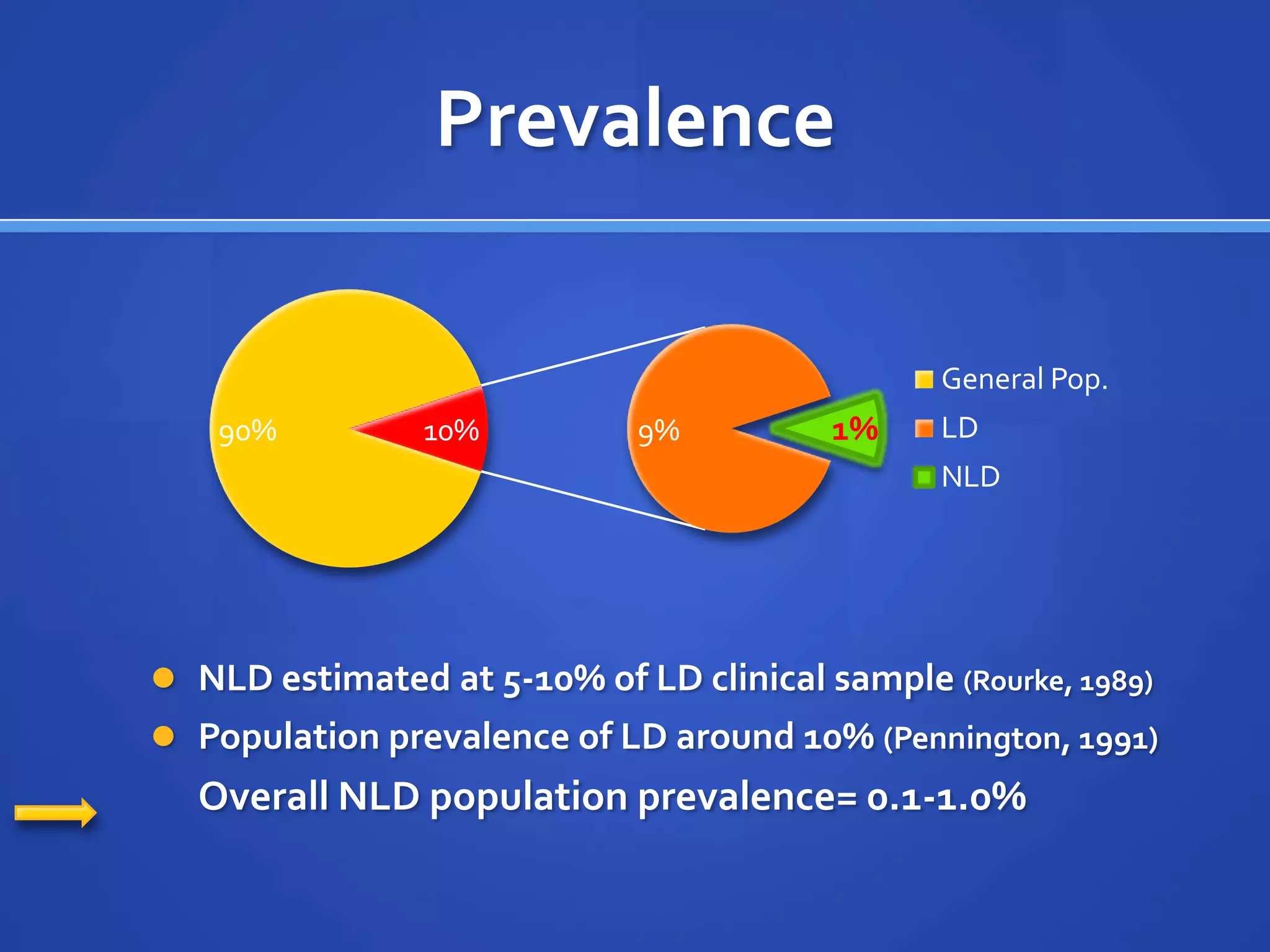

