This document provides an overview of wireless communication technologies for IoT networks. It evaluates long range and short range technologies like Sigfox, LTE-M, and ZigBee in terms of capacity and coverage. It also analyzes the performance of a ZigBee network in indoor and outdoor scenarios with interference from WiFi and Bluetooth. Outdoor tests show fading signals have the biggest impact on path loss, increasing it by 14.8 dB at 0.5 meter antenna heights. Indoor interference from WiFi results in only a 10% packet loss ratio in the worst case scenario of 20 meters between nodes and 5 concrete walls.

![FIGURE 1 SENSOR NODE ARCHITECTURE 5

FIGURE 2 SENSOR NETWORK ARCHITECTURE/STAR TOPOLOGY 6

FIGURE 3 WSN LOCAL AREA COVERAGE AND WIDE AREA COVERAGE 7

FIGURE 4 ZIGBEE NETWORK TOPOLOGY 9

FIGURE 5 ZIGBEE PROTOCOL STACK 9

FIGURE 6 BLUETOOTH LE STACK 12

FIGURE 7 GLOBAL MOBILE DATA TRAFFIC, 2014-2019 [34] 14

FIGURE 8 GSM NETWORK ARCHITECTURE 16

FIGURE 9 GPRS ARCHITECTURE 17

FIGURE 10 UMTS NETWORK ARCHITECTURE 18

FIGURE 11 LTE NETWORK ARCHITECTURE 20

FIGURE 12 LPWA NETWORK DEPLOYMENT SCENARIOS 23

FIGURE 13 IOT ARCHITECTURE 24

FIGURE 14 MESSAGING PATTERN 25

FIGURE 15 WEIGHTLESS NETWORK ARCHITECTURE 27

FIGURE 16 SIGFOX USE CASE 28

FIGURE 17 PROTOCOL STACK AND ASSOCIATED PROTOCOLS FOR EACH LAYER 31

FIGURE 18 BER FOR BPSK AND IN RAYLEIGH AND AWGN CHANNELS 35

FIGURE 19 BER FOR A BPSK AND QPSK SIGNAL IN AN AWGN CHANNEL 36

FIGURE 20 FREE SPACE PATH LOSS IN 900 MHZ AND 2.4 GHZ BANDS 38

FIGURE 21 OKUMURA HATA PATH LOSS MODEL FOR 900 MHZ FOR SEVERAL SCENARIOS WITH DIFFERENT

ANTENNA HEIGHTS [M] 39

FIGURE 22 OKUMURA HATA PATH LOSS MODEL FOR 2.4 GHZ FOR SEVERAL SCENARIOS WITH DIFFERENT

ANTENNA HEIGHTS [M] 39

FIGURE 23 INDOOR PATH LOSS FOR 900 MHZ AND 2.4 GHZ BANDS 41

