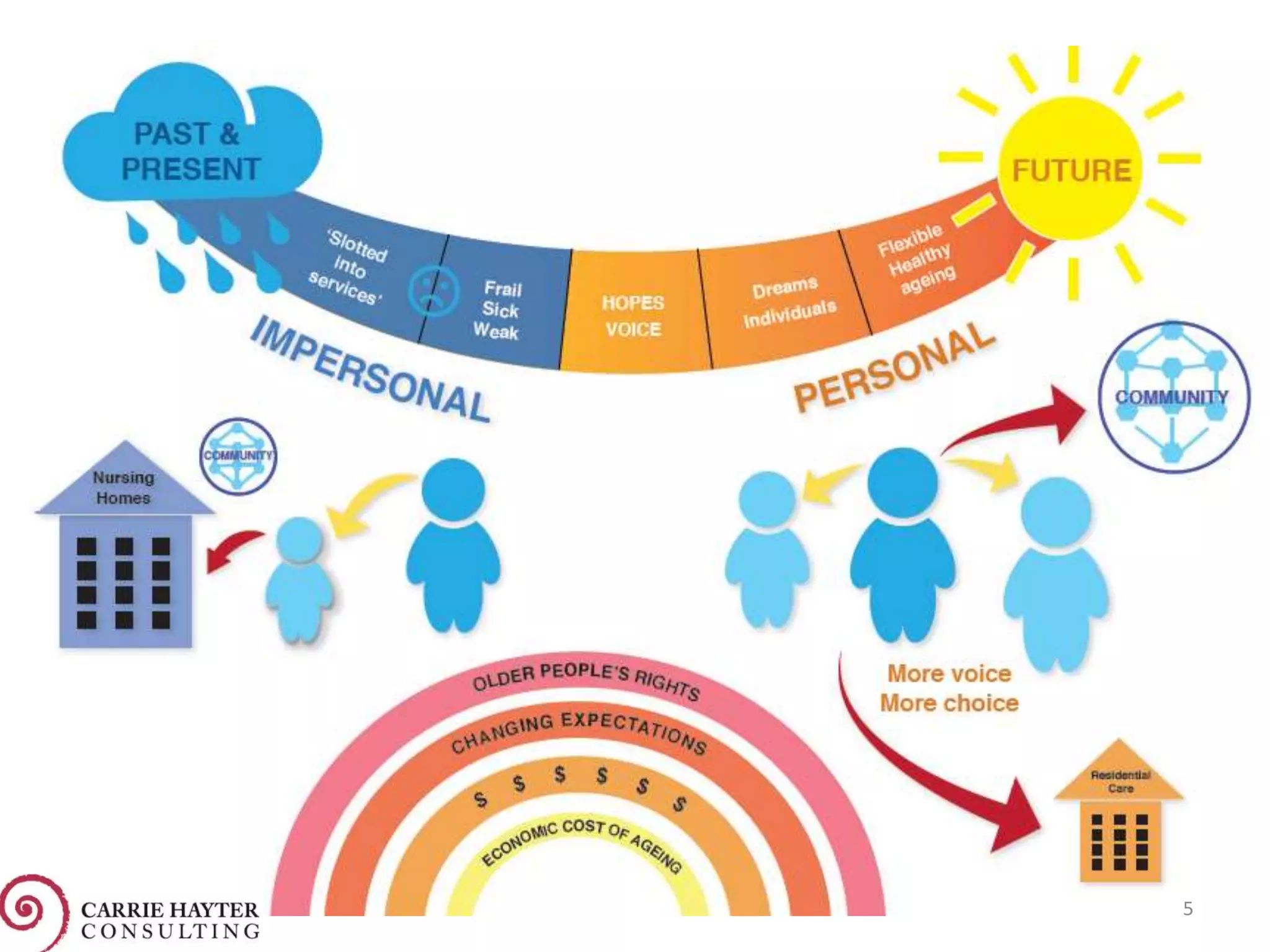

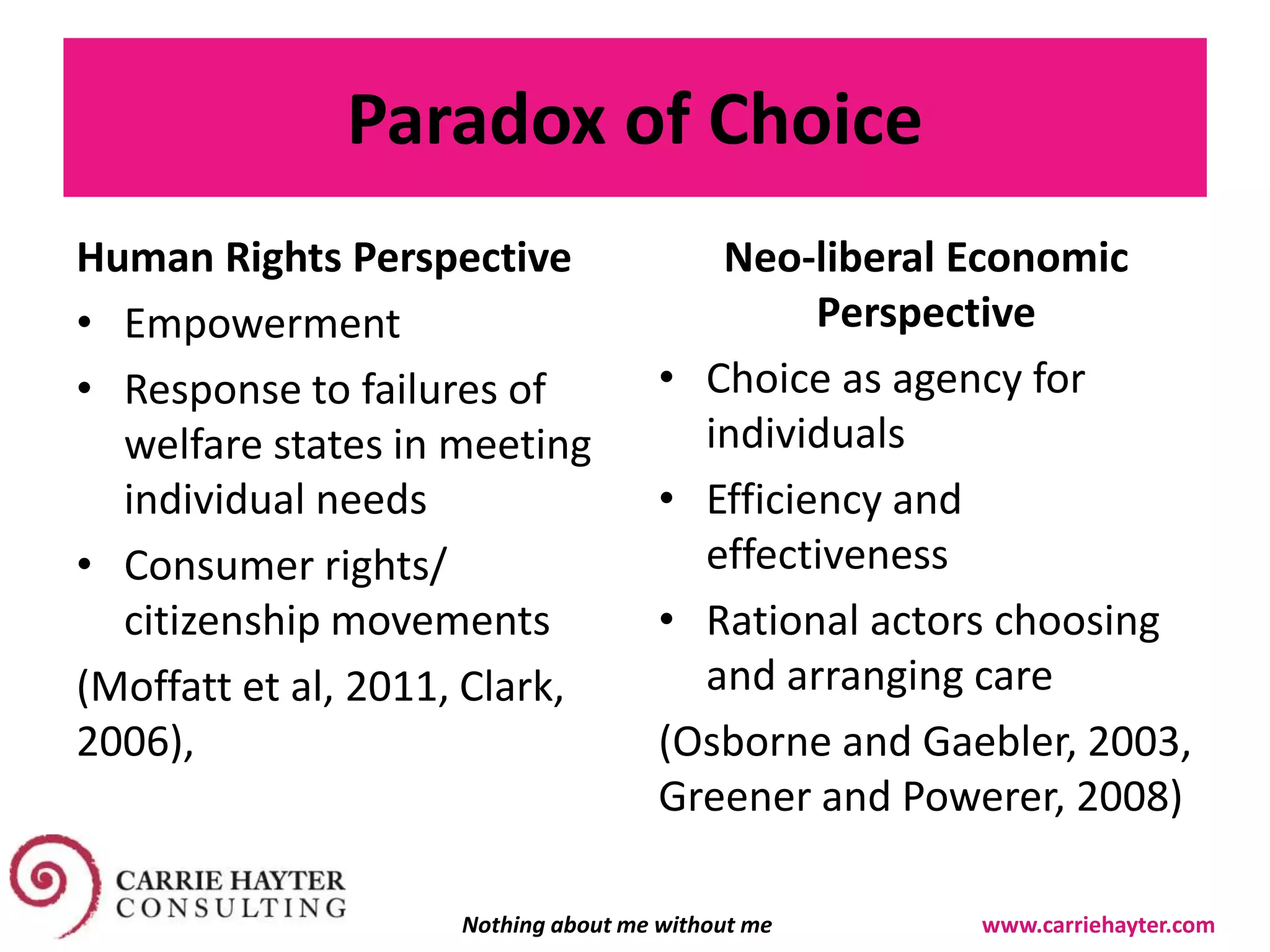

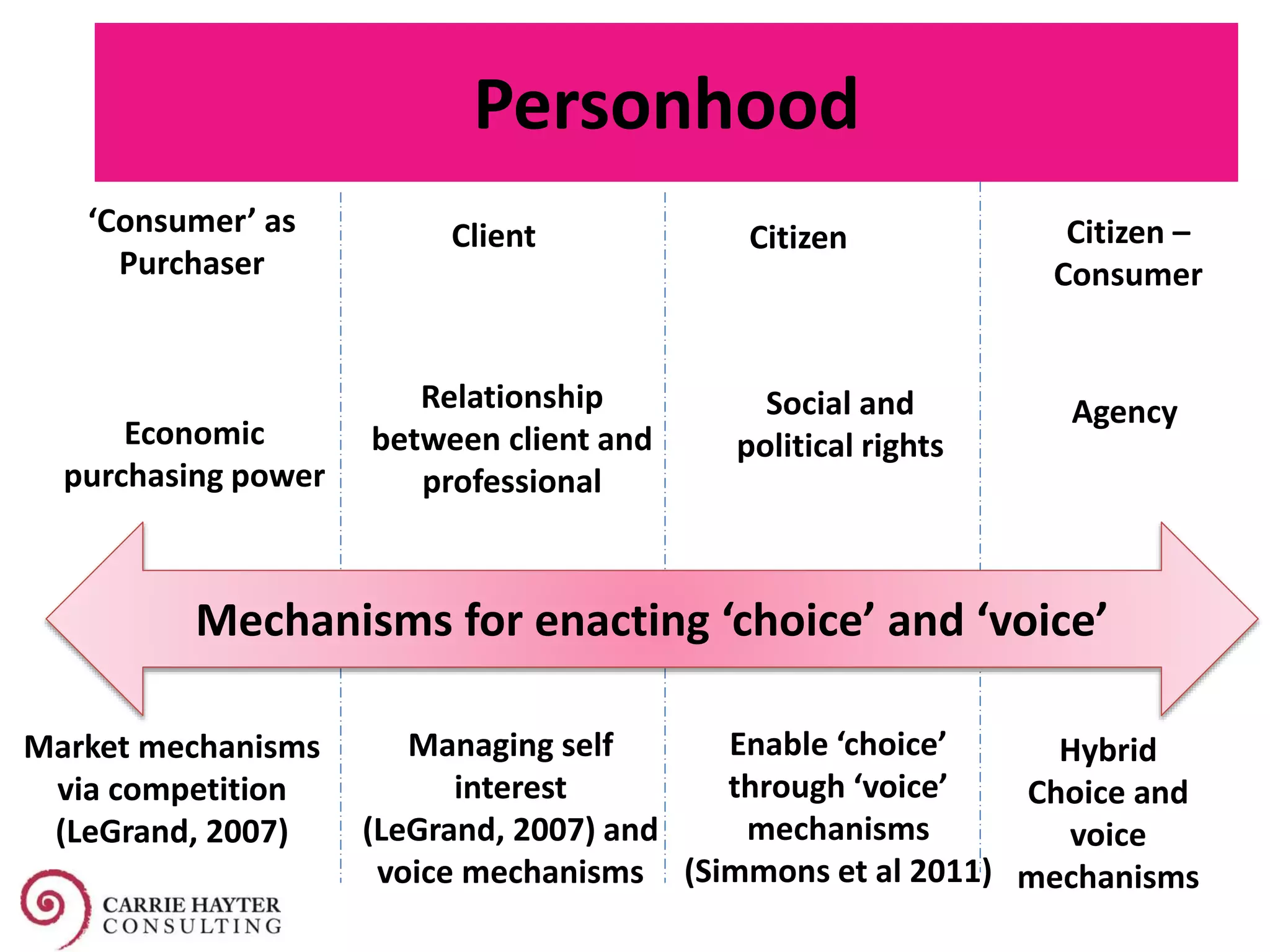