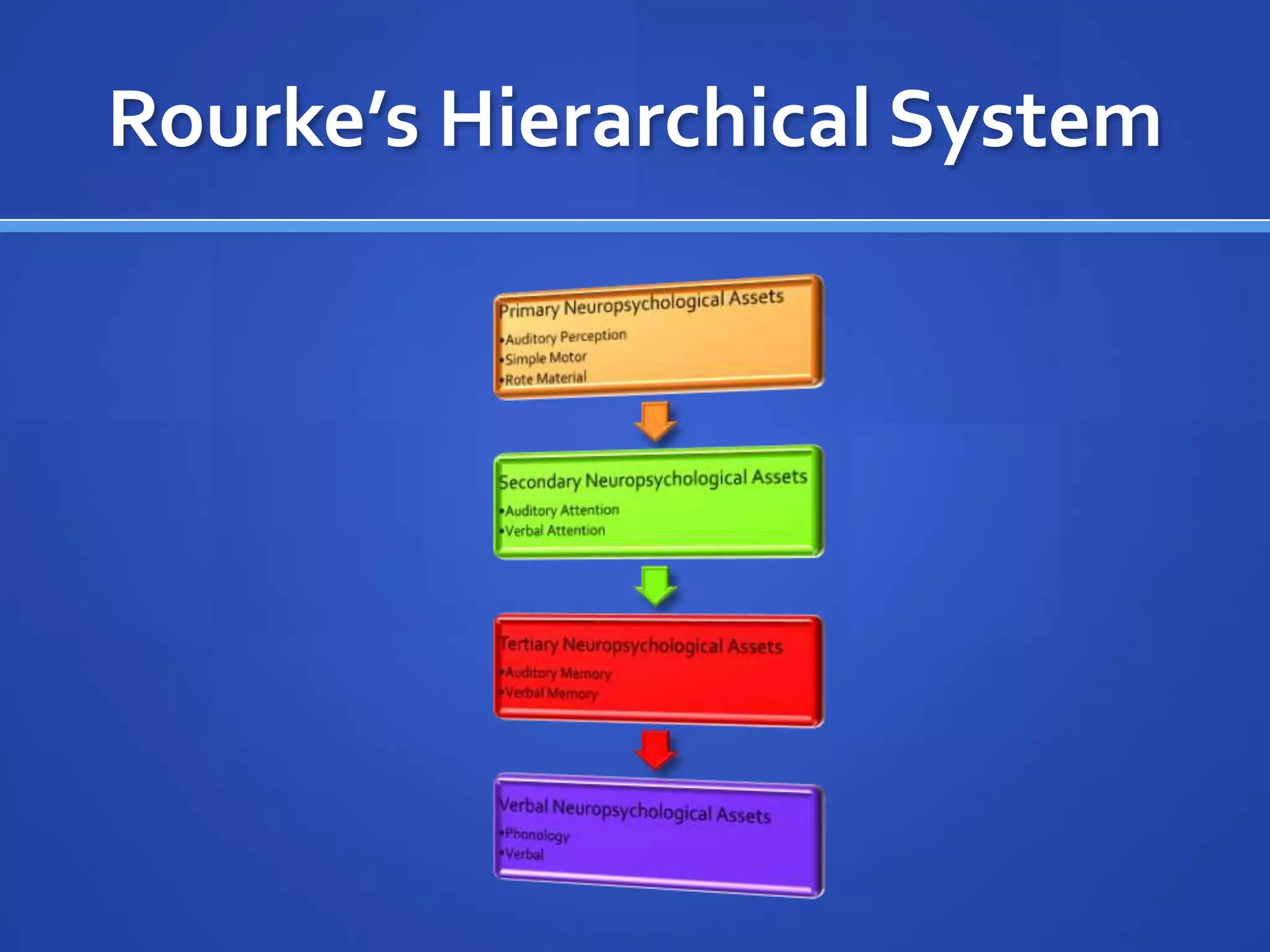

