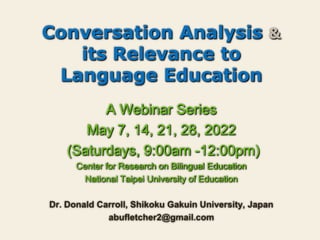

Conversation Analysis and its Relevance to Language education

- 1. A Webinar Series May 7, 14, 21, 28, 2022 (Saturdays, 9:00am -12:00pm) Center for Research on Bilingual Education National Taipei University of Education Dr. Donald Carroll, Shikoku Gakuin University, Japan abufletcher2@gmail.com Conversation Analysis & its Relevance to Language Education

- 2. An introduction to Conversation Analysis

- 3. What CA is… …a fundamentally different way of looking at and explicating human interaction. …a robust (and rigorous) research methodology that looks more deeply at the fine-grained details of life than any other perspective. …an extensive body of empirical research, now well into its sixth decade, into the observable micro-practices of talk-in-interaction. …a window out onto an entirely different view of the nature of language and, therefore, how language might be taught. …the relevant “body of knowledge” on which the teaching of spoken interaction should be based.

- 4. What CA isn't… …It isn’t a set of “rules for having good conversation” or “rules for how to speak politely.” It's not rules at all. …It isn’t just another name for “discourse analysis” though the two research fields/paradigms share many common goals. …It isn’t just recording some talk, then writing it down, which is to say, it’s not reducible to a simple series of mechanical or technological steps. …It isn’t a language teaching methodology, akin to, say, the “communicative approach.”

- 5. Analysis of Conversational Data (ACD) vs. Ethnomethodological CA (SSJ CA) Sacks, Schegloff, and Jefferson (1974)

- 10. Domains of interactional organization Turn-taking How do participants take turns in conversation? Turn-construction How are turns-at-talk structured, produced, and perceived? Sequence organization How are single turns-at-talk organized into sequences of turns? Preference organization How do participants in talk-in-interaction manage social challenges? Practices of repair How are threats to intersubjectivity handled in interaction? Action formation How do conversational actions come to be recognized?

- 11. CA has examined real- world, situated interaction at a resolution previously unimaginable. …from close looking at the world we can find things that we could not, by imagination, assert were there. (Sacks, 1984:25)

- 12. "…from close looking at the world we can find things that we could not, by imagination, assert were there." (Sacks, 1984:25)

- 13. Sample of CA transcription …from close looking at the world we can find things that we could not, by imagination, assert were there. (Sacks, 1984:25)

- 14. CA: The Basics

- 16. In any conversation, people take turns talking. Otherwise, it wouldn’t be a conversation. How is turn-taking organized?

- 17. Pre-allocated turn-taking In bowling everyone agrees before the game begins who will bowl first, second, third, and so on. This sort of turn-taking is called "pre-allocated." For some types of social events the speaking order is decided in advance or follows a strict set of established rules. Examples would be a graduation ceremony, a formal debate, and courtroom proceedings. In some cultures, in some (formal) settings, there might also be societal rules for pre-allocation of turns-at-talk, for example, based on seniority or social rank.

- 18. Turn-taking systems There is also the sort of turn-taking common to classrooms, in which the teacher manages who speaks, either by calling on a particular student or allowing students to "nominate" themselves by raising a hand, after which the teacher selects one of them. However, most talk does not follow a system of pre-allocated turn-taking. This includes most spoken interaction (i.e. "talk- in-interaction") ranging from casual conversation to the myriad varieties of talk-at-work (and even in classrooms). On these occasions, we say that the turn-taking is "locally managed" turn by turn. It is not decided in advance. But how is this accomplished?

- 19. The signal model In some types of communication a signal is used to mark the end of a speaking turn. This is the case with walkie-talkies and CB-type radios. Both operate on a push-to-talk basis. A: The operation begins at 0600. Over. ((releases button)) B: Affirmative. Over. ((releases button)) A: Good luck. Over and out. ((releases button, shuts off)) One proposal for a system of conversational turn-taking is the so-called "signals" model, in which the ends of speaking turns are "marked" via various linguistic features, including silence. According to this model, other participants wait for these signals, which indicate that the current speaking is going to "yield the floor" to another participant (Duncan, 1974; Duncan and Fiske, 1977).

- 20. CA and the SSJ system A different description of conversational turn-taking, which more closely matches observations of recorded natural- occurring interaction, was laid out by Harvey Sacks, Emanuel Schegloff and Gail Jefferson (1974) in their now- classic CA paper: “A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation.” The SSJ turn-taking system better accounts for 1) the empirical fact that next speakers are able to begin speaking with little or no-gap between turns, 2) the common occurrence around points of possible transition of natural overlap, 3) not just of how transition happens but also how a given next speaker comes to have rights to the turn.

- 21. TRP projection

- 22. Some resources for TRP projection* • Syntax • Prosody • Pragmatics • Gaze and other embodiment • Habitual phrasing (?)** A: Well if you knew my argument why did you bother= =to a:[sk B: [because I'd like to defend my argument. *The subtle, but important, distinction is that in the SSJ system, possible next speakers are projecting possible NOT ACTUAL completion. **See Jefferson 1986 on "recognitional onset."

- 23. CA and the SSJ system 1a. Current speaker may, but need not, select next speaker. 1b. If current speaker does not select next speaker, a next speaker may, but need not, self-select by speaking first.* 1c. If no other participant self-selects, current speaker may, but need not, speak again. This can also be worded as Current speaker may, but need not, continue speaking. 2. Rules 1a, 1b, and 1c continue to apply in this order at every possible transition relevance place until speaker transfer occurs. *Research suggests that participants may also make claims on next speakership via various forms of embodiment.

- 24. Let's try out Rule 1b: Self-selection 1) THE COUNTING GAME 2) I LIKE… 3) I WANNA GO TO…

- 25. CA and the SSJ system 1a. Current speaker may, but need not, select next speaker. 1b. If current speaker does not select next speaker, a next speaker may, but need not, self-select by speaking first.* 1c. If no other participant self-selects, current speaker may, but need not, speak again. This can also be worded as Current speaker may, but need not, continue speaking. 2. Rules 1a, 1b, and 1c continue to apply in this order at every possible transition relevance place until speaker transfer occurs. *Research suggests that participants may also make claims on next speakership via various forms of embodiment.

- 26. A new TCU vs. an increment 1c Current speaker may speak again. J: I went shopping yesterday (.) I was looking for some hiking boots. (.) Some friends are going to Nagano next month. 1c Current speaker my continue speaking. (Adding increments) J: I went shopping yesterday. (.) to look for some hiking boots. (.) Since some friends are going to Nagano next month.

- 27. CA and the SSJ system 1a. Current speaker may, but need not, select next speaker. 1b. If current speaker does not select next speaker, a next speaker may, but need not, self-select by speaking first.* 1c. If no other participant self-selects, current speaker may, but need not, speak again. This can also be worded as Current speaker may, but need not, continue speaking. 2. Rules 1a, 1b, and 1c continue to apply in this order at every possible transition relevance place until speaker transfer occurs. *Research suggests that participants may also make claims on next speakership via various forms of embodiment.

- 29. Adjacency pairs One mundanely observable feature of talk-in-interaction is that prior turns often place limitations on the sorts of turns that might expectably occur next. This relationship is broadly referred to as conditional relevance. Harvey Sacks, one of the founders of Conversation Analysis, coined the term adjacency pairs (AP) in the late 60's for pairs of turns, which are regularly found (in recorded talk) next to each other. The two halves of an AP are referred to as the first-pair part (1PP) and the second-pair part (2PP). Sacks et al. (1974:716-8) summed up the operation of an AP as follows: "A basic rule of adjacency pair operation is: given the recognizable production of a first pair part, on its first possible completion its speaker should stop and a next speaker should start and produce a second pair part from the pair type of which the first is recognizably a member."

- 30. Adjacency pair as normative expectation There are no hard and fast rules in conversation that participants MUST follow…only normative expectations. Following a greeting one can expect a greeting in return. This is such a strong expectation that, if no greeting is forthcoming, participants, can treat it as officially missing and search for a reason. Was the greeting not heard? Was the person otherwise engaged? Or was this an outright refusal to do a greeting…and thus initiate a conversation? Participants also use the normative expectations of adjacency pair organization to interpret the next turn. A question (i.e. a request for information) sets up an expectation for an answer. As such whatever talk that occurs in the slot following a question will be inspected as a possible answer. Thus, an adjacency pair serves as an interpretive frame. A: How late does the hardware store stay open? B: It's Monday.