FIGURE 24 RANGE COMPARED WITH DATA RATE CONSIDERING DIFFERENT TECHNOLOGIES 43

FIGURE 25 COVERAGE ENHANCEMENTS FOR REL-13 LTE M2M DEVICES 47

FIGURE 27 WIRED CONNECTION FROM METERING DEVICE TO RPI 53

FIGURE 28 WIRELESS CONNECTIVITY BETWEEN RPI AND SENSOR 54

FIGURE 29 DATA ACQUISITION DATABASE [13] 55

FIGURE 30 SYSTEM OVERVIEW 56

FIGURE 31 ZIGBEE TEST CONDITIONS 59

FIGURE 32 X-CTU DEVICE SELECTION 60

FIGURE 33 CLUSTER ID 0X12 MODE OF OPERATION 60

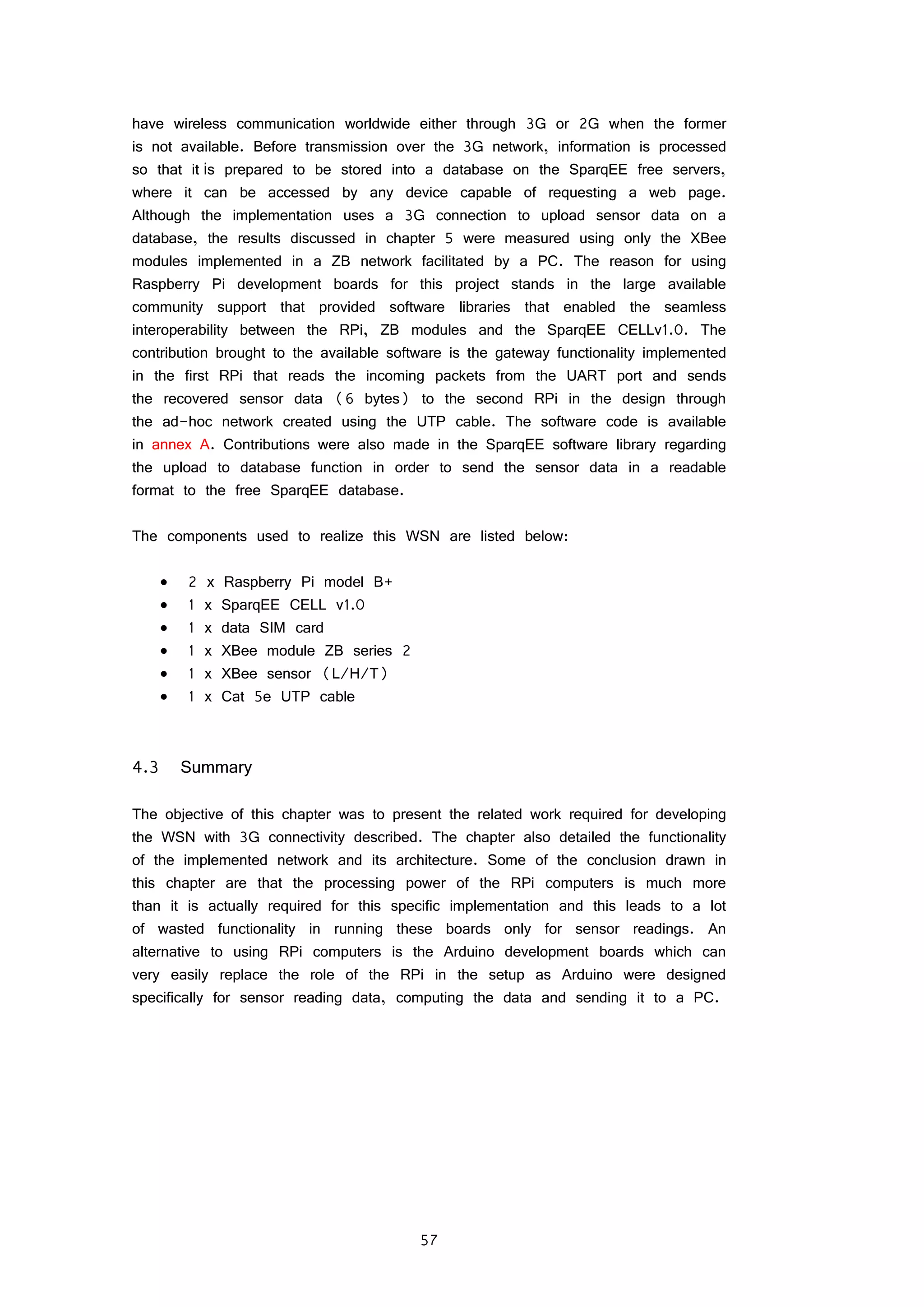

FIGURE 34 X-CTU SESSION CONFIGURATION 61

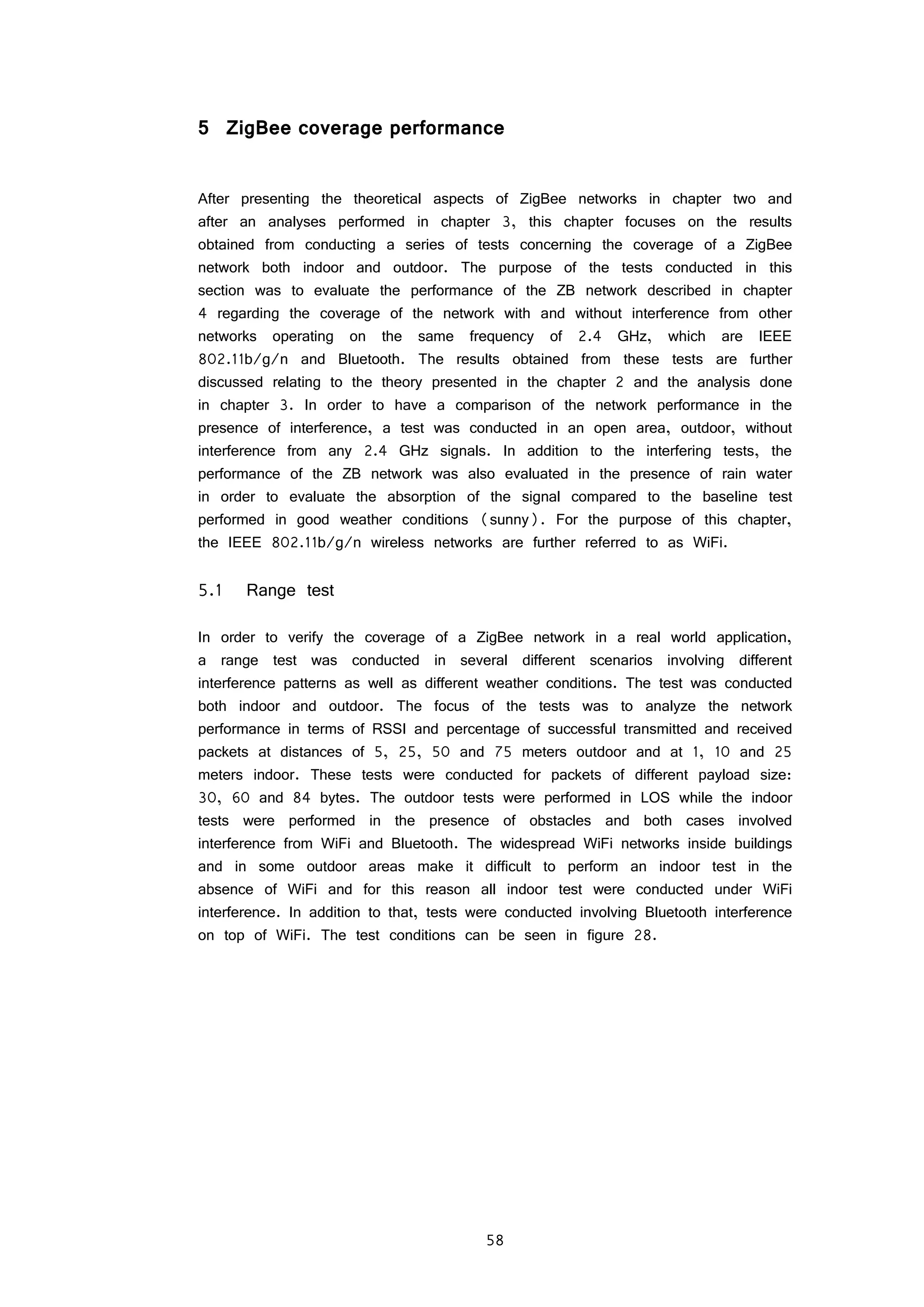

FIGURE 35 XCTU CHART WITH RSSI AND PDR 61

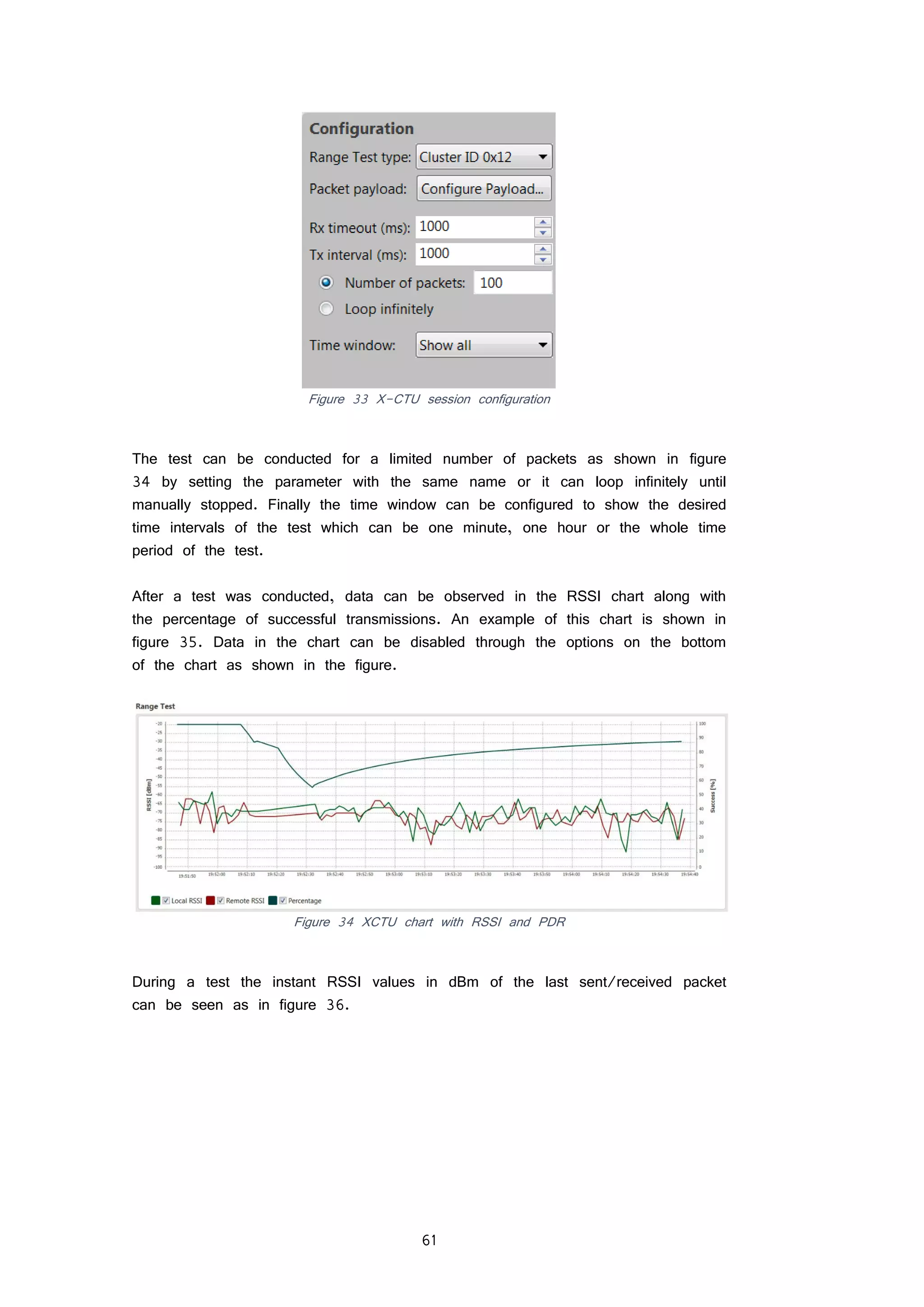

FIGURE 36 XCTU INSTANT RSSI VALUES 62

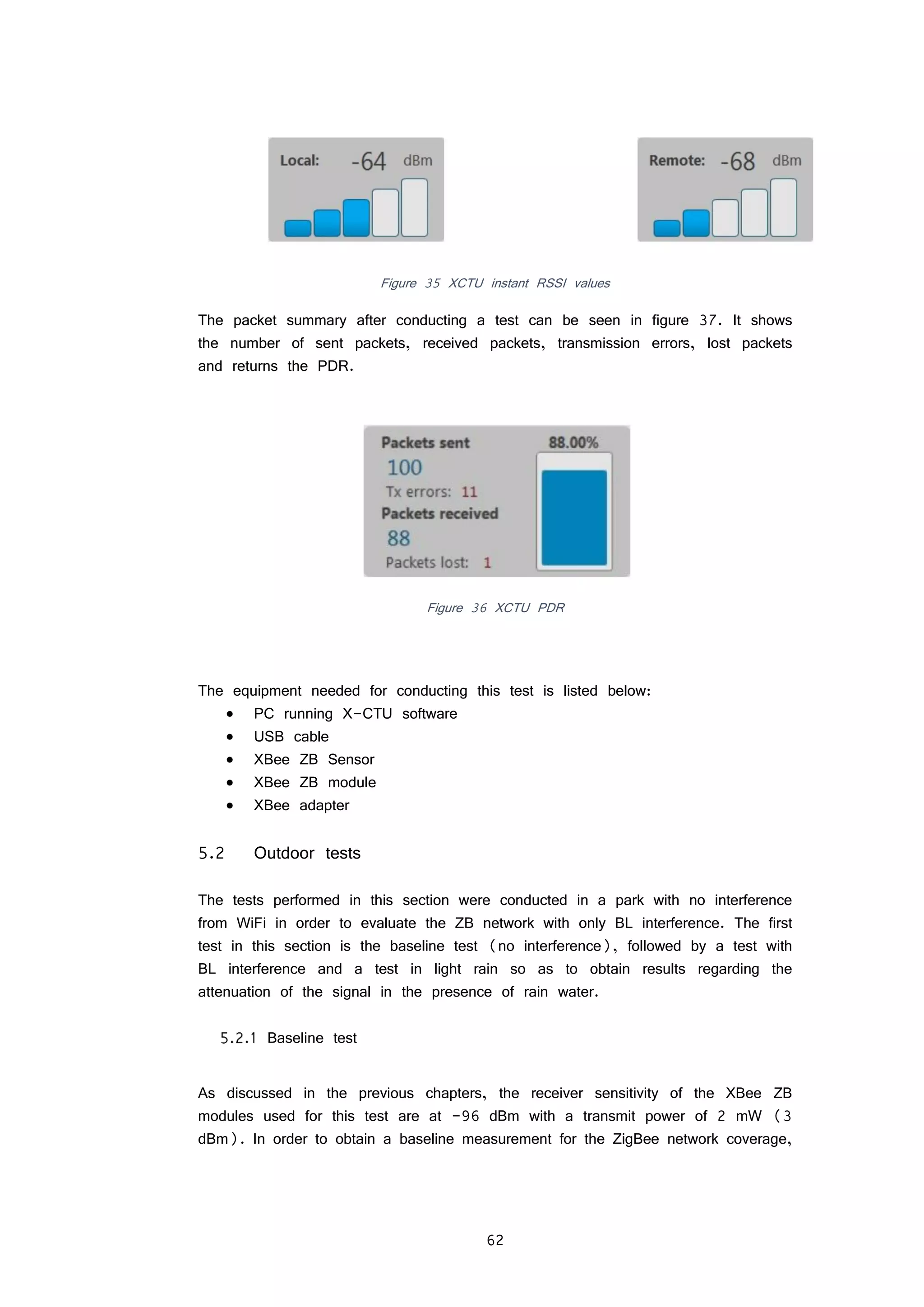

FIGURE 37 XCTU PDR 62

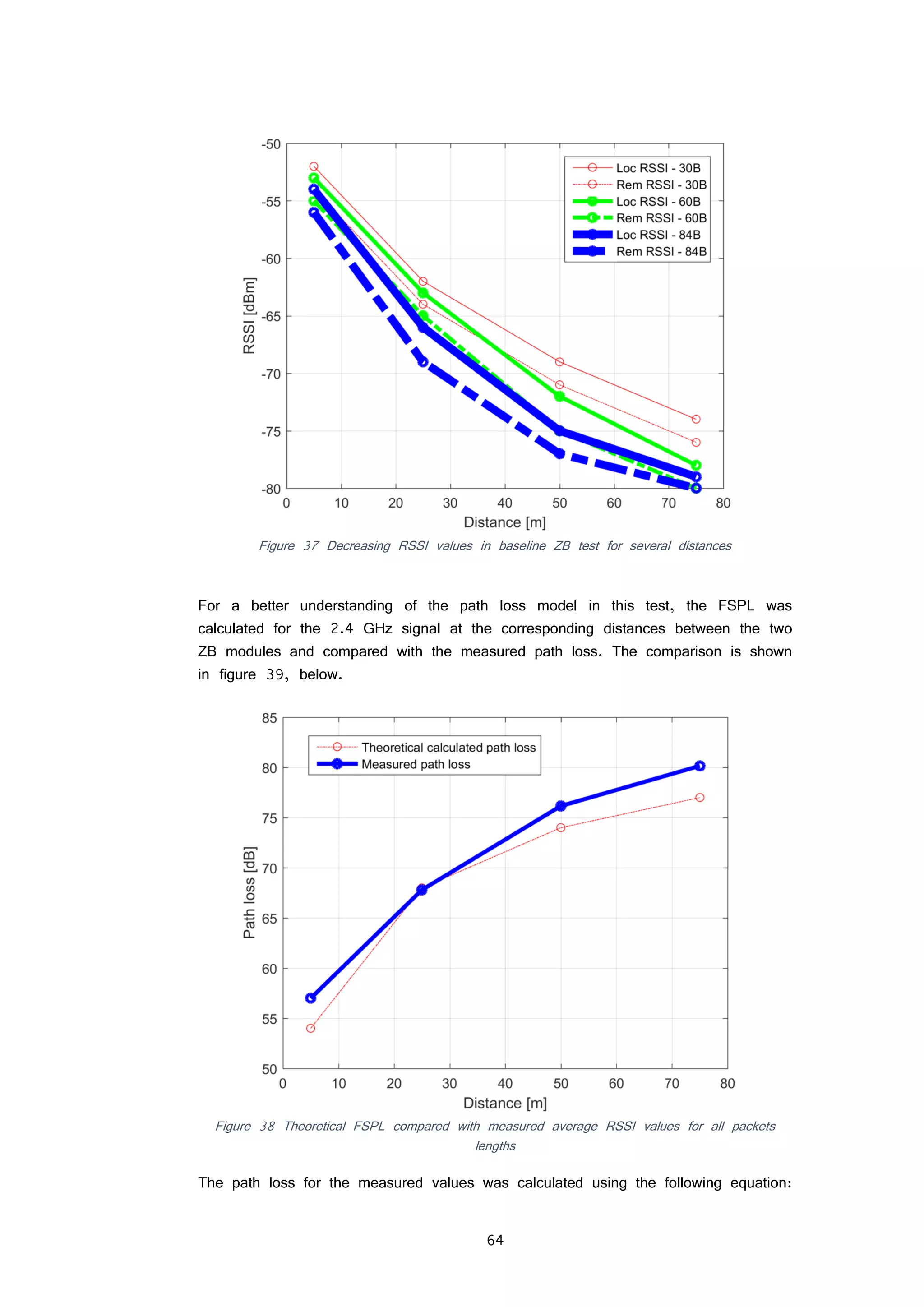

FIGURE 38 DECREASING RSSI VALUES IN BASELINE ZB TEST FOR SEVERAL DISTANCES 64

FIGURE 39 THEORETICAL FSPL COMPARED WITH MEASURED AVERAGE RSSI VALUES FOR ALL PACKETS LENGTHS

64

FIGURE 40 DECREASING RSSI VALUES IN BL INTERFERENCE TEST FOR SEVERAL DISTANCES 66

FIGURE 41 AVERAGE RSSI FOR BASELINE TEST COMPARED WITH BL INTERFERENCE 67

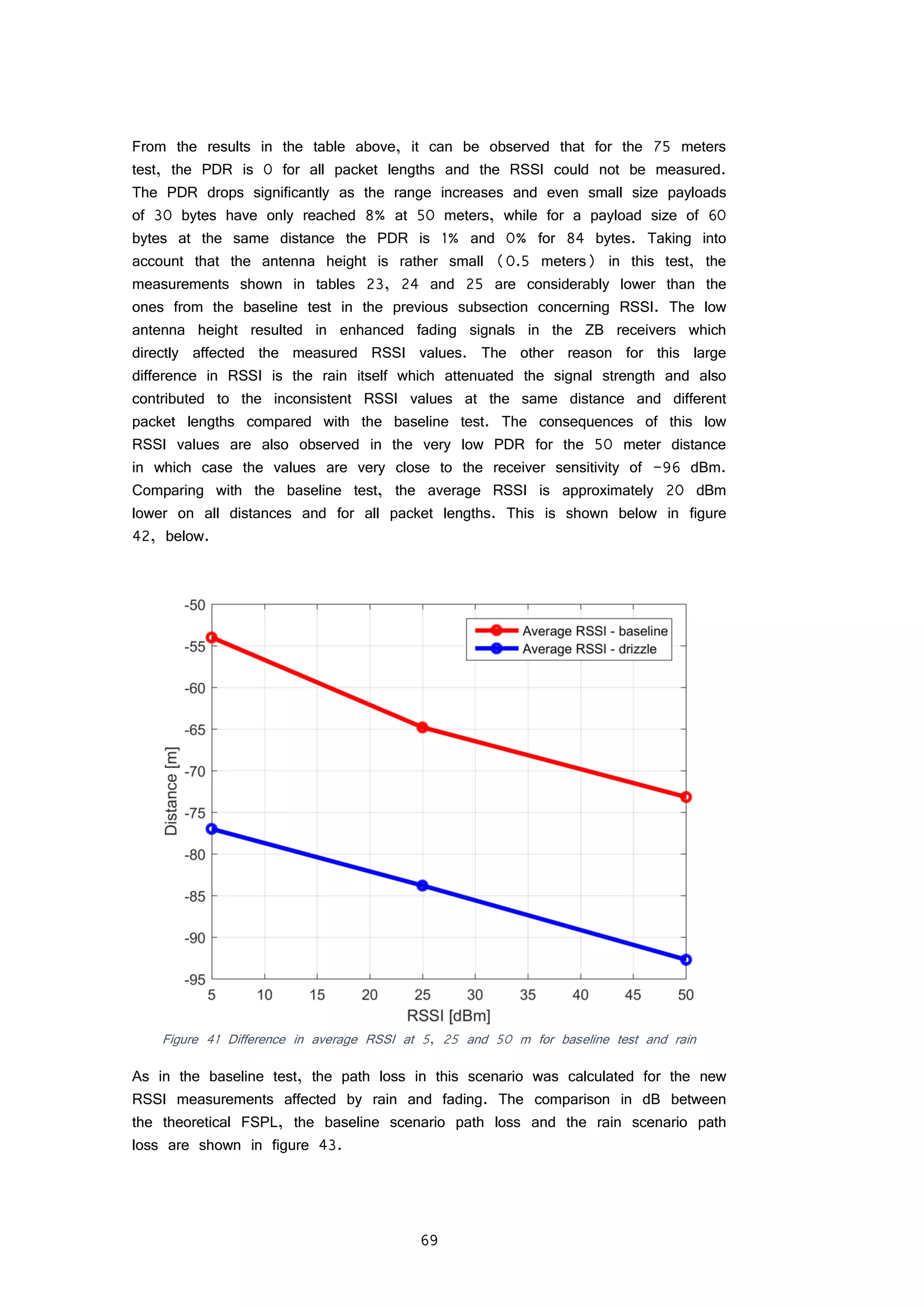

FIGURE 42 DIFFERENCE IN AVERAGE RSSI AT 5, 25 AND 50 M FOR BASELINE TEST AND RAIN 69

FIGURE 43 COMPARISON BETWEEN THEORETICAL FSPL, BASELINE PATH LOSS AND FADING PATH LOSS DURING

RAIN 70

FIGURE 44 COMPARISON BETWEEN THEORETICAL FSPL, BASELINE PATH LOSS, FADING PATH LOSS WITH AND

WITHOUT RAIN 71

FIGURE 45 RSSI MEASURED VALUES FOR INDOOR TEST WITH IDLE WIFI NETWORK INTERFERENCE 74](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e3e6b75-cfe2-4464-9902-e6012d3f991e-160126111244/75/Sensing-and-controlling-the-environment-using-mobile-network-based-Raspberry-Pis_final-7-2048.jpg)