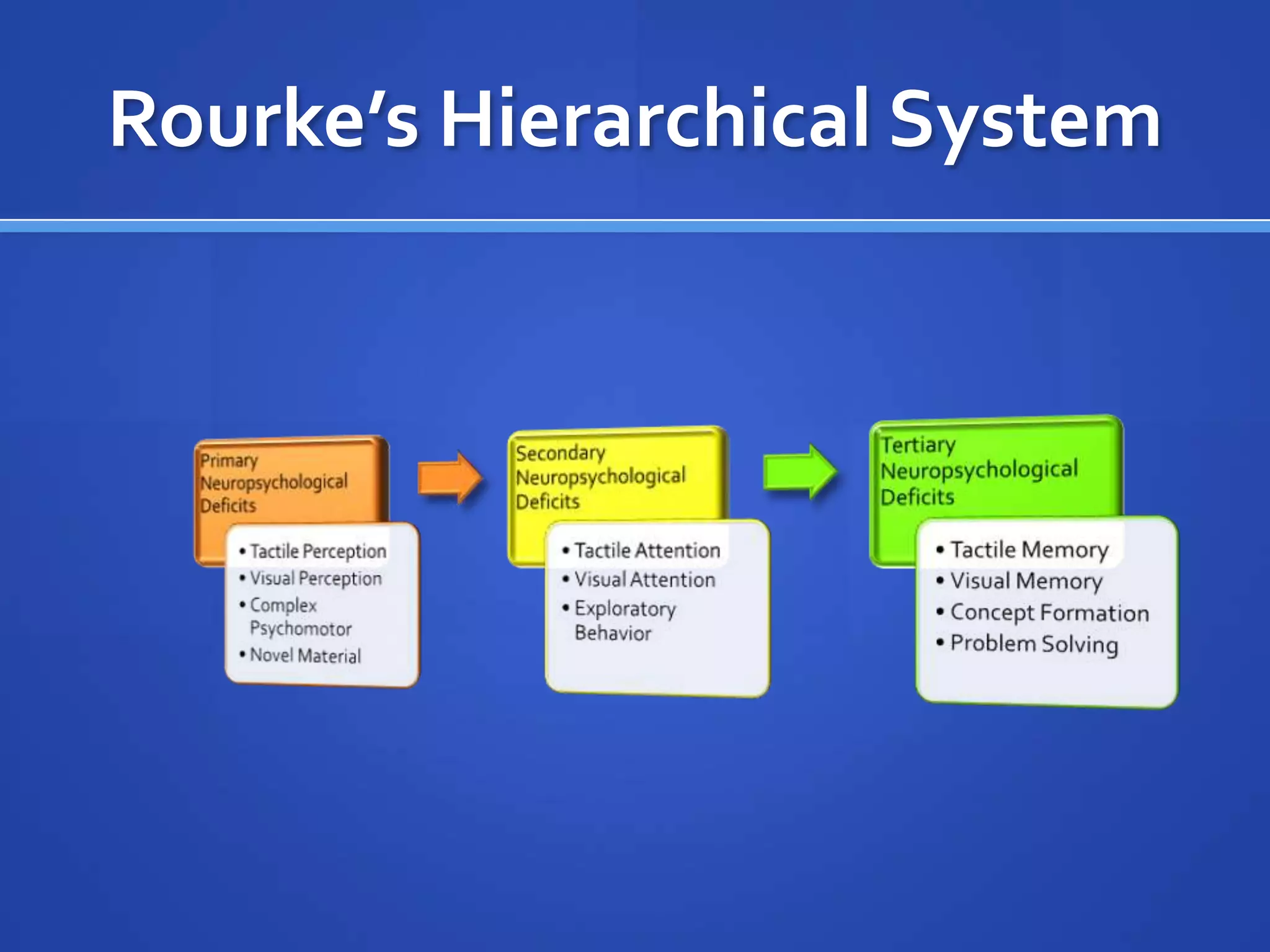