- 31. Common adjacency pairs (Levinson 1983:303) 1PP greeting 2PP greeting A: Hi B: Hi 1PP question 2PP answer A: What time does the party start? B: I think around eight. 1PP summons 2PP reply A: Excuse me B: Yes? * ((phone rings)) B: Hello:?* *Note that “Hello” at the beginning of a telephone call is not a 1PP greeting, but a 2PP reply to the ringing of the telephone. This can be made clear in dialogues of telephone calls by including ((ring, ring)) in the preceding line (Wong, 2002).

- 32. 1PP offer/invitation 2PP acceptance 2PP declination A: Wanna lift?= B: =You saved my life. A: Have a cigarette. (0.3) B: um...I don't smoke thanks. 1PP request 2PP grant 2PP refusal A: Can I borrow your car?= B: =Sure. A: Can I borrow your car? (0.4) B: Well...I dunno…

- 33. 1PP assessment 2PP agreement 2PP disagreement A: Isn’t he cute B: O::h he::s a::DORable!* A: This is interesting! B: Yeah, really interesting!* *This type of agreement is called “upgrade” (see Pomerantz 1984 A: This is GREAT! B: Yeah, it’s ok** **This type of “downgrade” agreement regularly foreshadows upcoming disagreement. *** Also note that "I agree" and "I think so too," which are both taught in EFL texts, are heard as "same assessments" which also regularly prefigure disagreement.

- 34. Discussion In the following example, B orients to A's prior turn as an accusation and issues a denial. What made A's turn hearable (to B) as an accusation? A: You left the lights on. B: It wasn't me. Again B orients to A's turn as an accusation, but this time offers an apology. What made A's turn hearable (to B) as an accusation? A: It's half past six. B: Sorry (we had an unexpected meeting) Note: In doing CA it is not up to the analyst to decide what a given turn-at- talk is doing. What matters is how participants orient to that talk.

- 35. 1PP accusation 2PP denial 2PP apology A: You left the lights on. B: It wasn't me. A: It's half past six. B: Sorry (we had an unexpected meeting) 1PP apology 2PP minimalization A: Please excuse Dan B: It’s nothing Many of these adjacency pairs seem to be "universal" in the sense that it's hard to imagine a culture in which a greeting wouldn't make relevant a greeting or a request wouldn't make relevant either granting or denying. However, the resources and manner for doing these actions may vary significantly from language to language and culture to culture.

- 36. Complaint sequence (Dersley & Wootton, 2000)

- 37. 1PP compliment 2PP minimalization 2PP denial 2PP acceptance 2PP return compliment A: This is delicious. You’re really a great cook! B: My mother did most of the cooking. A: You're a wonderful cook! B: No, no, no, I'm useless in the kitchen! A: You're a wonderful cook! B: Thank you. A: You're a wonderful cook! B: So are you. Unfortunately much that has been written about adjacency pairs in the pragmatics and TESOL literature is distorted or misleading. They have sometimes been mischaracterized as conversational “boilerplate” or “fixed routines” or “conversational gambits.”

- 38. Adjacency pair expansion* A base adjacency pair can be expanding in three locations: Pre-expansion, insert-expansion, and post-expansion. Each of these expansions is a sequence in its own right and there can be multiple expansions in each position. Schegloff (1990) analyzes one single action sequence, which extends for over 100 lines of the transcript, which turns out to be structured around one single adjacency pair, namely, a request and its eventual granting. *Schegloff (2007) spends almost 150 pages (p.22-168) on the the nuts and bolts of sequence expansion. Sadly, I can only provide a minimal overview here.

- 39. Pre-expansion The use of one or more pre-expansion sequences is done to check on the likelihood that a possibly upcoming action will receive a preferred response. If not, the base adjacency pair may not happen at all. "…we should appreciated that pre-sequences or pre-expansion are measures undertaken by the speaker – or the prospective speaker – of a base first pair part to maximize the occurrence of a sequence with a preferred second pair part." (Schegloff, 2007:81) In terms of distribution, we empirically find more acceptances, grantings, and agreements, not because people want to do these actions more frequently, but precisely because considerable interactional work has been done to avoid getting a dispreferred response. Three common types of pre-sequences are pre-invitations, pre-requests, and pre-announcements.

- 40. Not "pre" as in "before" but "pre" as in preliminary to.

- 41. Pre-invitations Go-aheads In the following examples a pre-invitation gets a go-ahead response that acknowledges the possibility of an implied upcoming invitation. A go-ahead is a preferred next action. In doing a go-ahead, speaker B indicates a positive disposition towards a possible invitation. A: Are you busy on Friday? B: No, not really. (Not at all, No, I’m just…) GO-AHEAD A: What are you doing around 8pm? B: Nothing much. GO-AHEAD A: Do you like Irish music? B: Yeah, I love it! GO-AHEAD

- 42. Pre-invitations Blocks Conversely, speaker B may choose to block the potential invitation which may result in the invitation not being done at all or being approached in an alternative, less direct, format, e.g. “I heard there’s going to be live Irish music on Friday and I was thinking of checking it out.” If speaker B displays interest upon hearing this, an invitation to “join me” might then be forthcoming. A blocking move is a dispreferred action and is often packaged using the dispreferred turn shape. A: Are you busy on Friday? (…) B: Um…I’ve got some stuff I sort of have to do. BLOCK A: Do you like Irish music? (…) B: iyeah…not so much. BLOCK *Note: English learners regularly fail to hear these sorts of turns as pre- invitations and instead orient to them as “questions,” to which they regularly provide an “answer,” which might be taken as a blocking move.

- 43. Pre-invitations Hedges Another type of possible response to a pre-invitation is to adopt a tentative orientation towards a possible upcoming invitation suggesting that possible acceptance is contingent on the specifics of the invitation. A: Are you busy on Friday? (…) B: Just doing some odds and ends, why? Following a hedged response the producer of the pre-invitation might instead take the safer route of mentioning plans, safer in the sense that "talk about plans" isn't subject to "rejection." If these plans are enthusiastically received, an invitation may follow. A: Are you busy on Friday? B: Not particularly, why? A: A couple of us are thinking of having a BBQ at the beach… B: That sounds like a lot of fun! A: We'd love to have you join us.

- 44. Pre-offers Go ahead / Block Offers are similar to invitations. In fact, Schegloff (2007:35) suggests that invitations may be seen as a sub-class of offers. As such we also find pre-offers, which seek to see if the offer will be welcome. Cat: I'm gonna buy a thermometer though [because I= Les: [But- Cat: =think she's [(got a temperature). Les: [We have a thermometer. Cat: (Yih do?) Les: Wanta use it? Cat: Yeah. Pet: I'll see you Tuesday. Mar: Right. Pet: O[k a y Marcus ] Mar: [You- you're al]right [you can get there. Pet: [Ye- Pet: Yeah Mar: Okay ((<<- No offer is forthcoming))

- 45. Pre-requests: Go-aheads and blocking moves Like invitations, requests are often prefaced with one or more pre- request sequences. Again the pre-request seeks to check on the likelihood of a preference response: granting. Common types of pre-requests are “Are you free…” “Do you have…” “Do you know how to…” and so on. Even many seemingly “neutral” questions might actually be heard as possible pre-requests, e.g. “Are you going into town this afternoon?” "Have you ever fixed a computer?" Again, the pre-request can receive a go-ahead or a block. A: Do you have a hammer? B: Sure. A: Do you have a hammer? (…) B: iyeah, but…I’m not sure where it is at the moment.

- 46. Pre-announcements (or pre-telling) This type of sequence is used with news announcements (i.e. "telling news") both to check whether the news is really new (to this participant) and for co-participants to display their acceptance of the role of news- recipient, sometimes even when subsequent talk reveals that they do, in fact, already know the news. A: Guess what. B: What. A: Guess how much I paid for this? B: How much. A: Did you hear what happened at work yesterday? B: No, what. A: Hey, I got sump'n thet's wild. (We got good/bad news) B: What.

- 47. Pre-announcements Blocking / Preempting An possible announcement might be blocked by the recipient displaying that the news isn't news. A: Did you hear what happened last night? B: Yeah, shocking isn't it.

