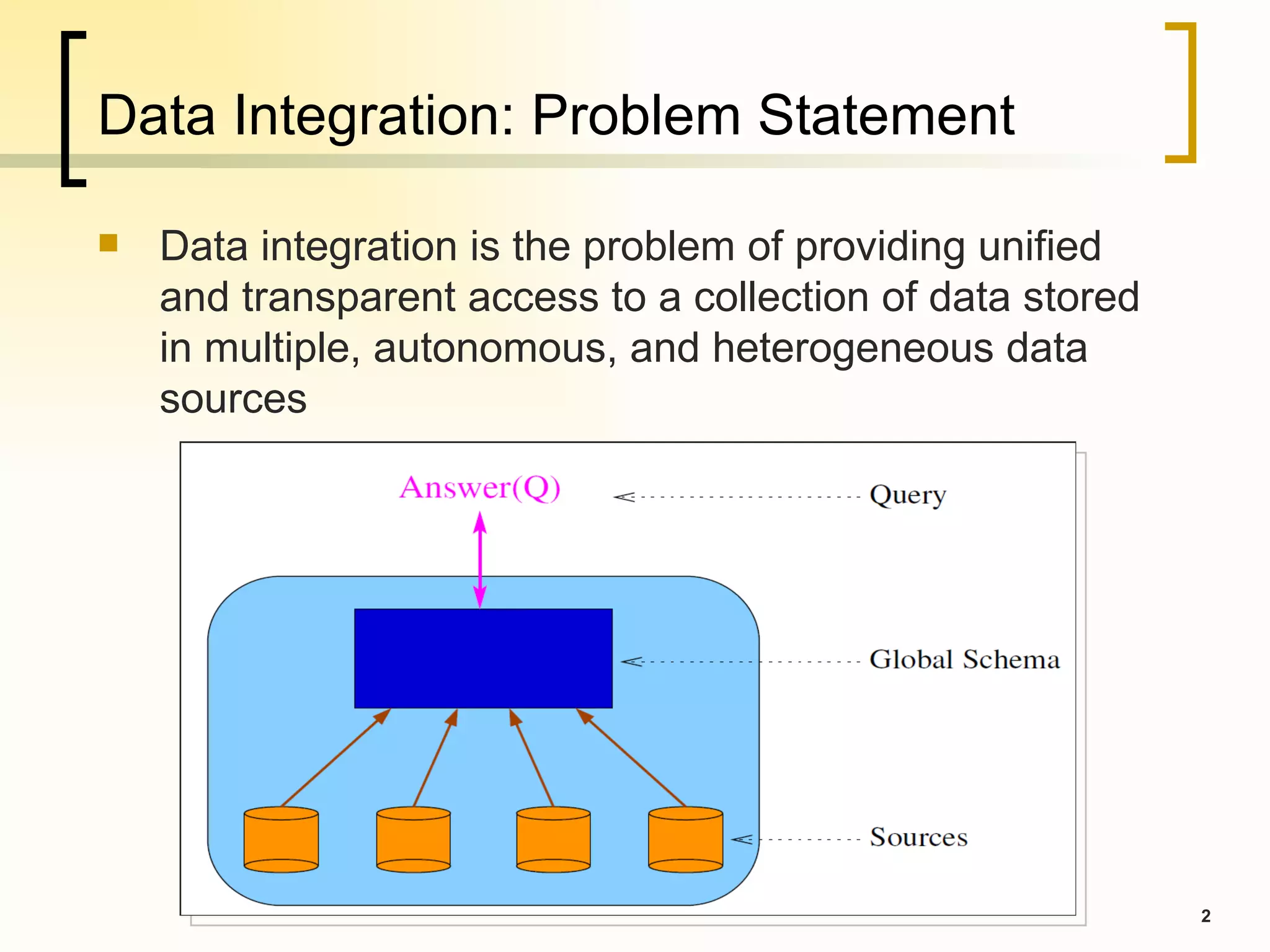

Data integration involves providing unified access to data stored across multiple heterogeneous data sources. There are several data integration architectures including data warehouses, virtual mediators, and peer-to-peer integration. Key challenges in data integration include modeling the global schema, source schemas, and mappings between them, as well as reformulating queries over the global schema to retrieve answers from the source schemas. Languages for modeling schema mappings include GAV, LAV, and GLAV, with different advantages for query reformulation and modularity when new sources are added.