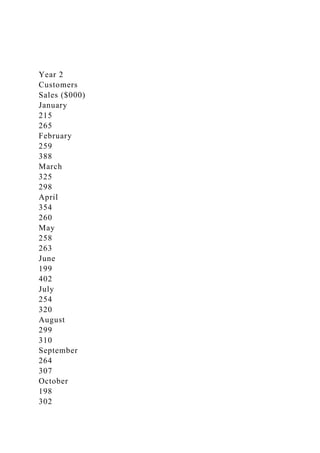

Year 2CustomersSales ($000)January215265February25.docx

- 2. November 223 225 December 261 361 Refugee Youth: A Review of Mental Health Counselling Issues and Practices E. Anne Marshall, Kathryn Butler, Tricia Roche, Jessica Cumming, and Joelle T. Taknint University of Victoria A global migration crisis has resulted in unprecedented numbers of refugees coming to Canada and other countries. A third of these refugees are youth, arriving with family members or alone. Although specific circumstances differ widely, refugee youth need support with language learning, education, and adjusting to a new country; a significant number also need mental health services. For this review paper, we focused on mental health issues and challenges refugee youth face, as well as counselling practices that have been found to be effective with these youth. There has been very little research specifically focused on refugee-youth mental health in Canada; however, the studies cited come from Canada, the United States, Australia, and European countries that have much similarity in their approaches to mental health counselling and psychotherapy. An overview of the refugee- youth context is presented first, followed by

- 3. a description of refugee mental health issues and challenges, a discussion of barriers to engagement with mental health services, and suggestions for effective mental health counselling practices for this population. The paper concludes with a summary of key findings from the literature and suggestions for future research to address the gaps in knowledge. Given the adversities many young refugees experience premigration, during migration, and after resettlement, it is not surprising that they experience mental health problems. Despite difficulties, young refugees demonstrate adaptability, perseverance, and resil- ience; having mental health professionals acknowledge their strengths and abilities will help them on their healing path and support them to adapt positively to a new home. Keywords: refugee youth mental health, review of refugee youth mental health, refugee youth mental health issues, counselling for refugee youth, mental health practices with refugee youth “Being a young refugee involves growing up in contexts of violence and uncertainty, experiencing the trauma of loss, and attempting to create a future in an uncertain world.” (Correa-Velez, Gifford, & Barnett, 2010, p. 1399). The world is experiencing a global refugee crisis. According to the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), there are close to 14 million refugees worldwide; the level of human displacement has increased by 50% since 2011 (United Nations High Commission for Refugees [UNHCR], 2016b). The Syrian refugee situation has received a great deal of attention

- 4. recently; the Government of Canada (2016) has reported that a total of 26,921 refugees have arrived in Canada from Syria since November 2015. Syria is one of the top 10 countries from which refugees have fled to Canada, the other nine being China, Hungary, Pakistan, Nigeria, Colombia, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, and Afghani- stan (Citizenship & Immigration Canada, 2016b). Together these countries accounted for almost half of the total refugee claims in Canada in 2015. Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC) has reported that just over 32,000 refugees became permanent resi- dents of Canada in 2015 (CIC, 2016a), contributing to a total of 149,163 refugees of all statuses living in Canada; 51% of these refugees are children and youth under the age of 25 (UNHCR, 2016a). In this paper youth typically includes ages 15 to 24 years because this age range is used for this population in most of the literature and institutional reports. Young refugees are a particularly vulnerable group. Although many figures pertaining to refugees in general are approximate because of their chaotic conditions, the reported numbers of refu- gee children and youth, in particular, are incomplete (Evans, Lo Forte, & McAslan Fraser, 2013). Evans et al. (2013) referred to refugee youth as an “invisible” population (p. 15). They noted that a third of the global population of displaced people is thought to be between the ages of 10 and 24, with almost half (47%) being under 18. In Canada in 2012, youth between the ages of 15 and 24 comprised 21% of the population of refugees admitted (Guruge

- 5. & Butt, 2015). A disturbing number of these refugee youth are orphans or travelling alone, either by choice or after separation from parents or caregivers; they are extremely vulnerable to ex- ploitation (UNHCR, 2016a). Newcomers who have been forced to flee their home countries experience a number of difficulties and barriers after arriving in their new host country. About 80% of refugee families receive some social assistance in their first year living in Canada, dropping to 50 – 60% in the second year (Statistics Canada, 2015b). In 2013, about half (52%) the government-assisted refugee youth (GARs) under 24 were employed; privately sponsored refugees fared bet- E. Anne Marshall, Educational Psychology and Leadership Studies and Centre for Youth & Society, University of Victoria; Kathryn Butler and Tricia Roche, Centre for Youth & Society, University of Victoria; Jessica Cumming, Educational Psychology & Leadership Studies, Uni- versity of Victoria; Joelle T. Taknint, Department of Psychology, University of Victoria. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to E. Anne Marshall, Educational Psychology and Leadership Studies, University of Victoria, PO Box 1700, Victoria, BC, Canada, V8W 2Y2. E- mail: [email protected]

- 6. Canadian Psychology / Psychologie canadienne © 2016 Canadian Psychological Association 2016, Vol. 57, No. 4, 308 –319 0708-5591/16/$12.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/cap0000068 308 mailto:[email protected] http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/cap0000068 ter, with an employment rate of 69% (Statistics Canada, 2015a). Even with the support available from all levels of government and private sponsors, many refugee youth and their families experience challenges in language learning, housing, employment, education, social relationships, and health, including mental health. For this review paper, we focused on mental health issues and challenges that refugee youth face and on good practices that have been found to be effective with these youth. Working with young refugees presents a distinct set of circumstances for counselling psychologists and mental health therapists. Given the adversities that these young people experience premigration, during migra- tion, and after resettlement, it is not surprising that they exhibit symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other men- tal health disorders (Fazel, Wheeler, & Danesh, 2005). Yet, despite these circumstances, young refugees also demonstrate adaptability,

- 7. perseverance, and resilience; they possess strengths and attributes that can help them adjust positively to a new home (Correa- Velez et al., 2010; Mawani, 2014). It is vital that mental health practi- tioners acknowledge and build upon the assets and potential these refugee youth possess. McKenzie, Tuck, and Agic (2014) observed that the Govern- ment of Canada Mental Health Commission’s strategy of 2012 acknowledged the need for improving services for refugees, but did not provide specific recommendations for designing and im- plementing such services. In their recent scoping review, Guruge and Butt (2015) pointed out that there has been very little research spe- cifically focused on refugee-youth mental health in Canada; the stud- ies cited in this paper come from Canada, the United States, Australia, and European countries that have much similarity in their approaches to mental health counselling and psychotherapy. The paper begins with a brief overview of key considerations related to refugee youth in general. Next, research and scholarly literature is presented, de- scribing the mental health challenges refugee youth may experience as well as factors that have been found to increase their levels of risk. Barriers to engagement in mental health services are then discussed, along with strategies to address those barriers. The fourth

- 8. section outlines several concepts and practices for effective mental health counselling with refugee youth. The paper concludes with a summary of key points related to youth-refugee mental health and suggestions for future directions. Key Considerations Related to Refugee Youth Because of the different situations affecting individual refugees and families, there are very few general principles that can be applied. One principle is priority or primacy of needs—similar to the hierarchy of needs concept articulated by Abraham Maslow (1943). Though refugee youth may have experienced severe psy- chological trauma before or during migration, safety and survival needs, such as shelter, food, and basic physical health must be addressed first. Beyond basic safety and survival needs, other key areas for supporting refugees include language, economic and family situation, education, and gender, discussed briefly below. Language Language is a key factor in resettlement because it affects all aspects of life in a new country. Refugees who have some knowl- edge of the host-country language are at a distinct advantage (Woods, 2009). Refugees are generally highly motivated to learn the language of their new location (Iversen, Sveaass, & Morken,