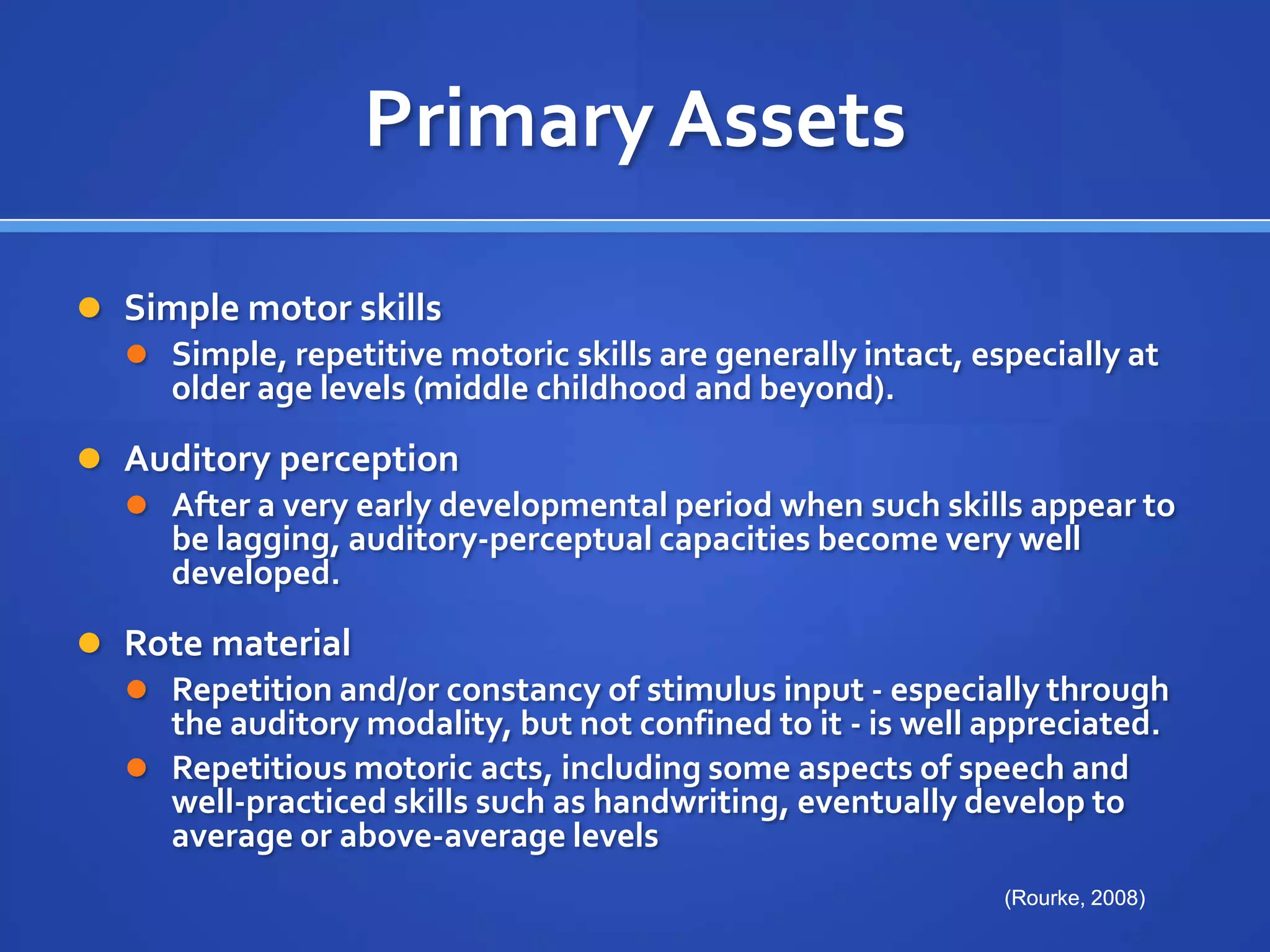

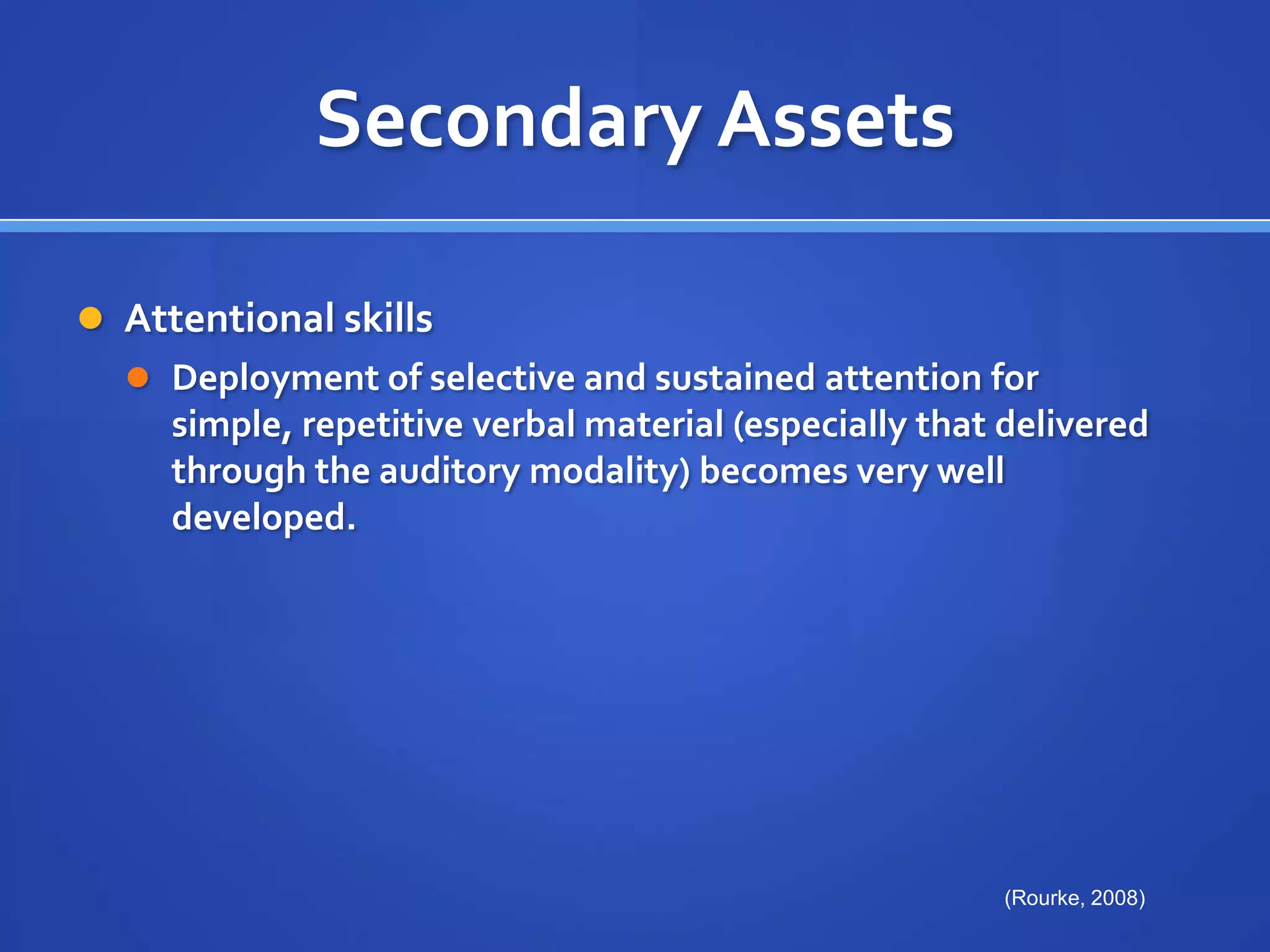