- 48. Is that a question or a pre-announcement? Below is a classic, and particularly interesting, instance of how participants might orient to a pre-announcement. It's also an illustration of what conversation analysts call the "next turn proof procedure." In line 2, Russ orients to Mother's prior turn as a pre-announcement, accepting the role of news-recipient. However, in line 3 Mother rejects this understanding and makes it clear that she meant her turn as an actual question. In lines 4-7 Russ shows that he, in fact, already has a very good idea regarding who will be at the meeting and that this really wouldn't have been "news" to him at all. 01 Mother: Do you know who’s going to that meeting? 02 -> Russ: Who. 03 -> Mother: I don’t kno:w 04 Russ: Oh::, Prob’ly Missiz McOwen (‘n detsa) en prob’ly= 05 =Missiz Cadry and some of the teachers 06 (0.4) 07 Russ: And the counsellers

- 49. Pre-pre or action projections Another type of pre-sequence is the pre-pre so named because it often precedes other pre-sequences (Schelgoff, 2007:47). Common pre-pres are “Could you do me a favor?” “Can I ask you a question?” or formulations with "Let me…" In many cases the projected action (e.g. the favor or the question) is not done in the next turn…or ultimately at all. A: Could you do me a favor? B: Sure. A: Well, you know that I’ve been having problems with my car, like the engine not starting. Well, it happened again this morning and I’ve got this really important meeting to get to this afternoon, but the garage guy says the car isn’t going to be ready until maybe the day after tomorrow… This extended turn seems aimed at getting B to making a pre-emptive offer of assistance. Requests are unusual in that they are a dispreferred first pair part. Another type of interactional work that a pre-pre can do is to mark some upcoming favor or question as “delicate.”

- 50. Practicing a pre-pre sequence A: Could you do me a favor? B: Sure. A: [EXTENDED TELLING SEEKING PREEMPTIVE OFFER] B: Preemptive offer ..

- 51. Insert-expansion Quite often the talk that occurs in the next turn after a first-pair part is hearably not a second-pair part. For example, a request might be followed by a question asking for more details. (pre-second) A: How long does it take to get there? 1PP B: Are you going by car? 1PP A: Yeah. 2PP B: About 40 minutes. 2PP However, insert-expansion can be heard as implicative of an upcoming dispreferred action. This follows the general principle that anything that occurs in the location where a preferred action should have occurred (i.e. immediately) displays possible disaffiliation. (post-first) A: Do you want to have Thai food for dinner? B: What? REPAIR A: Would you rather have something else?

- 52. Insert-expansion (post-first vs. pre-second) "Whereas post-first inserts look backward, ostensibly to clarity the talk of the first pair part, pre-second inserts look forward." Schegloff, 2007:106) Consider the insert expansions in this 911 call. A: Send an emergency to fourteen forty-eight Lillian Lane. 1PP B: Alright sir. We'll have them out there. 2PP Cal: 1PP Send 'n emergency to fourteen forty eight Lillian Lane. Pol: PF Fourteen forty eight – [What sir? Cal: [yesh. Pol: PF Li[llian Lane? Cal: [Fourteen forty eight Lillian. Pol: PF Lillian. Cal: Yeah. Pol: PS What's th' trouble sir. Cal: Well. I had the police out here once, Now my wife's got cut. Pol: 2PP Alright sir. We'll have 'em out there. Cal: Right away? Pol: Alright sir.

- 53. Post-expansion In adjacency pairs which receive a preferred second pair part, such as accepting, granting, agreeing, the sequence typically ends and the talk moves on, or the post-expansion is minimal. A: Could I borrow your camera? B: Sure, no problem. A: Thanks. ( sequence closing third) However, in the case of a dispreferred response, the sequence may be re-opened in pursuit of the preferred response.* A: Could I borrow your camera? (…) B: Um…I dunno…I sort of hate to lend it out to anyone… A: I'll take good care of it and get it back to you tomorrow right. *Schegloff (2007) provides a full discussion of the many subtle aspects and specific practices involved in post-expansion.

- 54. Why sequence organization matters “…a great deal of talk-in-interaction – perhaps most of it – is better examined with respect to action than with respect to topicality, more for what it is doing that for what it is about.” (Schegloff, 2007:1) The primary context for understanding what is being said and done in the current turn-at-talk is what was said and done in prior turns, often the just prior turn. Recognizing the type of sequence that is underway is of crucial importance to producing a relevant next turn-at-talk. Sequence organization lies at the core of a “grammar for interaction.” Sequence organization has been almost wholly ignored in ESL/EFL teaching materials. The structure of sequences is intertwined with preference organization, which is a primary resource for managing human sociality.

- 55. Expand the sequence Re-imagine the following base pair (invite – accept/reject) with one or more pre-expansions before K's turn, one or more insert expansions after K's turn, and one or more post expansions after M's turn. 1PP: Invite 2PP: Accept or Reject. Feel free to include silences, delay, and other hedges where you feel they might have occurred.

- 57. Talk-in-interaction syllabus (Part 1) I. Opening a conversation a. Face-to-face b. One the phone 1. Summons-reply 2. Greetings AP 3. "Howareya" sequences 4. Stating the reason for the call (or proposing a first topic) II. Closing a conversation a. Pre-closing moves 1. "Well, I've got to be going now." 2. "Well, it's been nice talking with you." 3. Making plans for the future ("see ya tomorrow in class") b. Closing

- 58. Talk-in-interaction syllabus (Part 2) III. invitation/offer sequences a. Making simple invitations b. Accepting an invitation using a "preferred turn shape" c. Rejecting an invitation using a "dispreferred turn shape" d. Using pre-invitations to avoid rejections 1. Go-ahead" moves following pre-invitations 2. Blocking" moves following pre-invitations 3. Responding to blocking moves IV. Request sequences a. Making simple requests b. Granting a request using a "preferred turn shape" c. Refusing a request using a "dispreferred turn shape" d. Using pre-requests to avoid refusals 1. Go-ahead moves following pre-requests 2. Preemptive offers following pre-requests 3. Blocking moves following pre-requests

- 59. Talk-in-interaction syllabus (Part 3) V. Assessment sequences a. Making simple assessments ("This's great!" “What a terrible movie.”) b. Agreeing with assessments (preferred turn shape) 1. Upgrade assessments 2. Same evaluations c. Disagreeing with assessments (dispreferred turn shape) 1. "weak agreements" + "weak disagreement" ("Yeah, it was but...") 2. Downgrade assessments (“fantastic” “OK”) d. Using "tag questions" in assessments to solicit participation e. Compliments (a special type of assessment) 1. Acceptance (Note: “Thank you” is a sequence closing third!) 2. Denial 3. Minimalization

- 60. Talk-in-interaction syllabus (Part 4) VI. Telling news a. Using pre-announcements ("Guess what?") b. Responding to pre-announcements c. Telling news d. Responding to news 1. Oh + assessment 2. Really? (prompting further news-telling) e. Using “How’s is going” as topic solicitation 1. OK/fine/good = no news to tell 2. Great!/Terrible! = news to tell

- 62. “Do you teach grammar?”

- 63. "Grammar, of course, is the model of closely ordered, routinely observable social activities." (Sacks, 1992:31[Fall 1964, lecture 4])

- 64. Preference organization There is a form of social organization, a grammar of sorts, which shapes many aspects of talk-in-interaction. Conversation analysts call it preference organization. It intersects with the concept of "face" but goes further by specifying the practices involve. Lerner, G. (1996). Finding "face" in the preference structures of talk-in- interaction. Social Psychology Quarterly, December. The organization of preference(s) affects how we tailor our talk for particular recipients (recipient design). It influences how we describe persons, places, and events, how we construct invitations as well as how we respond to them, how requests are designed and how we shape the responses, how we agree and disagree, how we ask questions and how we answer them…and much more. In short, it cuts across many of the bread-and-butter areas of language instruction. Yet it is either entirely absent from language teaching materials or only accidentally found usually in distorted form.

- 65. CA preference ≠ Personal preference The concept of preference in CA is not about "preferring" this or that in the everyday sense. It's not about "likes" and "dislikes" as in "I prefer dogs to cats." It is not a personal or psychological preference. It is a shared social preference grounded in observable practices. Preference refers to a systematic (structural) and asymmetrical relationship between alterative descriptions or actions. It is deeply rooted in the norms, and reflected in the practices, of social interaction. The CA terms preferred and dispreferred are somewhat similar to unmarked vs. marked in linguistics. Broadly stated, preferred actions reflect a no-problem orientation, while dispreferred actions suggest a problematic stance. In question formation, turns can be formatted such that they "build-in" a bias towards a certain type of response. More on that tomorrow!