- 9. 2014); however, their schooling histories, experiences of trauma, and migration difficulties can present challenges to this acquisition (McBrien, 2005; Woods, 2009). In a short period of time, refugees have to catch up to peers in a new school (or study language at night if they are working), acquire functional and digital literacy, and learn to navigate a new culture, including its institutions, history, expectations, and norms. Because children and youth learn new languages more quickly than their parents, they are often called on to act as interpreters, or language brokers (Umaña- Taylor, 2003). This can result in young people having the respon- sibility to translate in situations that may be inappropriate for their developmental level or familial role. There is a high need for trained translators; resettlement assistance programs designed to meet other needs are increasingly being called upon to provide translation services, as these are not available elsewhere in the community (Citizenship & Immigration Canada, 2011). Refugee students have particular language-learning needs that require specialized curriculum and effective ways of integrating second-language learning and content learning (McBrien, 2005). Bilingual strategies that build on and validate students’ existing knowledge are effective but costly. Woods (2009) called for re- search on ways to incorporate language-learning technology in the classroom and to develop tools for use outside the classroom (e.g., through TV and Internet), particularly for refugee youth who are no longer in school. Providing accurate information in the

- 10. school curriculum and encouraging constructive and open-minded discus- sion of refugee issues in the classroom is important for combatting negative attitudes and stereotypes toward refugees in their new communities (MacNevin, 2012). Community programming can provide opportunities to explore nontraditional language- learning methods, such as arts-based instruction, as well as to foster social development, cultural awareness, acceptance, and integration among residents and new arrivals (Mawani, 2014; Taylor & Sidhu, 2012). Economic and Family Situations Older refugee youth may need to contribute economically to family survival; almost two thirds (63%) of refugees in Canada under the age of 24 are employed (Statistics Canada, 2015a). Young refugee women with small children may suddenly find themselves the head of a household and needing to work (UNHCR, 2006). Citizenship and Immigration Canada (2011) reports that women head most single parent refugee families. This can mean a heavy responsibility for young refugee mothers who are often under 20 years old, an age when many in a host country such as Canada are relatively carefree and pursuing postsecondary educa- tion (Hatoss & Huijser, 2010; Mawani, 2014). Adding to the stress of forced migration, economic and family responsibilities can constitute a burden for refugee youth that erodes their mental health and coping abilities. Counsellors and therapists who

- 11. serve new refugees attest to the urgency of assisting them to deal with multiple and serious living-situation difficulties and to access necessary community support (Murray, Davidson, & Schweitzer, 2010; Nadeau & Measham, 2005). 309REFUGEE-YOUTH MENTAL HEALTH Education Another key area for supporting refugee youth is education and training. Some refugee children and adolescents have spent most if not all of their young lives in refugee camps or other living situations that have disrupted the normal education process (Guruge & Butt, 2015; MacNevin, 2012; Taylor & Sidhu, 2012). Thus, some refugee youth have low literacy skills in their own native language and no knowledge of their host country’s language (Woods, 2009). If they are of school age, they may face a daunting amount of work to catch up to their age mates. If they are past secondary school age, they may not meet requirements for post- secondary schools or training institutions and they may be pres- sured to take low-paying jobs to support family members and other dependents (Woods, 2009). Young refugees’ credentials or work experience may not be recognised in their host country (McBrien, 2005). This can be very stressful and, when added to the ordeal of forced migration, ensuing mental health problems are not surpris- ing (Iversen et al., 2014).

- 12. Gender Mental health clinicians and other professionals in European and North American countries may not be familiar with the par- ticular gender-role expectations and cultural norms among many refugee populations (Tastsoglou, Abidi, Bigham, & Lange, 2014). Furthermore, refugee girls and women have distinct needs and abilities that often go unrecognized because settlement policies and procedures were originally developed for uprooted men (UNHCR, 2006). Such uniformity in policy does not adequately account for the specific ways women may be affected by forced migration. For example, many refugee men are already accus- tomed to the role of financially providing for their families; how- ever, refugee women, including many who are very young, may face a new demand to generate family income while still main- taining their traditional child-rearing role (Tastsoglou et al., 2014). Often they receive little community or social support (Hatoss & Huijser, 2010). Mental health professionals may need to advocate for equitable policies within their agencies to support these young women (Berman et al., 2009; Ellis et al., 2010). In their Canadian study, Tastsoglou et al. (2014) found that young refugee women were victims of sexual violence at higher rates than men; however, they have often suffered from the loss of community protection and struggled to access services for gender-based violence they may have experienced in their home country. Refugee women and girls are also at risk of being victims of domestic violence in host

- 13. countries but may not feel safe to report such incidents; increasing awareness of safe ways for these women to report abuse is nec- essary (UNHCR, 2006). The need for culturally and gender- appropriate counselling is great; Guruge and Butt (2015) noted that young female refugees overall are diagnosed with mental health problems at higher rates than their male peers. Addressing the issues affecting young refugee women means developing an understanding of the intersectionality of young women’s identities (Beck, Williams, Hope, & Park, 2001). In this framework, strengths, abilities, barriers, and challenges are con- sidered through the multiple and intersecting variables of gender, class, race, family, language, trauma, work, and educational back- ground. By exploring the impact these interacting influences have on the experiences and identities of young refugee women, mental health therapists can tailor counselling to meet clients’ particular and contextualized needs. More research is needed on gender interactions. Counselling and mental health professionals can take a leader- ship role in supporting young refugee women. A perspective shift to identify refugee girls’ and women’s needs in the context of their existing abilities and strengths is critical for restoring a sense of agency and, ultimately, a sense of self to uprooted women.

- 14. Tastsoglou et al. (2014) suggested that connecting refugee women with opportunities to contribute their stories to public dialogues could positively impact societal discussions of their experiences. Developing and adapting mental health programming to accom- modate refugee girls’ and young women’s home and family re- sponsibilities can promote greater access to services. Increasing the availability and accessibility of services for young refugee women who have experienced sexual violence could increase their sense of safety in their new countries (Tastsoglou et al., 2014). Finally, mental health professionals are well positioned to advo- cate for refugee women and girls in their local communities (UNCHR, 2006). Advocacy can pose some challenges, however, because of the need to balance recognition of cultural gender roles and acknowledgement of structural barriers that may segregate and devalue female refugees in schools, agencies, and community settings. Many refugee women are dependent on family males who make all decisions for them and accompany them at all times; access to mental health services can thus be limited (Tastsoglou et al., 2014). Understanding Mental Health Challenges for Refugee Youth To understand the mental health challenges young refugees face, it is imperative to consider the multiple losses associated with being forced to leave a home country compounded with the stress and trauma that many refugees encounter either premigration or

- 15. along their journey to the host country. These difficulties distin- guish them from other immigrant populations, though the latter also experience multiple losses and some similar challenges (Hyndman, 2011). Guruge and Butt’s (2015) review of refugee- youth mental health in Canada noted that refugee youth experience many of the same postmigration stressors as other immigrants (e.g., institutional barriers, intergenerational conflict, and discrim- ination), but varying premigration hardships can influence refu- gees’ specific reactions to these stressors. Refugees’ experiences of trauma can include loss of family members or friends through death, disappearance, or displacement; witnessing or experiencing emotional and/or physical torture, severe injury, rape, bombings, or other forms of violence; camp imprisonment; fear for safety; hunger; homelessness; and loss of property (Yakushko, Watson, & Thompson, 2008). In addition, refugee youth may be forced to relocate to a new country without their parents, siblings, or other family members. Some must integrate into school or work systems without speaking the dominant language, whereas others may be held in detention centres for varying periods of time (Warr, 2010). Refugee youth have experienced different levels of conflict and, thus, their external experiences of trauma vary greatly. Also, internal experiences of trauma differ among individuals (Warr, 2010). In their review of youth-refugee mental health, Guruge, and Butt (2015) found that personal experiences of trauma were more