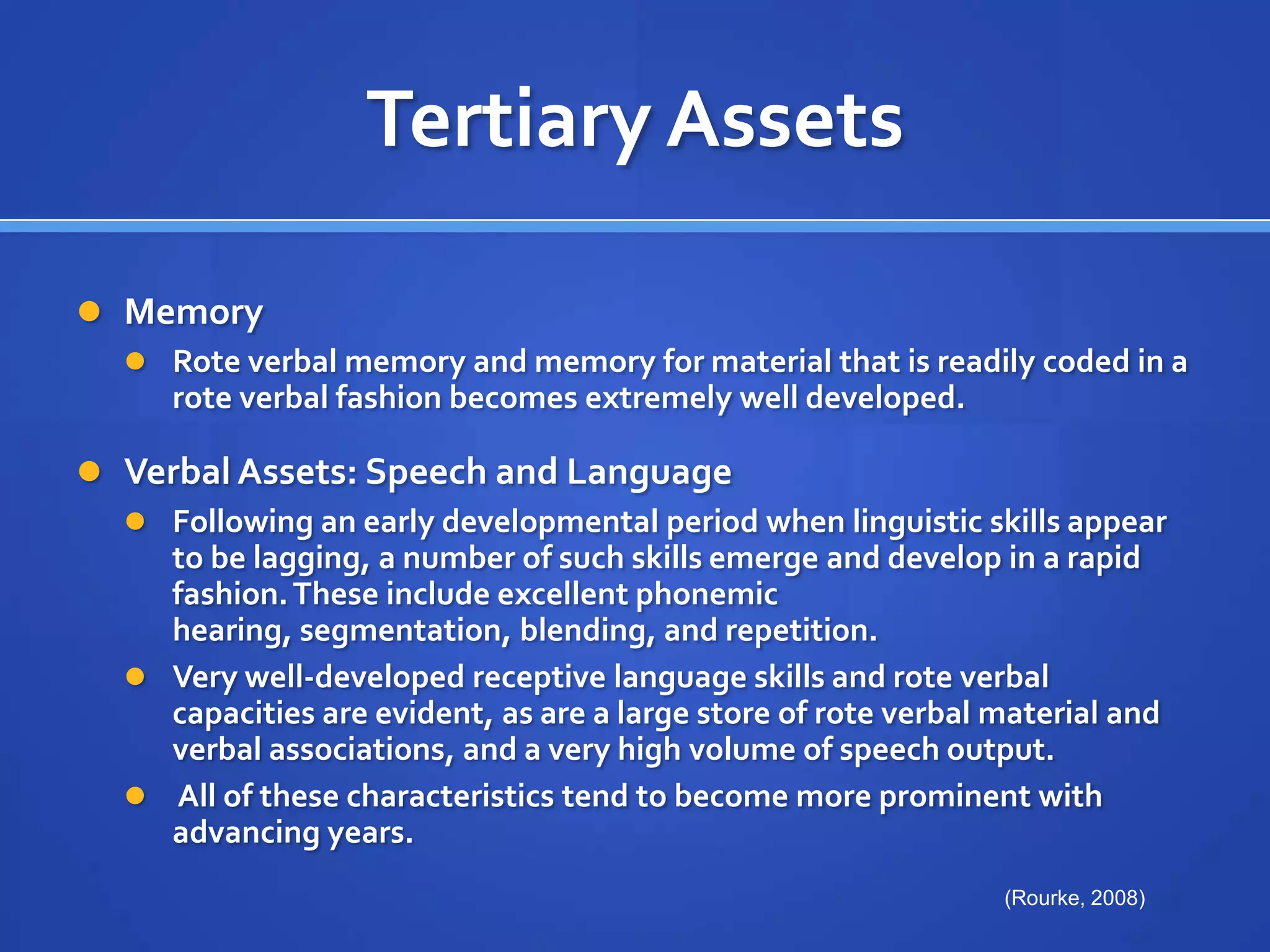

