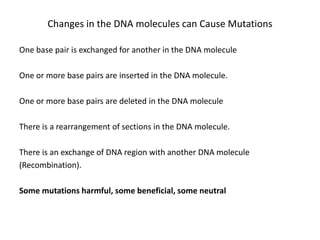

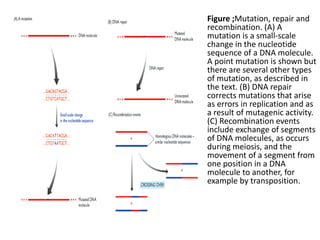

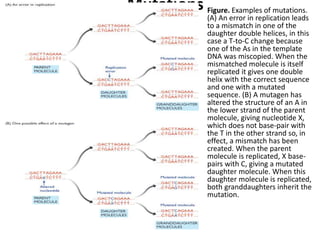

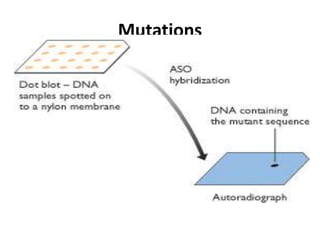

1. Mutations are changes in the nucleotide sequence of DNA that can arise spontaneously during DNA replication or due to damage from mutagens.

2. DNA repair enzymes work to minimize mutations by correcting errors during replication or reacting to damaged DNA.

3. If a mismatch introduced during replication is not repaired, it will become a permanent mutation when that region is replicated again.