- 66. Preference for persons, places, and events Some of the earliest considerations into what came to be called preference emerged from the general principle of recipient design. "If possible, select a description that you know the other knows." (Sacks, 1992: II:148) In terms of person reference, there is an observed preference for a recognitional ("John") vs. non-recognitional reference ("this guy I know"). An answer to the question "where do you live" may be selected from among an open set of possible responses, including: the US, California, Orange County, Orange, close to Disneyland, about a hour outside of LA, just across the street from Sally, etc. Events, to which one may be invited, can also be characterized in multiple ways (dinner, drinks, coffee, watch a game, hang out, etc.). Drew (1992, expanding on Sacks' earlier discussion of this in his lectures) argued that these descriptions are ordered along what he called the principle of "maximal property of descriptions."

- 67. Preference in adjacency pair organization In the case of a 1PP greeting, a 1PP summons, or a 1PP question, there is only one relevant 2PP. Other 1PPs, such as invitations, offers, requests, assessments, compliments, etc. have two or more relevant 2PPs. For example, an invitation makes relevant either an acceptance or a rejection. Yet, these alternative actions are not symmetrical. They are not treated equally by participants. One of these relevant actions is oriented to as systematically preferred, i.e. as the preferred next action. The other is a dispreferred next action and this orientation is displayed ("marked") via a set of interactional practices. In the case of an invitation, acceptance is the preferred next action and rejection is the dispreferred next action. Once again, we are not talking about personal preference. You may strongly wish to reject the invitation, but you will still structure your rejection along the lines laid out by preference organization.

- 68. Preferred turn shape Preferred next actions are regularly formatted ("packaged") in characteristic ways (see Sacks, 1987; Pomerantz, 1984; Schegloff, 2007; Pomerantz and Heritage, 2013). This is most immediately seen in the observed fact that the preferred action is typically done a soon as possible. This orientation manifests itself in two ways: 1) Next speaker begins speaking with little or NO GAP and 2) the preferred action is done as early as possibly in the turn. A: Do you want to go to a movie? B: Sure, sounds fun. (Acceptance coupled with positive assessment)* In this example, there is no gap whatsoever between the end of "movie" and the onset of "sure." (Note that there is also no hesitation in the production of "sure" as there is in "s:::ur::e) This single word, placed precisely where it is, does the work of accepting the invitation. *Compare with the stilted “yes, I do” short-answer format.

- 69. The importance of timing 1) Counting in circles 2) Do you want to play tennis? Sure.

- 70. Dispreferred turn shape In contrast, dispreferred next actions (e.g. rejecting, refusing, disagreeing, and in general disaffiliating) are regularly packaged using a well-documented…and teachable…set of practices. These practices can be broadly described as delaying the doing of the dispreferred action, and thereby providing warning. As opposed to the "on-time" start of preferred actions, dispreferred actions are regularly preceded by a silence. Even a micro-silence can suggest an upcoming dispreferred response, if it is noticeable to participants. Dispreferred turns (and the dispreferred sequences that often turn into) typically include pauses, hesitation tokens (um, er, well, I dunno), hedges (sort of, kind of, a bit, etc.) repetitions, excuses, questions, and/or apologies. In many cases, they entirely avoid “saying no” (see Carroll, 2011a).

- 72. Dispreferred turn shape In the following example, a rejection gets postponed using a range of practices, which both delay the dispreferred action within the turn as well as push it “downward” within the sequence. When the dispreferred action finally does appear, it is as the very last word (and the very last resort) in the turn and the sequence. Ideally it would not have occurred at all, if the inviter had backed down, for example, by saying "Well, maybe some other time." A: Would you like to go to a movie? (0.2) B: Um::..iyeah…I dunno…a movie? A: Uh-HUH. (0.3) B: .hhh when? A: On Saturday. B: Iyeah…I dunno...I sorta gotta do some stuff… so…um...I guess not.

- 74. Reacting to warnings Quite often foreshadowing a possible upcoming (though not yet produced) dispreferred action is enough to cause the prior speaker to backdown or modify what was said. B: . . . An' that's not an awful lotta frutcake (1.0) B: Course it is. A little bit goes a long way. A: Well that's right In the following example, Gene responds to the potential problem (as displayed by Mary) by proposing a candidate reason himself ( i.e. you're not available because you're working nights). Gene: Whenih you uh: what nights'r you available. (0.4) Mary: .k.hhhhh[hh Gene: [Are you workin' nights et all'r anything? Mary: I do: I work, hhh a number o:f nights Gene. . .

- 75. Dispreferred sequences Note that not only are there dispreferred next actions, there are also dispreferred sequences. Schegloff (2007:82) identifies (at least) three types of preference in sequences: 1)There appears to be a preference for offer sequences over request sequences. 2)There appears to be a preference for noticing by others over announcement-by-self. 3)There appears to be a preference for a party to be recognized (if possible or relevant) over self-identification. Participants often work to avoid doing a request at all, for example, by telling trouble instead of formulating a request, which regularly occasions a pre-emptive offer of assistance (see Carroll, 2012 for how this might be taught). If a request is made (and the speaker feels lower entitlement), it may be formatted using the characteristic shape of dispreferred turns.

- 76. Observations on requests (Schegloff, 2007:83) 1)Requests appear disproportionately to occur late in conversations…and seem especially problematic and unlikely to occur in first topic position. 2)Requests are regularly accompanied by accounts, mitigations, candidate "excuses" for the recipient, etc. which are done in advance of the request itself… 3)As with other "sensitive" or "delicate" conversational practices or actions, the occurrence of one may "license" the occurrence of others. 4)One evidence of the treatment of requests as dispreferred is the masking of them as other actions, often as ostensible offers… 5)The preferred response to a pre-request is not a go-ahead; this simply forwards the sequence to a first part part – a request – which is the less preferred way of implementing the project at hand. . . The preferred response…is to pre-empt the need for a request altogether by offering that which is to be requested.

- 77. Preference and adjacency pair expansion An orientation to preference organization often lies behind the sort of AP expansions that we looked at in the last session. Pre-expansions, (pre- sequences) are aimed at securing a preferred response. "…we should appreciate that pre-sequences or pre-expansion are measures undertaken by the speaker – or the prospective speaker – of a base first pair part to maximize the occurrence of a sequence with a preferred second pair part." (Schegloff, 2007:81) Insert expansion, in the form of repair (in particular "other-initiated" repair), regularly foreshadows a dispreferred action, such as the rejection of an invitation or refusal of a request. Post-expansion seeks to keep an AP going after the provision of a 2PP particularly when that 2PP is a dispreferred action. In other words, post- expansion can "pursue" a preferred 2PP.

- 78. Preference organization: Agreeing and disagreeing

- 79. Assessments and second assessments Pomerantz (1984) examined assessments in conversation. Her findings are worth summarizing here. As an initial observation, Pomerantz noticed that assessments (“opinions”) are regularly followed by second assessments as in the following instances (ibid.:59-61). This may seem obvious, but EFL learners are frequently stumped for a response when presented with an assessment. J T’s- tsuh beautiful day out isn’t it? L Yeh it’s jus’ gorgeous... J: It’s really a clear lake, isn’t it? R: It’s wonderful B: Isn’t he cute A: O::h he::s a::DORable C: ...She was a nice lady--I liked her G: I liked her too

- 80. “In general, dispreferred-action turn organization serves as a resource to avoid or reduce the occurrences of overly stated instances of an action. The preference structure that has just been discussed - agreement preferred, disagreement dispreferred - is the one in effect and operative for the vast majority of assessment pairs. Put another way, across different situations, conversants orient to agreeing with one another as comfortable, supportive, reinforcing, perhaps as being sociable and as showing they are like-minded… …likewise, across a variety of situations conversants orient to their disagreeing with one another as uncomfortable, unpleasant, difficult, risking threat, insult, or offense.” Pomerantz (1984:77)

- 81. Agreeing or disagreeing The second assessment can either agree or disagree with the first assessment. In most (but not all) situations agreement is the preferred next action and disagreement is the dispreferred next action. Pomerantz also noticed that preferred next action turns shared common characteristics. For example, they are frequently produced immediately after the 1PP assessment. Also these turns are typically fairly short and direct. Disagreeing turns also shared common characteristics. They are typically delayed and longer (or involve more turns) and regularly include pauses, questioning repetitions, requests for clarification, repair initiators (e.g. “What?”, “Huh?”), etc. As Pomerantz (1984:70) states: “A substantial number of such disagreements are produced with stated disagreement components delayed or withheld from early positioning within turns and sequences.”