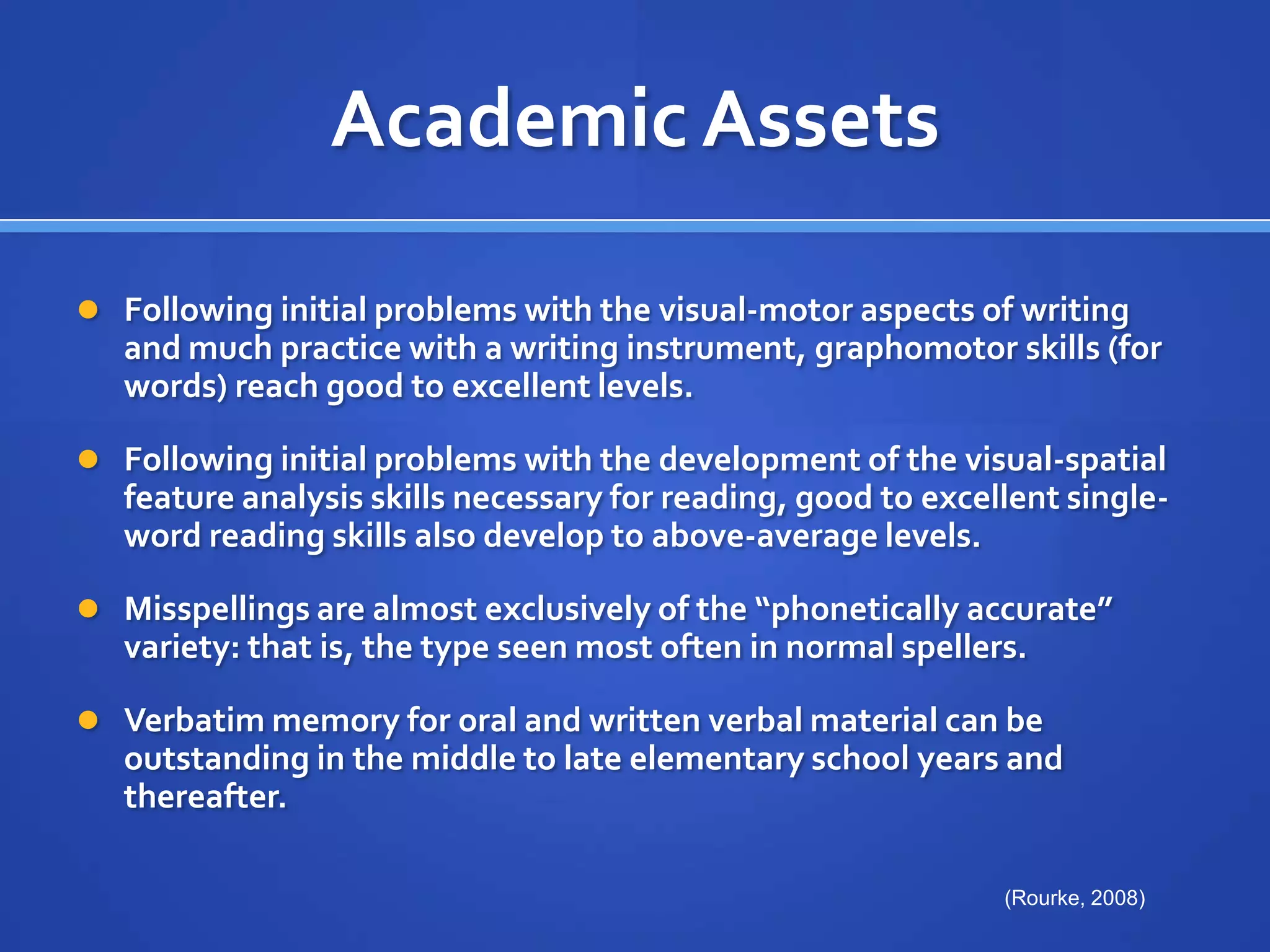

