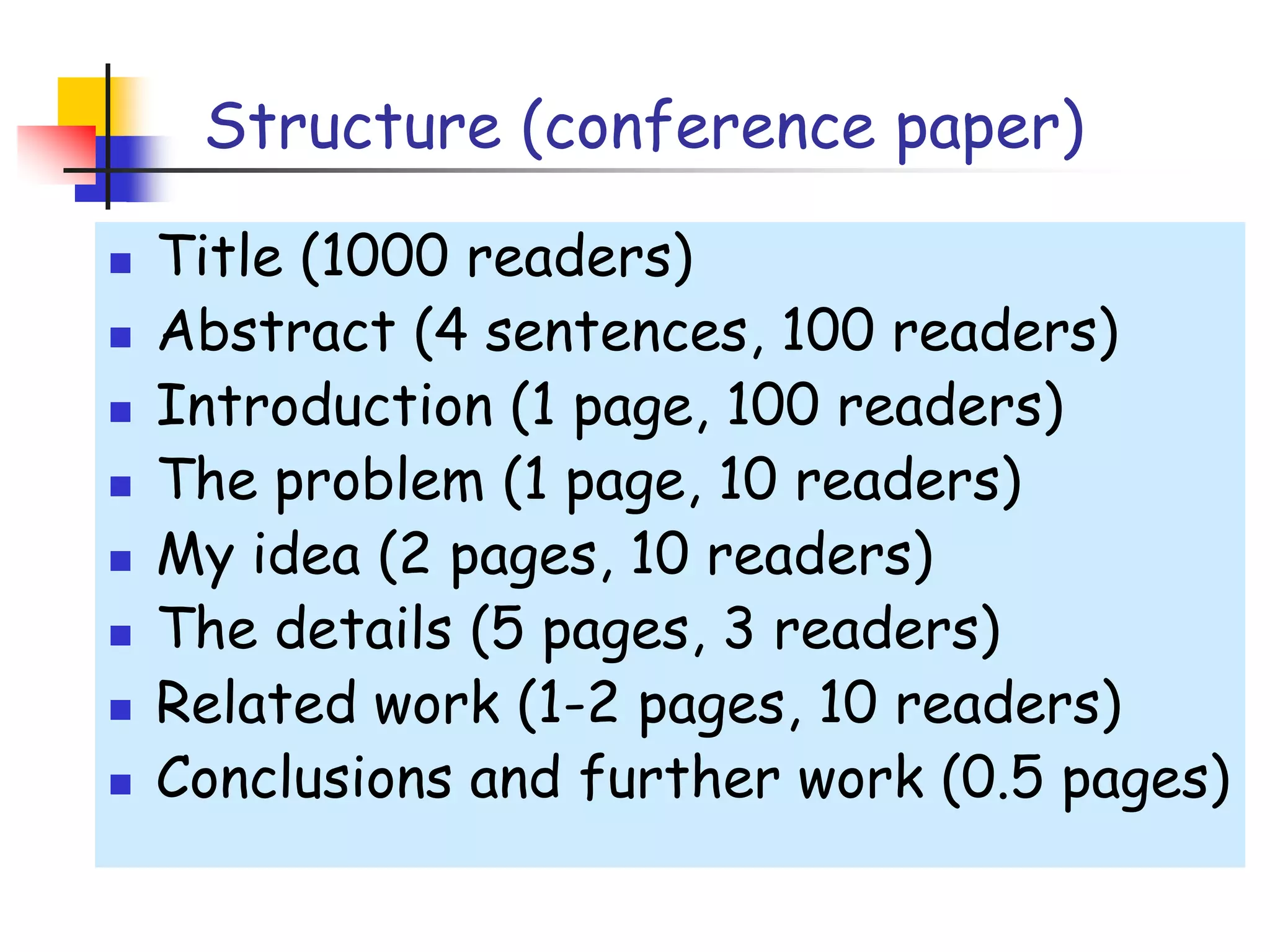

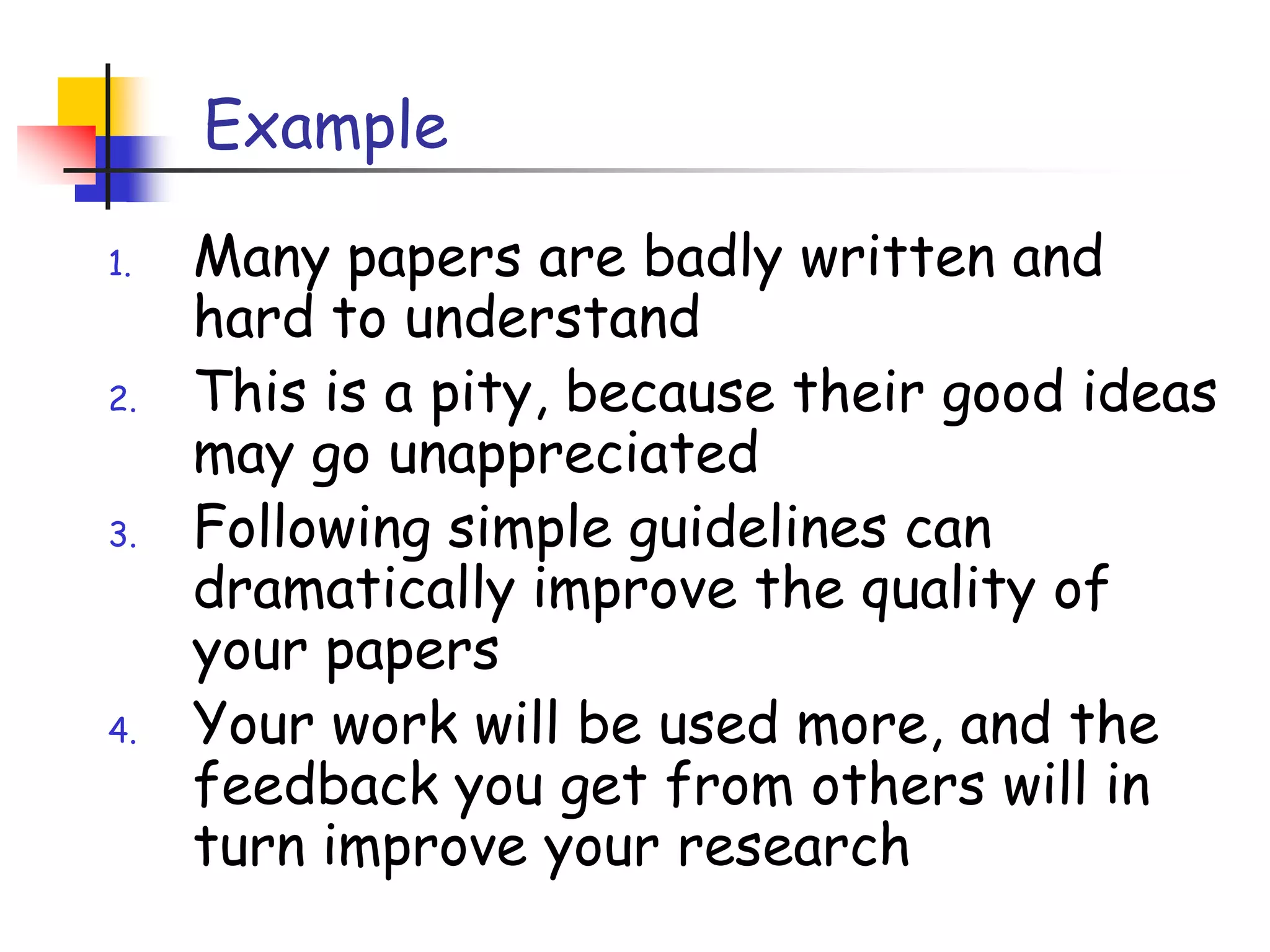

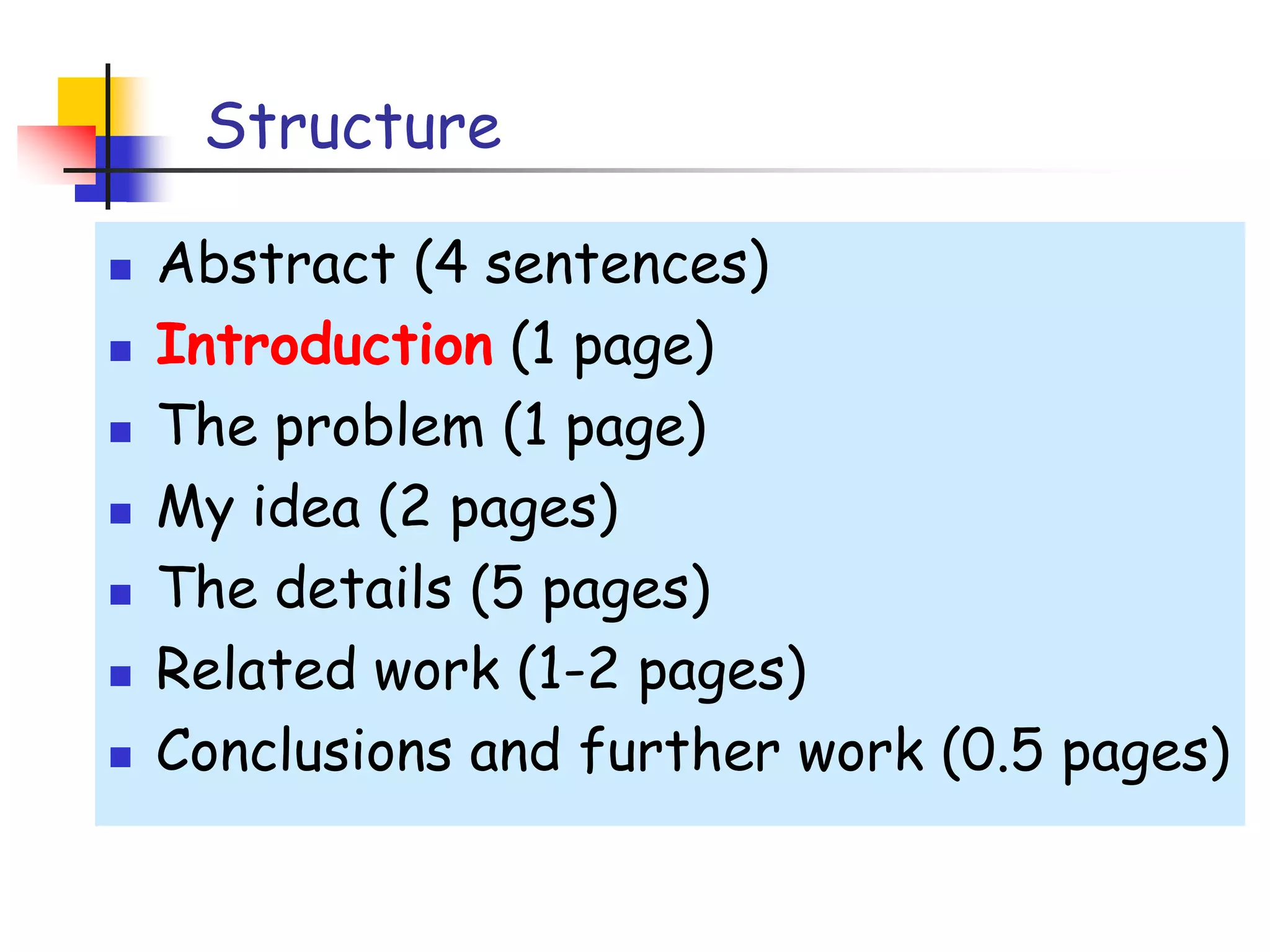

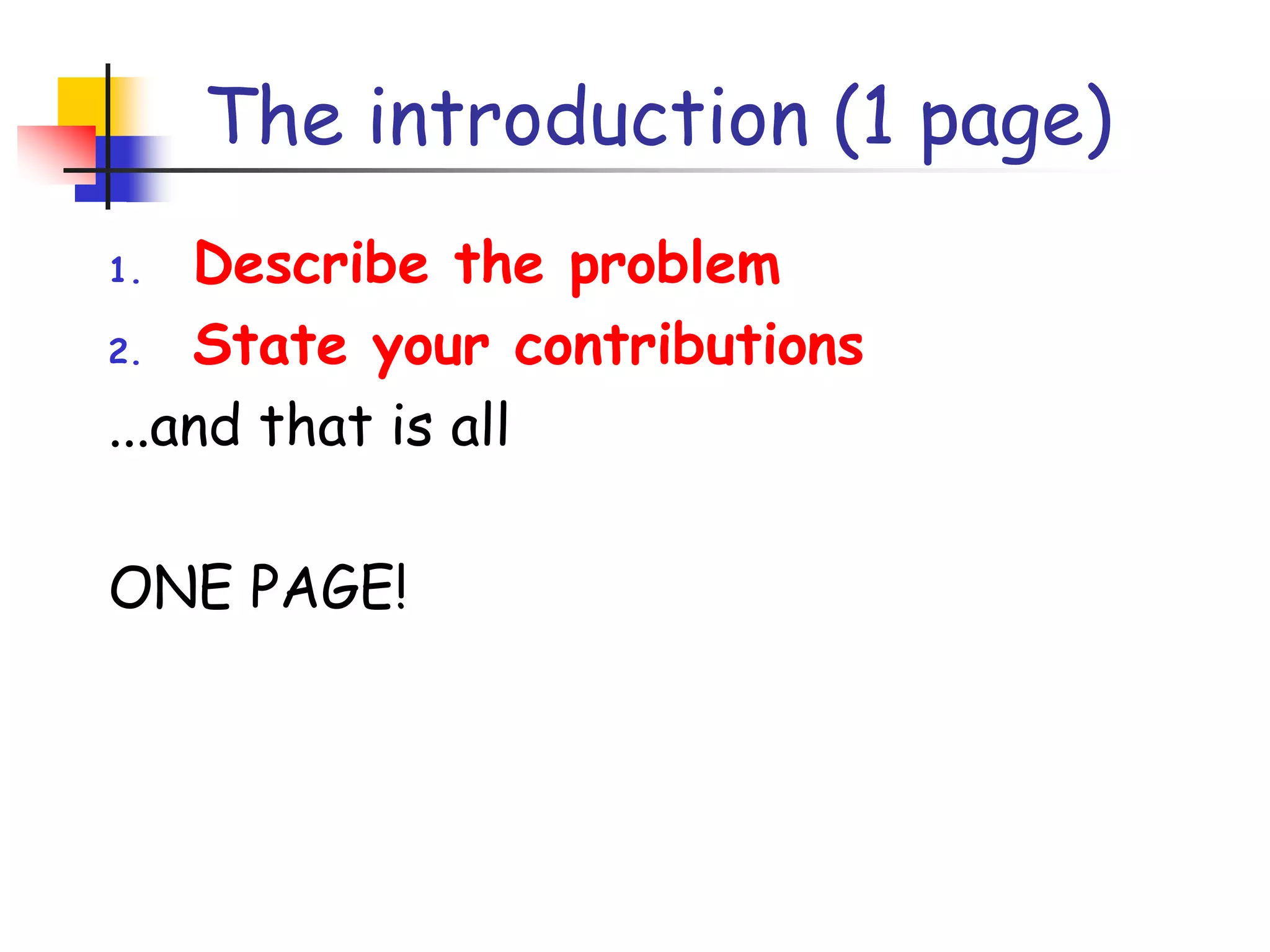

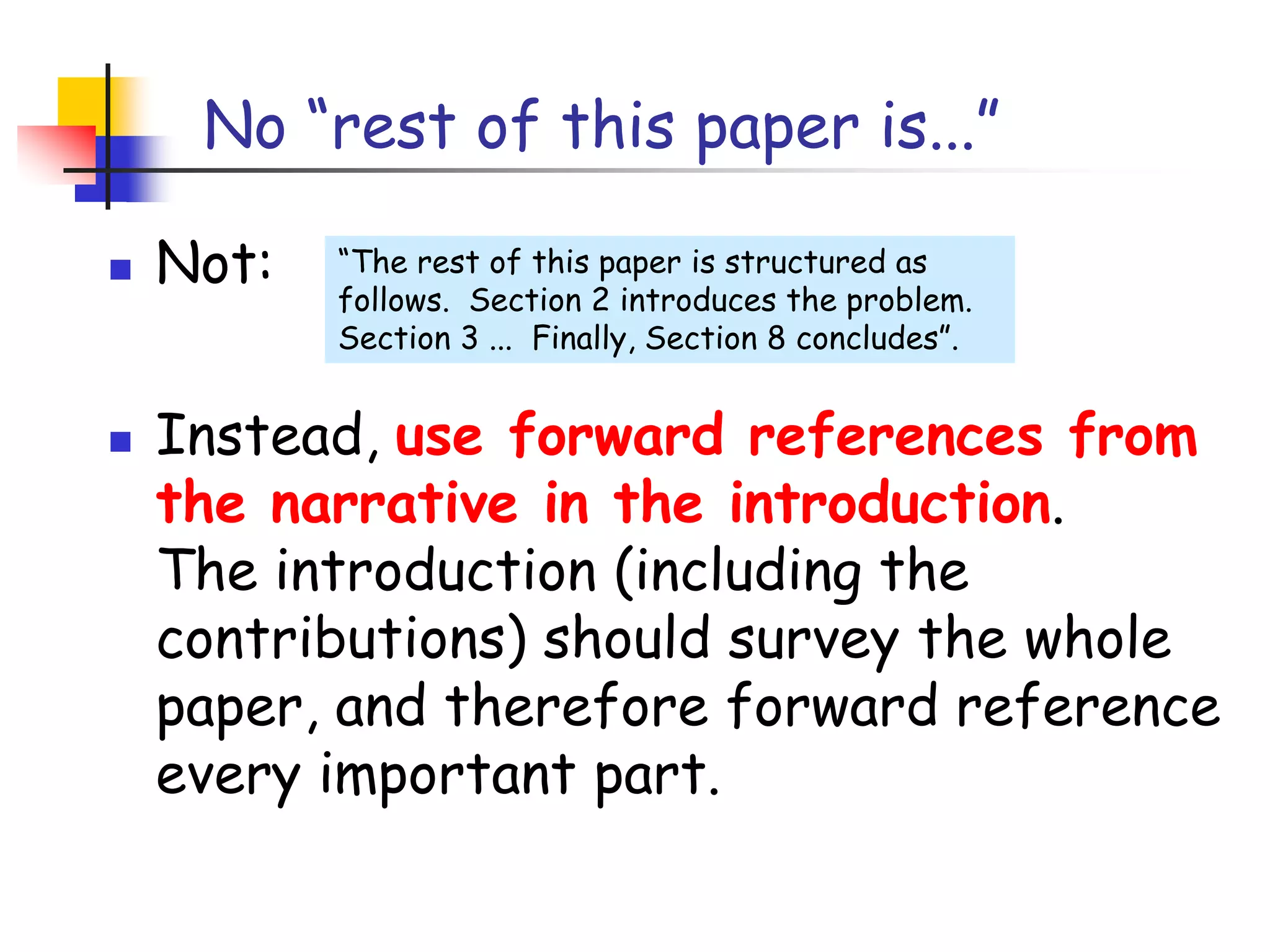

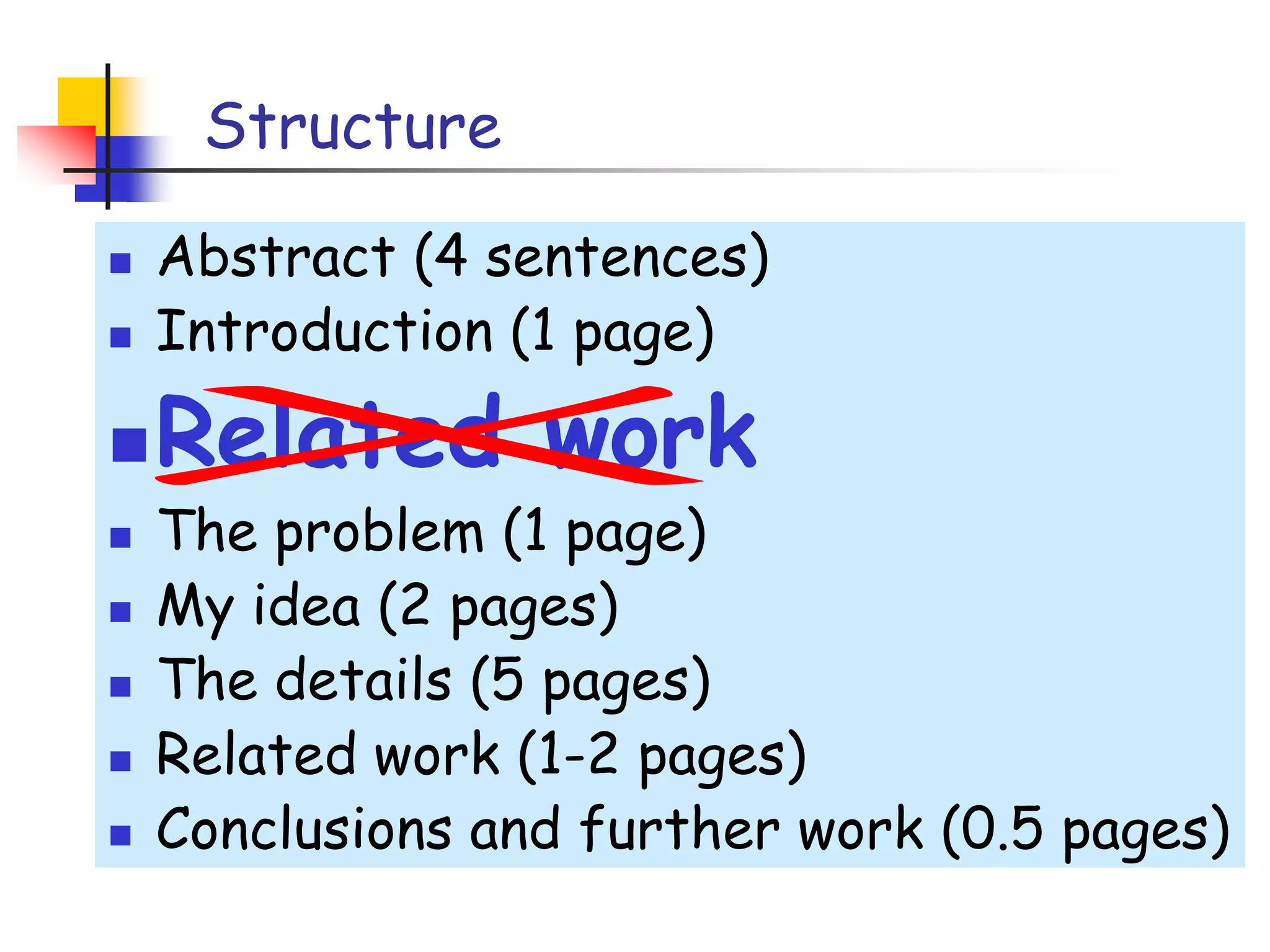

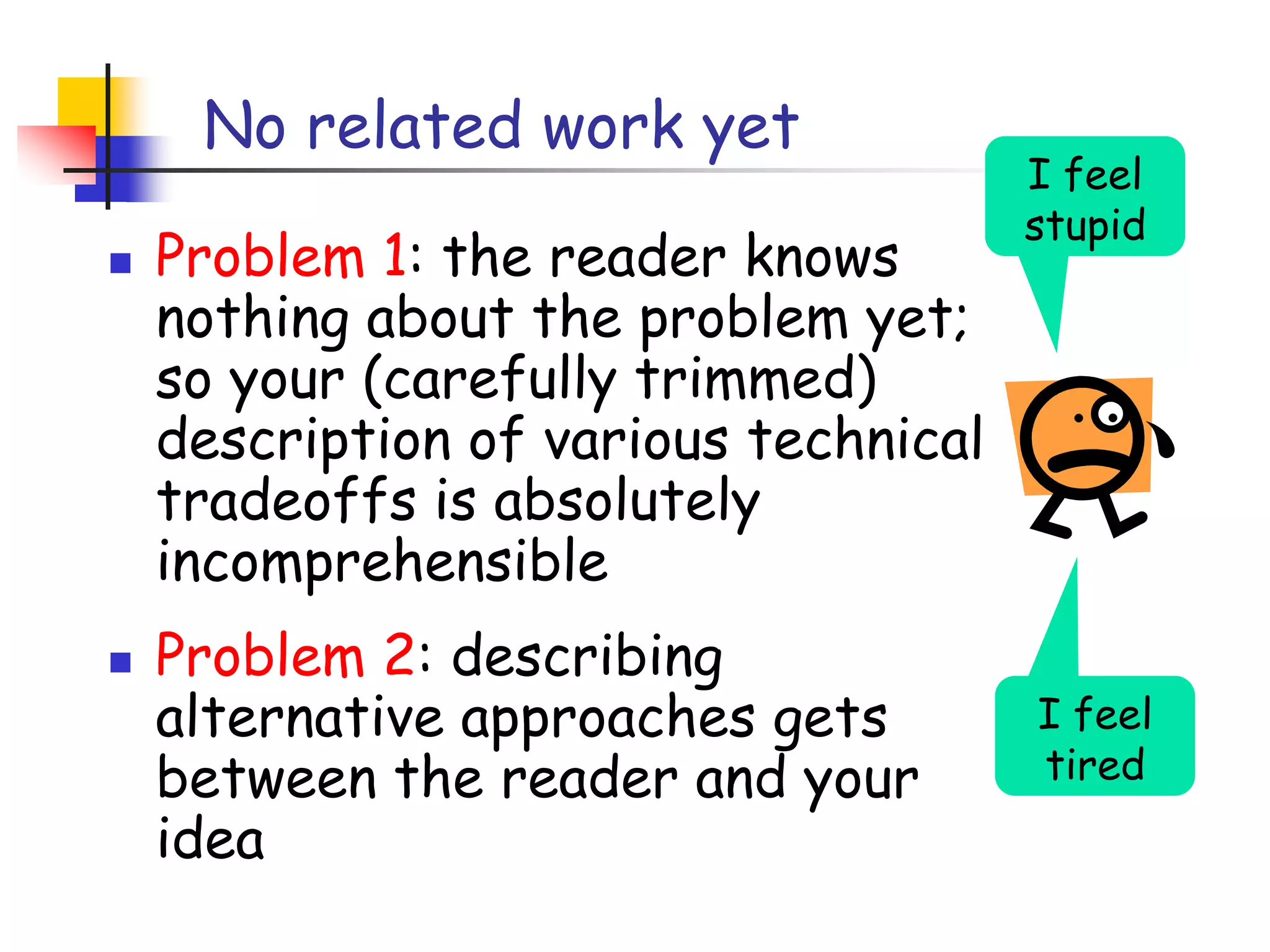

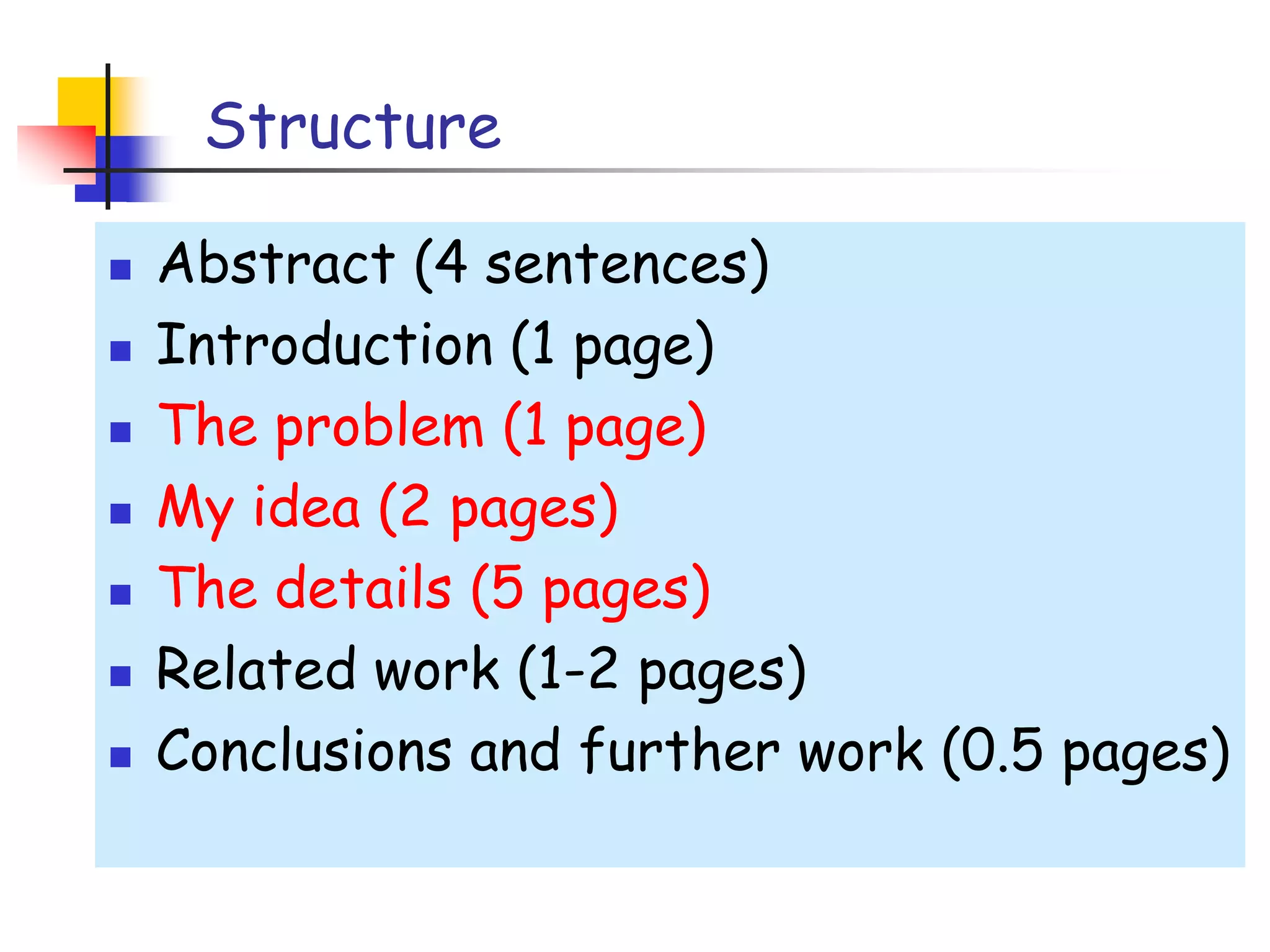