- 82. Three types of agreeing assessments Pomerantz identified three main types of “agreeing” second assessments in her data: 1) upgrades **************************** 2) same evaluations 3) downgrades While all three are presented as agreement, Pomerantz found that same evaluations and downgrades often prefaced actual disagreement and therefore should be considered “weak agreement” forms, which foreshadow possible disagreement.

- 83. 1) upgraded assessments (upgrades) Upgrades are uttered or worded in a way that is stronger than the first assessment and, as such, display strong agreement. a) The second assessment uses a stronger evaluative term. A: Isn’t he cute B: O::h he::s a::DORable J: T’s- tsuh beautiful day out isn’t it? L: Yeh it’s just gorgeous... b) An intensifier is used (very, really, extremely, awfully…). M: You must admit it was fun the night we= =went [down J: [it was great fun... B: She seems like a nice little [lady A: [awfully nice little= =person

- 85. Upgrade activity #2 Itsy-bitsy, teeny-weenie Itsy-bitsy Teeny Tiny small

- 86. 2) same evaluations With same evaluations, the second assessment typically matches the intensity of the first assessment. C: ...She was a nice lady — I liked her G: I liked her too A: He’s terrific B: He is. Same evaluation can regularly be found in agreement turns, but they also frequently preface disagreement and should therefore be considered weak agreements. J: Oh it’s [terribly depressing. L: [oh it’s depressing. same evaluation E: Ve[ry L: [but it’s a fantastic film. disagreeing *EFL learners are taught “I agree” and “I think so too.” which are same evaluations, thus, displaying weak agreement suggesting disagreement.

- 87. 3) downgraded assessments (downgrades) With downgrades the speaker chooses a weaker wording. Downgrades should also be considered “weak agreement” and, therefore, as foreshadowing possible upcoming disagreement. A: She’s a fox! B: Yeh, she’s a pretty girl. F: That’s beautiful K: Isn it pretty Downgrades frequently result in subsequent rebuttal as in the following excerpt where a first assessment is offered (“a fox”), which receives a downgraded evaluation (“a pretty girl”). This then causes the prior speaker to reassert his position with an even stronger term (“gorgeous”). A: She’s a fox. L: Yeh, sh’e a pretty girl. A: Oh, she’s gorgeous!

- 88. Basic patterns for disagreement Pomerantz also identified two basic patterns for disagreement (when disagreement is a dispreferred action). Pattern 1) tokens/delays + strong disagreement R: ...well never mind. It’s not important. D: Well, it is important. Pattern 2) tokens/delays + weak agreement + weak disagreement R: Butchu admit he is having fun and you think it’s= =funny. K: I think it’s funny, yeah. But it’s a ridiculous= =funny.

- 89. The impact of unstated disagreements A silence after an assessment can be heard as a sign of potential future disagreement. As a result prior speaker may choose to continue (Rule 1c) with something designed to deal with this potential disagreement even before it occurs as in the following case where B states an opinion, then backs down from the original assessment. B: ...an’ that’s not an awful lotta fruitcake. (1.0) ` B: Course it IS. A little piece goes a long way.

- 90. Disagreement as preferred next action While agreement is a “preferred action” in most situations, it is not the preferred action in all situations. One situation where it is not the preferred action is after a “self-deprecating” assessment, i.e. when the prior speaker has said something negative about him/herself. Pomerantz (1984:81) states: “If criticizing a co-conversant is viewed as impolite, hurtful, or wrong (as a dispreferred action), a conversant may hesitate, hedge, or even minimally disagree rather than agree with the criticism.” B: ...I’m tryina get slim. A: Ye:ah? [You get slim? B: [heh heh heh heh hh hh A: You don’t need to get any slimmah, A: ...I’m so dumb I don’t even know it hhh! — heh! B: Y-no, y-you’re not du:mb,... These disagreements are packaged in the preferred turn shape. .

- 91. Conflicting ("cross-cutting") preferences There can be situations in which multiple preferences are at work. For example, there is a preference for agreeing with assessments. However, doing self-praise is dispreferred. So how are participants supposed to deal with compliments (which come packaged as assessments)? Pomerantz (1978) demonstrates that it is the constraints imposed by these cross-cutting preferences that account for the manner in which most compliment responses are designed. In the following examples, the compliment is downgraded or minimalized, but not outright rejected. A: Oh, it was just beautiful. B: Well thank you Uh I thought it was quite nice. A: Good shot B: Not very solid though A: You're a good rower, Honey. J: These are very easy to row. Very light.

- 92. Why preference organization matters “Preference principles play a part in the selection and interpretation of referring expressions, repair, turn-taking, and the progression through a sequence of actions. In addition, there are contexts in which participants orient to multiple preference principles. Sometimes, these multiple principles are in conflicts with one another, and, in those circumstances, participants use systematic practices to manage the conflicts involved.” (Pomerantz and Heritage, 2013:210) Preference organization is fundamental to the structure of talk-in- interaction and to navigating our social worlds. Preference organization has implication for the design of both questions and their replies. Guiding learners towards an understanding of the practices proficient English speakers use to handle both preferred and dispreferred actions will help them interact with fewer social problems.

- 93. Why preference organization matters Research on preference organization demonstrates how inappropriate, or just plain grammatically wrong, the so-called “short answers” common to virtually every EFL textbook are, e.g. A: Do you want to go to a movie? B: No, I don’t. This is “structurally incorrect” because a dispreferred action has been packaged using the preferred turn shape. As a result teachers and textbooks are actually teaching students how to act “curt” and “hostile.” It is vital that learners know how to reject as well as accept, how to refuse as well as grant, how to disagree as well as agree. EFL materials generally do a poor job of this. Quite often textbooks present an eternally rosy world where everyone accepts, grants, and agrees. Or the examples of doing rejecting, refusing, disagreeing, etc. do not reflect observations from naturally occurring talk-in-interaction.

- 94. Why preference organization matters Research on preference organization demonstrates how inappropriate, or just plain grammatically wrong, the so-called “short answers” common to virtually every EFL textbook are, e.g. A: Do you want to go to a movie? B: No, I don’t. This is “structurally incorrect” because a dispreferred action has been packaged using the preferred turn shape. As a result teachers and textbooks are actually teaching students how to act “curt” and “hostile.” It is vital that learners know how to reject as well as accept, how to refuse as well as grant, how to disagree as well as agree. EFL materials generally do a poor job of this. Quite often textbooks present an eternally rosy world where everyone accepts, grants, and agrees. Or the examples of doing rejecting, refusing, disagreeing, etc. do not reflect observations from naturally occurring talk-in-interaction.

- 95. Challenges facing future study of preference Pomerantz and Heritage (2013) argue that one current weakness in research on preference is an overly simplistic association of one preference with overly broad action categories, for example stating that "accepting invitations/offers is preferred" or that "requests are dispreferred." Not all invitations are alike. Not all requests are alike. "Would you like the last piece of pie?" (Clearly prefers rejection) Likewise, whether a given request is designed and oriented to as preferred or dispreferred appears to hinge on what participants perceive (and display to co-participants) as the level of entitlement. Requests reflecting strong claims to entitlement may take the form of imperatives ("Pass the salt") while requests suggesting lower entitlement (higher contingency) may receive different treatment. As such, future research into preference will need to look deeper and at a more situated level. For language teachers this means that we need to be carefully about being overly dogmatic in our presentation of preference organization.

- 96. Preference in question design Today we have addressed some of the ways that preference plays out in sequential organization. For the most part, this dealt with preference related to a 2PP. However, it has long been known both in linguistics and conversation analysis that preference organization is often implicit in the design of questions (and questions as vehicles for other social actions), that the formatting of a question can embed a preference for the type of response it seeks to engender (see Bolinger, 1978; Heritage, 1984; Heritage, 2002; Heritage, 2003; Heritage, 2010; Lee, 2013; Pomerantz, 1984, Pomerantz and Heritage, 2013; Sacks, 1987). Furthermore, the replies to questions themselves reveal an orientation to these embedded preferences. But that's a topic for another day…specifically tomorrow!!!

- 97. What is the CA attitude towards grammar?

- 98. "Grammar, of course, is the model of closely ordered, routinely observable social activities." (Sacks, 1992:31)

- 99. "…it should hardly surprise us if some of the most fundamental features of natural language are shaped in accordance with their home environment in co-present interaction, as adaptations to it, or as part of its very warp and weft. For example, if the basic natural environment for sentences is in turns-at-talk in conversation, we should take seriously the possibility that aspects of their structure - for example - their grammatical structure - are to be understood as adaptations to that environment." (Schegloff, 1996:54)

- 100. Did the canyon make the river?