![1 Introduction

Ever since the development of long distance communication, the focus was on

how to send more information in an efficient way and how to do it faster, cheaper

and more reliable. The first mediums of transmitting information were through cables

and the electric telegraph played an important role in exchanging information in

the industrial era. The arrival of radio technology represented a big step in the

evolution of wireless communication and the efficiency of mobile networks today is

an example of the exponential growth of this technology throughout the 20th

century

and the beginning of the 21st

. Initially, the focus of radio communication was on

transmitting voice messages in the form of analogue signals in the first generation

of mobile networks, but with the development of digital communication, the 2nd

generation allowed the transmission of data. This represented another big step in

the information era where data exchange has been prioritized over voice

communication for the purpose of reliably transmitting high volumes of data in a

short amount of time. The 4th

generation of mobile networks are an example of

high speed data transmission with data rates of up to 300 Mbps. The success

of mobile networks and the availability of an internet connection in most of the

countries around the world has led to the need of connecting more internet capable

devices that could provide valuable information without the need for human

interaction. This new concept of internet connectivity was called the Internet of

Things (IoT).

1.1 Internet of Things

The term “Internet of Things” was coined by Kevin Ashton in 1999. It refers to

the intercommunication of devices within a network and across networks without

the need for human interaction. This kind of network can have a big impact in

many sectors like health care, automotive, transportation and home automation and

it represents a big step in providing a low cost solution to a better quality of life.

Although the focus is on developing wireless technologies that can support such a

large number of devices, several barriers have the potential to slow the development

of the IoT. The three largest are the deployment of IPv6, power for sensors, and

agreement on standards. [36].

Key requirements that a technology must meet in order to sustain the billions of

devices that will be connected in the IoT network are as follows:

Highly scalable design

Very low power consumption of end devices

Large coverage and increased signal penetration](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e3e6b75-cfe2-4464-9902-e6012d3f991e-160126111244/75/Sensing-and-controlling-the-environment-using-mobile-network-based-Raspberry-Pis_final-9-2048.jpg)

![2

The requirement of IoT devices to communicate without the need of human

interaction has led to the development of a new type of machine communication

which is explained in the next subsection.

1.2 M2M communication

Machine to Machine (M2M) communication is one of the main facilitators of IoT

networks. In order to have an efficient and cost effective network, it is imperative

that these devices can communicate between themselves without any human

interaction. Current mobile technologies are not designed to integrate such devices

which require very low power consumption in order to provide functionality for an

extensive period of time (up to 10 years). A few technologies are being developed

today that focus on providing a low cost solution and very scalable design in

order to support the high data volume generated by these devices.

1.3 Motivation

The motivation to proceed with developing this project was born out of the curiosity

to know more about the role of sensor networks and the functionality of the

protocols that facilitate the transfer of low data rates in the IoT.

Objective

The objective of the project entitled “Sensing and controlling the environment using

mobile network based Raspberry Pis” is to provide a series of results based on

experiments took after the implementation process. These results and discussions

are meant to give the reader an overview about the capabilities of the tested

network in a scenario meant to address the IoT. In addition to these results, other

competitive technologies are analyzed and an assessment on the performance of

these technologies is compared in order to determine the best solutions for providing

connectivity to billions of devices in the IoT network.

Scope

The scope of this project is to evaluate the performance of a ZigBee network

regarding coverage and associated PDR (Packet Delivery Ratio) in different

environments.

Justification

The reason for researching this area of wireless networks stands in the fact that

there is a need for providing solutions to the IoT. It is estimated that by 2020

there will be more than 20 billion devices connected in the IoT network [36].

The latest technological advances in wireless technology as well as improvements

in the overall power consumption of such a system have been the missing key

elements in deploying low rate, low power wide area networks on a global scale.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e3e6b75-cfe2-4464-9902-e6012d3f991e-160126111244/75/Sensing-and-controlling-the-environment-using-mobile-network-based-Raspberry-Pis_final-10-2048.jpg)

![4

2 Wireless communication networks

In a general sense, networks have existed long before the introduction of the first

computer network. A group of people with common interests could be also called

a network of people or anything that is connected to something and/or dependent

on something could basically be a network. In the current report, the networks

that are of interest are wireless communication networks. This chapter’s focus is

on presenting the theoretical aspects relevant to understanding the project and its

results.

Sensor networks, as its name suggests, are networks in which end points are

sensors. These are usually deployed in scenarios where there is a constant need

to monitor certain processes in a system. The development of IoT devices has

made sensor networks to be deployed on a much larger scale. These networks

can now be regularly found inside a home, throughout a city or on a farm.

Wireless networks work in a similar way with mobile networks, but they generally

operate on unlicensed frequency bands and are used for data communication. The

most common standard in use today is the IEEE 802.11 (WiFi). Wireless networks

today represent a viable solution for offloading the huge amounts of traffic that

pass through the mobile networks. It is estimated that by 2019, most of the VoIP

data will be transferred over wireless networks [36]. Driven by the huge market

represented by the rapid growing IoT devices, standardization efforts are increasing

and many proprietary solutions for wireless networks based on M2M devices are

emerging. Low Power Wide Area (LPWA) networks will play a major role in

providing a backup solution for the billions of M2M devices.

Wireless communication networks have been a part of everyday life for a few

decades. Like most technological advances, in the beginning it was a very small

portion of the population who could afford a device capable of wireless

communication (e.g. mobile phone). Nowadays a mobile phone has become a

necessity in most places around the world. Cellular networks have facilitated mobile

communication to a global scale for a long time and continue to improve

exponentially in order to supply the current demand of quality services worldwide.

Mobile networks support both voice and data communication in contrast with only

data services in general wireless networks. Also in this section, the impact on

mobile data traffic of wearable and M2M devices is explored.

2.1 Sensor networks

The following sections regarding sensor networks and wireless networks are meant

to provide the reader with relevant information and theoretical aspects to the scope

of this project. In the first part, the reader is introduced to sensor networks and](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e3e6b75-cfe2-4464-9902-e6012d3f991e-160126111244/75/Sensing-and-controlling-the-environment-using-mobile-network-based-Raspberry-Pis_final-12-2048.jpg)

![5

the connection with IoT devices, while the second part is dedicated to wireless

networks and specifically wireless sensor networks.

Sensor networks have shaped the way we perceive and influence the environment

to a certain degree of detail, offering a wide range of services and information.

Initially these types of networks were not standardized, but with the emerging IoT

and the expansion of sensor networks to health care, automotive, home automation,

security and many more sectors, the need for a global set of standards is growing.

As discussed above, wide coverage M2M devices are being deployed on mobile

networks, but solutions for offloading mobile data traffic are needed and wireless

networks optimized for low rate and low power provide a good solution.

Figure 1 Sensor node architecture

Sensors are much like the human senses and they respond to a physical change

(like temperature, light, movement) in the environment they monitor. This response

produces inside the sensor an electrical signal which is processed and sent through

a wired or wireless connection to the unit that is responsible of further conversion

and processing. Sensors were developed as a way to better understand the

surrounding environment. Nowadays we are surrounded by sensors and they can

be found in mobile phones, cars, houses, bikes, in most electrical devices and

more. In the figure below, the architecture of a sensor node, and a basic idea

about how the components interact, is represented.

Recent evolution in technology and the limitation of the current power grid has led

to the development of smart-grid technologies. This transition to a digital network

presents many advantages like two-way communication, self-monitoring capabilities

and a network topology with distributed generation unlike the existing one with

radial layout and centralized generating capacity. The sensor market is facing new

challenges and benefits from new opportunities with the development of such a

grid with its goals being to increase efficiency, reliability and security [6]. Real-

time sensing and processing of information is very costly in power requirements

and it’s an unfeasible solution for sensor networks containing a large number of

end devices. In order to achieve very low power consumption, such a network

must use elements and technologies capable of providing an efficient, long term

solution to this issue. Over the past decades, sensors have become much smaller,

energy efficient and less expensive, but even though the cost of the sensor has](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e3e6b75-cfe2-4464-9902-e6012d3f991e-160126111244/75/Sensing-and-controlling-the-environment-using-mobile-network-based-Raspberry-Pis_final-13-2048.jpg)

![6

been greatly diminished, the cost to install them is way too high. In industrial

process automation the usual price for installing a wired sensor can be up to

$10,000 [7]. Because of this high cost, most sensors only transmit data to a

local controller in which case we cannot have an overall knowledge of a network

involving thousands of sensors. This led to the development of Wireless Sensor

Networks (WSN).

Figure 2 Sensor network architecture/star topology

This introduction to sensor networks was meant to provide the reader information

concerning the need that drove the development and rapid expansion of wireless

sensor networks and supporting protocols.

2.2 Wireless networks

This section is dedicated to understanding some of the wireless communication

technologies that facilitate the development of wide area WSNs and the impact

that global standardization of 4G/LTE for M2M devices has upon standards like

ZigBee and Bluetooth-LE and other proprietary LPWAN solutions like Sigfox and

Weightless.

The development of ALOHAnet in 1971 at the University of Hawaii, the first

wireless packet data network was an important step in further researching wireless

communication systems including 2G, 3G and WiFi (IEEE 802.11). The

development of smart devices capable of internet connectivity has led to an increase

in research done on possible solutions that fulfill the requirements of security,

scalability and performance of the IoT. Having this in mind, more traffic will be

offloaded from cellular networks to WiFi by 2016 [36].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e3e6b75-cfe2-4464-9902-e6012d3f991e-160126111244/75/Sensing-and-controlling-the-environment-using-mobile-network-based-Raspberry-Pis_final-14-2048.jpg)

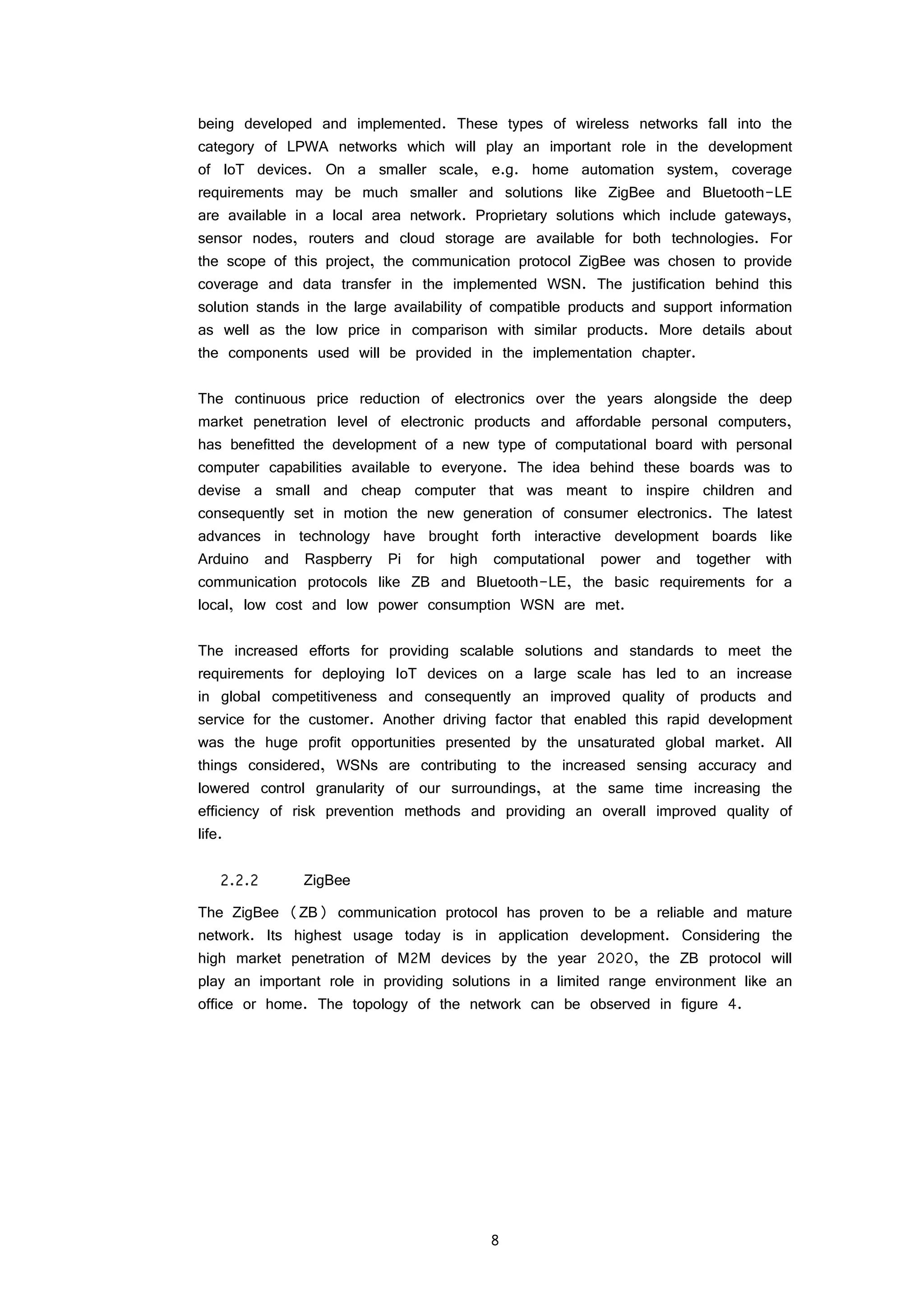

![10

up to 99% of the time and the tasks needed to send and receive information use

a small part of the devices’ energy, increasing battery life to years. Besides being

low cost and low power, ZB is flexible, allowing users to easily upgrade their

network in terms of security and efficiency. A few services that differentiate the