- 16. 310 MARSHALL, BUTLER, ROCHE, CUMMING, AND TAKNINT likely to lead to maladaptive symptoms than collective experiences such as war or staying in a refugee camp. Many refugee youth experience symptoms of post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) such as emotional numbness, disturbed sleep patterns, and flash- backs (Teodorescu et al., 2012). Unaccompanied refugee youth are most at risk for mental health challenges (Bean, Derluyn, Eurelings-Bontekoe, Broekaert, & Spinhoven, 2007; Derluyn, Mels, & Broekaert, 2009). Derluyn et al. (2009) reported that unaccompanied adolescents are especially likely to be exposed to premigration trauma and also to show more depressive symptoms upon resettlement. Unaccompanied minors show higher levels of PTSD symptoms than accompanied minors and minors from non- refugee populations (Huemer et al., 2009), as well as higher levels of anxiety (Derluyn & Broekaert, 2007). Other mental health issues that are common among refugee youth but may be mani- fested in unique ways are depression, low self-esteem, stress, anxiety, and conduct disorders (Guruge & Butt, 2015). Trauma associated with high-conflict areas such as Syria and parts of Africa typically involves multiple losses for youth, includ- ing family members, friends, education, property, work opportu- nities, and the sense of belonging. Thus, many refugees

- 17. experience grief during their resettlement (Craig, Sossou, Schnak, & Essex, 2008; Nickerson et al., 2014). Although grief is an expected response for those experiencing this magnitude of loss, some refugees experience prolonged or complicated grief, such that maladaptive responses to the losses persist (Prigerson et al., 2009). Psychologists and other mental health professionals working with refugee youth consistently identify a distinct theme of loss of home, belonging, and culture that emerges in therapy sessions (Warr, 2010). Refugee youth often experience a disrupted sense of self or identity that can erode self-esteem and independence (Allan, 2015). Migration can pose a significant threat to cultural identity, particularly if the home culture is discriminated against in the postmigration country (Pickren, 2014). Inman, Howard, Beaumont, and Walker (2007) found that cultural norms in a new country often make it difficult for refugees to maintain their natal culture, even when they attempt to do so. Moreover, forced mi- gration can lead to culture shock, a deep sense of isolation or lack of identification with a foreign home, which can have a negative impact on refugees’ sense of self. Ndengeyingoma, de Montigny, and Miron (2014) note that many refugee youth draw strength from family and religious values; however, negotiating the tension between these values and those of peers in the host country can be a challenge. Mental health professionals can assist refugee youth

- 18. by engaging them in discussions about how such value conflicts are affecting them and their families and by helping them to address and resolve tensions. Factors Influencing Mental Health Outcomes for Young Refugees Being a refugee does not in itself cause mental health problems; rather, a multitude of factors interact to influence individuals and families. Researchers have found a wide range of effects of mi- gration on refugees’ mental health (Ellis, Miller, Baldwin, & Abdi, 2011; Mawani, 2014). Some refugees experience mental health problems during and after resettlement, whereas others demon- strate positive functioning and resilience. Mawani (2014) articu- lates the interaction of factors. It is important to stress that, although refugees may be more likely to experience certain determinants and are therefore more at risk of certain mental health outcomes, they may not actually experience those outcomes, due to a combination of individual, family and community strengths. (p. 29) Therapists need to consider relevant migration contexts, as well as individual, family, and community factors, when assessing refugee mental health and planning interventions. Individual factors. Young refugees come to new countries with a wide range of experiences that influence their mental health.

- 19. Levels of stress, conflict, trauma, and coping are unique to each refugee in premigration, during migration, and upon resettlement. Not surprisingly, researchers have found that direct and indirect exposure to violence is associated with increased mental health problems for young refugees (Fazel, 2012; Yakushko et al., 2008). In their review, Fazel, Reed, Panter-Brick, and Stein (2012) also noted that personal injury sustained during premigration events was related to increased mental health concerns. Beyond these traumatic experiences associated with migration and resettlement, Joly (2011) has found that premigration mental health difficulties such as anxiety, depression, and exposure to nontraumatic but stressful life events impact refugees’ postmigration mental health. Family factors. Family history and disruptions to the family unit have an impact on young refugees’ mental health outcomes (Fazel et al., 2012). For example, children who are separated from their families pre- or postmigration are at increased risk of psy- chological problems (Bean et al., 2007; Hodes, Jagdev, Chandra, & Cunniff, 2008). Likewise, there is increased mental health risk for young refugees whose parents are missing, imprisoned, or cannot be contacted (Hjern, Angel, & Jeppson, 1998). Family support and cohesion are related to better mental health for young refugees (Kovacev & Shute, 2004; Rousseau, Drapeau, & Platt, 2004), as is parental mental health (Hjern et al., 1998). Economic circumstances within the family can also influence mental health

- 20. outcomes. Sujoldzić, Peternel, Kulenović, and Terzić (2006) found that parental worries about financial problems, a common occur- rence upon resettlement, can have an adverse effect on children’s mental health. Therapists who are counselling refugee youth need to have some understanding of family context and history to establish priorities in therapy. Community and societal level factors. It is important that refugee youth find positive connections and develop relationships in places where they feel welcome, such as in school and in their host communities. The extent to which refugees perceive them- selves as accepted or discriminated against within host countries is related to mental well-being (Fazel et al., 2012). Oppression and discrimination based on race, ethnicity, sex, religion, poverty, and employment status have a negative impact for these young people (Marsella & Ring, 2003; Yakushko et al., 2008). Research has identified a relationship between peer discrimination and low self-esteem, depression, and PTSD among young refugees (Sujoldzić et al., 2006). In contrast, perceived positive social support is related to improved psychological functioning (Kovacev & Shute, 2004). Therapists can help refugee youth establish rela- tionships in which they experience the sense of belonging that has

- 21. 311REFUGEE-YOUTH MENTAL HEALTH been found to protect against anxiety and depression (Fazel et al., 2012). Addressing Barriers to Engagement in Mental Health Services Despite experiencing disproportionately more mental health challenges than their host-country peers, refugee youth make sig- nificantly less use of mental health services than do nonrefugees and many who are in need go without support (Huang, Yu, & Ledsky, 2006). It is important that community and mental health referrals be aware of barriers to service faced by refugee youth and their families to develop strategies to overcome these challenges (Craig et al., 2008). The main barriers identified in the literature include distrust of authority, stigma, language and cultural differ- ences, and having other priorities. Distrust of Authority Interventions for refugee youth and their families must be de- veloped and delivered with attention to individuals’ experiences, together with their more general cultural history (Allan, 2015). Many refugees develop distrust of authorities after being victim- ized by governmental systems and other establishments. Some-

- 22. times the very organisations that were in place ostensibly to provide support and safety were, in fact, responsible for inflicting trauma (Ellis et al., 2011). Some refugees might be hesitant with helping professionals due to perceived power imbalances. Because of such potential for distrust, it is recommended that therapists devote increased time and effort to develop rapport and a sense of safety with refugee clients (Ehntholt & Yule, 2006; Hundley & Lambie, 2007). Ellis et al. (2011) suggest that enlisting input and help from other refugee families and the broader community to develop and deliver appropriate mental health services can assist in establishing trust. Young people may feel more comfortable if their families and/or community members are involved in mental health discus- sions and program planning. Although this type of collaboration may be rare, Ellis and colleagues (2011) argue that parent groups and outreach programs that commonly seek input from refugee families could be extremely valuable in creating effective, appro- priate, and trustworthy services. Stigma Refugee youth and their families may hesitate to seek counsel- ling services because of the stigma surrounding mental illness and those who seek this form of help (Osterman & de Jong, 2007; Palmer, 2006). For some families, help-seeking stigma could be

- 23. perceived as worse than enduring mental health problems with no support (Ellis et al., 2011). Some refugee cultures may not define mental illnesses in the same way they are conceptualised in host countries and some languages may not have the words to convey the adjustment difficulties young refugees experience (Ellis et al., 2011). Kira et al. (2014) found that internalized stigma surround- ing mental illness can exacerbate the negative impact of mental health problems; thus, the need for counsellors to address this issue with refugees who may be struggling is paramount. Rousseau et al. (2004) suggest that one strategy to diminish the stigma associated with mental illness is to embed mental health services in other acceptable forms of support. An example is the counselling services that are available in secondary and postsec- ondary educational settings (Guruge & Butt, 2015; Rousseau & Guzder, 2008). Refugee youth can receive support from a mental health professional while at school, rather than having an addi- tional commitment solely for the purpose of mental health. Fam- ilies may be more likely to view support from professionals in an educational setting in a positive light, compared with services from a mental health organisation. Community cultural organisations and outreach programs are other examples of support services that can include mental health information and promotional activities in their programming (Correa-Velez et al., 2010). Trusted com- munity leaders and members can also assist by emphasising the