- 101. Or did the river make the canyon?

- 102. More than just grammar… Experience with CA has led me, as a language teacher, to re-evaluate almost everything I thought I knew about "grammar." What we need is grammar-in-interaction and grammar-for-interaction, which extends beyond the traditional borders of syntax. Research in the field of CA is helping to build this grammar-for-interaction one empirical observation at a time.

- 103. CA insights on teaching conversation The reason to teach conversation is not to practice the linguistic system, but because it is the most ubiquitous form of human interaction and the cradle of language development. Talk-in-interaction is a skill in its own right not to be subsumed under “speaking.” Recognize that mundane conversation is the baseline, and most complex, form of talk-in-interaction. Design activities that promote this type of conversation. Discussion, and in particular academic discussion, is a specialized genre that should not be confused with conversation, although many of the practices are shared.

- 104. CA insights on teaching conversation Most talk is organized around action sequences rather than topics. Therefore, conversation textbooks should not have units themed around topics. Units are better organized around action sequences and their expansions and alternative trajectories. Sample conversations (authentic, simplified authentic, or scripted) should ensure that natural turn-taking practices are accurately reflected. For example, even in 2-party talk, the sequence of speakers is not necessarily A > B > A > B. More open-ended tasks allow for more natural interaction. Shift focus away from the “structures of language” to the “structures of practice” (Lerner, 1996). In other words, focus on how participants manage talk-in-interaction.

- 105. CA insights on teaching conversation Move away from typical textbook “information gap” activities which rarely result in authentic interaction. Minimize the use of traditional EFL dialogues, particular ones designed to present a specific grammatical feature. If possible use authentic or modified authentic examples and/or scripted examples, which conform to empirical observations, for example about the shape of dispreferred turns. Many sequences can be presented in as few as two to four turns. We might call these mini-logs. Any full dialogue will almost certainly never be heard again. However, these mini-logs and the language in them are often high frequency. CA-inspired teaching materials should be designed in a way that teachers with little or no knowledge of CA can still use the materials. It is not advisable to explicitly use CA terminology with learners. The teacher’s manual can help prepare the teachers.

- 106. Questioning Questions: Questions and their Replies as Social Actions

- 107. Traditional EFL approaches to teaching questions and answers

- 108. Questions, questions, questions English language textbooks and teachers spend an inordinate amount of time teaching the syntax of English questions and answers. Textbooks almost always group questions according to their grammatical form. First, there are the yes/no ("polar") questions using the present tense forms of BE. In this unit, students usually also get their first taste of the so-called "short-answer" format replies. Next up are polar questions with present tense forms of DO. Sometime later they get the past tense forms (was, were, did). Then come questions using the "present perfect" (a label which communicates exactly nothing). These are followed by the Wh-questions with these auxiliaries. EFL textbooks are all about the GRAMMAR of questions. Little or no thought is given to the communicative or socio-interactive functioning of questions.

- 109. How do you teach questions?

- 110. If you are like most EFL teachers around the world… …you have probably, without thinking much about it, been teaching questions through transformation.

- 111. Transformational grammar lives on…and on… A great many EFL teachers have never heard of Noam Chomsky or his Transformational Generative grammar. Yet a great many of these teachers and a great many EFL textbooks teach questions through transformation…as if doing algebra! That is to say, students are presented with a statement and required to transform it into a question. He is a doctor. Is he a doctor? She works in a bank. Does she work in a bank? This is essentially having the students turn an answer into a question, which is certainly the wrong way around.

- 112. English question formats and functions A better approach is to teach students (i.e. "lead learners to learn") how to match the intent of their question with the appropriate format. INTENT FORM ? ABOUT HABIT Do you… ? ABOUT SPECIFIC PAST ACTION Did you… ? ABOUT EXPERIENCE (EVER) Have you…(ever)… ? ABOUT EXPERIENCE (ALREADY) Have you…(already)… ? ABOUT ABILITY Can you… ? ABOUT CURRENT ACTIVITY Are you V+ing… ? ABOUT INFORMAL FUTURE Are you going to… ? ABOUT FUTURE PLAN Will you… ? ABOUT OBLIGATION Do you have to / need to… ? A=B? Are you…

- 113. Grammar formation of Information questions In English, the so-called Wh-questions are formed by combining interrogative words with one of the forms of either an auxiliary verbs DO, BE, HAVE or one of the modal verbs. What… Where… When… Why… Who… / Whom… Whose… Which… Which+Noun… (an unlimited number of these) How… How+Adjective… (an unlimited number of these) Again, this is usually presented from a purely mechanical perspective and often again in transformation drills of turning answers into questions, e.g. He works in a bank. Where does he work?

- 114. The EFL Grammar Mirror Most EFL teaching materials treat responses to questions as a sterile matter of grammar transformation…as a simple reflection of the grammar (and vocabulary) of the question. This is not what we normally find in naturally-occurring talk. A: Where do you live? B: I live in Tokyo. A: What is your favorite color? B: My favorite color is blue. A: Where did you go last weekend? B: Last weekend, I went to my friend's house.

- 115. Activity: Non-mirrored answers 1) Q: Who did you go with? 2) Q: How much did it cost you? 3) Q: Where do you live? 4) Q: When are you going to the party? 5) Q: Where did you go last night? 6) Q: Where are you from? 7) Q: What type of sports do you prefer? 8) Q: Where is your piano concert? 9) Q: How did you get there? A) R: Well, I grew up in southern California. B) R: Well, it’s supposed to start at nine, I think. C) R: Well, my hometown is, or was, Takamatsu. D) R: Well, we started the evening at my friend’s house, his apartment. F) R: Well, I ended up going alone. G) R: Well, I had planned to take the train but… H) R: Well, initially, it was scheduled to be held at the city hall. I) R: Well, actually, I got a huge discount. J) R: Well, I’m more into reading and watching movies.

- 116. Replies to polar questions: The short answers The format as presented in EFL textbooks begins with either a "yes" or a "no" token followed by a clause consisting of a subject (usually a pronoun or "there") plus repetition of the question's auxiliary or modal verb (mirroring the tense in the question). The polarity of the verb matches the turn-initial token, e.g. Yes, I do. / No, she wasn't. / Yes, they have. / No, he can't. / Yes, we did. / No, it won't. [yes / no] + [subject pronoun / there] + [auxiliary / modal] A: Have you been to Egypt? B: Yes, I have. / No, I haven't. A: Do you want to go to a movie? B: Yes, I do. / No, I don't. The short-answer format is DEEPLY problematic and rarely found in naturally occurring interaction…as we shall see later.

- 117. But what are questions DOING in conversation? With all this focus on the grammar of questions, EFL textbooks and syllabi seem to lose sight of the much more significant matter of what questions are actually doing in interaction. For participants there is always the interpretive issue of why some particular question, in that particular form, was done at this particular time. WHY? THAT? NOW? A: Do you want to get something to eat? B: Sure, what do you have in mind? A: I don't know. What time is it?

- 118. "…even though information (or confirmation) may be part of what a question is built to get, this seems to be virtually never…what questioning in interaction is centrally about." (Steensig and Drew, 2008:9)

- 119. Turns which assume the grammatical format of questions regularly serve as "vehicles" for other social actions.

- 120. …and not all questioning actions take the grammatical form stereotypically associated with questions.

- 121. Think of some “questions” that are primarily hearable as doing some other social action. Type them in the chat! I’ll give you a few minutes.

- 122. What social action is being being done? A: Have you ever seen such a beautiful sunset? B: __________________________ A: Would you like to come to a party? B: __________________________ A: Why weren’t you at work yesterday? B: __________________________ A: Are you an idiot? B: __________________________ A: Aren’t we going to be late? B: __________________________ A: Are you gonna eat that? B: __________________________ A: Isn’t he just the cutest thing? B: __________________________

- 125. Alternative questions (X…or Y) There are three basic question types (typologically speaking) in English: Information questions, polar questions, and alternative questions. For some reason many EFL learners seem to have a hard time with alternative questions, which they tend to answer with "yes" or "no" instead of selecting one of the alternatives. A: Would you like coffee, or tea. B: Yes. Note that sometimes the two alternatives are separated by a silence. This can be analyzed as B withholding talk at the point of first possible completion (after "coffee") resulting in silence. This may serve as a warning to A of an upcoming dispreferred action (namely rejection of the offer of coffee), which prompts A to produce an alternative offering. A: Would you like coffee? (0.2) or tea. A: Would you like coffee? (0.2) or tea? (0.2)

- 126. Tag-questions Stivers (2010) states that tag-questions were rare in her data, comprising only 6% of polar questions. Furthermore, 77% of those tag-Qs employed a simple lexical tag (e.g. "right" or "huh") rather than the more complex clausal formats taught in EFL textbooks. The tag can be produced with either final rising or final falling intonation – despite the textbook characterization of them always having rising intonation. Given that the tag is regularly produced both ways, what is the interactional difference? Tag-Q with rising final intonation He's arriving at eight, isn't he? Tag-Q with falling final intonation He's arriving at eight, isn't he.