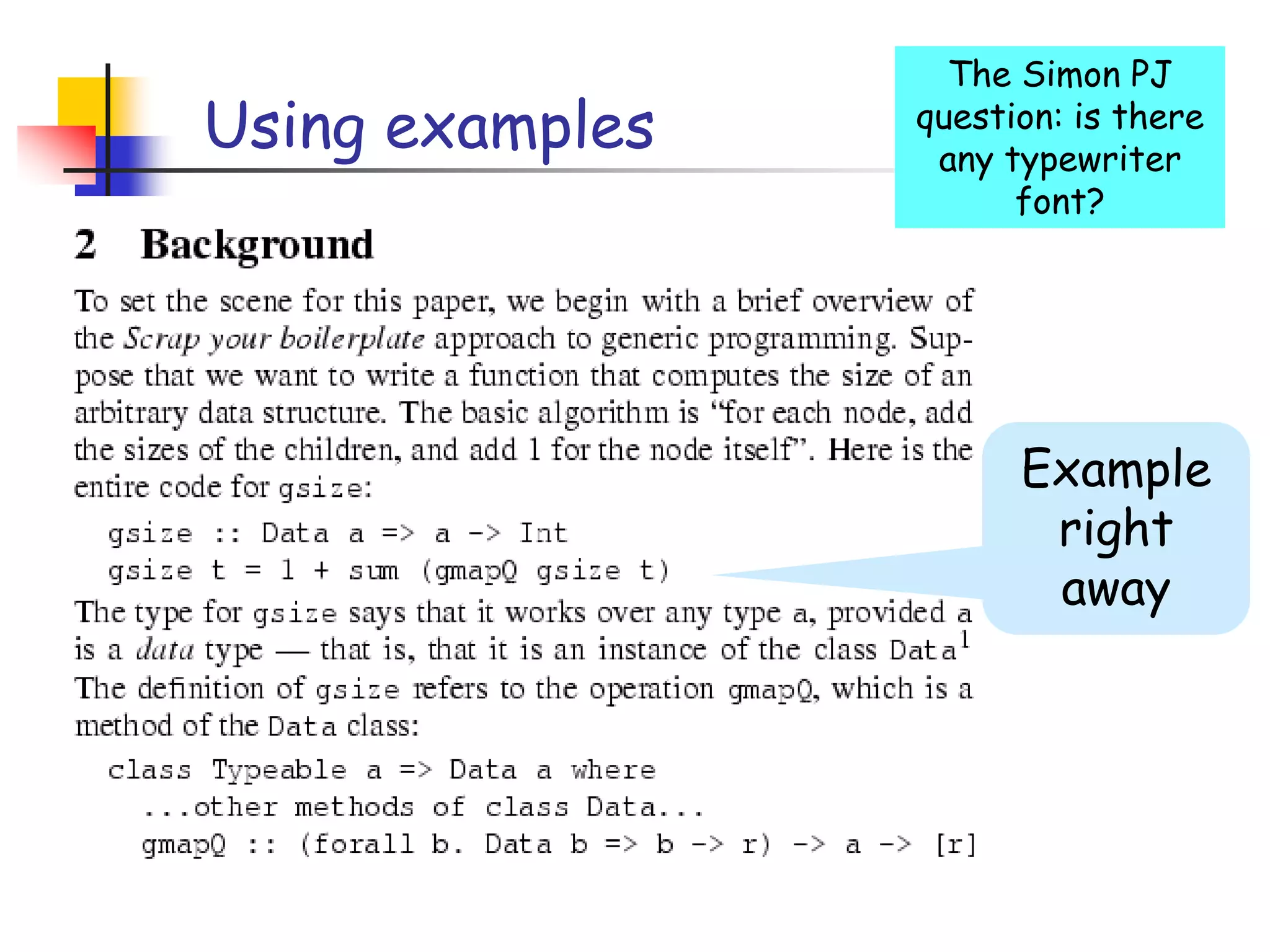

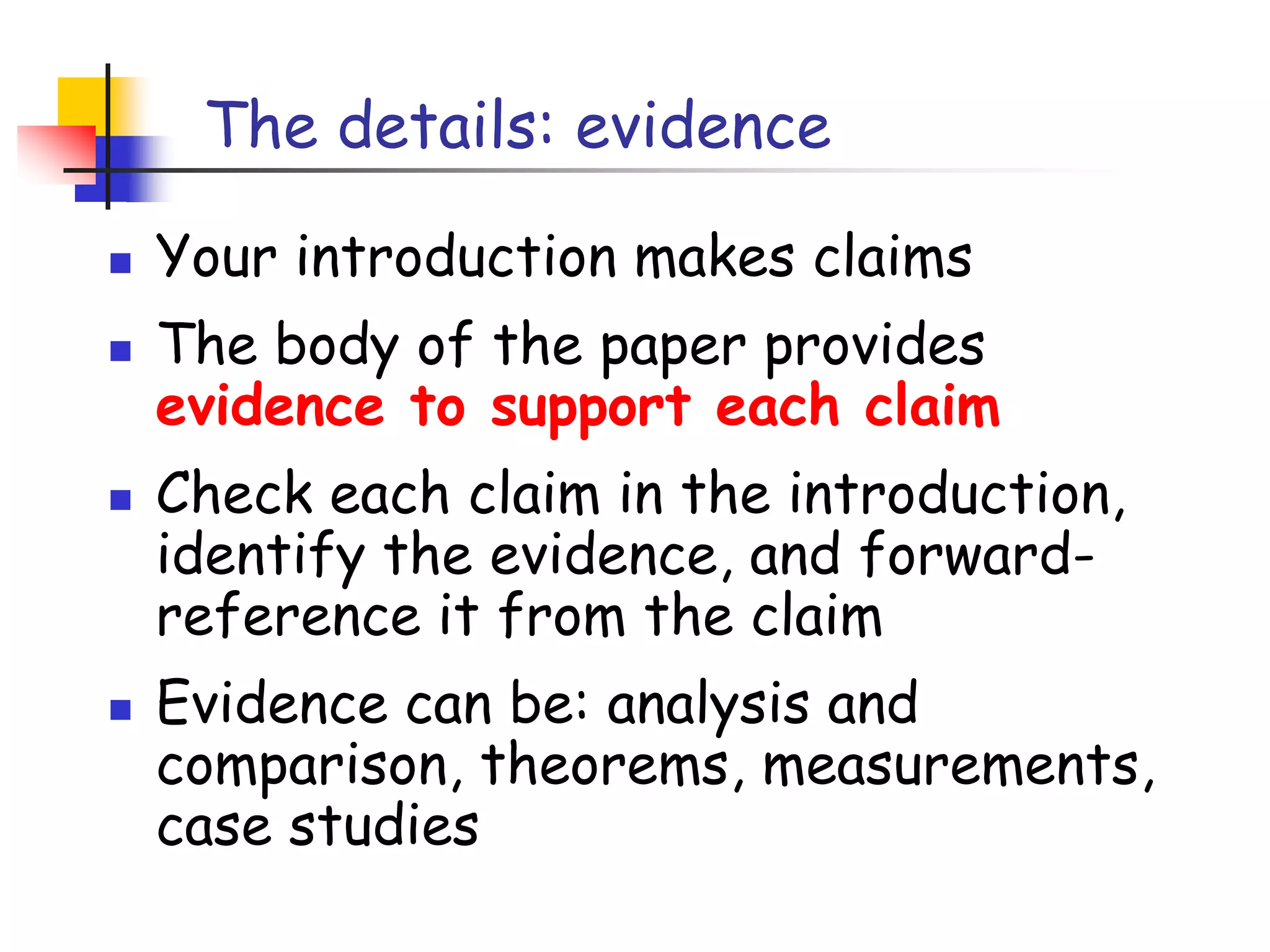

This document provides advice on how to write a great research paper. It recommends structuring the paper with an abstract, introduction, sections on the problem and idea, details supporting the claims, related work, and conclusions. The