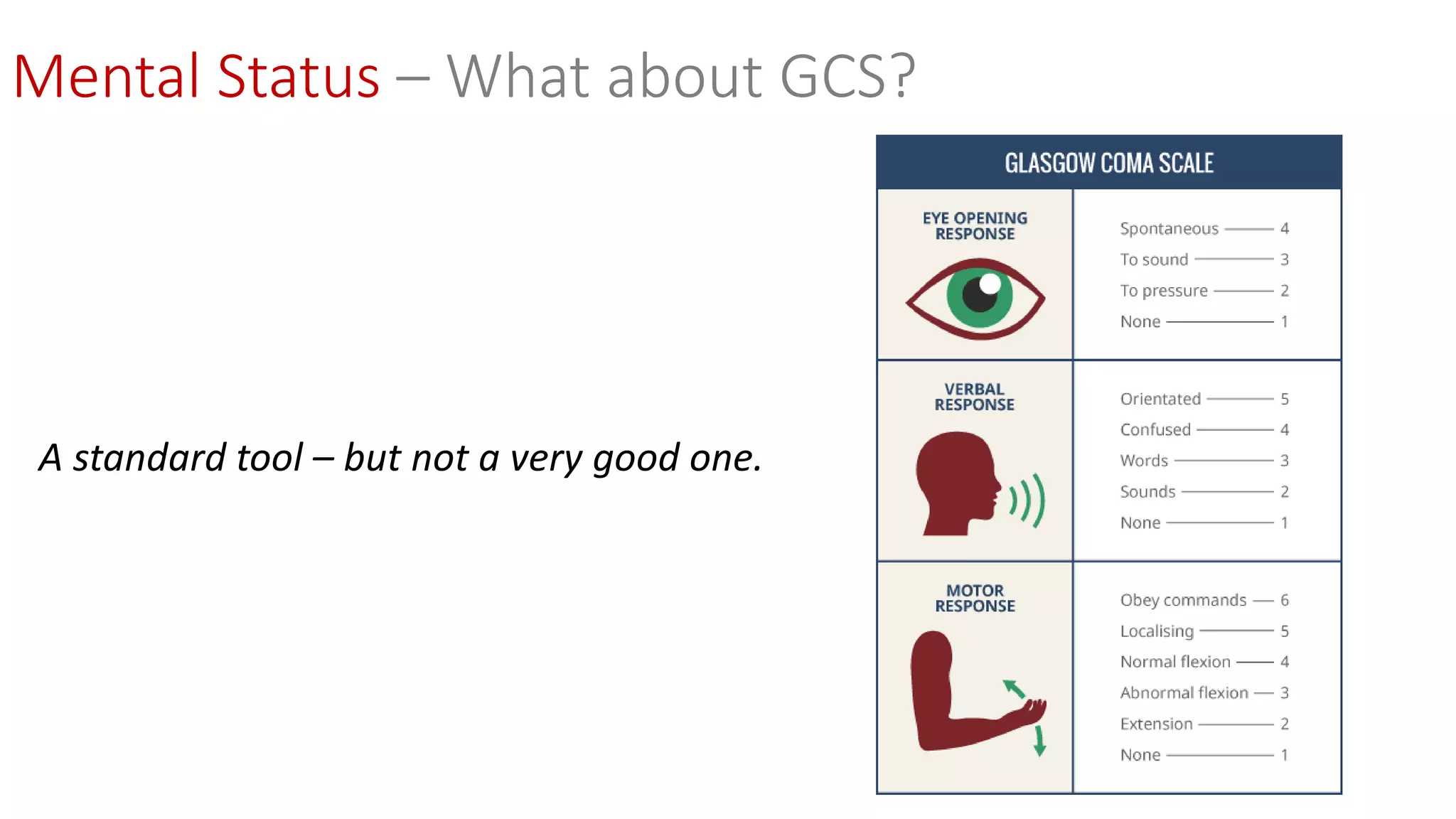

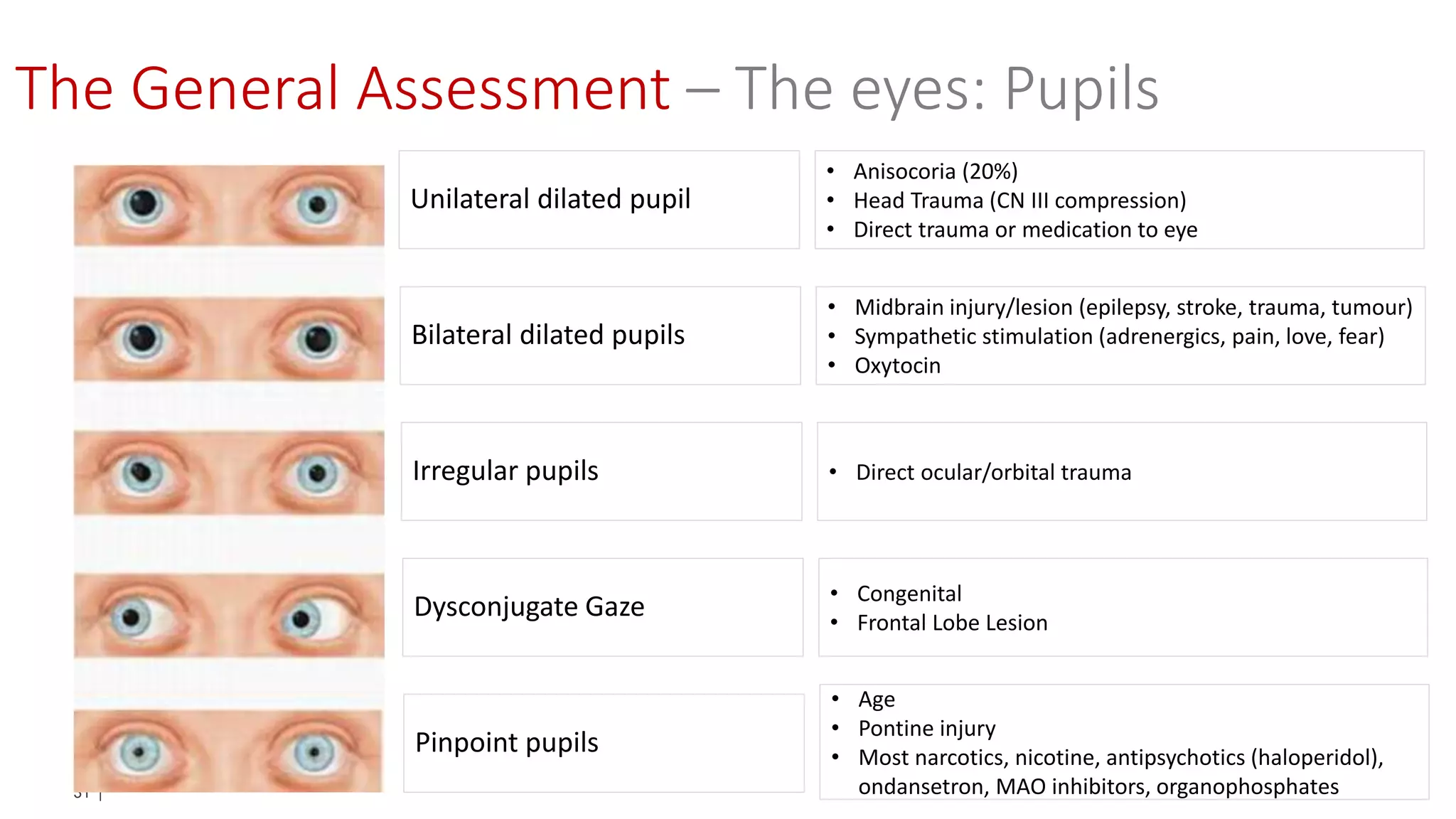

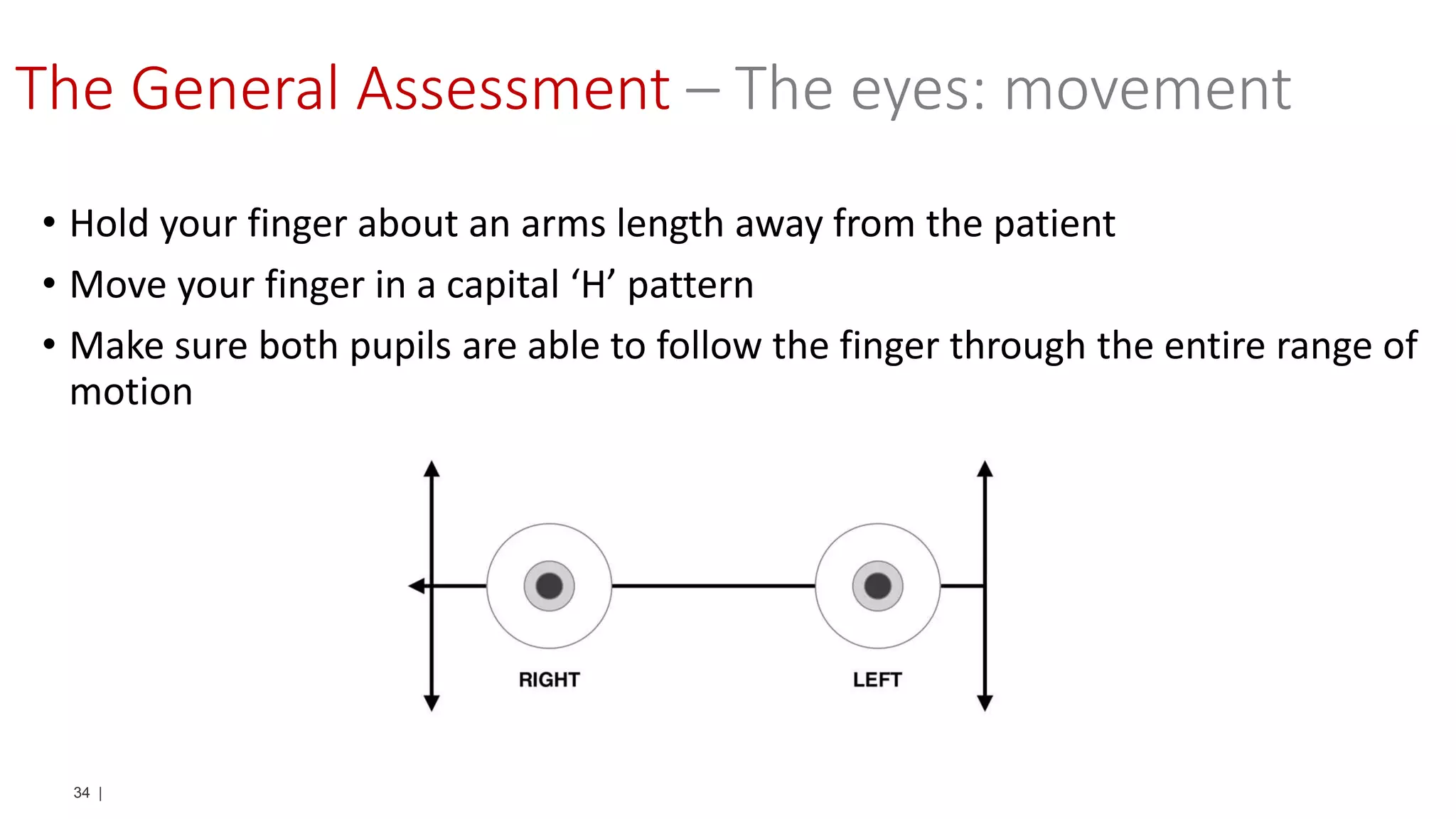

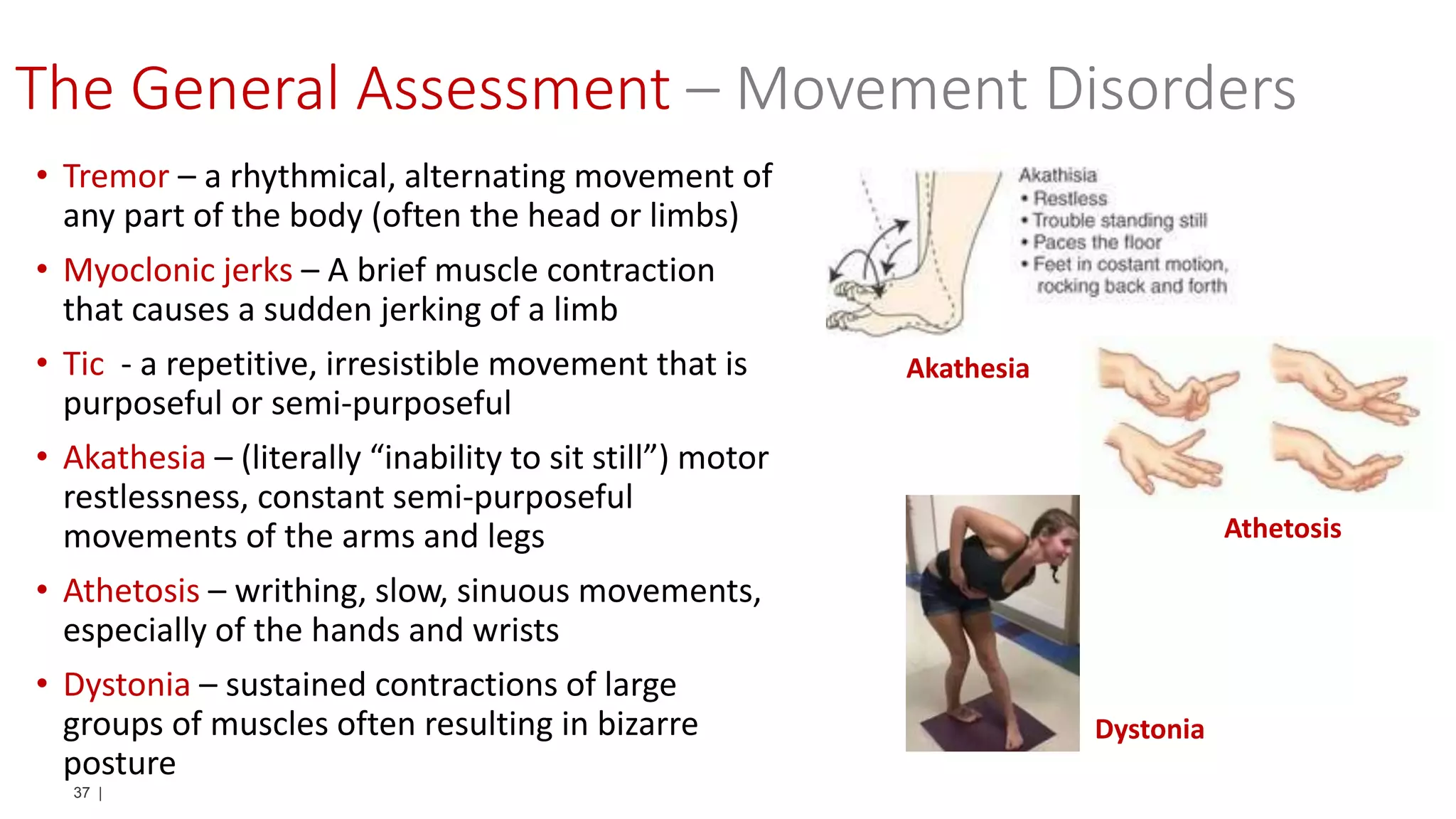

The document provides a detailed overview of neurological assessments for paramedics, including mental status evaluation, eye examinations, and cranial nerve assessments. It emphasizes the importance of accurately determining a patient's neurological condition through various tests and symptoms, using a case study of actress Natasha Richardson to illustrate the risks associated with missed diagnoses. Additionally, it critiques the use of the Glasgow Coma Scale and recommends alternative assessment methods for more reliable results.