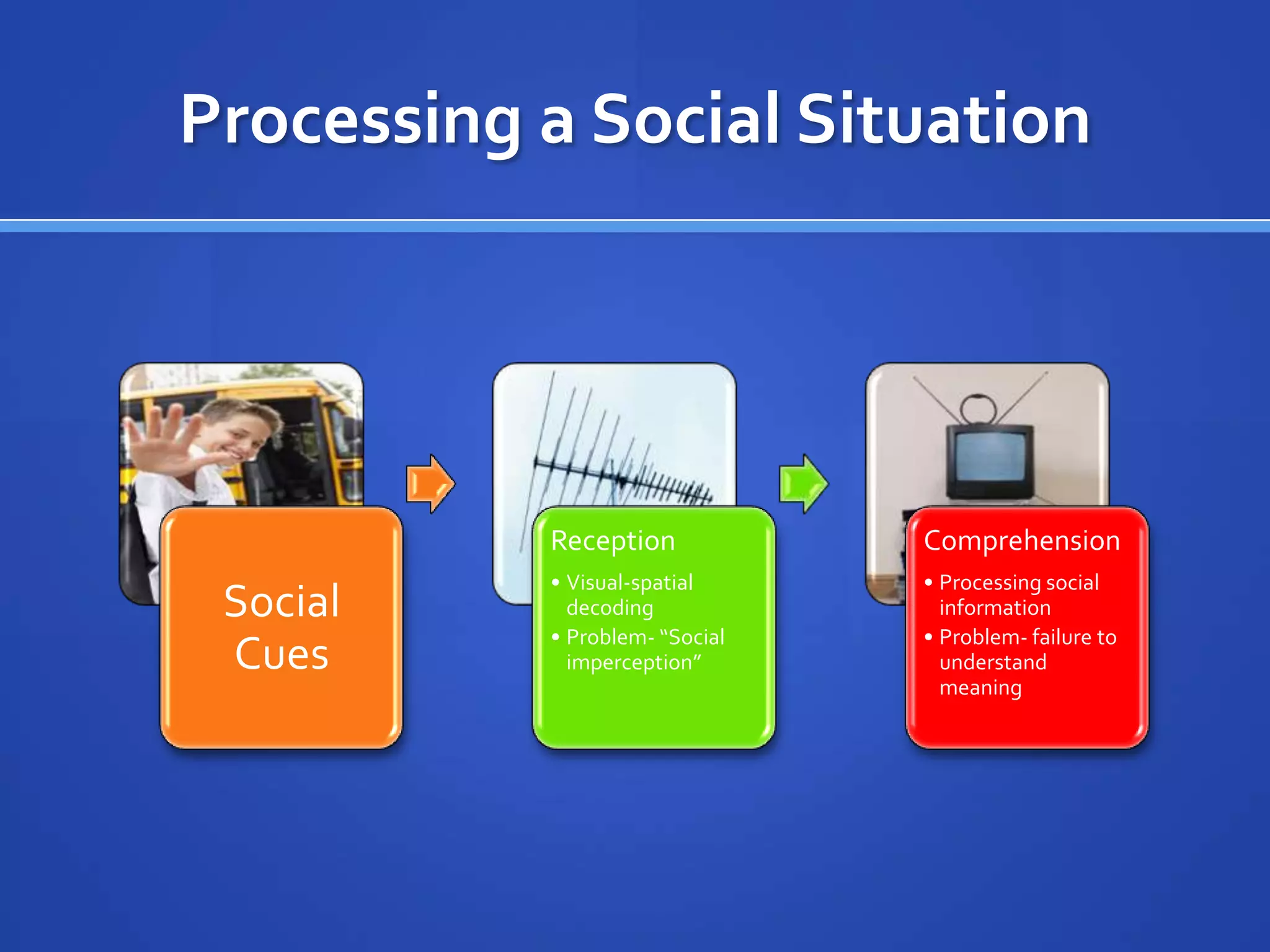