- 127. Tag-questions You often hear that the Japanese final particle "ne" has no equivalent in English. But is this really true? Kim: (Very good.) (6.5) Mark: Not bad for free huh? (0.3) Kim: Hm mm. What interactional work is being done by the addition of "ne" or "huh" at the end of a turn? Like all questions, tag-questions don't merely ask. They are also pressed into service in pursuit of other social actions. They are subject to why-that-now inspection. What do you feel is going on in the following instance? Is it a tag-question or something else? Jess: That's kind of a lot for breakfast don't-ya think?. Mike: Nah::, I thin' iz- I think it's great.

- 128. Appendor questions Some questions are built to appear as extensions of a prior turn-at-talk. They are grammatically parasitic. These are referred to as appendor questions (Sacks, 1992:660; Schegloff, 1997). Ingrid: I know that it's just too hard b't_ Like it is too hard_ It's disrupting both of our li:ves. Zoe: ((laughing loudly about other conversation))/(1.5) Mandi: Tuh be friends, or tuh be (0.2) more than friends. Ingrid: Tuh be more than friends is disrupting both of our lives. I have never seen an EFL textbook that teaches appendor questions as a strategy for producing questions, although it would seem to be quite a simple and productive method. A: I went shopping. B: For shoes?

- 129. Questions as vehicles for social actions It turns out that a very great number of “questions” in conversation, perhaps most, serve as vehicles for other actions and it is the social action, which determines what sort of response is relevant. Some turns-at-talk (which assume the grammatical shape of questions) will be heard by participants first and foremost as invitations, other questions as requests, other questions as complaints, other questions as assessments or compliments, and still other questions as part of pre- sequences or insert sequences, and so on. As such, these first-pair part actions call for something other than an “answer.” Even a seemingly neutral question such as “When does the shop close?” might be heard by a tardy friend as a mild rebuke and elicit a response such as “Don’t worry, we have plenty of time” rather than the provision of a time. From the perspective of conversation analysts looking at data, the syntactic formatting of a turn-at-talk is of secondary importance to co- participants' displayed understanding of the action it performs.

- 130. Stivers (2010)

- 131. Questions that are not (primarily) doing questioning

- 132. Fairly obvious… (Common speech acts*)

- 133. INVITATIONS / OFFERS Do you want to… Would you like to… Do you feel like V-ing… Do you want me to…

- 134. REQUESTS Can you… Could you… Would you… Would you mind V-ing… Can I… Could I… Would you mind if I…

- 135. COMPLAINTS Why can't I… Why didn't you…

- 136. Not so obvious (Interactional practices)

- 137. PRE-INVITATIONS Are you busy… What are you doing… Are you free… Do you like… Have you…

- 138. PRE-REQUESTS Are you busy… What are you doing… Do you know how to… Have you ever… Do you have a…

- 139. PRE-ANNOUNCEMENTS Did you hear the news? Did you hear Wh-Q…? Do you know Wh-Q…? Do you wanna know Wh-Q…?

- 140. PRE-PRE Can/Could I ask you a question? Can/Could you do me a favor? Can/Could you help me?

- 141. "Question design in conversation" (Hayano, 2013)

- 142. How do turns-at-talk get heard as questions? We naively think of questions as being identifiable by their grammar and/or prosody. That's certainly how EFL textbooks present questions. However, detailed study of talk-in-interaction (in numerous languages) demonstrates that grammar and prosody are frequently not reliable as markers that a particular turn-at-talk will be heard (and responded to) as "doing questioning." At the very core of "questioning" lies a recipient-tilted epistemic asymmetry (Stivers & Rossano, 2010), which in simpler terms means that the recipient has been assumed to have fuller information. It this excerpt, the interviewer (IR) asks no question, but the talk nevertheless occasions an answer by the interviewee (IE). IR: So in a very brief word David Owen you in no way regret what you did er dispite what has (happened) in Brighton this week in the Labour Party. IE: n- In no way do I regret it. ( Repeats the wording. Why?)

- 143. How do turns-at-talk get heard as questions? This type of epistemic asymmetry can even make a "why" or "how come" interrogative unnecessary in prompting an account, as in the following except. Participant A produces a statement. However, the reason lies within B's purview and thus she "answers" (provides the reason) for a question that hasn't been asked. A: . . . Yer line's been busy. Statement / Observation B: Yeuh my fu(hh) .hh my father's wife Answer / Account called me. .hh so when she calls me::. .hh I always talk fer a long time. Cuz she c'n afford it'n I can't. Hhhh heh .ehhhhhh Once again, we see that it is epistemic asymmetry that is primarily responsible for allowing a prior turn-at-talk to be heard as doing questioning.

- 144. The epistemic gradient The term "epistemic" refers to "states of knowledge." In terms of doing questioning we can think of these states of knowledge existing on a continuum…or as a gradient, the steeper the slope, the greater the epistemic asymmetry.

- 145. Presuppositions Questions embed presuppositions. The question "where did you eat?" quite obviously presupposes both that the recipient has, in fact, already eaten and that the eating was done elsewhere. Sometimes, the presuppositions can be more subtle, objectionable, or insidious. These embedded presuppositions can present a problem: "...answerers face a choice between: (a) providing a relevant answer and accepting the presupposition(s); or (b) bringing the presuppositions to the surface of the interaction, rejecting them but not answering the question, and thus potentially being heard as "evasive." (Hayano, 2013:402) In such cases, the recipient may need to employ a range of interactional practices to navigate these troubled waters.

- 146. Preference in polar question design We've seen that preference organization plays a significant role in the formatting of 2PP actions…and sequences as a whole. We have also noted that certain 1PP can be dispreferred, such as requests. It is less obvious, however, that preference organization is often implicit in the design of questions (and questions as vehicles for other social actions), such that the formatting of a question can embed a preference for the type of response it seeks to engender (Heritage, 1984; Heritage, 2002; Heritage, 2003; Heritage, 2010; Lee, 2013; Pomerantz, 1984, Pomerantz and Heritage, 2013; Sacks, 1987). These empirical studies of naturally occurring conversational data have identified constructions that normally embed a preference for an aligning “yes” response as well as those formats preferring an aligning “no” response (see Hayano 2013:405). In more formal linguistics this phenomenon has been studied under the rubric of "polarity."

- 147. (+) PREFERRED / (-) DISPREFERRED The following formats embed a preference for a (+) positive or affiliating response, which is to say, they seek to elicit a positive response. Positively formulated straight interrogative (Have you heard from her?)** Positive statement + negative tag (You’ve heard from her, haven’t you?) Positively formulated declarative questions (You heard from her?) (-) PREFERRED / (+) DISPREFERRED In contrast, the following formats embed a preference for a (-) positive response. Negative declaratives (You haven’t / never heard from her.) Negative declarative + positive tag (You haven’t heard from her, have you?) Positive interrogative + negative polarity item (any, ever, at all, yet, etc.) Positive interrogative + negatively tilted adverbs (seriously, really, etc.) ** Are you going to eat that? ( Doesn't this prefer a "no")

- 148. Reversing polarity in search of a preferred action One demonstration of the relevance of preference in polar question design is that when a dispreferred response seems to be in the offing (as displayed, for example, by silence) the questioner (A) can reverse the polarity of the question in hopes of eliciting an affiliating response as in this example (Schegloff, 2007:71): A: D’they have a good cook there? (+ PREFERRED) (1.7) (POSSIBLE TROUBLE) A: Nothing special? (- PREFERRED) B: No, Everybody takes their turn. (PREFERRED AGREEING) Given how much time and energy is devoted to questions in EFL materials, it would be worthwhile for teachers and textbook writers to learn more about how questions are actually handled in real-world interaction. For outstanding overviews of CA research on question design see Stivers (2010) and Hayano (2013).