ZigBee protocol are:

Association and authentication

Routing protocol – an ad-hoc protocol designed for data routing and

forwarding: AODV [4]

Because the 2.4 GHz ISM band is also in use by microwave ovens, cordless

telephones, Bluetooth devices and the 802.11b/g standards, ZB may suffer from

heavy interference which is produced mostly because of the overlapping adjacent

frequency channels and heavy usage of this band, as only 3 non-overlapping

channels are offered out of the 16 on the 2.4 GHz band. To combat this

interference, the 802.15.4 protocol makes use of two techniques:

CSMA-CA (Carrier Sense Multiple Access-Collision Avoidance) – maximum

16 TS

GTS (Guaranteed Time Slots) – not suited for large number of devices

Another important aspect to consider when designing a WSN is reliability, so the

integrity of the information sent is verified through the use of ACK and NACK

messages between the transmitter and receiver. These kinds of packets are one

of the two most relevant types of packets that the ZigBee network transmits, the

others being data packets [4]. A few features of the ZigBee standard are presented

in table 1 [65].

Although the ZigBee protocol is using the same IEEE 802.15.4 RF protocol the

addressing and message delivery systems are different because of the added mesh

networking capabilities. There are two types of addressing: extended and network.

The extended address is a static 64-bit address which is guaranteed to be unique

and it is used to add robustness. The network address is a unique 16-bit address

which is assigned by the coordinator to a new node in the network. The extended

address is required in sending a message to the network while the network address

is not. Just like 802.15.4, broadcast and unicast messages are supported in

ZigBee.

Table 1 ZigBee network characteristics [65]

Attribute Characteristics ZigBee

Range

As designed 10-100 m

Special kit or outdoors Up to 400 m

Data

Rate

20-250 Kbps

Network

Network join time 30 ms

Sleeping slave changing to active 30 ms](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e3e6b75-cfe2-4464-9902-e6012d3f991e-160126111244/75/Sensing-and-controlling-the-environment-using-mobile-network-based-Raspberry-Pis_final-18-2048.jpg)

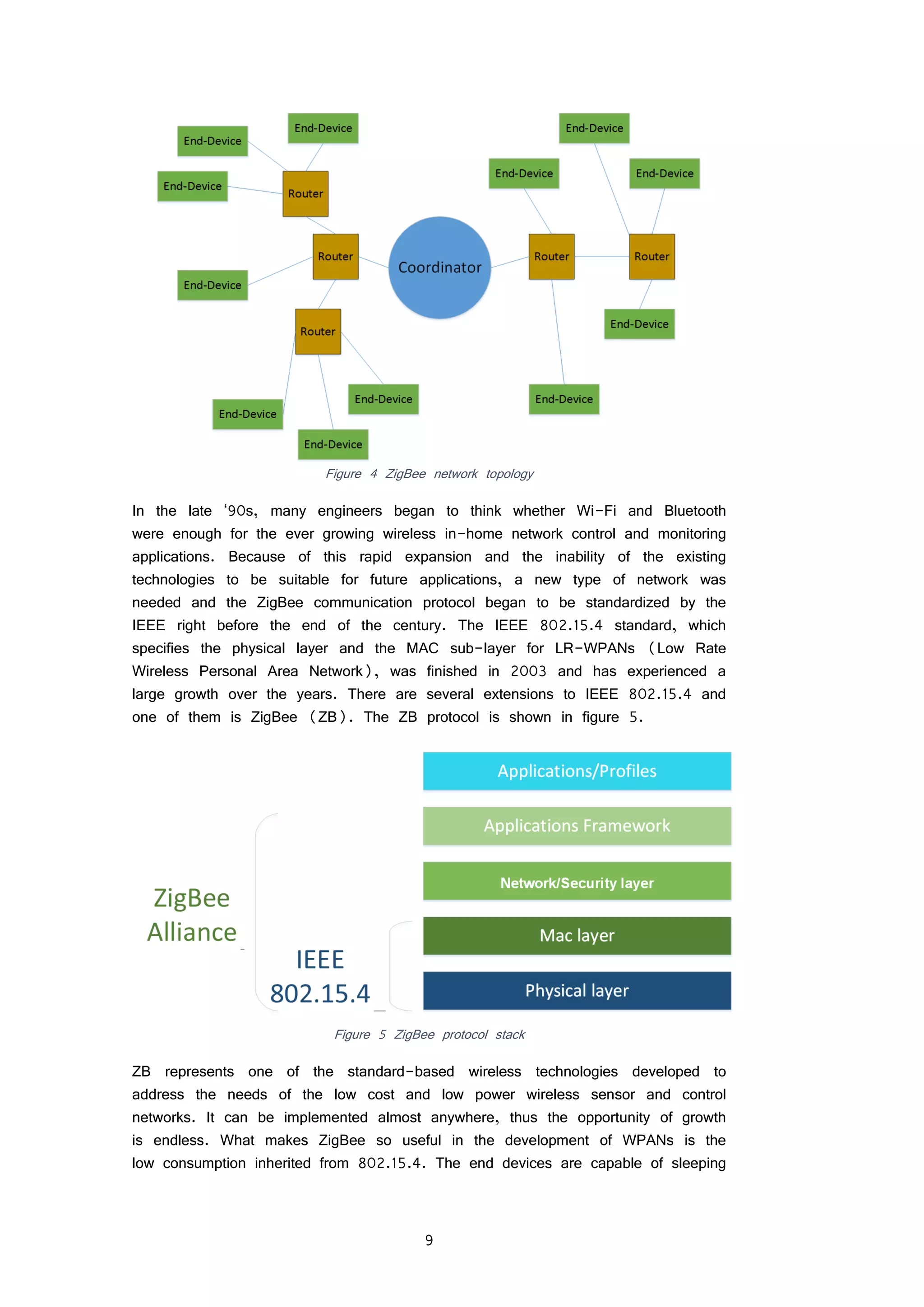

![12

earlier versions (Bluetooth 1.0) which had 1 Mbps, although most IoT devices

and applications require low data rates for the specific purpose of saving energy.

Although it was designed to replace cables, Bluetooth has evolved into a competing

technology for the emerging IoT with its ability of creating small radio LANs called

piconets or scatternets (a network of piconets). The latest update, Bluetooth-LE

(low energy) features ultra-low power consumption so devices can run on for

years on standard batteries as well as low costs of implementation and maintenance.

Unlike ZB which was defined on an existing protocol stack, the IEEE 802.15.4,

BLE was developed taking into account low power consumption on every level

(peak, average and idle mode) [41]. The BLE architecture can be seen in figure

6, below.

Figure 6 Bluetooth LE stack

It uses the ATT (Attribute protocol) to define the data transfer on a server-client

basis. Its low complexity directly influences the power consumption of the system.

The Generic Attribute Profile (GATT) is built on top of this protocol and it’s

responsible with providing a framework for the data transported and stored by the

ATT by defining two roles: server and client. ATT and GATT are crucial in a

BLE device since they are responsible for discovering services. The GATT

architecture provides accessible support for creating and implementing new profiles,

which facilitate the growth of embedded devices with compatible applications [41].

The low power consumption character of BLE in idle mode is given at the link

layer which is also responsible for the reliable transfer of information from point to

multipoint. Considering the re-designed PHY layer of BLE in contrast with previous

versions, two modes of operation were defined: single and dual mode. The

advantages of dual mode consist in compatibility between BLE devices and earlier

version devices, while single mode is the preferred solution in battery powered

accessories because of lower power consumption. At the link layer, power can be

conserved in a slave device by tuning the connSlaveLatency parameter which](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e3e6b75-cfe2-4464-9902-e6012d3f991e-160126111244/75/Sensing-and-controlling-the-environment-using-mobile-network-based-Raspberry-Pis_final-20-2048.jpg)

![13

represents the “number of consecutive connection events during which the slave

is not required to listen to the master” and can have integer values between 0

and 499. A connection event in this case is a non-overlapping time unit in a

physical channel after a connection between a master and a slave has been

established [41, 43].

One very important feature of the IoT is scalability considering the billions of

devices that will flood almost every environment during the next 5 to 10 years.

Bluetooth classic has the capability to create small LANs in order to exchange

various data like photos or videos, but the address space of 3 bits only allows

for maximum 8 devices in the same network. [42] Although this represents a

great feature for very small areas, it doesn’t provide a scalable solution for large

networks involving M2M devices with low power consumption. BLE instead has a

32-bit address space which means that, theoretically, the network size can be

the same as for IPv4, more than 4 billion. However, there are limitations to this

number given by the type of communication between master and slave and certain

parameters, like BER and connInterval. This parameter represents the “time between

the start of two consecutive connection events” [43]. The values that this parameter

can take are a multiple of 1.25 ms between 7.5 ms and 4 s.

Considering the evolution of Bluetooth, which started out as a wireless

communication technology to replace cables, it has taken great steps into providing

a reliable and cost effective solution for wireless communication systems on a

global scale. The small hardware dimensions as well as the power efficiency have

made this into a most wanted technology in most smart phones, laptops and many

other wireless capable devices powered by battery. The latest update, BLE, is

meant to extend its usage to IoT devices by providing ultra-low power consumption

in end devices and increased network size for scalability purposes. Although the

Bluetooth SIG has made great efforts to provide this solution, BLE is still facing

some problems that make it less appealing for IoT applications:

The operating frequency of BLE is 2.4 GHz in the ISM unlicensed spectrum.

The already high interference level at this frequency will only get worse

by introducing millions of new devices resulting in much lower reliability.

Although the PHY layer data rate is 1 Mbps, testing done in this [43]

article has shown that the maximum application layer throughput is 58.48

kbps due to implementation constraints and processing delays. This value

may be enough for some IoT applications, but it’s not a solution in case

of higher data transfer applications.

Unlike other technologies working in sub-GHz spectrum, the coverage of

BLE is limited and the 2.4 GHz band is not the most suited for wall

penetration (e.g. basement) or in rainy situations. Creating scatternets

may prove as a solution to extending coverage, although this creates high

network complexity.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e3e6b75-cfe2-4464-9902-e6012d3f991e-160126111244/75/Sensing-and-controlling-the-environment-using-mobile-network-based-Raspberry-Pis_final-21-2048.jpg)

![14

2.3 Cellular networks

This section is dedicated to assessing the possible solutions for the IoT provided

by cellular technologies. Currently deployed cellular technologies like 2G, 3G and

4G/LTE were not designed to handle billions of devices working on

Mobile networks continue to expand at an alarming rate and optimization techniques

are constantly used to provide a seamless experience for the users. Today, the

majority of mobile data traffic (~80%) is transferred indoors. This presents a big

challenge for network operators to provide solutions for the constant demand for

faster and better quality data. Standardization efforts from the 3GPP group are

also increasing and it is imperative to plan a few steps ahead considering the

fast expansion. As discussed earlier in the introduction, the impact of the Internet

of Things on the mobile data traffic is not something to ignore. Cisco predicts

that by 2020 more than 20 billion M2M devices (home automation, smart

metering, maintenance, healthcare, security, transport, automotive and many more)

will have internet connectivity comparing to 495 million in 2014 [36]. Although

only about 200 million will have mobile network connectivity according to a white

paper from Nokia [50], representing a 26% increase in CAGR.