introduction should describe the problem, state the contributions, and reference later sections. Presenting the idea using examples before the general case helps readers. Providing evidence in later sections to support claims from the introduction is important. Give credit to other work and engage experts to improve the paper before publication.

![The abstractI usually write the abstract lastUsed by program committee members to decide which papers to readFour sentences [Kent Beck]State the problemSay why it’s an interesting problemSay what your solution achievesSay what follows from your solution](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/20090720writingapaper-100915055203-phpapp01/75/20090720-writing-a_paper-17-2048.jpg)

![Molehills not mountains“Computer programs often have bugs. It is very important to eliminate these bugs [1,2]. Many researchers have tried [3,4,5,6]. It really is very important.”“Consider this program, which has an interesting bug. <brief description>. We will show an automatic technique for identifying and removing such bugs”YawnCool!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/20090720writingapaper-100915055203-phpapp01/75/20090720-writing-a_paper-22-2048.jpg)

![No related work yet!Related workYour readerYour ideaWe adopt the notion of transaction from Brown [1], as modified for distributed systems by White [2], using the four-phase interpolation algorithm of Green [3]. Our work differs from White in our advanced revocation protocol, which deals with the case of priority inversion as described by Yellow [4].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/20090720writingapaper-100915055203-phpapp01/75/20090720-writing-a_paper-28-2048.jpg)

![Be generous to the competition. “In his inspiring paper [Foo98] Foogle shows.... We develop his foundation in the following ways...”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/20090720writingapaper-100915055203-phpapp01/75/20090720-writing-a_paper-41-2048.jpg)