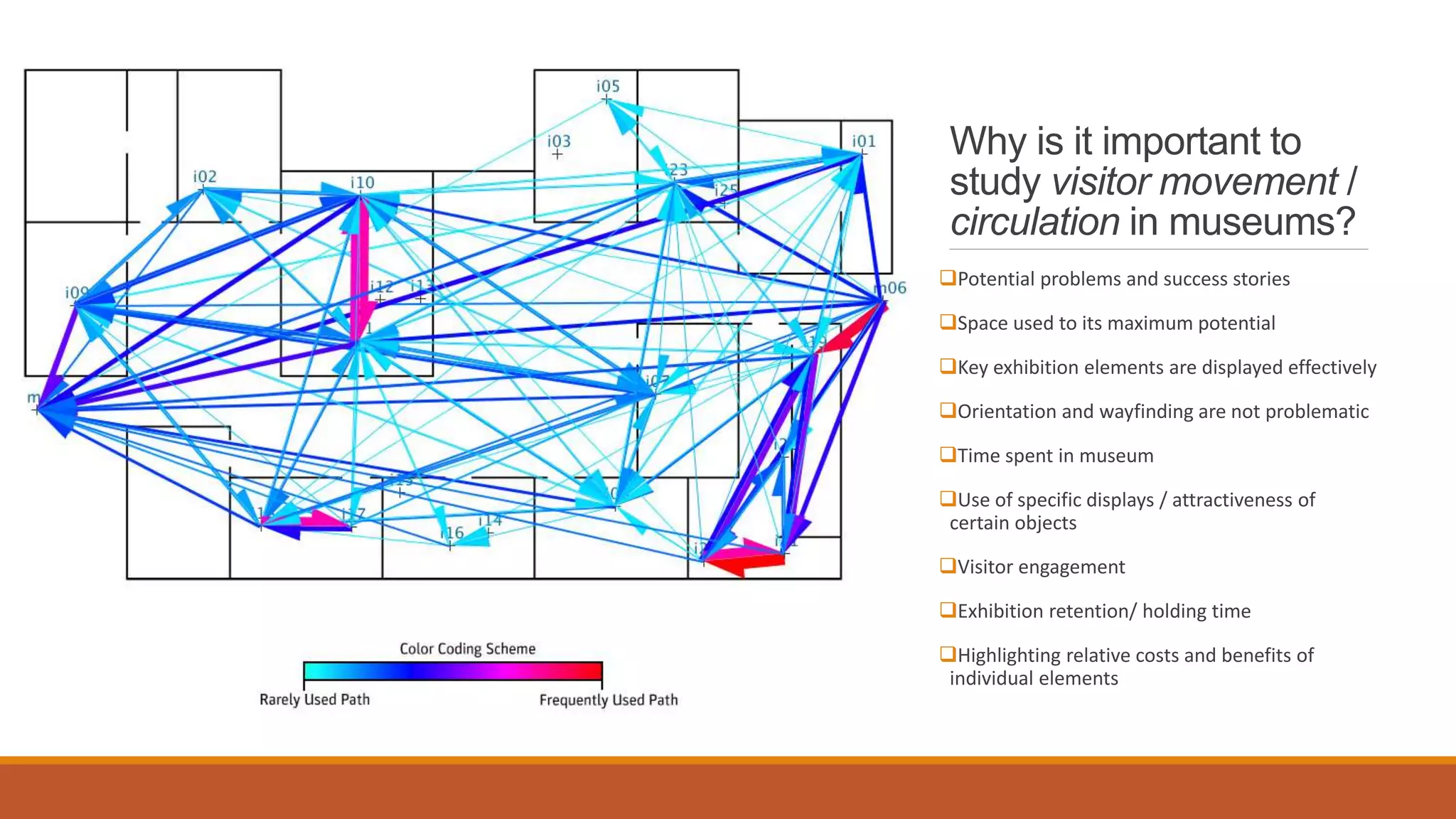

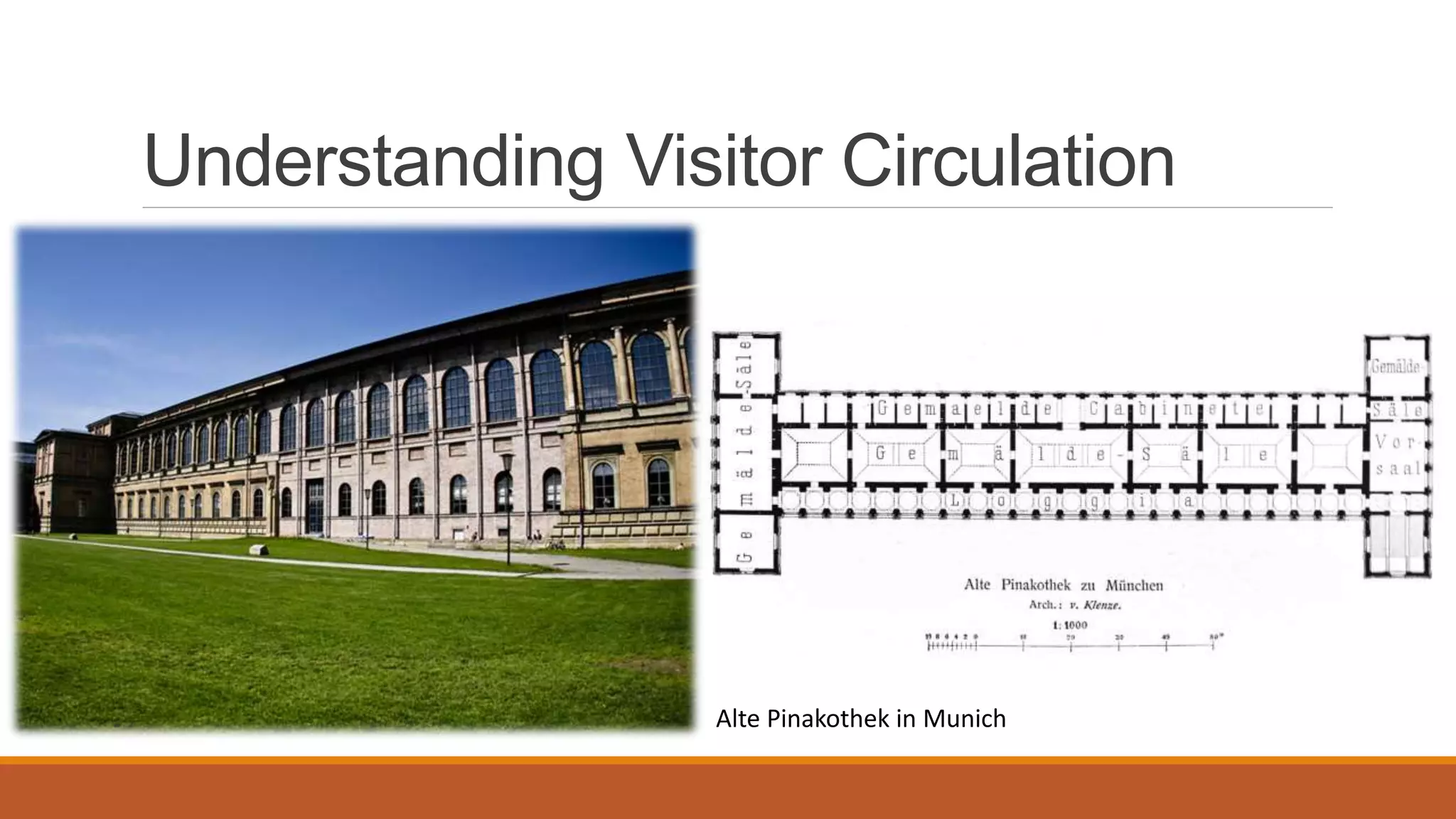

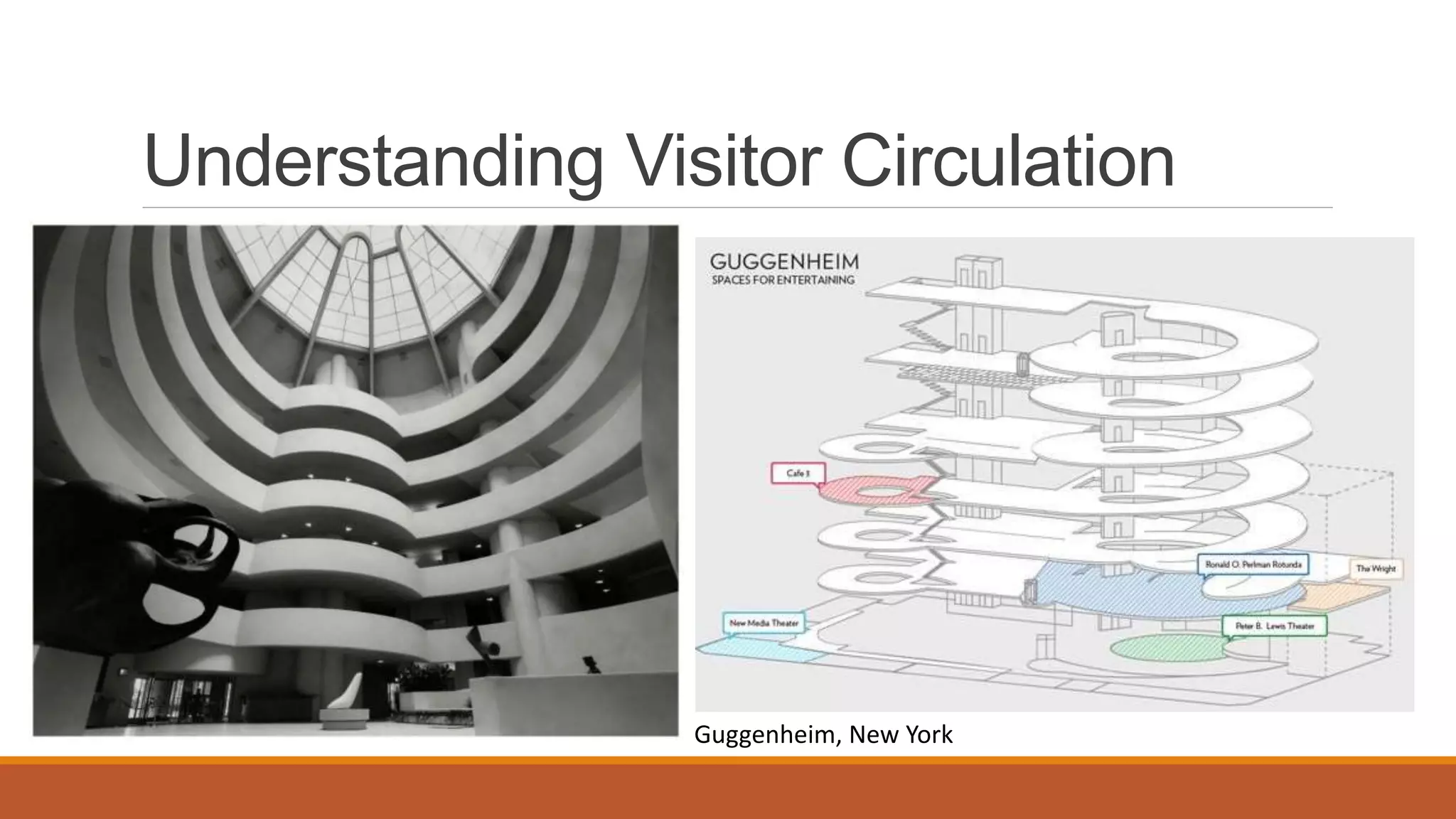