- 24. importance of positive mental health and encouraging families to seek help when difficulties persist. Linguistic and Cultural Differences Language differences can constitute a considerable barrier be- tween refugees and host country mental health professionals. As- sessment and therapy sessions are often one-on-one encounters that require good language skills. Refugee youth may acquire a new language relatively quickly; their parents, however, who may need mental health services themselves or who have to provide consent for youth counselling, may not. This forms part of a larger pattern in which gaps exist between parents and children’s level of acculturation to the host country, which may lead to stress and conflict within the family (Hynie, Guruge, & Shakya, 2012). Services are rarely available in the language in which these fam- ilies are fluent and the refugee demographic changes constantly; counsellors need to be sensitive to refugees’ language proficiency and take time to ensure that they and their clients understand one another (Ellis et al., 2011). In their study of refugee families’ use of mental health services in Canada, Nadeau and Measham (2005) found that using inter- preters could address the need for both linguistic and cultural relevance in treatment. Translation can help facilitate communi- cation in therapy, however, having an extra person present affects the therapeutic relationship and can compromise confidentiality.

- 25. Moreover, given the wide diversity within and among refugee groups, it cannot be assumed that an interpreter will have a full cultural understanding of a refugee’s background, (Nadeau & Measham, 2005). Interpretation is a necessity in cases in which language barriers are significant, though translation of therapy terms and client experiences is not ideal (Ellis et al., 2011). Ellis and colleagues (2011) recommend that including community voices and cultural experts in the development and delivery of mental health services and training is essential and should be a priority in program design. Therapists can benefit from such cul- tural perspectives on delivering care in appropriate and relevant ways. Other Priorities A significant barrier for young refugees is that other resettle- ment needs may be seen as more urgent and pressing than mental health concerns (Codrington, Iqbal, & Segal, 2011). Refugees who seek counselling may be as much or even more concerned about basic needs such as food, shelter, and safety (Fazel et al., 2012). 312 MARSHALL, BUTLER, ROCHE, CUMMING, AND TAKNINT Where possible, mental health professionals can broaden their scope of care so that urgent resettlement needs are addressed together with mental health concerns (Codrington et al., 2011; Warr, 2010). Therapists can include attention to basic needs as part of their initial assessment and either take on an advocacy role

- 26. themselves or refer clients to additional services (Yule, 2002). Having mental health services located with or close to other health, family, and community services can facilitate a holistic approach to refugee support as well as make it easier for diverse clients to benefit from the services available. Another strategy to address multiple and pressing needs is to spend a significant portion of counselling sessions on fostering client strength and agency rather than focusing solely on premi- gration or migration experiences and problems (Murray et al., 2010). Psychologists and therapists need to use their professional judgment to establish priorities and the primacy of needs. Codrington et al. (2011) suggest that efforts to enhance positive social connections and employability may be more valuable during initial stages of resettlement than focusing primarily on past events. Good Practices in Counselling Refugee Youth The range, severity, and impact of problematic and traumatic experiences is different for each refugee youth; counselling psy- chologists and therapists need to assess multiple and contextual- ized dimensions of clients’ experiences and reactions (Shakya, Khanlou, & Gonsalves, 2010; Yakushko et al., 2008). Adjustment to a new community and culture requires significant new learning in social, linguistic, educational, and vocational spheres (Murray et al., 2010). Research and scholarly writing have identified several

- 27. recommended practices for effectively addressing short- and long- term mental health challenges among refugee youth: cultural com- petency, establishing trust and safety, recognising strengths, ex- tending counselling to the family unit, using creative approaches, and making use of mobile and online environments. Cultural Competency A key factor to effectively address the mental health needs of young refugees is providing culturally relevant services (Grothaus, McAuliffe, & Cragien, 2012; Sue, Zane, Nagayama Hall, & Berger, 2008; Yakushko et al., 2008). Culture includes a constel- lation of factors, including but not limited to race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, spirituality, and socioeconomic status that interact to form attitudes, beliefs, and values (Harris, Thoresen, & Lopez, 2007). A culturally competent therapist is self-aware and recognizes how cultural values, attitudes, and beliefs intersect with and influence the counselling process (Constantine, Hage, Kindaichi, & Bryant, 2007). For instance, what may be perceived as a strength or asset in one culture (e.g., individualism or inde- pendence) may be viewed as a deficit or problem in another culture (e.g., the collective good, or interdependence; Grothaus et al., 2012). There are also cultures within cultures; gender differences are noted to be particularly salient among refugee populations (Tastsoglou et al., 2014). Both therapists’ and clients’ cultures

- 28. affect the way counselling is explained and proceeds. Mental health counsellors should be mindful of ethnocentrism and make efforts to understand the client’s own conceptualisation of his or her strengths (Whalen et al., 2004). Avoiding culturally bound views of mental health leaves space for appreciating culturally distinct and appropriate notions of mental health and healing that could benefit the client (Miller, Kulkarni, & Kushner, 2006). Cultural competency in counselling requires that counsellors educate themselves about different worldviews (Ponterotto, Utsey, & Pedersen, 2006). This includes knowledge about the sociopo- litical contexts of refugee youth, including experiences of discrim- ination and other oppression. It is important for counsellors to be able to learn (either through research, education, or direct ques- tioning) what their clients perceive as strengths, as well as positive dimensions of their cultural groups, such as spirituality, storytell- ing, or being bilingual (Grothaus et al., 2012). Services should be developed with the refugees’ specific cultures in mind (Ehntholt & Yule, 2006). The diversity among refugees is such that therapists cannot be expected to know about all the particular cultures of potential clients; a broad understanding of refugee population issues and knowing how to access more specific information is foundational. Community cultural centre events, professional de- velopment workshops, and online webinars or courses are all

- 29. good resources for expanding cultural competency (Constantine et al., 2007; Grothaus et al., 2012). Pickren’s (2014) research found that refugees’ continued con- nection to their cultural identity is often a source of strength and resilience for them individually and within the family unit. Ther- apists can encourage the social and emotional support among family and community members that involves exploration of cul- tural, spiritual, and family beliefs, which can be a protective factor against mental health problems. Furthermore, counsellors can pay attention to whether clients begin to question or abandon their own cultural identity (which may be perceived as lower status in the host country) in an effort to fit in to the dominant culture (Yakushko et al., 2008). As families settle within their host coun- tries, parents may struggle to balance socializing their children within the new environment with maintaining the connection to their preimmigration culture (Pickren, 2014). Mental health pro- fessionals can engage refugee youth and families in exploring these acculturation tensions and address what it means to maintain connection to their cultural identity while adapting to a new one. Adopting a bicultural identity is often attractive to youth but of concern to parents and older relatives, (Kovacev & Shute, 2004). The notion of seeking psychological counselling for mental health concerns is not necessarily accepted by all cultures (Sue

- 30. et al., 2009). Some cultures may stigmatize those who express a need for counselling services, or they may believe the process is un- trustworthy or incompatible with their spiritual or religious beliefs (Osterman & de Jong, 2007). Others may simply not understand the purpose of counselling or the processes involved. Warr (2010) suggests that devoting time in session to explaining the counselling process can be beneficial for young refugee clients. Toporek (2012) recommends that this conversation be collaborative rather than prescriptive, such that therapist and client negotiate what will work for both parties. Establish Trust and Safety Within the Therapeutic Relationship The relationship between the client and therapist, referred to as the therapeutic alliance, is paramount for successful outcomes (Elvins & Green, 2008). A positive connection is particularly 313REFUGEE-YOUTH MENTAL HEALTH important with refugee clients, because their need to feel safe is understandably high (Guregård & Seikkula, 2014). Moreover, refugees may face uncertainty about factors such as legal status or income and thus experience insecurity and a threatened sense of safety (Van der Veer & Van Waning, 2004). To establish effective