Another category with high growth potential among internet connectable gadgets is

represented by wearable devices like smart watches, health monitors, navigation

systems and more. These devices can either connect directly on the network or

through a mobile device (via Wi-Fi or Bluetooth). It is estimated by Cisco that

by 2019 the wearable devices (e.g. smart watches, health care devices) will

reach approximately 578 million globally, having a CAGR of 40% [36]. In figure

7 a visual representation of CAGR increase between 2014 and 2019 is shown.

Figure 7 Global mobile data traffic, 2014-2019 [34]

In the following paragraphs, a few details about mobile networks history are

presented followed by a more detailed view on the relevant technologies for this

project.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e3e6b75-cfe2-4464-9902-e6012d3f991e-160126111244/75/Sensing-and-controlling-the-environment-using-mobile-network-based-Raspberry-Pis_final-22-2048.jpg)

![15

As opposed to traditional wired networks in which a connection between two users

is established through a physical link, mobile networks are characterized by the

use of wireless communication technologies to deploy services to users. The cellular

concept of mobile networks was defined first in 1947 [32], a radical idea at that

time when most of the research was about providing radio coverage on an area

as large as possible from one base station (BS). This was in contradiction with

the cellular concept which proposed limiting the signal from a BS to a specified

area in order to reuse the same frequencies in neighboring cells, which had their

own transceiver. Such a system permitted the subscription of many more users in

a region, but this only became feasible in the 1980s when the advances in

technology brought forth electronic switches, integrated circuits and handover

techniques [32, 18]. Another factor that impeded the earlier deployment of cellular

networks were the lack of standardization efforts.

The first generation of mobile networks was commercially deployed in the 1980s

and it was solely based on classic circuit switching (CS). This method involved

switching analogue signals in a switching center with the help of a matrix which

mapped all the possible source and destination paths. Communication was possible

both ways once a physical connection was established between the two end points

(hosts) [18, chapter 1].

Following this introduction, the following sections explore the different characteristics

of the relevant generations of mobile networks.

2G

The following subsection has the scope of introducing the reader to the most

important elements that make up the second generation network. GSM represents

the foundation for all future cellular networks.

2G (GSM) represents the second generation wireless telephone technology which

was a great improvement in 1991 since it introduced digital communication over

the traditional analogue and more efficient usage of spectrum. Being the first

commercially deployed wireless digital communication technology, GSM has been

implemented in most of the countries around the globe given its increased

accessibility over the years. This had a direct effect on the availability of the

system which led all further upgrades (GPRS, EDGE, UMTS, HSPA and LTE)

to provide compatibility with GSM in the absence of a better technology. Other

reasons were cost and time required to deploy a new infrastructure. In figure 8

the GSM network architecture is presented.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e3e6b75-cfe2-4464-9902-e6012d3f991e-160126111244/75/Sensing-and-controlling-the-environment-using-mobile-network-based-Raspberry-Pis_final-23-2048.jpg)

![16

Figure 8 GSM network architecture

Some of the most important functions performed by GSM’s network elements are:

channel allocation/release, handover management, timing advance

The GSM standard only allows 14.4 kbps over the traffic channel (user data

channel) which can be used to send digitized voice signal or circuit-switched data

services. GSM only allowed a circuit switched connection over the network and

thus billing for data was done per minute connected. [18] Despite the voice

oriented design of 2G, several upgrades have been added to the network to

facilitate the transfer of more data and faster over the same infrastructure. One

major update, that would eventually become the focus of future mobile networks,

was the introduction of data communication, namely the PS network. On GSM,

SMSs are sent through the signalling channels, but from GPRS onwards, the SMS

is treated as data and it is being conveyed on the traffic channel.

By the year 2000, mobile phone users were already experiencing the data friendly

GPRS (General Packet Radio Service). With this release, data services

experienced a large growth and data rates of up to 70 kbps were realistic. This

upgrade was possible due to the improved radio quality and dedicated TS for

data. The biggest differences in the new architecture were the addition of a packet

switched core network to deal with all the data traffic available and a PCU (Packet

Control Unit) to be installed on all BSC to provide a physical and logical interface

for data traffic. Unlike GSM, billing for data connection was done per traffic volume.

These architecture differences can be seen in figure 9. Alongside a packet control

unit, the PS network also contains a GGSN (Gateway GPRS Support Node)

which routes packets and interfaces with external networks and a SGSN (Serving

GPRS Support Node) which is responsible for registration, authentication, mobility

management and billing information. Soon after, in 2003, EDGE (or 2.75G) was

being deployed on GSM infrastructure and was introduced as the “high-speed”

version of GPRS. This release, almost as powerful as 3G, was capable of

delivering realistic data rates of up to 200 kbps by using a new modulation

format, new coding schemes and incremental redundancy.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e3e6b75-cfe2-4464-9902-e6012d3f991e-160126111244/75/Sensing-and-controlling-the-environment-using-mobile-network-based-Raspberry-Pis_final-24-2048.jpg)

![17

Figure 9 GPRS Architecture

The vast accessibility of GSM around the globe has ensured its long existence,

although a full transition to the PS network is desired because of the huge costs

of maintaining two networks at the same time. The solution for an only PS network

has been specified starting with release 7 from 3GPP [36]. Fallback to the CS

network is possible in case of PS network failure though the CS Fallback

procedures, also specified by 3GPP.

An analysis on the amount of users/mobile network performed by Cisco in 2014

shows that the majority of mobile devices, 62%, are using 2G for connectivity. It

is estimated that by 2017 GSM will no longer be the majority holder of mobile

connections, dropping down to only 38% and by 2019 to 22% [36]. An evaluation

of technology adoption for M2M devices in 2014 was performed by EMEA and

the results showed that 2G is still the preferred technology in automotive industry,

transportation, energy and security. The primary reason behind favoring 2G networks

for M2M devices is the price to embed 2G connectivity onto devices, followed by

worldwide availability of the network [37].

In the 2G section, a few important details were covered about the mobile network,

ending with a short evaluation on the impact of 2G in mobile networks today, as

well as the impact and relation with M2M devices.

3G

A few details about the involvement of 3G in the IoT are discussed in this section

and also the how it relates to the current project. The following part will be

dedicated to detailing a few characteristics of 3G networks and what were the

driving factors into developing this network.

The 3G network represents a transition network from a few points of view. On

one side, it’s meant to provide a smooth evolution to an only PS network. As

discussed before, maintaining 2 networks (CS and PS) at the same time can

be very costly and inefficient. From another point of view, the transition of M2M](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e3e6b75-cfe2-4464-9902-e6012d3f991e-160126111244/75/Sensing-and-controlling-the-environment-using-mobile-network-based-Raspberry-Pis_final-25-2048.jpg)

![18

devices from 2G to LTE networks is also happening gradually through the 3G. By

2016, a report from Sierra Wireless predicts that most of the technological sectors

(including automotive, transportation, energy and security) will provide support for

3G connectivity. For the purpose of this project, this is the main network responsible

with internet connectivity.

The 3G network today represents a transition network between the old circuit

switched and the future only packet switched networks. The 2nd

generation mobile

networks limitations, like “the timeslot nature of a 200 kHz narrowband transmission

channel and long transmission delays” [18, page 116], did not permit a further

upgrade and so, by the end of the millennia, the standardization of UMTS (3G)

was finished and it presented capabilities far beyond that of the previous generation.

The most important requirements taken into consideration for this new system were

the increase in bandwidth, flexibility and quality (QoS).

Figure 10 UMTS network architecture

Considering the architecture of the 3G network in figure 10, besides the same

core network a few major changes can be observed in the radio access network.

For example the BS is now called Node-B but maintains the same functions as

a BS. New interfaces are specified (Iu, Iur, Iub and Uu) for communication

between different network elements. In the Radio Network Subsystem (RNC) the

BSC is replaced with Radio Network Controller (RNC) which control the Node

Bs.

Although this is a new generation of mobile networks, UMTS was not built from

zero and initially reuses a lot of GSM and GPRS with the exception of the radio

access network (UTRAN), which was completely new. The new radio interface

uses 5 MHz frequency channels with bit rates that reach up to 384 kbps with

the new WCDMA multiplexing scheme, which supports more users compared to

TDMA. In this new coding scheme, everyone is transmitting at the same frequency

and at the same time, resulting in a high spectral efficiency. Even though this is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e3e6b75-cfe2-4464-9902-e6012d3f991e-160126111244/75/Sensing-and-controlling-the-environment-using-mobile-network-based-Raspberry-Pis_final-26-2048.jpg)

![19

very efficient usage of spectrum (frequency reuse factor = 1), the overall capacity

and coverage of the network decreases with the increase in connected users to

the same cell [18, chapter 3]. EDGE Evolution was developed after the release

of 3G and it was designed to improve coverage for HSPA (High Speed Packet

Access). Maximum throughout achieved can be up to 1.3 Mbps in downlink [22].

As discussed previously in the 2G section, currently 62% of devices use GSM for

connectivity, but in the near future this will drop to 38% in favour of 3G initially

with an emphasis on 4G later on. By 2017, 45% of devices will function on 3G,

although the growth will rapidly stabilize and even fall by 2019 to 44% [36].

LTE/4G

This sub-section presents on overview of the LTE (Long Term Evolution) standard

as well as 4G together with a few details about the implications and benefits of

M2M devices in relation to LTE-M.

The advances in cellular networks from lower-generation networks (2G) to higher-

generation networks (3G, 3.5G and 4G/LTE) are partly due to the increasing

computing capabilities of end devices which demand higher BW (bandwidth).

Therefore, the adoption of 4G and its overall deployment is rapidly increasing. The

fastest adoption rate is observed in the USA with 19%, while Europe is only at

2% in 2014 [37]. Currently only 6% of devices are using 4G, but by 2019 Cisco

estimates an increase to 26%. At the same time, the amount of data generated

by 4G networks by 2019 will represent 60% of the total [36].

The evolution towards an exclusive PS network is realized through a series of

supporting technologies developed around the 4G standard. Solutions like IMS VoIP

(Internet Media Services Voice over IP) and SMS over IP are fully specified by

3GPP in release 7 (3rd

Generation Partnership Project) in the LTE standard

[34]. Initially voice information was delivered through the CS network which is

presents in both 2G and 3G. 4G was designed to be the mobile network of the

future and along with it the transition from CS networks to PS network is complete,

although as discussed above, fall back solutions to former CS services are

available. Through a series of new network elements, the 4th

generation network

manages to maintain only one network. The overall simplicity of the packet-oriented

of network is due to a few changes in how it is functioning and handling data.

For a start, the new eNode-B (evolved Node-B) has completely took over the

radio related functionalities of the former RNC, like resource allocation, scheduling,

re-transmission and mobility management. The PS and CS networks were combined

into EPC (Evolved Packet Core) which efficiently handles incoming data by

separating user and control planes. The control is now handled by the MME

(Mobility Management Entity), which is responsible with authentication, security,

mobility management as well as subscription. The SGW (Serving Gateway) handles

all user switching and data forwarding as well as access to external networks

through the PDN-GW (Packet Data Network Gateway) [18, chapter 4].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e3e6b75-cfe2-4464-9902-e6012d3f991e-160126111244/75/Sensing-and-controlling-the-environment-using-mobile-network-based-Raspberry-Pis_final-27-2048.jpg)

![20

Figure 11 LTE network architecture

An important aspect of the 4th

generation mobile network that is directly influencing

the IoT is BW allocation. As discussed above, more than 3 billion IoT devices

are expected to have data connectivity and out of those, Cisco predicts that only

13% will have connection through 4G in 2019 [36]. On top of this, the wearable

devices market is also growing considerably and will present an impact on the

amount of mobile traffic. The justification of adopting M2M devices on the 4G

network is given by the significant revenue opportunities for mobile operators as

well as the general desire to migrate 2G traffic to 4G. M2M devices designed for

4G should also be produces at the lowest cost in order to be cost effective with

GSM/GPRS devices [39].

Starting with release 12 [39], 3GPP has begun specifying a new category of

M2M devices that would be feasible and compatible with the existing infrastructure.

These devices are specified under the LTE-MTC (LTE-Machine Type

Communication), details of which shown in the sub-section below.

The cellular networks presented above represent the existing technologies that were

developed for the specific purpose of standardized global mobile communication.

The second generation 2G network, the first globally deployed cellular network

which provided a leap forward from analogue transmission, together with the

following upgrades 3G and 4G have focused primarily on providing efficient and

scalable solutions for voice and data communication. Considering the requirements

of IoT devices and networks, these existing solutions are not designed to integrate

billions of devices with completely different types of transmissions and capabilities.

The remaining sections of this chapter are focused on understanding the implications

that IoT brings and what is required in the development of such a communication

system.

2.3.3.1. LTE-M

The mobile internet trend has been to constantly increase capacity for high BW

consumption applications and broadband services leading to very high data rates

in LTE and 4G networks. The M2M devices are designed for low BW consumption](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e3e6b75-cfe2-4464-9902-e6012d3f991e-160126111244/75/Sensing-and-controlling-the-environment-using-mobile-network-based-Raspberry-Pis_final-28-2048.jpg)

![21

and so, wide area M2M connectivity requires new standardization efforts to the

current technologies. Some of the key requirements of M2M devices for LTE are

[38, 39]:

Wide service spectrum – diversity in types of services, availability and

BW.