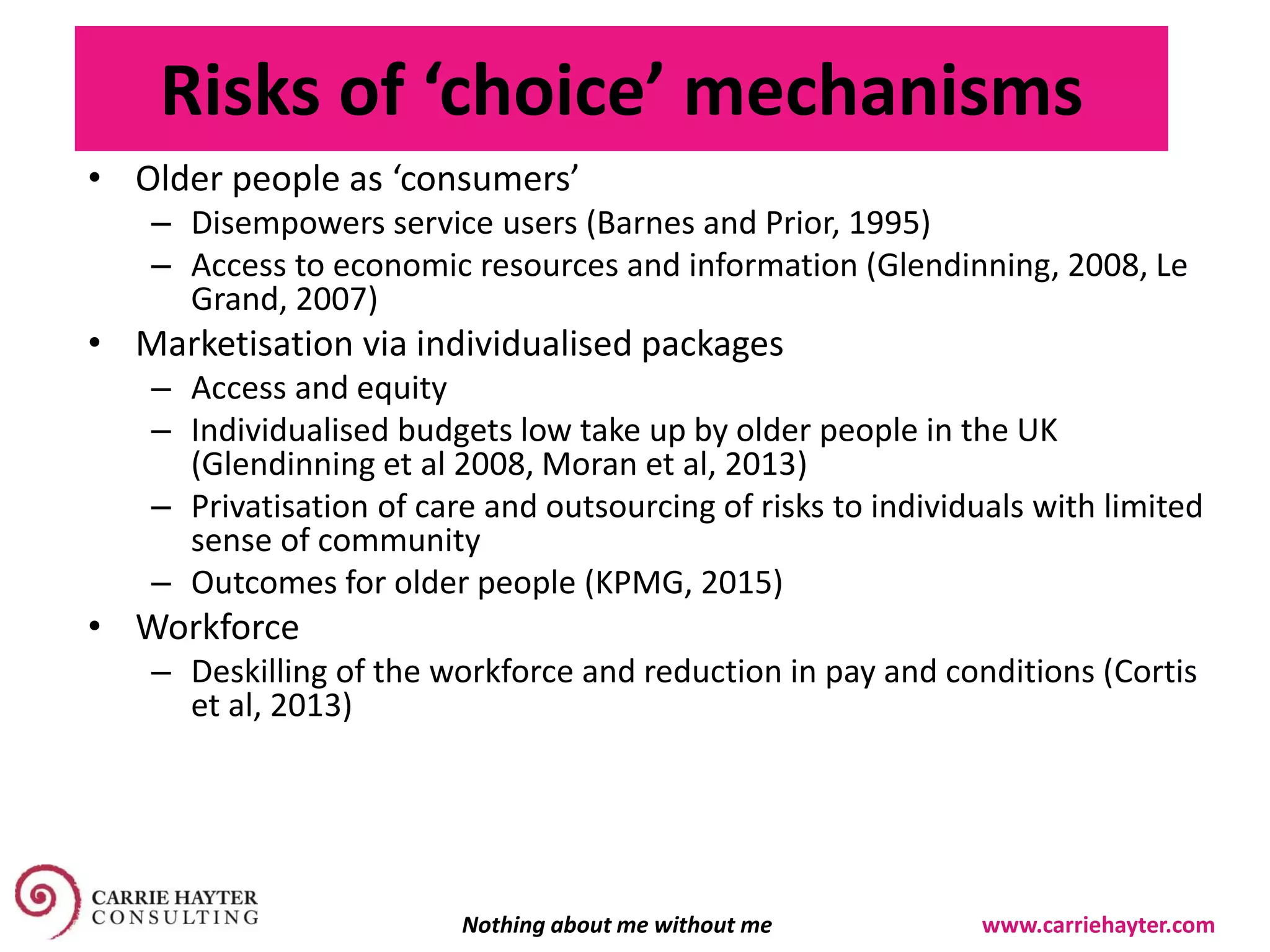

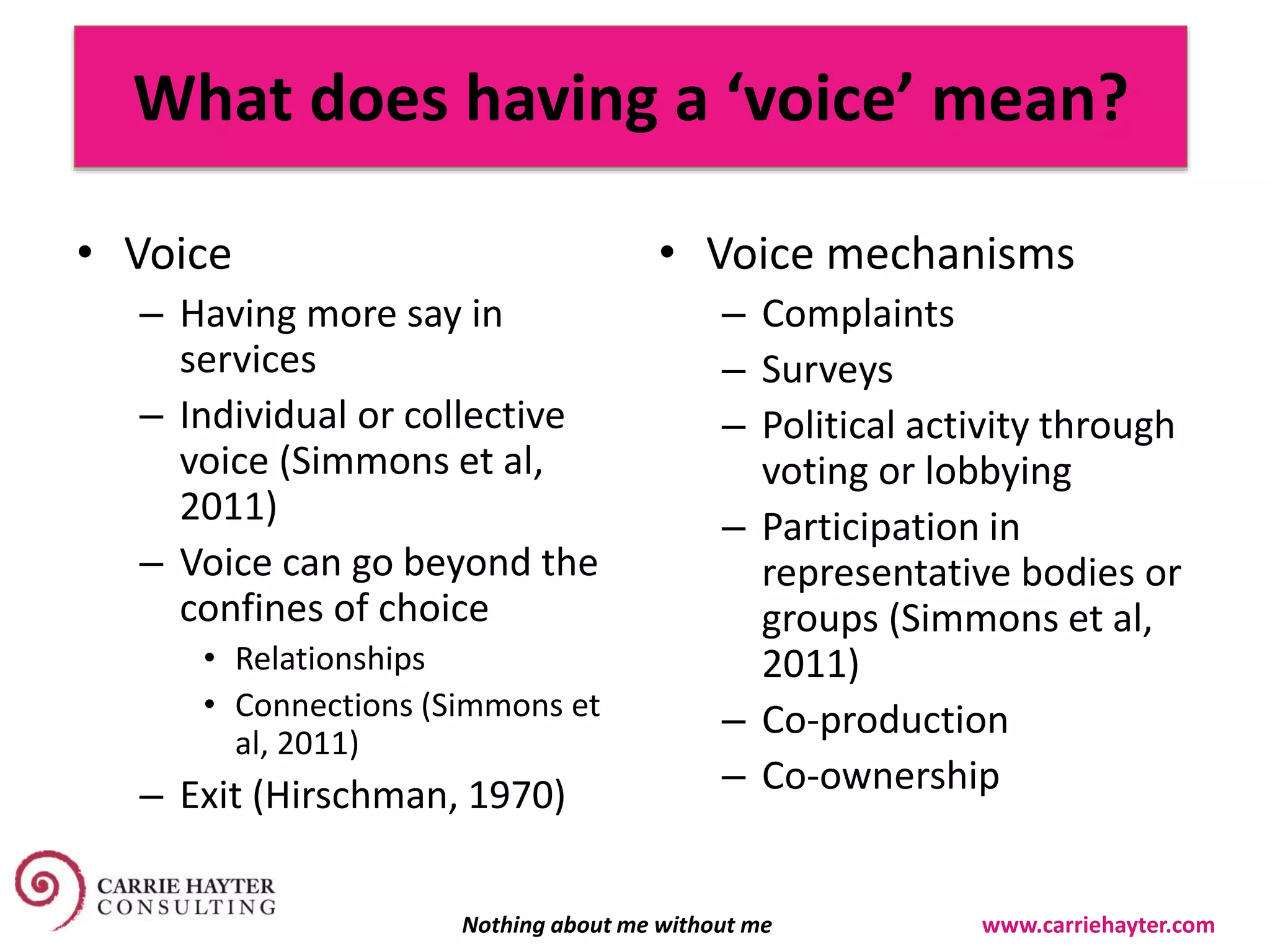

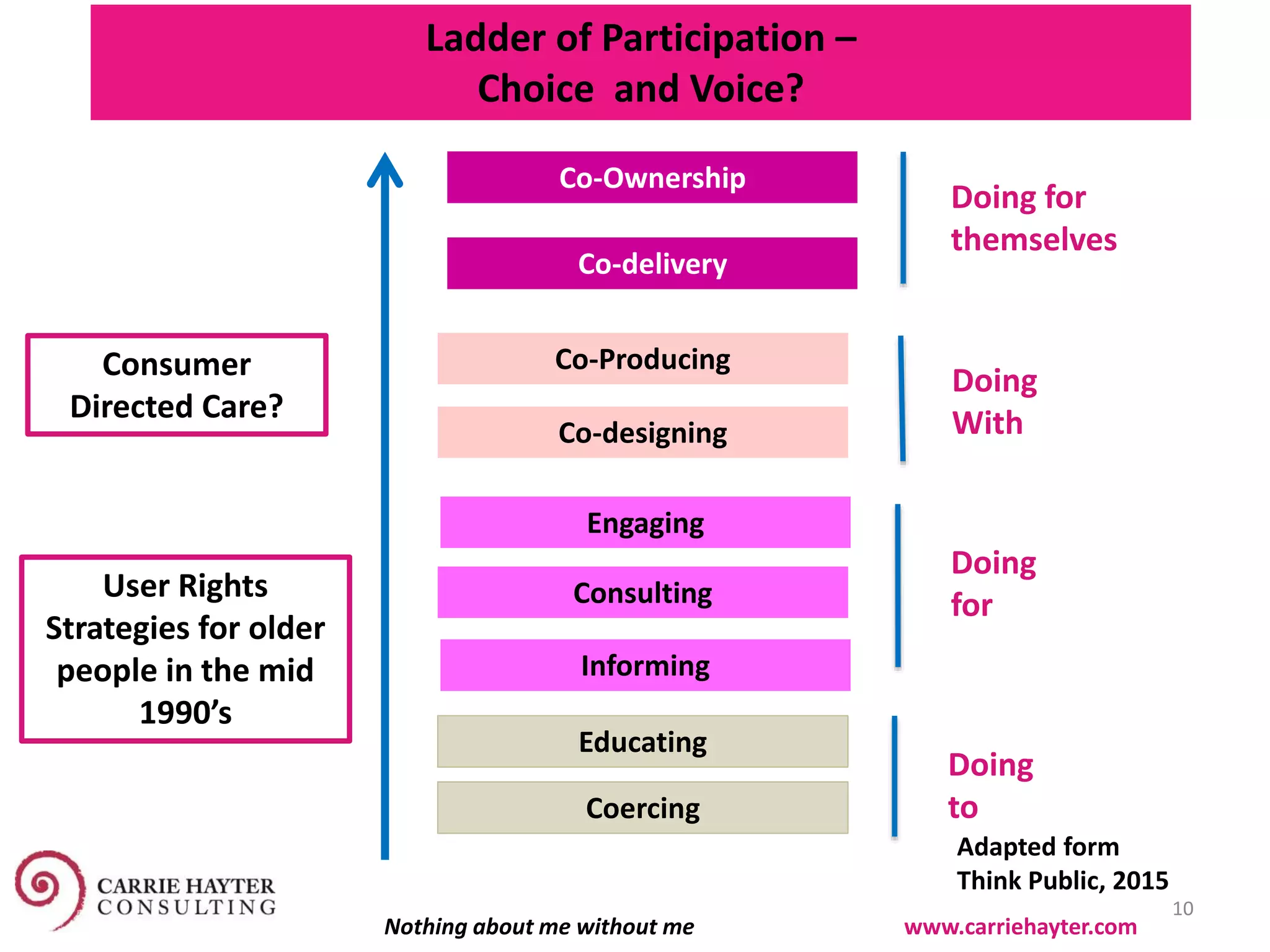

The document critically analyzes the concepts of choice and voice in consumer-directed care for older people in Australia, exploring the benefits and risks associated with these policy mechanisms. It highlights the importance of empowering older individuals and emphasizes the need for genuine engagement and representation in the care process. The conclusion suggests that understanding the paradox of choice and promoting guided advocacy can improve care outcomes for older citizens.