- 149. How to discourage questions in class How many times in class have you asked the following question…and gotten no response? Does anyone have any questions? Ironically, the negative polarity ("anyone" and "any") of this formulation embeds a preference for a negative response. You are as much as telling students that you don't want them to ask any questions! In contrast, the same basic question formatted with positive polarity embeds a preference for a positive response. Does someone have a question? Of course, such subtle variations may not be enough to override EFL student reticence to speaking up in class, but such orientations to embedded preferences have been documents in CA research, for example, in doctor-patient interactions (see Heritage et. al., 2007).

- 150. Designing requests Several CA studies have investigated alternative request formats from the perspective of entitlement, both in terms of doing requests and in having them granted. Lindström (2005) looked a Swedish data. Requests in imperative form = Entitled to have request granted Requests in question form = Not entitled to have request granted Heinemann (2006) looked a Danish request formats. Negative interrogatives (e.g. Can't you…) = Entitled Positive interrogatives (e.g. Will you please…) = Not entitled Curl and Drew (2008) looked at English requests. Can you… / Could you… = Entitled, non-contingent I wonder if… = Not entitled, contingent

- 151. . Doing questioning is much more than grammar EFL textbooks tend to present questions from an almost entirely grammatical perspective. They are taught as syntax not social actions. This does language learners a great disservice. There is still much that could be said here about how "doing questioning" is actually accomplished in situated interaction. And there is still much to be investigated. But I hope you have come away with a strong feeling that doing questioning, in all its many ways, is a fundamental skill in the management of social interaction. Next, we move on to the design of responses which like questioning is of great importance in interaction and due greater consideration that it is given in EFL materials and syllabi.

- 152. Clausal vs. phrasal responses to information questions

- 153. Phrasal vs. sentential responses Teachers often insist that students answer questions using a “full sentence,” the pedagogic purpose being to drill some grammatical structure. However, CA research (Fox and Thompson, 2010, cited from Lee, 2013) reveals that unmarked, or in CA parlance preferred (or canonical or default) responses to Wh-questions are typically packaged as lexical or phrasal units, that is to say, not as full sentences (i.e. "clauses"). These lexical or phrasal responses align with the presuppositions and relevancies of the question. In other words, they treat the question as unproblematic. In the following example of a preferred phrasal response (from Fox and Thompson, ibid.:137) note that the response is provided immediately (with no gap) upon the completion of the question as is typical of the preferred turn shape described by Pomerantz (1984). Molly: .hhh How far up the canyon are you.= Feli: =Ten miles. ( phrasal response)

- 154. Phrasal vs. sentential responses A full sentential response suggests some type of misalignment with the presuppositions of the question (Fox and Thompson, 2010). Q: Where are you from? (.) R: I live in New Zealand. ( sentential response) Contrast this with the alternative phrasal response below, which aligns seamlessly with the question. Q: Where are you from? R: New Zealand. ( phrasal response) Minor troubles can still be displayed in phrasal responses through various delays and hedges. However, sentential responses display more significant trouble, are less frequent, and often incorporate delays and prefaces. In short, lexical or phrases responses provide a “no problem” answer, while a sentential length answer suggests disaffiliation towards the presuppositions of the question.

- 155. Phrasal vs. sentential responses A full sentential response suggests some type of misalignment with the presuppositions of the question (Fox and Thompson, 2010). Q: Where are you from? (.) R: I live in New Zealand. ( sentential response) As further talk revealed, R was actually born in Pakistan, but had immigrated to New Zealand with his family as a young child. His full sentential response resists his perception of an embedded presupposition that the formulation "where are you from" is tied to ethnic identity.

- 156. Inferring purpose of a query Pomerantz (2017) examines question-answer sequences in which the reply does more than just answer the literal question (also see Walker, Drew, and Local, 2011). Instead, the response addresses the inferred reason behind the question. This practice reflects nicely the WHY…THIS…NOW challenge constantly facing the recipient of a question. Shi: hhh Suh how'r you? Ger: Oka:y d'dju just hear me pull up?= Shi: =.hhhh NO:. I wz TRYing you all day. 'n the LINE= =wz busy fer like hours. Ger: Ohh:::::::, ohh::::: Shirley's answer provides an reason as to why (from Geri's perspective as indicated by her inclusion of "just") this phone call came immediately after she returned home. A: _______________________? (One student writes a question) B: Why? A: _______________________. (Another student gives a reason)

- 157. Crafting responses to polar questions

- 158. Responses to polar questions As with information questions, a great many polar (“yes/no”) questions are actually doing something other than questioning, i.e. requesting information. This is obvious from the fact that 70% of the questions in Stivers (2010) data were built as polar questions. An inquiry such as “Do you like pizza” is rarely oriented to as a neutral question about “likes and dislikes” (as is typical in beginning units of EFL textbooks). Instead, proficient language users will more likely hear this as initiating a pre-invitation sequence, making relevant a go-ahead or a blocking move (or a hedged response). In fact, the design of responses to polar questions is much more interesting, much more varied, and much more important than the unnatural (and problematic) formats taught in EFL textbooks.

- 159. Non-answer responses A question makes relevant an answer. Not responding at all to a question, i.e. responding with silence, (as many Japanese students do) may be a socially and/or interactionally sanctionable act. Furthermore, there is a demonstrated preference in conversational data for answers over non-answer responses, which respond without actually answering (Stivers, 2010; Stivers and Robinson, 2006). Stivers (2010) found non-answer responses occurring in fewer than 20% of the hundreds of question sequences she examined. Not only are answers hugely more frequent, they are also provided much more quickly. The following except provides an instance of a dispreferred non-answer response. This follows the dispreferred turn shape, including various delays and with the non-answer (“She hasn’t said”) only provided in turn- final position. J: But the train goes. Does th’train go o:n th’boa:t? M: .h.h Ooh I’ve no idea:. She ha:sn’t sai:d.

- 160. Stand-alone "yes" or "no" responses A stand-alone “yes” response can sound curt and may shut down the sequence. Similarly, Ford (2000) showed that co-participants regularly withheld talk following a stand-alone “no” response and that this silence often prompted an expansion of the “no” response. In other words, a stand-alone “no” is treated as an insufficient response. EFL learners frequently respond with only "yes" or "no." When pressed, they tend to minimally expand their “yes” or “no” with the stock “short answer” formats…as they have been taught to do. As we saw in the section above on question design, polar questions can embed a preference for the type of response it seeks. In light of this, both “yes” and “no” can be preferred responses…or they can both be dispreferred responses. If they are preferred, the turn will usually assume the characteristic preferred turn shape. If dispreferred, then the turn (as well as sequence) may include various delays and hedges with the “yes” or “no” occurring later in the turn…or never!

- 161. Type-conforming vs. non-type-conforming Research has also demonstrated a further fundamental form of preference in responses to polar questions (Raymond, 2003; Heritage and Raymond, 2012). Raymond called responses prefaced with either “yes” or “no” tokens* type-conforming responses, in that the design of polar questions sets up an expectation for one of these two response tokens. Type-conforming responses accept the presuppositions of the question. Raymond (ibid.:948) found that type-conforming responses follow the typical design of preferred turns (see Pomerantz, 1984; Schegloff, 2007), as in the following instance from a health visitor (HV) interview with a new mother. HV: How about your breast(s) have they settled do:wn [no:w. Mom: [Yeah they ‘ave no:w yeah. *A "token" might be any variant such as "yeah" "uh-HUH" "yep" "nah."

- 162. Type-conforming vs. non-type-conforming However, Raymond also found numerous instances of non-type conforming responses, in which a response to a polar question was not prefaced by either “yes” or “no.” His analysis demonstrated that non-type conforming responses are dispreferred and indicate a problem with the presuppositions of the question (Raymond, ibid.:948). . HV: Mm.=Are your breasts alright. (0.7) Mom: They’re fi:ne no:w I’ve stopped leaking (.) so: Mom’s non-type conforming response resists a presupposition that there was never any problem. Non-type conforming responses are typically entirely missing from EFL textbooks. We don't even give students the option of omitting a turn- initial "yes" or "no."

- 163. Don't be short: The occurrence and non- occurrence of short- answer format replies

- 164. Should we be teaching the short-answers? Found in virtually every EFL textbook the world over, the so-called "short answers" are treated as bread-and-butter grammar and the default format for responding to polar questions. This following examines the occurrence, and more significantly, the non-occurrence of this format in naturally occurring L1 English speaker conversations. One immediate observation is that these short answers are rare and, from a CA perspective, rarity is often an initial indication that a practice is interactionally marked, which is to say that it does some special work. This raises several interesting questions. If short-answers are not common, what is found in their stead? When the short-answer format is used, what does the short-answer format accomplish that the far-more- common stand-alone "yes" or "no" token would not?