Low cost connected devices

Long battery life

Coverage enhancements – placement of devices in low or no signal

areas

Support data rates at least equivalent to EGPRS

Ensure good radio frequency coexistence with legacy LTE radio interface

and networks

Beside the requirements presented above, considerations for addressing (IPv6 is

recommended), signaling and roaming need to be investigated. The existing LTE

network architecture is sufficient for the time being, but the fast growing number

of M2M devices and the rapid adoption pace towards 4G requires new network

elements to handle the new features and the many different types of services

[38]. Design consideration of M2M devices following a low cost scenario include:

1 Rx antenna

Downlink and uplink maximum TBS (Transport Block Size) size of

1000 bits – means that peak data rates are reduced to 1 Mbps

in downlink/uplink (DL/UL) [38]

Reduced downlink channel BW of 1.4 MHz for data channel in

baseband while uplink channel BW and downlink and uplink RF

remains the same as for normal LTE UE [39]

Optional: half duplex FDD devices will be supported for additional

cost savings

Following de design considerations mentioned above, a few potential techniques for

improving LTE M2M device coverage on the physical channel are shown in table

2.

Table 2 Potential coverage enhancements techniques on physical channels [62]

Technique PUCCH PRACH PUSCH EPDCCH PBCH PDSCH

PSS/

SSS

Repetition/subframe

bundling

X X X X X X

PSD Boosting X X X X X X X

Relaxed Requirement X X

Overhead reduction X

HARQ retransmission X X

Multi-subframe channel

estimation

X X X X X](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e3e6b75-cfe2-4464-9902-e6012d3f991e-160126111244/75/Sensing-and-controlling-the-environment-using-mobile-network-based-Raspberry-Pis_final-29-2048.jpg)

![22

Multiple decoding

attempts

X

Increased reference

signal density

X X

Taking into consideration the requirements mentioned above, the LTE-M standard

is developed to support long battery life of 10+ years for end-devices in order to

follow the most cost effective plan. In release 12 [39] a power saving mode

(PSM) is introduced which significantly improves battery life of end devices. This

sleeping mechanism allows the device to stay registered with the network in order

to reduce signaling and consequently reduce power consumption. A similar sleeping

mode was discussed in the ZigBee section, although in contrast with the ZB

sleeping cycle, a M2M device remains in PSM until it is queued to perform a

network procedure. In release 13 from 3GPP, this feature is improved even further

e.g. increasing DRX (Discontinuous Reception) cycle form 2.56 seconds to 2

minutes results in a battery-life increase from 13 months to 111 months. In table

3 are shown different features available with the current and future 3GPP releases.

Table 3 LTE features for M2M services [62]

LTE Release Feature

Rel-11 (2012)

UE power preference indication

RAN overload control

Rel-12 (2014)

Low-cost UE category (Cat-0)

Power saving mode for UE

UE assistance information for eNB parameter tuning.

Rel-13 (2016)

Low-cost UE category

Coverage enhancement

Power saving enhancement

Although LTE-M has been specified by 3GPP, the high costs of deploying end

devices that integrate into the LTE network is not feasible at the moment. As

discussed in the section above, only 13% of total M2M connections worldwide will

be supported by LTE-M [36] by 2020, while more than 50% will be supported

by 2G and 3G.

2.4 Low Power Wide Area Networks

The numerous standardization efforts today that are focused on IoT devices and

related communication protocols are looking to provide solutions for local or regional

area networks, solutions which can effectively offload the M2M traffic from the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e3e6b75-cfe2-4464-9902-e6012d3f991e-160126111244/75/Sensing-and-controlling-the-environment-using-mobile-network-based-Raspberry-Pis_final-30-2048.jpg)

![23

global 4G network. In a white paper from Cisco [36], the migration of wide area

M2M devices from 2G to 3G and ultimately to 4G is taking a fast pace and by

2019, 4G M2M devices will reach 13% of the total M2M connections, while 3G

will hold 35% and 2G only 23%. By that time, LPWA networks will also play an

important role in transporting the large amount of M2M traffic, which will represent

29% of the total connections.

Figure 12 LPWA network deployment scenarios

Some of the requirements for LPWA networks include:

Low throughput

Low power

Wide area coverage

Scalable solution

Low cost

The sub-GHz spectrum provides high signal propagation while maintaining a low

cost for end device equipment. This enables radio waves to provide connectivity

in basements or behind thick concrete walls. The wide area coverage of these

low power networks is a driving factor for large scale deployment in all types of

environments as shown in figure 12. The cloud based controller is responsible with

keeping track of all network elements and traffic handling. Considering this use

case application and how data will be managed in the IoT, a possible architecture

is considered in the next subsection.

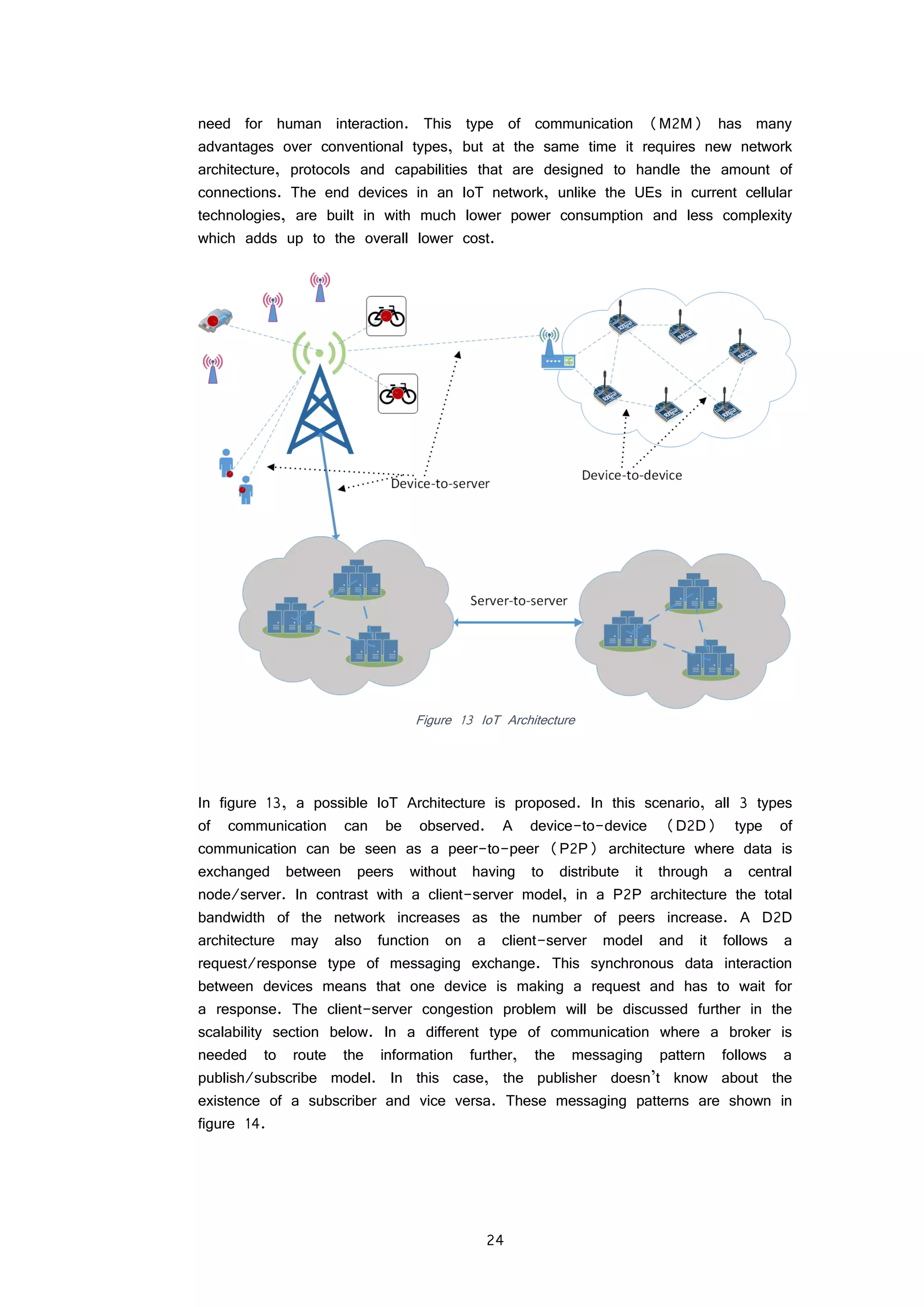

IoT architecture

Following the big success of cellular networks in terms of scalability, coverage and

low complexity, the technologies that are meant to support the IoT are being

developed having the same topology in mind. The major difference in an IoT

network is that devices are meant to communicate between themselves without the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e3e6b75-cfe2-4464-9902-e6012d3f991e-160126111244/75/Sensing-and-controlling-the-environment-using-mobile-network-based-Raspberry-Pis_final-31-2048.jpg)

![26

higher propagation (behind thick walls, basements, sewers) as opposed to current

cellular technologies which operate on higher frequencies, unsuitable for these tasks

in these environments.

The Weightless open standards which are designed as a cellular low power wide

area network operate on sub-GHz license free spectrum. Competing technologies

like ZigBee, Bluetooth-LE and Wi-Fi which also operate on unlicensed spectrum

but on higher frequencies (2.4 GHz) offer cheap endpoints as well, but the

coverage of these solutions is much smaller and can only account for short-range

applications. The coverage required in sectors like automotive, healthcare and asset

tracking is much larger than these technologies can provide. Depending on the

application and the environment, Weightless has defined 3 standards to provide

support in all the sectors that will benefit from the IoT. The table below shows

the differences between these standards.

Table 4 Weightless open standards [44]

Weightless-N Weightless-P Weightless-W

Directionality 1-way 2-way 2-way

Feature set Simple Full Extensive

Range 5km+ 2km+ 5km+

Battery life 10 years 3-8 years 3-5 years

Terminal cost Very low Low Low-medium

Network cost Very low Medium Medium

The high propagation characteristic of Weightless-N is achieved by operating on

sub-GHz spectrum, using ultra narrow band (UNB) and software defined radio

technology. This technology offers the best tradeoff between range and transmission

time. Transmission on narrow frequency bands is realized by digitally modulating

the signal with a differential binary phase shift keying (DBPSK) scheme and

interference mitigation is accomplished by using a frequency hopping algorithm. The

UNB technology behind this standard is provided by Nwave, a leading provider of

network solutions for the IoT, both hardware and software. The problem of multiple

Weightless networks operated by different companies in the same area is solved

by using a centralized database to determine in which network the terminal is

registered for decoding and routing purposes. At the same time the advanced de-

modulation techniques make it possible for Weightless to co-exist with other radio

technologies working within the ISM bands, thus avoiding collisions and capacity

problems [44]. Database querying is done by base stations. The star architecture

allows up to 1,000,000 nodes to connect to one base station [45]. The network

architecture for a Weightless based communication network is shown in figure 15,

below.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e3e6b75-cfe2-4464-9902-e6012d3f991e-160126111244/75/Sensing-and-controlling-the-environment-using-mobile-network-based-Raspberry-Pis_final-34-2048.jpg)

![27

Figure 15 Weightless network architecture

The Weightless-W standard was the first of these standards to be released and

its most important feature is the usage of TV white space spectrum. This unlicensed

white space represents the unused TV channels which account for approximately

150 MHz in most locations around the world [47]. This means that the TV

spectrum will be used by both licensed and unlicensed users which will unavoidably

create interference. In order to maximize the spectrum usage and avoid interfering

with TV channels, out-of-band emissions have to be minimized and depending on

application, modulation schemes like DBPSK, SCM (Single Carrier Modulation)

and 16-QAM are used. Other methods of interference mitigation used are frequency

hopping, scheduling and spreading [46, 47]. This technique also represents a key

factor in designing these networks because it is the only way to achieve long

range with low power at the cost of throughput. Spreading factors from 1 to 1024

can be used based on the Weightless specification. In contrast with Weightless-

N, designed for applications that require very low data rates with 1-way

communication, data rates for end devices operating on Weightless-W are between

1 kbps and up to 10 Mbps with variable packet size depending on application and

link budget [46]. Weightless-W provides very flexible packet sizes from 10 bytes

with no upper limit and a very low overhead size of less than 20% in packets

as small as 50 bytes [47].

An important factor to take into consideration about Weightless is that it’s an open

global standard, leaving the user a lot of room for customization and future

innovation at a much lower cost than a mobile network.

Sigfox

One of the major competitors to Weightless is Sigfox, a cellular network designed

to address the specific need of very low throughput applications that are part of

the IoT. Similar to mobile networks, Sigfox is also an operated network in which](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e3e6b75-cfe2-4464-9902-e6012d3f991e-160126111244/75/Sensing-and-controlling-the-environment-using-mobile-network-based-Raspberry-Pis_final-35-2048.jpg)

![28

deployed transceivers (base stations) provide the cellular connectivity to end user

devices. Device transmission is handled by the integrated Sigfox modems in M2M

devices designed to work with the Sigfox network. In figure 16, an M2M device

with an integrated Sigfox modem is regularly transmitting information. The base

station handles the data and routes it to the Sigfox servers which verify data

integrity. Ultimately the information from the servers is received through an API

designed to read the messages from the M2M device.