- 31. therapeutic relationships with refugees, therapists should prioritize building trust and rapport and recognise that more time than usual may be required because of trust, language, and other issues. Warr (2010) suggested that professionals pay particular attention to helping refugee children and youth feel safe and secure. With refugees who have experienced trauma and conflict, it is important to consider emotional containment in the therapeutic relationship (Van der Veer & Van Waning, 2004). Young refugee clients may share horrific stories and their emotional reactions to them; the safety of the therapeutic relationship requires therapists to attend to appropriate containment of emotional intensity and not become traumatized themselves (Van der Veer & Van Waning, 2004). The foundational skills of empathy and positive regard are also crucial in establishing a positive therapeutic relationship; demonstrating these skills includes listening carefully to personal testimonies of adversity and reflecting an understanding of these stories (Murray et al., 2010). It is important for counsellors to pay close attention to the story of the referral process and assure that they fully understand the client’s reason for seeking counselling; a study by Codrington et al. (2011) suggested that a counsellor’s lack of understanding of how a refugee family arrived in counsel-

- 32. ling or who the identified client is may be a root cause of unsuc- cessful therapy. Maintaining hope is valuable in the fostering of an effective and change-producing therapeutic relationship (Codrington et al., 2011). A counsellor’s sense of hope can affect the client’s; bal- ancing it with realistic expectations is a goal for therapists. Un- derstanding a refugee client’s priorities and capabilities contribute to fostering hope and motivation for change. Recognise Resiliency and Strengths All too often, well-intentioned programs oriented toward refu- gee youth “fail to recognise and build on the considerable re- sources these youth bring to their new country” (Correa-Velez et al., 2010, p. 1399). Psychologists and counselling professionals are encouraged to adopt a strength-based approach, focusing on knowledge and abilities youth have acquired through previous experiences and on the agency they have within their own lives, leveraging such assets to help overcome problems. While refugee youths’ risk of mental health difficulties is significant, they also possess resiliency and strengths that can help them adjust success- fully in host countries (Eide & Hjern, 2013). One study investi- gating mental health outcomes for refugees found that almost half the sample did not show symptoms of complex prolonged grief or PTSD, but rather, recovered from their experiences of trauma and loss naturally over time (Nickerson et al., 2014). Yakushko and

- 33. colleagues (2008) described how young refugees showed resil- ience in managing the stress of relocation. Other research has shown that refugees demonstrate considerable well-being in areas of psychological, social, and economic adaptation (Coughlan & Owens-Manley, 2006). These authors concluded that positive ad- aptation after very difficult experiences is prevalent; counselling therapists should not assume that problems with adjustment will occur for all or even most refugee youth. Researchers and counselling therapists increasingly call for a shift away from emphasising experiences and symptoms of trauma and PTSD and more toward a positive holistic approach that highlights the inherent strengths and coping abilities of refugees (Murray et al., 2010; Papadopoulos, 2007). Miller et al. (2006) suggested incorporating culturally appropriate mental health ex- planations and interventions; imposing western definitions of psy- chological and psychosocial well-being and impairment can be misleading and even harmful to refugee populations. Refugees themselves report that it would be helpful for therapists to focus on family issues, social integration, and grieving (Miller et al., 2006). Strengths-based practices support positive growth and change among refugee populations (Papadopoulos, 2007). Mental health professionals can use therapy approaches and interventions that highlight personal strengths and leadership skills as well as com- munity leadership and cultural wisdom (Murray et al., 2010; Yakushko et al., 2008). As Yakushko et al. (2008) observe, strengths-focused approaches build on refugees’ hope and opti-

- 34. mism as momentum for positive growth and change. Positive youth development (PYD) is a strengths-based ap- proach to working with young people that aims to guide youth so they can mature into well-adjusted adults; this approach has been used successfully to inform the design of programs for refugee youth (Morland, 2007). Developed to counter deficit-focused con- ceptualisations of young people, PYD begins with the view that all youth have inner strengths and resources that supportive adults can capitalize on and nurture (Damon, 2004). Recommended PYD- implementation practices to support refugee youth include forming partnerships with refugee communities, engaging with youths’ family members, supporting and encouraging bicultural/bilingual staff, strengthening ethnic and bicultural identity, encouraging youth leadership, ensuring academic support, and fostering con- nections with community organisations and businesses (Morland, 2007). Many individuals who encounter hardship, including trauma, notice areas of growth or positive change that take place after their difficult experiences. Tedeschi and Calhoun (2004) refer to this phenomenon as posttraumatic growth (PTG), defined as follows. The experience of individuals whose development, at least in some areas, has surpassed what was present before the struggle with crises

- 35. occurred. The individual has not only survived, but has experienced changes that are viewed as important, and that go beyond what was the previous status quo. (p. 4) Tedeschi and Calhoun (2004) stress that this growth arises from responses and situations in the aftermath of the trauma, not from the trauma itself. The concept of positive change in the aftermath of trauma is particularly relevant for refugee youth. Teodorescu et al. (2012) explored the presence of PTG for individuals with a refugee background and found that most participants reported greater appreciation for life, positive spiritual change, and increased per- sonal strength since migration. Further, social support has been found to increase refugees’ reports of PTG (Kroo & Nagy, 2011). The notion of PTG does not suggest that refugees are better off in some way because of their extreme challenges, but rather, that many can find positive things to say about how their lives have 314 MARSHALL, BUTLER, ROCHE, CUMMING, AND TAKNINT changed. Keeping this in mind, counsellors and mental health therapists should look for current and previous indicators of pos- itive growth, and encourage their refugee clients to elaborate on the strengths they believe they possess or are developing.

- 36. Extend Counselling Services to the Family Unit Relationships within refugee families are put under stress by the members’ migration and premigration experiences, as well as by the ordeal of resettling in a new country. Youth may find the normal challenges of adolescence exacerbated by trauma and hard- ships; for the same reasons, parents may find it difficult to fulfill their usual roles (Codrington et al., 2011). Because most refugee families have a history of shared experience, providing mental health services to the entire family, rather than just to one specified individual, may be beneficial. Björn, Boden, Sydsjo, and Gustafsson (2013) suggest that even a few counselling sessions that include parents and siblings can be beneficial for refugee youth who suffer from mental health problems. Young refugees who do not necessarily demonstrate symptoms of psychopathology or psychological difficulties may still benefit from counselling sessions that include their family members. Björn and colleagues (2013) cautioned that decisions to include family members in therapy should be discussed collaboratively with young refugee clients together with an exploration of expectations, cultural norms, and possible outcomes that could affect family relation- ships or progress in therapy. Refugees have left behind aspects of their culture and support systems they may have relied upon during difficult times; thus, the family unit becomes more important (Voulgaridou, Papadoupoulos, & Tomaras, 2006). Despite losses, refugee youth and their families

- 37. have the ability to adapt and meet new challenges. Family therapy can foster strengths and build the nuclear or extended family as a reliable support in the new country (Hjern & Jeppson, 2005). Use Creative and Complementary Approaches and Interventions Creative therapy approaches and methods appeal to young peo- ple, enhance expression, build trust, aid communication, and help youth process emotions (Warr, 2010). Offering a therapeutic pro- cess that is flexible and creative can be beneficial for youth who are not familiar with counselling or mental health practices. Non- verbal and arts-based therapies provide opportunities to explore past or present events and trauma impacts with clients whose host-language abilities are limited (Marshall, 2009; Rousseau & Guzder, 2008). Two Canadian studies using expressive arts and psychodrama found these approaches effective in assisting refugee youth in processing feelings and thoughts in a safe environment (Rousseau et al., 2004; Rousseau & Guzder, 2008). Structured interactions with peers at school and in the commu- nity can provide opportunities for refugee youth to develop social skills and learn the ways of the host country, as well as their local contexts. Whether as a complement to therapy or by itself, partic- ipation in extracurricular and community activities can help in- crease self-esteem, prevent social isolation, and build social net-