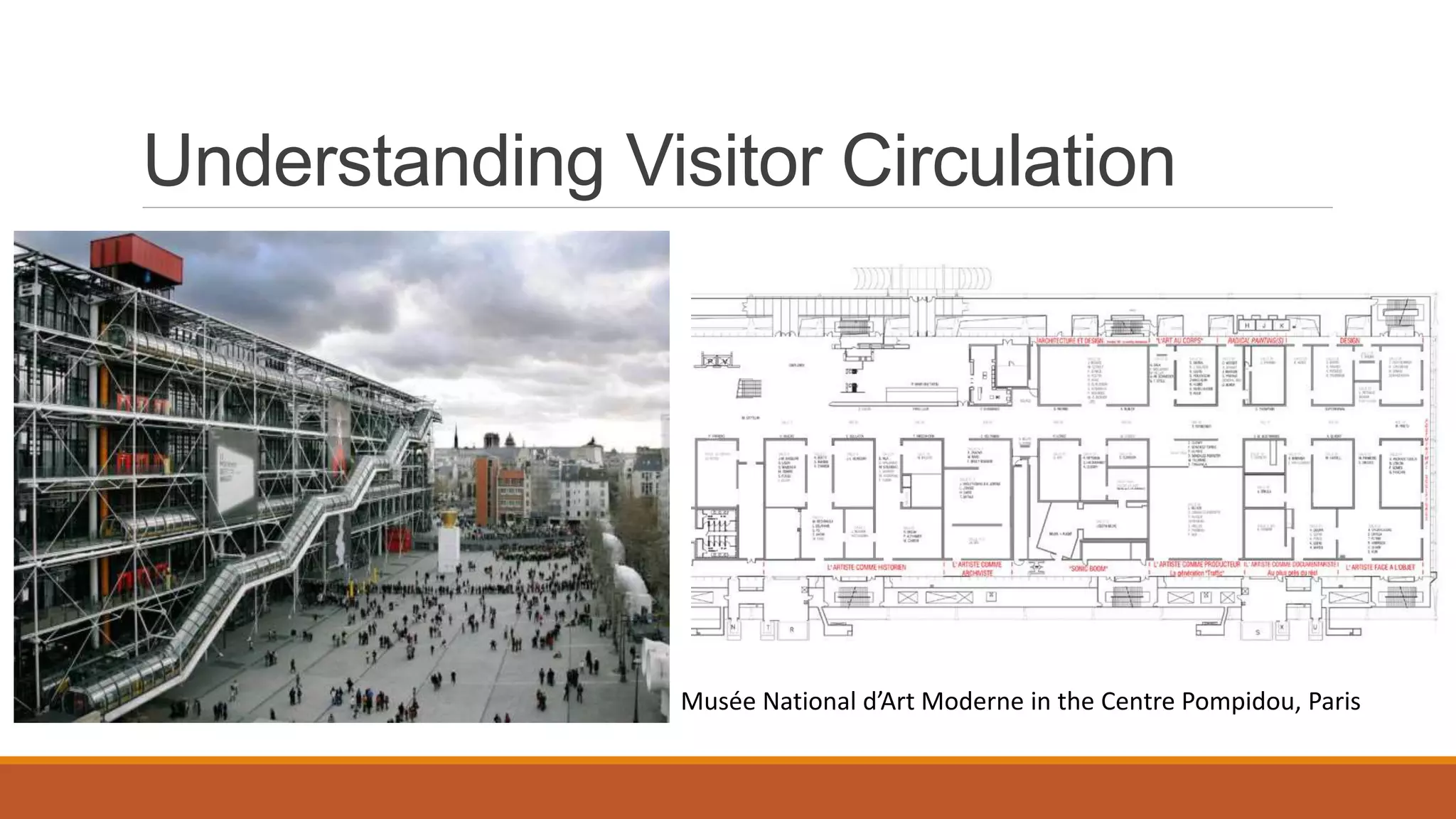

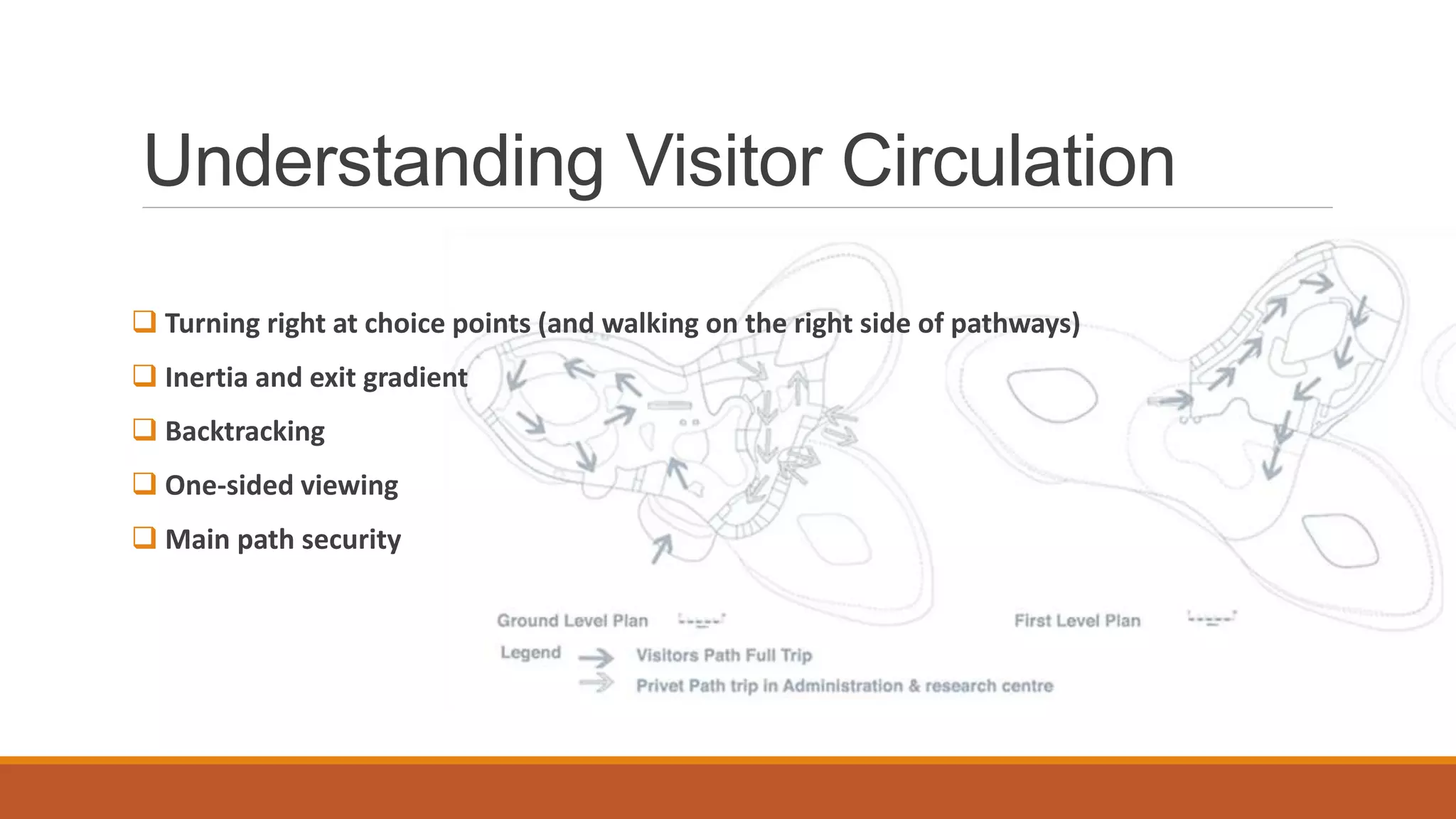