Figure 16 Sigfox use case

Being an operated network, users only need to purchase the Sigfox compatible

end devices which include specific management applications and APIs. Like the

Weightless-N standard, Sigfox uses patented UNB radio technology for connectivity

and transmission. The communication spectrum is provided by the ISM bands which

further lower the price for maintaining such a network. Sigfox is a frequency

independent network which means that it can comply with any ISM spectrum

depending on location and even with licensed frequencies and white spaces. The

UNB based M2M devices have “outstanding sensitivity” resulting in massive cost

savings allowing cheap subscriptions. Unlike Weightless, Sigfox is a proprietary

network and doesn’t provide much flexibility in terms of adaptability to the rapidly

expanding IoT trend.

Sigfox is differentiated from other competitive technologies by using ultra-low data

rates of 100 b/s [48]. This is advantageous in applications that require very low

throughput and seldom transmissions of data. At the same time, power consumption

is very low allowing end devices to operate up to 20 years with 3 transmissions

per day on a 2.5 Ah battery [48]. Having a very low and fixed data rate, Sigfox

doesn’t present much flexibility when it comes to the large number of different

applications that an IoT network can provide. LPWAN solutions that provide Adaptive

Data Rate (ADR) scale much better in terms of applicability, like Weightless and

Actility. Another downside for Sigfox in contrast with existing solutions is the

proprietary standard which doesn’t allow much flexibility in innovation and slows

down development.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e3e6b75-cfe2-4464-9902-e6012d3f991e-160126111244/75/Sensing-and-controlling-the-environment-using-mobile-network-based-Raspberry-Pis_final-36-2048.jpg)

![29

The Sigfox modems provided by the company are easily integrated in devices

destined for M2M wireless communication. The modems are based on standard

hardware components and have installed the Sigfox protocol stack. Reading Sigfox

messages is done through a web application that allows the user to register

HTTPS addresses of a proprietary IT system with the Sigfox servers. The messages

are then forwarded to the specified HTTPS address [48]. The web application

provides an overview of the network with all connected devices as well as power

status and connectivity issues alongside other relevant data, making the system

easy to access, configure and maintain.

Taking into account the very low power consumption and low throughput, the

network can be characterized as follows [48]:

up to 140 messages/device/day

payload size of 12 bytes/message

data rate of 100 b/s

range:

o rural – between 30 and 50 km

o urban – between 3 and 10 km

o Line of sight propagation to over 1000 km [48]

These characteristics enable a Sigfox BS to handle up to 3 million devices with

the possibility of adding more BS for scalability [48]. Sigfox networks can provide

bi-directional and mono-directional connectivity. In terms of power consumption and

cost, a 1-way communication topology is more efficient. The start network is

deployed such that several antennas can receive a message which significantly

increases reliability and provides a high level of service. Data format is not

specified by Sigfox therefore allowing customers to transmit in their preferred format.

Comparing the network with traditional cellular technology, Sigfox consumes from

200 to 600 times less energy with the same number of devices [48]. The better

signal propagation and coverage results in much lower costs of deployment and

increased speed of deployment. At the moment, Sigfox is deployed in many

countries around Europe including France, The Netherlands, Denmark, and

Luxemburg. Being the first massively deployed IoT network, it has experienced a

huge growth given the need for such a system.

2.5 Summary

The chapter presented above had the goal of detailing the necessary theoretical

aspects required for understanding the current situation of cellular networks and

LPWAN in relation to the IoT. The chapter opened with details about the emerging

new era of widely deployed sensor networks and a possible IoT architecture,

followed by an introduction to short range wireless communication technologies with

details about ZigBee and Bluetooth which have gained a lot of momentum in

recent years due to the technological advances that enabled these technologies to

become feasible on a larger scale. The chapter continues with specifying the more](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e3e6b75-cfe2-4464-9902-e6012d3f991e-160126111244/75/Sensing-and-controlling-the-environment-using-mobile-network-based-Raspberry-Pis_final-37-2048.jpg)

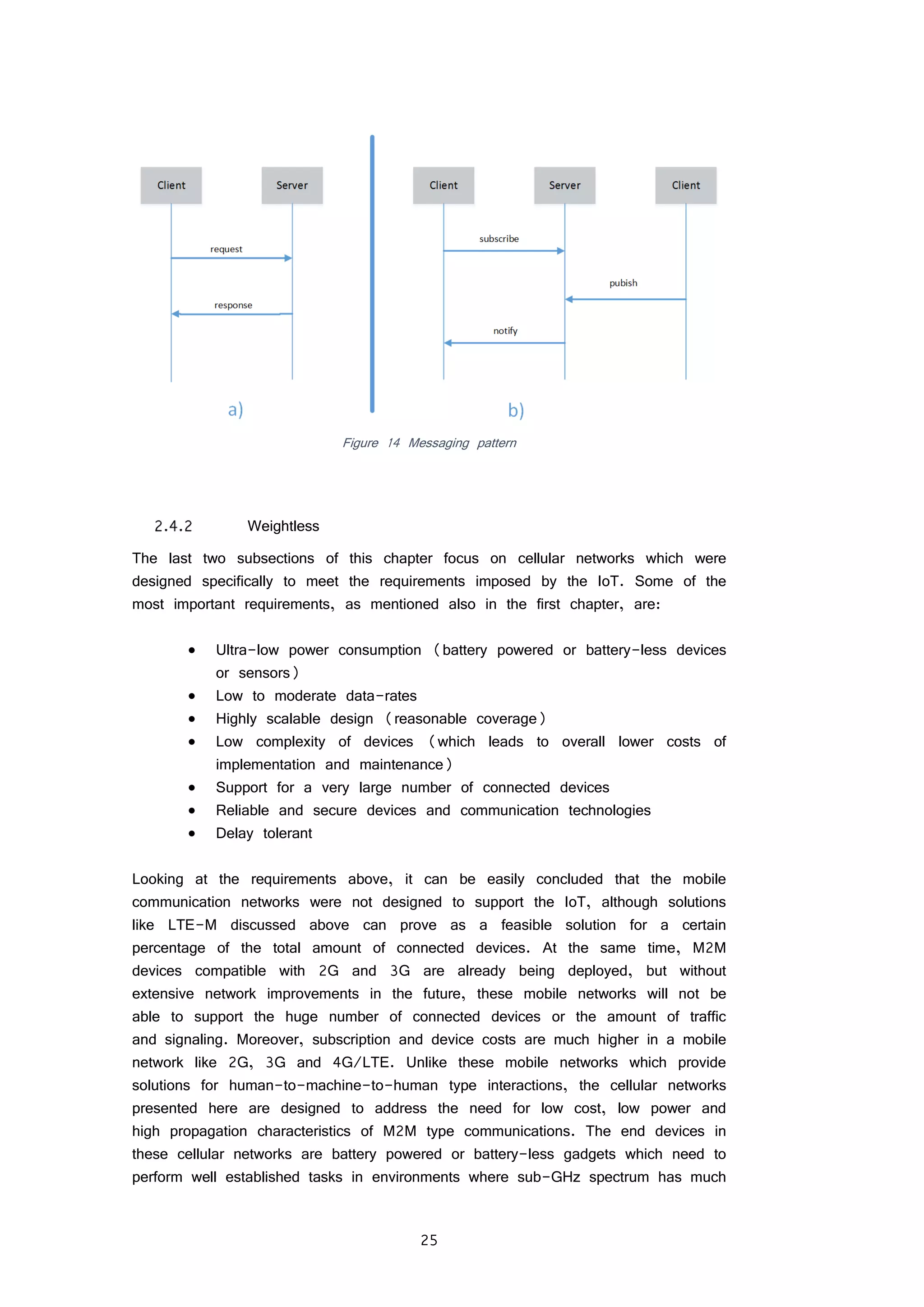

![32

Table 5 TCP compared to UDP [33]

Property UDP TCP

Connection Connectionless Connection-oriented

Reliability

No guarantee for

transmissions

Guaranteed

transmission

Overhead 8 bytes 20 bytes

Retransmissions No Yes

Broadcasting Yes No

The most obvious use of UDP in IoT networks is in 1-way communication systems

where the sent data does not require ACK messages or any other confirmation of

transferred data. This means that information here has no reliability requirements

and can tolerate low latency transfers. The low overhead of UDP datagrams is a

bonus in these cases where transmission time and packet length are critical for

low power consumption networks where device battery life is expected to exceed

10 years. The stateless nature of UDP allows a network running it to accommodate

much more clients than a TCP based network. This is particularly useful since the

IoT is expected to have more than 20 billion devices connected by 2020. The

lower overhead in a UDP based network and the lack of ACK messages results

in larger throughput compared to TCP, which has 2.5 times larger overhead as

seen in table 5 [33]. The flow control mechanisms used by TCP may not be

necessary in M2M connections since the devices do not transmit continuously and

sleep most of the time. The overall performance of the network is also declining

with the use of these reliability mechanisms. Choosing which transport protocol to

use in an IoT network also depends on the application protocol used and some

of these protocols with their associated transport protocol can be seen in table 4.

Another major difference and advantage of UDP over TCP is the broadcasting and

multicasting capabilities, which TCP cannot implement being connection oriented.

Since UDP does not implement reliability, it is then realized at different layers in

the protocol stack if required by the application.

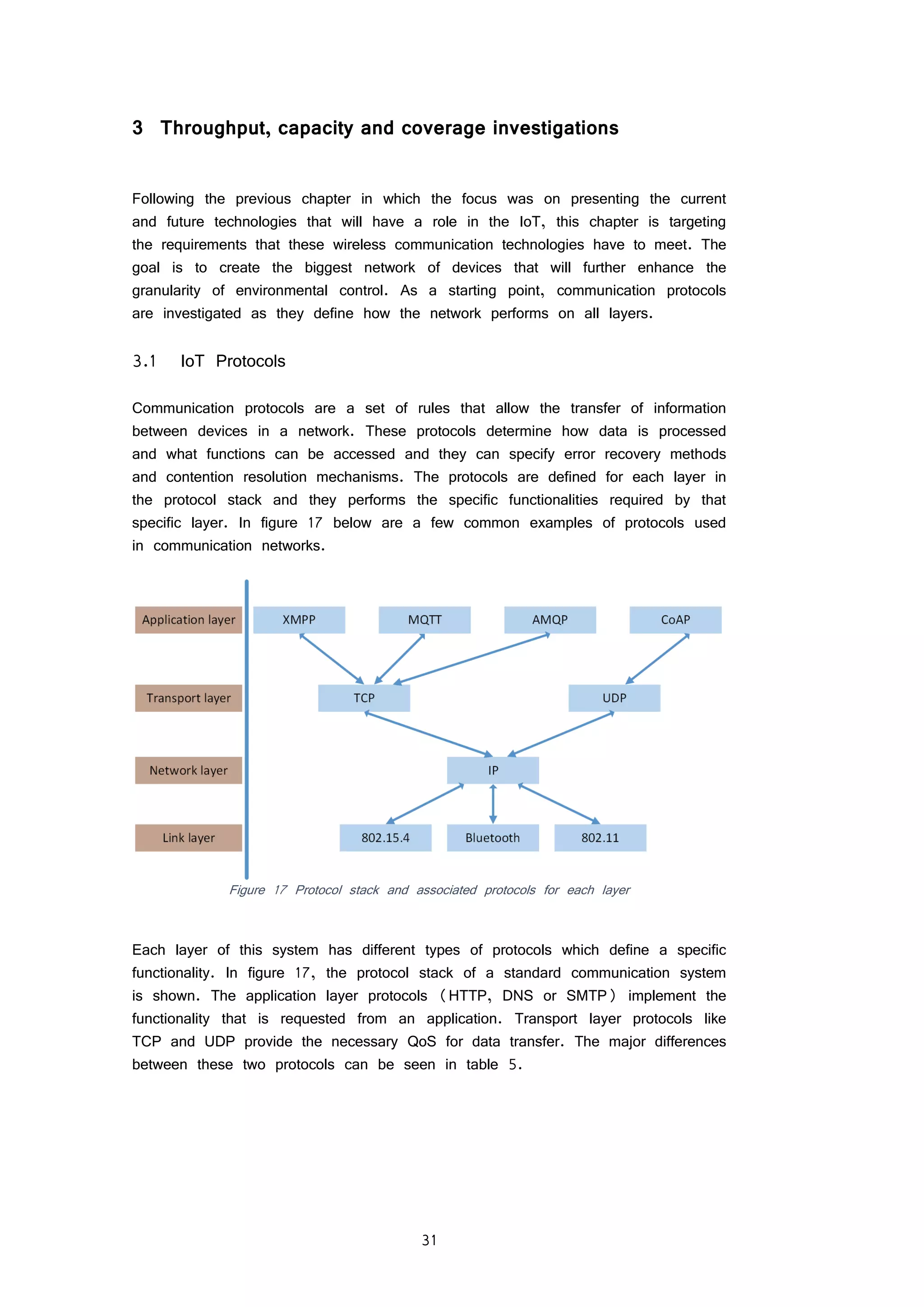

The network layer is responsible with routing data between devices and most

networks today are dominated by the IP protocol. Its task is to transfer packets

between clients and servers and other clients based on a unique address which

is assigned to every network connected device. The link layer is the lowest layer

in the TCP/IP protocol suite and protocols that are used at this layer include

IEEE 802.15.4 and 802.11 as well as Bluetooth. Taking into consideration the

very specific need of M2M devices in an IoT network, some protocols at the

application layer have been identified as a solution for low data rates. Some of

these protocol are: CoAP, MQTT, XMPP, and AMQP. A comparison between these

protocols is shown in table 6. The performance of these protocols was tested in

[38] considering an IoT network.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e3e6b75-cfe2-4464-9902-e6012d3f991e-160126111244/75/Sensing-and-controlling-the-environment-using-mobile-network-based-Raspberry-Pis_final-40-2048.jpg)

![33

Table 6 Comparison of IoT application protocols

CoAP MQTT XMPP AMQP

Messagin

g pattern

Request/Respon

se

Publish/Subscri

be

Publish/Subscri

be

Publish/Subscri

be

Transport

protocol

UDP TCP TCP TCP

Reliability 2 levels of

end-to-end

QoS

3 levels None 3 levels

The choice of protocols for the IoT largely influences network performance,

interoperability and scalability and depending on the requirements of a specific IoT

application, appropriate protocols must be chosen. The application protocols shown

in table 6 can define a certain level of reliability which ultimately defines the

quality of service that a user receives. As UDP does not have a retransmissions

mechanism implemented, the maximum data rate achieved is higher than TCP. At

the same time, the error probability is higher for UDP. Wireless communication

systems are more vulnerable to errors than wired systems and different protocols

have different error probability. For this reason a more detailed investigation

regarding errors in wireless communication is discussed in the next section.