- 38. works (Stewart, 2014). Programs in sports, music, dance, cooking, arts and theatre, as well as homework clubs, educational field trips, and employment support can help refugee youth build positive relationships and a sense of community with other youth and supportive adults (Mawani, 2014). Edge, Newbold, and McKeary (2014) found that refugee youth in their Canadian sample were likely to take advantage of such opportunities if they were offered. School and community professionals are well-placed to encourage and monitor social interactions among refugees and their peers in these types of activities. Sports have long been advocated as a globally recognised means for promoting social engagement, acceptance, and acculturation for refugee and immigrant youth (Forde, Lee, Mill, & Frisby, 2015; Oliff, 2008; Spaaij, 2013). Sports activities and programs offer opportunities for improving refugee youths’ integration, growth, well-being, and sense of belonging, and for providing a sense of normalcy in their lives. At their best, sports can promote connections among refugee and host-country youth, families, and communities; critics, however, have also pointed to negative fac- tors that need to be addressed, such as participation barriers, exclusion, and marginalization (Spaaij, 2015). There are mixed views on whether sports and other activities should involve groups of a single ethnic background or include youth from diverse backgrounds. Some research has revealed that having diverse

- 39. backgrounds fosters cross-cultural awareness and positive relation- ships among refugee youth and their nonrefugee peers (Oliff, 2008); other research has found that refugee youth feel more comfortable and willing to participate when they are among peers from a similar background (Spaaij, 2013). Gender-role expecta- tions and strictures are a barrier for some young refugee women’s participation in sports, unless all-female teams or activities are made available (Spaaij, 2015). Choice is not always possible; supporting adults can assist refugee youth and their families to sensitively explore the options, benefits, and challenges of sports participation (Ontario Council of Agencies Serving Immigrants, 2006). The potential mental health benefits of social and community interactions and activities for refugee and host-country youth needs to be underscored (Forde et al., 2015; Ontario Council, 2006). Sports and community programs also fill a mental health- problem-prevention role by focusing on cooperation, social devel- opment, and leadership abilities (Forde et al., 2015; Spaaij, 2015). More research and program evaluation are needed on the impacts of educational, social, and sports participation on refugee youth mental health. Mobile Connections and Online Counselling As is the case among their nonrefugee peers, almost all refugee youth regularly use mobile technologies and social networks (Robertson, Wilding, & Gifford, 2016). Mobile communication helps youth maintain vital connection to dispersed family

- 40. members and friends; such connection is a key aspect of positive mental health. In resettlement contexts, access to tele-mental health ser- vices, e-counselling, online mental health-promotion resources, and apps offer new possibilities for a range of mental health support that is particularly attractive to youth (Robertson et al., 2016). Mobile technologies have the potential to improve access to mental health services for refugee populations, reduce stigma, and improve quality of health care (Mucic, Hilty, & Yellowlees, 2016). For youth who have fled persecution and who may have other histories that engender mistrust of government services and au- 315REFUGEE-YOUTH MENTAL HEALTH thorities, mobile phone mental health support is an important re- source offering both anonymity and immediacy (Mucic et al., 2016). Research and evaluation of online mental health services have become complicated by new and rapidly developing online plat- forms, tools, and apps (Mucic et al., 2016). Although youth use online and mobile services with great ease, some research has suggested that outcomes are best when technology augments or enhances in-person services (Knight & Hunter, 2013). An inter- esting point for service providers, Knight and Hunter (2013) iden- tified a gap between how youth engage in mobile technologies for mental health support and how organisations (and youth

- 41. workers) engage with and are comfortable using these same tools. Mental health professionals are encouraged to seek training opportunities in the complementary use of online and mobile tools in counsel- ling. Summary and Future Directions Counselling psychologists and other mental health professionals have vital knowledge and skills that are needed to support the healing and positive development of refugee youth. Key consid- erations when working with this population involve assessing need priorities, language, and acculturation levels. Individual, family, and community factors will have influenced the young people’s responses to the multiple losses and disrupted identity they expe- rienced before, during, and after migration. An understanding of the youth’s economic, family, and educational situation is impor- tant for mental health clinicians in assessing problems to be addressed. Gender is a particular element of potential difference and conflicting values; the intersectionality of young refugee women’s identities is a critical focus for therapy. Although chal- lenges such as fulfilling basic needs and barriers such as mistrust, stigma, and language/cultural differences can prevent or limit access to mental health support and its benefits for refugee youth, we have identified strategies and tools through the studies in this review that can help refugees overcome these barriers.

- 42. Refugee youth come from diverse backgrounds and have par- ticular needs linked to their situations; however, the research findings covered in this review point to several principles and practices that can help mental health service providers deliver appropriate and effective support for these young people. Cultural competency is essential, as recognised in professional codes of ethics and scope of practice guidelines. Establishing trust and safety as part of the therapeutic alliance is another key aspect when counselling refugee youth. A number of researchers have empha- sised the importance of recognising strengths and resiliency among refugee youth while still acknowledging the incidence of PTSD, depression, prolonged grief, and other psychological disorders among this population. Depending on the youth’s particular family context, it may be advisable to extend counselling to the family unit. Using creative therapy techniques and approaches and making use of mobile and online environments can expand the opportunities to engage refugee youth in mental health support that fits their particular circumstances. Evaluation and research are needed to assess the effectiveness of specific approaches and interventions. In their scoping review on youth refugee mental health, Guruge and Butt (2015) found only 17 articles on the topic in the previous 23 years. They recommend more research to gain a holistic picture of refugee youth mental health, including prevalence rates, pre- and postmigration factors, use of mental health services, and family dynamics. Gender-related mental health needs and inter- ventions are also seen as a priority, as is longitudinal research

- 43. to assess change over time in resettlement. School and community programs and activities that bring refugee and host-country youth together show great potential for mental health support and pro- motion; additional research could identify particular elements or program approaches that are effective. More cross-disciplinary studies about refugee youth mental health risk and protective factors, coping styles, effective therapy interventions, and re- sponses to treatment will inform research, clinical practice, and policy spheres. Intended for a broad audience, the goal of this review paper was to provide an overview of youth refugee mental health issues and practices; space precluded in-depth discussion or application to specific regional contexts. A further limitation, also related to space, was a lack of research methodology detail that would have enabled comparison among the studies. In summary, refugee youth arrive in host countries with expe- riences and histories of loss, trauma, uncertainty, and upheaval. Although their premigration context and migration journeys may place them at greater risk for mental health problems, they also settle in their new homes with skills, abilities, and hope. Mental health counsellors and therapists have a key role to play in assist- ing these young refugees to overcome mental health difficulties and realise their potential in their new environments. Résumé La crise mondiale de la migration a donné lieu à l’arrivée d’un nombre sans précédent de réfugiés au Canada et dans d’autres

- 44. pays. Un tiers de ces réfugiés sont des jeunes, qui sont accompa- gnés de leur famille ou qui sont seuls. Bien que les circonstances particulières varient énormément, ces derniers ont besoin d’aide pour l’apprentissage de la langue, l’éducation et l’adaptation à leur pays d’adoption; un grand nombre d’entre eux ont aussi besoin de services en santé mentale. Cet article de synthèse est axé sur les problèmes de santé mentale et les difficultés que vivent les jeunes réfugiés, ainsi que sur les pratiques de counseling qui se sont révélées efficaces auprès de ce groupe. Très peu de recherches se sont concentrées sur la santé mentale des jeunes réfugiés au Canada. Les études citées proviennent du Canada ainsi que des États-Unis, d’Australie et de pays d’Europe qui présentent de nombreuses similitudes dans leurs façons de traiter les dossiers et les difficultés concernant le counseling en santé mentale et la psychothérapie. L’article fait un compte rendu de la situation des jeunes réfugiés, suivi d’une description des problèmes et des difficultés en santé mentale qui leur sont propres, et d’une discus- sion sur les obstacles à l’engagement des services en santé men- tale, puis des suggestions de pratiques de counseling efficaces parmi cette population. L’article se termine par un sommaire des principaux résultats tirés de la littérature et par des suggestions de recherches futures en vue de combler les lacunes dans les connais- sances sur le sujet. Étant donné les nombreux obstacles que con- naissent les jeunes réfugiés avant leur arrivée, durant leur