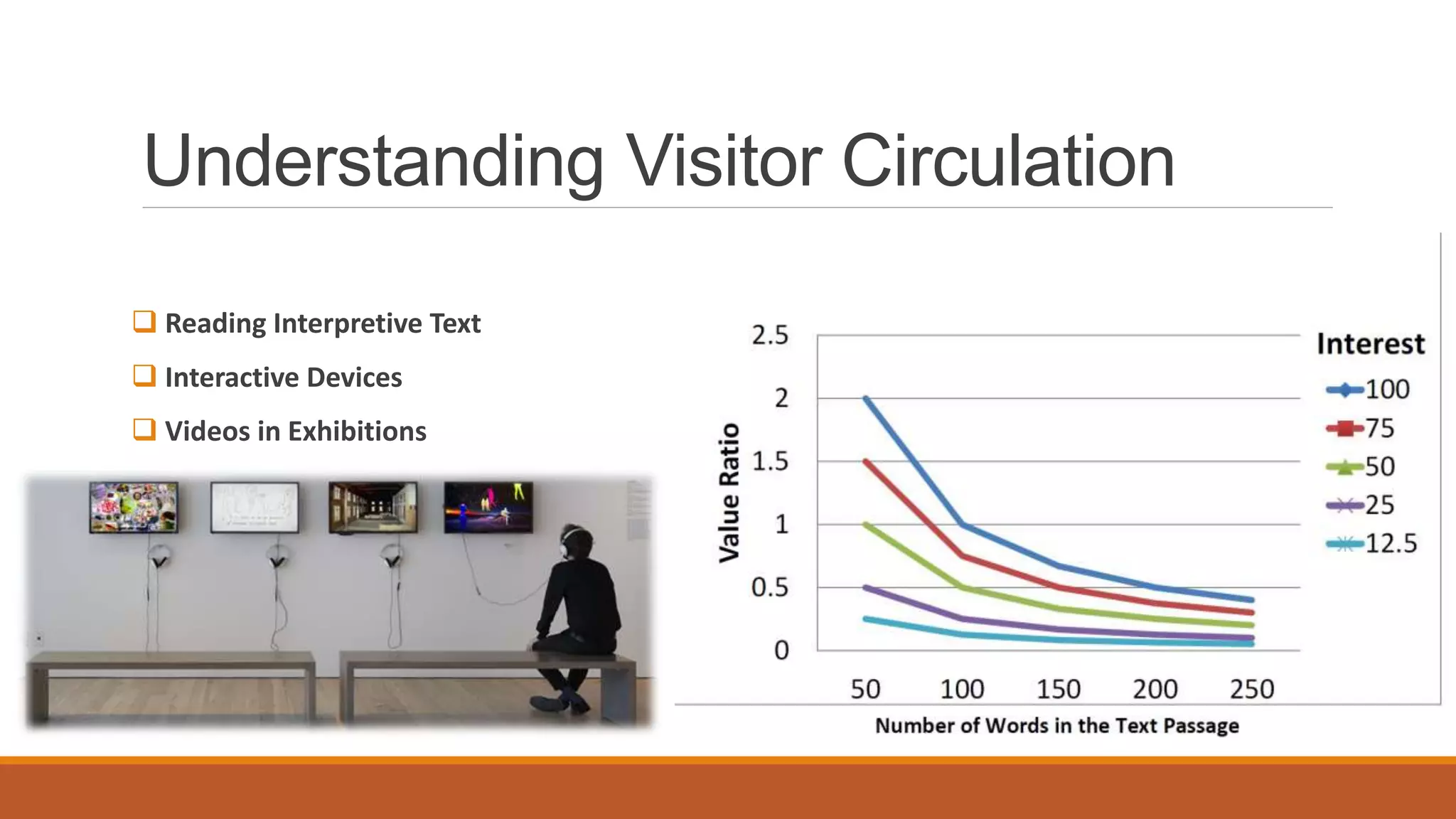

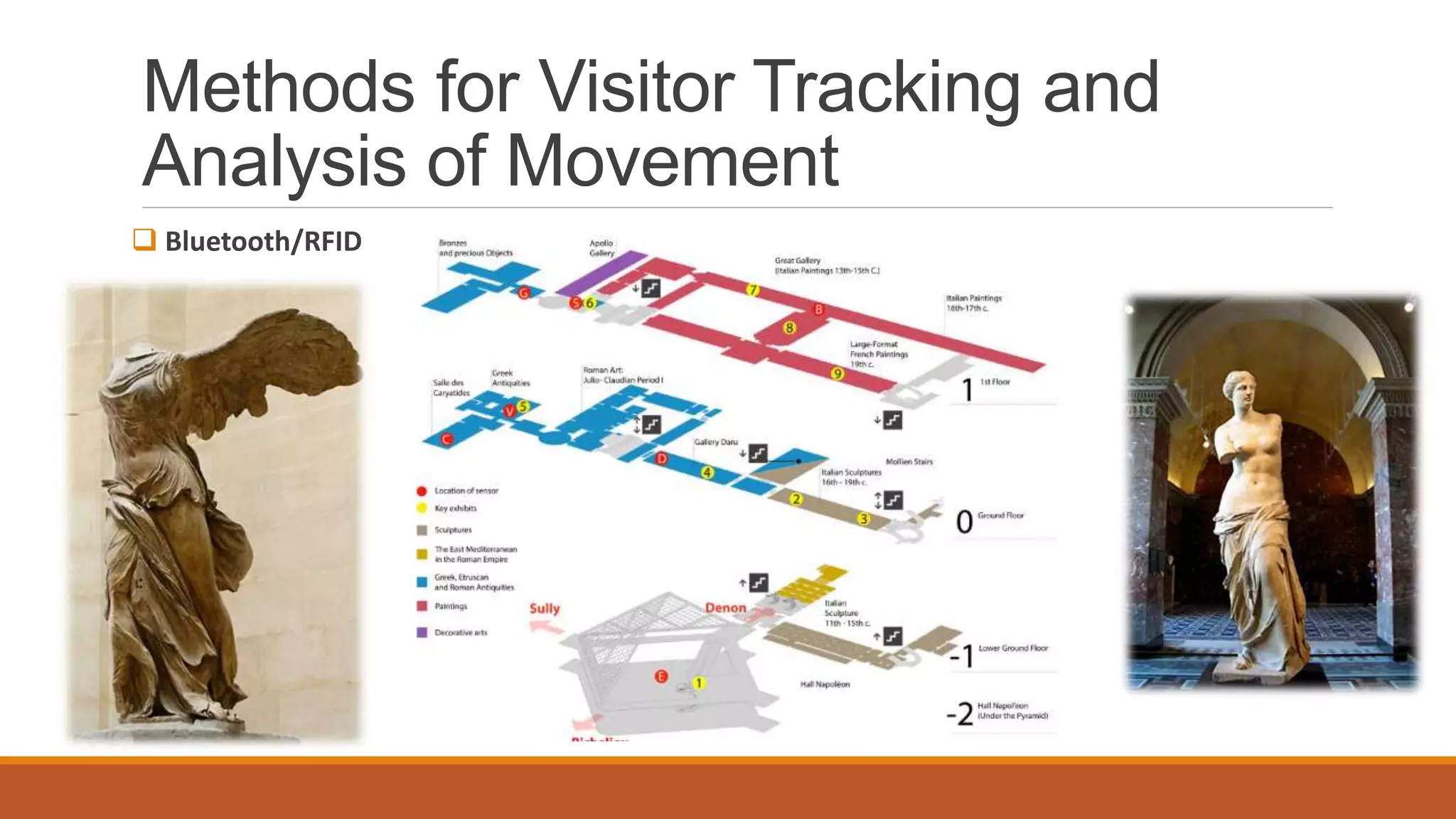

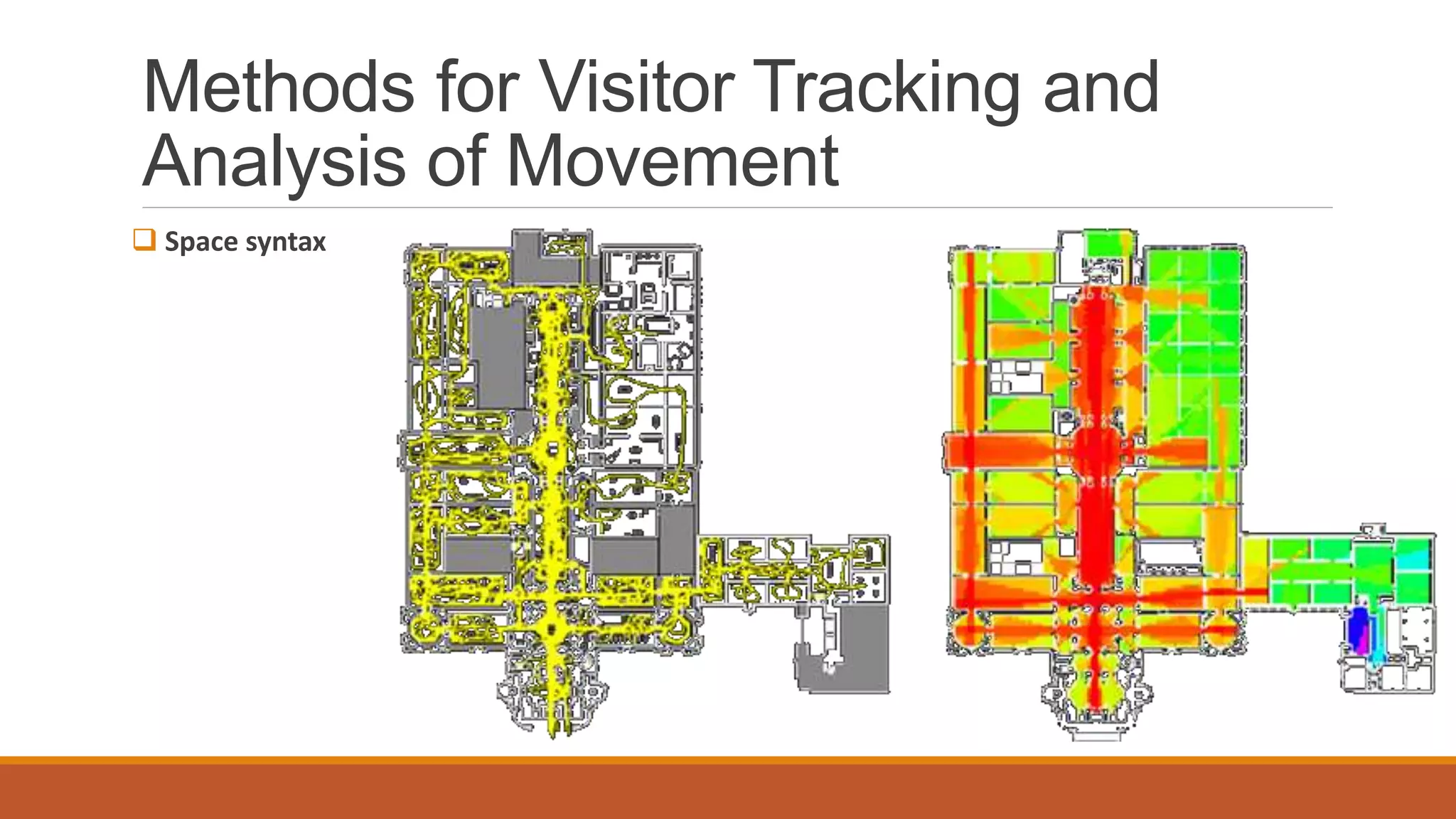

This document discusses the significance of studying visitor movement and circulation in museums, highlighting its impact on maximizing space usage, enhancing visitor engagement, and improving exhibition effectiveness. It emphasizes that visitors do not always follow intended exhibit sequences, showcasing the importance of understanding their behavior patterns and preferences. Various methods for tracking visitor movement, such as observational studies and technology integration, are also presented to aid in analyzing visitor interaction with exhibits.