3.2 Errors in wireless communication

In an ideal communication network there are no errors, but in real world scenarios

errors in communication channels are unavoidable. Whether they are caused by

interference, noise or general signal loss, the probability of errors is nonzero. In

wired communication system, errors can be from 10-9

in optical fibre to 10-6

in

copper wires, but in wireless communication systems the error rate can be as

high as 10-3

or worse [33]. Dealing with errors in IoT networks may be very

important or less important depending on the application type so the requirements

of each application vary.

Two of the error control techniques used in communication systems are FEC

(Forward Error Correction) and ARQ (Automatic Repeat Request), the former

uses error detection and correction at the cost of redundant bits and extra

complexity while the latter only detects errors and request retransmissions if were

detected. The FEC method is desired when there is no return channel to request

a retransmission which corresponds to a 1-way communication channel in a WSN.

The FEC method is more appropriate in case retransmissions are not easily

accommodated or are inefficient. In an IoT network, the very large number of

devices will cause a proportional increase in data traffic in case of retransmissions.

This is not desired in such a network due to the extra power consumption of end

devices and extra network traffic. Although FEC demands more complexity in nodes

for error detection and correction, this is easily satisfied in a star topology where](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e3e6b75-cfe2-4464-9902-e6012d3f991e-160126111244/75/Sensing-and-controlling-the-environment-using-mobile-network-based-Raspberry-Pis_final-41-2048.jpg)

![34

central nodes act as base stations which can handle the extra power consumption

and overall complexity.

Due to the functionality of the ARQ protocols for retransmissions, they are very

inefficient in tackling error rates in IoT networks. These protocols produce something

called delay-bandwidth product which results in a product that measures the amount

of lost bits in a specified time frame in which the channel is waiting for a

response before it may retransmit or continue the transmission. The delay-bandwidth

product represents the bit-rate multiplied with the time that elapses (delay) before

an action can take place [33]. The functionality of these protocols may result in

significant “awake” time for end devices that are meant to sleep 99% of the time.

Other error detecting mechanisms use check bits included in packets used by IP,

TCP or UDP.

A more powerful error detecting mechanism is CRC (Cyclic Redundancy Check)

which uses polynomial codes to generate check bits. These bits are added as

redundant information in a packet therefore reducing the total throughput of the

transmission. In order to verify these packets for errors, the check bits are

calculated upon arrival to determine whether the packet contains errors or not.

Packets which contain errors are discarded and retransmitting those packets results

in a further decrease in the overall throughput, which can be estimated by knowing

the BER (Bit Error Rate) of the system and the bit-rate at which information is

exchanged. The following equation can be used to estimate the throughput of a

connection for n-bit packets [57]:

𝑡ℎ𝑟𝑜𝑢𝑔ℎ𝑝𝑢𝑡 = (1 − 𝐵𝐸𝑅) 𝑛

∗ 𝑏𝑖𝑡𝑟𝑎𝑡𝑒

In its simplest form, BER can be calculated by the ratio between the number of

bits received in error and the total number of bits received. There are many

factors that can cause these errors including interference, fading or noise. In

simulation environments, in order to evaluate the performance of a given channel

with respect to BER, models are used based on fading and noise patterns in

different conditions. These models cannot perfectly simulate the environment, but

they provide enough accuracy in order to estimate the requirements for the simulated

system. Two models that are used to simulate white noise and fading channels

are AWGN (Additive White Gaussian Noise) and Rayleigh fading. In order to

observe the difference between these two models in relation to the BER, a

simulation was conducted in Matlab. The simulation was done for modulation

formats BPSK and QPSK and it can be observed in figure 18, below. It should

be noted that the simulation was done comparing BER with Eb/No which is the

SNR per bit and it is different than SNR. Eb/No is a normalized SNR which is

used when comparing the BER of different modulation formats without considering

bandwidth [72]. The equations used to describe these two fading models in the

simulation are the theoretical BER for BPSK over Rayleigh fading channel with

AWGN [71]:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e3e6b75-cfe2-4464-9902-e6012d3f991e-160126111244/75/Sensing-and-controlling-the-environment-using-mobile-network-based-Raspberry-Pis_final-42-2048.jpg)

![35

𝐵𝐸𝑅 =

1

2

∗ (1 − √

𝐸𝑏

𝑁𝑜

1 +

𝐸𝑏

𝑁𝑜

)

And the theoretical BER for BPSK over an AWGN channel [71]:

𝐵𝐸𝑅 =

1

2

∗ 𝑒𝑟𝑓𝑐(√𝐸𝑏/𝑁𝑜)

Figure 18 BER for BPSK and in Rayleigh and AWGN channels

Figure 18 shows a large difference between the two channel models used to

describe the BER. The difference is explained by the fact that AWGN only adds

white noise to the channel which is not sufficient to counter the obstacles in a

path, while the Rayleigh fading model is a statistical model that takes into account

many objects that can fade the propagating signal considerably. The fading of a

signal is described in more detail in the link budget section below.

In addition to a BPSK signal, a simulation was also conducted regarding a QPSK

signal, for which theory says it is supposed to be twice as effective in terms of

bandwidth and bits/symbol. But the results shown in figure 19 say otherwise. The

reason for this result stands in the fact that the simulation is conducted for BER

as a function of Eb/N0, which is not the same as the SNR. Eb/N0 is the ratio

of bit energy to the spectral noise density and it represents a normalized SNR

measure which is also known as SNR per bit. That being said, Eb represents the

energy associated with each user data bit and N0 is the noise power in a 1 Hz

bandwidth, so the difference between SNR and the SNR per bit is that SNR is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e3e6b75-cfe2-4464-9902-e6012d3f991e-160126111244/75/Sensing-and-controlling-the-environment-using-mobile-network-based-Raspberry-Pis_final-43-2048.jpg)

![36

considered for the whole channel while the Eb/N0 is considered for each individual

bit [74]. So BPSK and QPSK have the same BER as a function of Eb/N0

because, when not taking bandwidth into consideration, they perform the same,

although QPSK requires half the bandwidth of BPSK for the same data rate. The

representation of this is shown in figure 19 below.

Figure 19 BER for a BPSK and QPSK signal in an AWGN channel

Beside bit-errors, other causes of failed transmission/reception can result from

colliding packets of information transmitted on the same frequency in the same

time interval. The ZigBee protocol uses CSMA-CA method to avoid collisions in a

highly used 2.4 GHz band where interference and collisions are unavoidable. This

method also has its limitations and the hidden terminal problem may result in lost

packets in a transmission. This functionality of this method allows transmitters to

listen while sending packets in order to avoid collisions, but this results in much

smaller received signal strength, which can directly influence the coverage of the

network as well as transmission power. At the same time, device costs are

increased due to the implementation of this mechanism.

The quality of the transmission is not only influenced by the BER and the next

section of this chapter introduces the concept of link budget which plays an

important role in establishing a reliable communication distance between BS and

MS/end-device.

3.3 Link budget

The link budget is an important network parameter that determines the coverage

of a BS. In order to determine how far a mobile-user/end-device can be from](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e3e6b75-cfe2-4464-9902-e6012d3f991e-160126111244/75/Sensing-and-controlling-the-environment-using-mobile-network-based-Raspberry-Pis_final-44-2048.jpg)

![37

the base station, the path loss is calculated by subtracting the BS receiver

sensitivity from the device’s transmit power while also considering fading, other

losses and possible gains in order to provide an accurate margin. The link budgets

for devices in an IoT network that are meant to penetrate thick walls and basements

have an increase of 15 to 20 dB (depending on technology) [16, 51] to ensure

signal propagation.

In a RF LOS (Radio Frequency Line Of Sight) environment, the same link budget

is equivalent to a significant increase in coverage compared to fading environments.

The link budget is calculated using the equation below.

𝑅𝑒𝑐𝑒𝑖𝑣𝑒𝑑 𝑃𝑜𝑤𝑒𝑟 (𝑑𝐵𝑚) = 𝑇𝑟𝑎𝑛𝑠𝑚𝑖𝑡𝑡𝑒𝑑𝑃𝑜𝑤𝑒𝑟 (𝑑𝐵𝑚) + 𝐺𝑎𝑖𝑛𝑠(𝑑𝐵) − 𝐿𝑜𝑠𝑠𝑒𝑠(𝑑𝐵)

The losses in the above equation can be expressed as a sum of the total losses

experienced by a wireless link which can account for FSPL and fading due to

objects in the way. When the signal is propagating in LOS, the FSPL (Free-

Space Path Loss) is the main contributor to decreased signal power over distance.

This value is “proportional to the square of the distance between the transmitter

and receiver as well as the square of the frequency of the radio signal” [52].

The FSPL is calculated with the following formula:

𝐹𝑆𝑃𝐿(𝑑𝐵) = 10 log10 (

4𝜋𝑑𝑓

𝑐

)

2

Where f is the frequency in Hz, d is the distance in meters and c is the speed

of light in vacuum (3*108

m/s). The graph showing the FSPL for the 900 MHz

and 2.4 GHz band is shown below.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e3e6b75-cfe2-4464-9902-e6012d3f991e-160126111244/75/Sensing-and-controlling-the-environment-using-mobile-network-based-Raspberry-Pis_final-45-2048.jpg)

![38

Figure 20 Free Space Path Loss in 900 MHz and 2.4 GHz bands

Considering that the majority of network areas in an urban environment are not

LOS, a different model for calculating the path loss is used, the Okumura-Hata

model for outdoor areas given by the following mathematical formulation [74]:

𝐿 𝑈[𝑑𝐵] = 69.55 + 26.16 log10 𝑓 − 13.82 log10 ℎ 𝐵 − 𝐶 𝐻

+ [44.9 − 6.55 log10 ℎ 𝐵]log10 𝑑

Where for small and medium sized cities:

𝐶 𝐻 = 0.8 + (1.1 log10 𝑓 − 0.7) ∗ ℎ 𝑀 − 1.56 log10 𝑓

And for large cities

𝐶 𝐻 = {

8.29(log10(1.54 ℎ 𝑀))2

− 1.1, 𝑖𝑓 150 ≤ 𝑓 ≤ 200

3.2 (log10(11.75ℎ 𝑀))2

− 4.97, 𝑖𝑓 200 < 𝑓 ≤ 1500

}

Where

𝑳 𝑼 Path loss in urban area [dB]

𝒉 𝑩 Height of BS [m]

𝒉 𝑴 Height of MS antenna [m]

𝒇 Transmission frequency [MHz]

𝑪 𝑯 Antenna height correction factor

𝒅 Distance between the base and mobile stations [km]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e3e6b75-cfe2-4464-9902-e6012d3f991e-160126111244/75/Sensing-and-controlling-the-environment-using-mobile-network-based-Raspberry-Pis_final-46-2048.jpg)

![39

The Okumura-Hata path loss model for the 900 MHz band is shown in figure 21

and for the 2.4 GHz band is shown in figure 22.

Figure 21 Okumura Hata path loss model for 900 MHz for several scenarios with different

antenna heights [m]

Figure 22 Okumura Hata path loss model for 2.4 GHz for several scenarios with different

antenna heights [m]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3e3e6b75-cfe2-4464-9902-e6012d3f991e-160126111244/75/Sensing-and-controlling-the-environment-using-mobile-network-based-Raspberry-Pis_final-47-2048.jpg)

![40

The path loss models described above are only valid for outdoor environments.

The ITU (International Telecommunication Unit) have described an indoor

propagation model valid for frequencies in the range of 900 MHz and up to 5.2

GHz and for a building having up to 3 floors [76]. The model is described in

the equation below:

𝐿 = 20 log10 𝑓 + 𝑁 log10 𝑑 + 𝑃𝑓(𝑛) − 28

Where

𝑳 Total path loss indoor [dB]

𝒇 Transmission frequency [MHz]

𝒅 Distance [m]

𝑵 Distance power loss coefficient

𝒏 Number of floors between transmitter and receiver

𝑷 𝒇(𝒏) Floor loss penetration factor