- 45. déplace- ment et après leur installation dans un pays d’accueil, on ne peut s’étonner du fait qu’ils présentent des problèmes de santé mentale. En dépit de ces difficultés, ces jeunes gens font preuve 316 MARSHALL, BUTLER, ROCHE, CUMMING, AND TAKNINT d’adaptabilité, de persévérance et de résilience. L’appui de pro- fessionnels de la santé mentale qui reconnaissent leurs forces et leurs aptitudes contribuera à leur rétablissement et les aidera à s’adapter positivement à leur nouveau pays. Mots-clés : santé mentale des jeunes réfugiés, revue sur la santé mentale des jeunes réfugiés, jeunes réfugiés ayant des problèmes de santé mentale, counseling pour les jeunes réfugiés, pratiques en santé mentale pour les jeunes réfugiés. References Allan, J. (2015). Reconciling the ‘psycho-social/structural’ in social work counselling with refugees. British Journal of Social Work, 45, 1699 – 1716. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcu051 Bean, T., Derluyn, I., Eurelings-Bontekoe, E., Broekaert, E., & Spinhoven, P. (2007). Comparing psychological distress, traumatic stress reactions,

- 46. and experiences of unaccompanied refugee minors with experiences of adolescents accompanied by parents. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 195, 288 –297. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.nmd.0000243751 .49499.93 Beck, E., Williams, I., Hope, L., & Park, W. (2001). An intersectional model: Exploring gender with ethnic and cultural diversity. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work: Innovation in Theory, Research & Practice, 10, 63– 80. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J051v10n04_04 Berman, H., Mulcahy, G. A., Forchuk, C., Edmunds, K. A., Haldenby, A., & Lopez, R. (2009). Uprooted and displaced: A critical narrative study of home- less, Aboriginal, and newcomer girls in Canada. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 30, 418 – 430. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01612840802624475 Björn, G. J., Boden, C., Sydsjo, G., & Gustafsson, P. A. (2013). Brief family therapy for refugee children. The Family Journal, 21, 272–278. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1066480713476830 Citizenship and Immigration Canada. (2011). Evaluation of government- assisted refugees (GAR) and resettlement assistance program (RAP). Retrieved from

- 47. http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/resources/evaluation/gar- rap/section3.asp Citizenship and Immigration Canada. (2016a). Quarterly administrative data release: Canada. Permanent and temporary residents, Q4 2010 to Q5 2015. Retrieved from http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/resources/ statistics/data-release/2015-Q4/index.asp Citizenship and Immigration Canada. (2016b). Top 10 source countries: Refugee claims at all offices (in persons). Retrieved from http://open. canada.ca/data/en/dataset/d8599fcc-2822-4a3f-b7c8- b92ce44856bb Codrington, R., Iqbal, A., & Segal, J. (2011). Lost in translation? Embrac- ing the challenges of working with families from a refugee background. ANZJFT: Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 32, 129 –143. http://dx.doi.org/10.1375/anft.32.2.129 Constantine, M. G., Hage, S. M., Kindaichi, M. M., & Bryant, R. M. (2007). Social justice and multicultural issues: Implications for the practice and training of counselors and counseling psychologists. Jour- nal of Counseling & Development, 85, 24 –29. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ j.1556-6678.2007.tb00440.x

- 48. Correa-Velez, I., Gifford, S. M., & Barnett, A. G. (2010). Longing to belong: Social inclusion and well-being among youth with refugee backgrounds in the first three years in Melbourne, Australia. Social Science & Medicine, 71, 1399 –1408. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j .socscimed.2010.07.018 Coughlan, R., & Owens-Manley, J. (2006). Bosnian refugees in America: New communities, new cultures. New York, NY: Springer Science. Craig, C. D., Sossou, M., Schnak, M., & Essex, H. (2008). Complicated grief and its relationship to mental health and well-being among Bosnian refugees after resettlement in the United States: Implications for prac- tice, policy, and research. Traumatology, 14, 103–115. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1177/1534765608322129 Damon, W. (2004). What is positive youth development? Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 591, 13–24. http:// dx.doi.org/10.1177/0002716203260092 Derluyn, I., & Broekaert, E. (2007). Different perspectives on emotional and behavioural problems in unaccompanied refugee children and ado- lescents. Ethnicity & Health, 12, 141–162.

- 49. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/ 13557850601002296 Derluyn, I., Mels, C., & Broekaert, E. (2009). Mental health problems in separated refugee adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 44, 291– 297. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.07.016 Edge, S., Newbold, K. B., & McKeary, M. (2014). Exploring socio-cultural factors that mediate, facilitate, & constrain the health and empowerment of refugee youth. Social Science & Medicine, 117, 34 – 41. http://dx.doi .org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.07.025 Ehntholt, K. A., & Yule, W. (2006). Practitioner review: Assessment and treatment of refugee children and adolescents who have experienced war-related trauma. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47, 1197–1210. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01638.x Eide, K., & Hjern, A. (2013). Unaccompanied refugee children: Vulnera- bility and agency. Acta Paediatrica: Nurturing the Child, 102, 666 – 668. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/apa.12258 Ellis, B. H., MacDonald, H. Z., Klunk-Gillis, J., Lincoln, A., Strunin, L., & Cabral, H. J. (2010). Discrimination and mental health among Somali refugee adolescents: The role of acculturation and gender.

- 50. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 80, 564 –575. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j .1939-0025.2010.01061.x Ellis, B. H., Miller, A. B., Baldwin, H., & Abdi, S. (2011). New directions in refugee-youth mental health services: Overcoming barriers to engage- ment. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 4, 69 – 85. http://dx.doi .org/10.1080/19361521.2011.545047 Elvins, R., & Green, J. (2008). The conceptualization and measurement of therapeutic alliance: An empirical review. Clinical Psychology Review, 28, 1167–1187. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2008.04.002 Evans, R., Lo Forte, C., & McAslan Fraser, E. (2013). UNCHR’s engage- ment with displaced youth. Retrieved from http://www.unhcr.org/ 513f37bb9 .pdf Fazel, M., Reed, R. V., Panter-Brick, C., & Stein, A. (2012). Mental health of displaced and refugee children resettled in high-income countries: Risk and protective factors. The Lancet, 379, 266 –282. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60051-2 Fazel, M., Wheeler, J., & Danesh, J. (2005). Prevalence of serious mental

- 51. disorder in 7000 refugees resettled in Western countries: A systematic review. The Lancet, 365, 1309 –1314. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140- 6736(05)61027-6 Forde, S. D., Lee, D. S., Mills, C., & Frisby, W. (2015). Moving towards social inclusion: Manager and staff perspectives on an award winning community sport and recreation program for immigrants. Sport Man- agement Review, 18, 126 –138. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2014.02 .002 Government of Canada. (2016). #WelcomeRefugees: Key figures. Retrieved from http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/refugees/welcome/milestones.asp Grothaus, T., McAuliffe, G., & Craigen, L. (2012). Infusing cultural competence and advocacy into strengths-based counseling. Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 51, 51– 65. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/j.2161- 1939.2012.00005.x Guregård, S., & Seikkula, J. (2014). Establishing therapeutic dialogue with refugee families. Contemporary Family Therapy, 36, 41–57. http://dx .doi.org/10.1007/s10591-013-9263-5 Guruge, S., & Butt, H. (2015). A scoping review of mental health issues

- 52. and concerns among immigrant and refugee youth in Canada: Looking back, moving forward. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 106, e72– e78. http://dx.doi.org/10.17269/cjph.106.4588 http://journal.cpha.ca/ index.php/cjph/article/view/4588/3032 317REFUGEE-YOUTH MENTAL HEALTH http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcu051 http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.nmd.0000243751.49499.93 http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.nmd.0000243751.49499.93 http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J051v10n04_04 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01612840802624475 http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1066480713476830 http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/resources/evaluation/gar- rap/section3.asp http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/resources/evaluation/gar- rap/section3.asp http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/resources/statistics/data- release/2015-Q4/index.asp http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/resources/statistics/data- release/2015-Q4/index.asp http://open.canada.ca/data/en/dataset/d8599fcc-2822-4a3f-b7c8- b92ce44856bb http://open.canada.ca/data/en/dataset/d8599fcc-2822-4a3f-b7c8- b92ce44856bb http://dx.doi.org/10.1375/anft.32.2.129 http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2007.tb00440.x http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2007.tb00440.x http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1534765608322129 http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1534765608322129 http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0002716203260092

- 54. Journal of Counseling & Development, 85, 3–13. http://dx.doi.org/10 .1002/j.1556-6678.2007.tb00438.x Hatoss, A., & Huijser, H. (2010). Gendered barriers to educational oppor- tunities: Resettlement of Sudanese refugees in Australia. Gender and Education, 22, 147–160. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09540250903560497 Hjern, A., Angel, B., & Jeppson, O. (1998). Political violence, family stress and mental health of refugee children in exile. Scandinavian Journal of Social Medicine, 26, 18 –25. Hjern, A., & Jeppson, O. (2005). Mental health care for refugee children in exile. In D. Ingleby (Ed.), Forced migration and mental health: Rethink- ing the care of refugees and displaced persons (pp. 115–128). New York, NY: Springer. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/0-387-22693-1_7 Hodes, M., Jagdev, D., Chandra, N., & Cunniff, A. (2008). Risk and resilience for psychological distress amongst unaccompanied asylum seeking adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49, 723–732. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01912.x Huang, Z. J., Yu, S. M., & Ledsky, R. (2006). Health status and health service access and use among children in U.S. immigrant

- 55. families. American Journal of Public Health, 96, 634 – 640. http://dx.doi.org/10 .2105/AJPH.2004.049791 Huemer, J., Karnik, N. S., Voelkl-Kernstock, S., Granditsch, E., Dervic, K., Friedrich, M. H., & Steiner, H. (2009). Mental health issues in unaccompanied refugee minors. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 3, 13–23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1753-2000- 3-13 Hundley, G., & Lambie, G. W. (2007). Russian speaking immigrants from the commonwealth of independent states in the United States: Implications for mental health counselors. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 29, 242–258. http://dx.doi.org/10.17744/mehc.29.3.34016u53586q4016 Hyndman, J. (2011). Summary on resettled refugee integration in Canada. Retrieved from http://www.unhcr.ca/wp- content/uploads/2014/10/RPT- 2011-02-resettled-refugee-e.pdf Hynie, M., Guruge, S., & Shakya, Y. B. (2013). Family relationships of Afghan, Karen and Sudanese refugee youth. Canadian Ethnic Studies, 44, 11–28. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/ces.2013.0011 Inman, A. G., Howard, E. E., Beaumont, R. L., & Walker, J. L. (2007).

- 56. Cultural transmission: Influence of contextual factors in Asian Indian immigrant parents’ experiences. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54, 93–100. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.54.1.93 Iversen, V., Sveaass, N., & Morken, G. (2014). The role of trauma and psychological distress on motivation for foreign language acquisition among refugees. International Journal of Culture and Mental Health, 7, 59 – 67. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17542863.2012.695384 Joly, M.-P. (2011). Armed conflict exposure, the proliferation of stress, and the mental health adjustment of immigrants in Canada (Working Paper). Retrieved from http://munkschool.utoronto.ca/cphs/wp- content/uploads/ 2012/12/CPHS-Joly-2010-11.pdf Kira, I. A., Lewandowski, L., Ashby, J. S., Templin, T., Ramaswamy, V., & Mohanesh, J. (2014). The traumatogenic dynamics of internalized stigma of mental illness among Arab American, Muslim, and refugee clients. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 20, 250 –266. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1078390314542873 Knight, K., & Hunter, C. (2013). Using technology in service delivery to families, children and young people (CFCA Paper No. 17). Retrieved

- 57. from https://aifs.gov.au/cfca/sites/default/files/cfca/pubs/papers/a145 634/ cfca17.pdf Kovacev, L., & Shute, R. (2004). Acculturation and social support in relation to psychosocial adjustment of adolescent refugees resettled in Australia. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 28, 259 – 267. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01650250344000497 Kroo, A., & Nagy, H. (2011). Posttraumatic growth among traumatized Somali refugees in Hungary. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 16, 440 – 458. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2011.575705 MacNevin, J. (2012). Learning the way: Teaching and learning with and for youth from refugee backgrounds on Prince Edward Island. Canadian Journal of Education, 35, 48 – 63. Marsella, A. J., & Ring, E. (2003). Human migration and immigration: An overview. In L. L. Adler & U. P. Gielen (Eds.), Migration: Immigration and emigration in international perspective (pp. 3–22). Westport, CT: Praeger. Marshall, A. (2009). Mapping approaches to phenomenological and nar- rative data analysis. Encyclopaideia: Rivista di Fenomenologia,

- 58. Peda- gogia, Formazione, 25, 9 –24. Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50, 370 –396. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0054346 Mawani, F. N. (2014). Social determinants of refugee mental health. In L. Simich & L. Andermann (Eds.), Refuge and resilience: Promoting resilience and mental health among resettled refugees and forced mi- grants (pp. 27–50). New York, NY: Springer. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/ 978-94-007-7923-5_3 McBrien, J. L. (2005). Educational needs and barriers for refugee students in the United States: A review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 75, 329 –364. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/00346543075003329 McKenzie, K. J., Tuck, A., & Agic, B. (2014). Mental healthcare policy for refugees in Canada. In L. Simmich & L. Andermann (Eds.), Refuge and resilience: Promoting resilience and mental health among resettled refugees and forced migrants (pp. 181–194). New York, NY: Springer Science and Business. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007- 7923-5_12 Miller, K. E., Kulkarni, M., & Kushner, H. (2006). Beyond

- 59. trauma-focused psychiatric epidemiology: Bridging research and practice with war- affected populations. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 76, 409 – 422. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.76.4.409 Morland, L. (2007). Promising practices in positive youth development with immigrants and refugees. Prevention Researcher, 14, 18 – 20. Mucic, D., Hilty, D. M., & Yellowlees, P. M. (2016). E-mental health toward cross-cultural populations worldwide. In D. Mucic & D. M. Hilty (Eds.), e-Mental Health (pp. 77–91). New York, NY: Springer. http:// dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20852-7_5 Murray, K. E., Davidson, G. R., & Schweitzer, R. D. (2010). Review of refugee mental health interventions following resettlement: Best prac- tices and recommendations. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 80, 576 –585. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01062.x Nadeau, L., & Measham, T. (2005). Immigrants and mental health ser- vices: Increasing collaboration with other service providers. Canadian Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Review, 14, 73–76. Ndengeyingoma, A., de Montigny, F., & Miron, J.-M. (2014). Develop-

- 60. ment of personal identity among refugee adolescents: Facilitating ele- ments and obstacles. Journal of Child Health Care, 18, 369 – 377. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1367493513496670 Nickerson, A., Liddell, B. J., Maccallum, F., Steel, Z., Silove, D., & Bryant, R. A. (2014). Posttraumatic stress disorder and prolonged grief in refugees exposed to trauma and loss. BMC Psychiatry, 14, 106. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-106 Oliff, L. (2008). Playing for the future: The role of sport and recreation in supporting refugee young people to ‘settle well’ in Australia. Youth Studies Australia, 27, 52– 60. Ontario Council of Agencies Serving Immigrants. (2006). Inclusive model for sports and recreation programming for immigrant and refugee youth. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Author. Osterman, J. E., & de Jong, J. T. V. M. (2007). Cultural issues in trauma. In M. J. Friedman, T. M. Keane, & P. A. Resick (Eds.), Handbook of PTSD: Science and practice (pp. 425– 446). New York, NY: Guilford Press. Palmer, D. (2006). Imperfect prescription: Mental health perceptions,