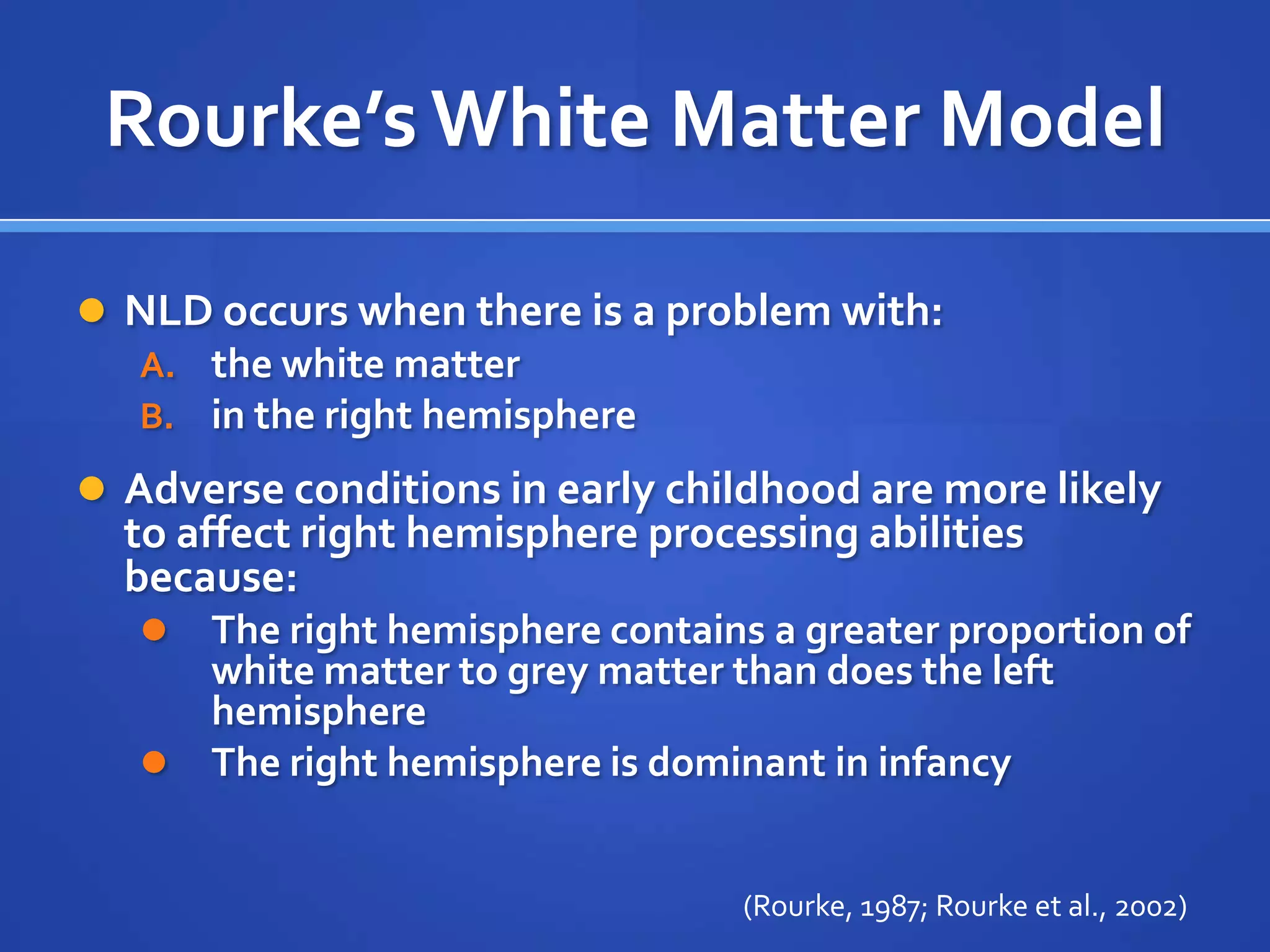

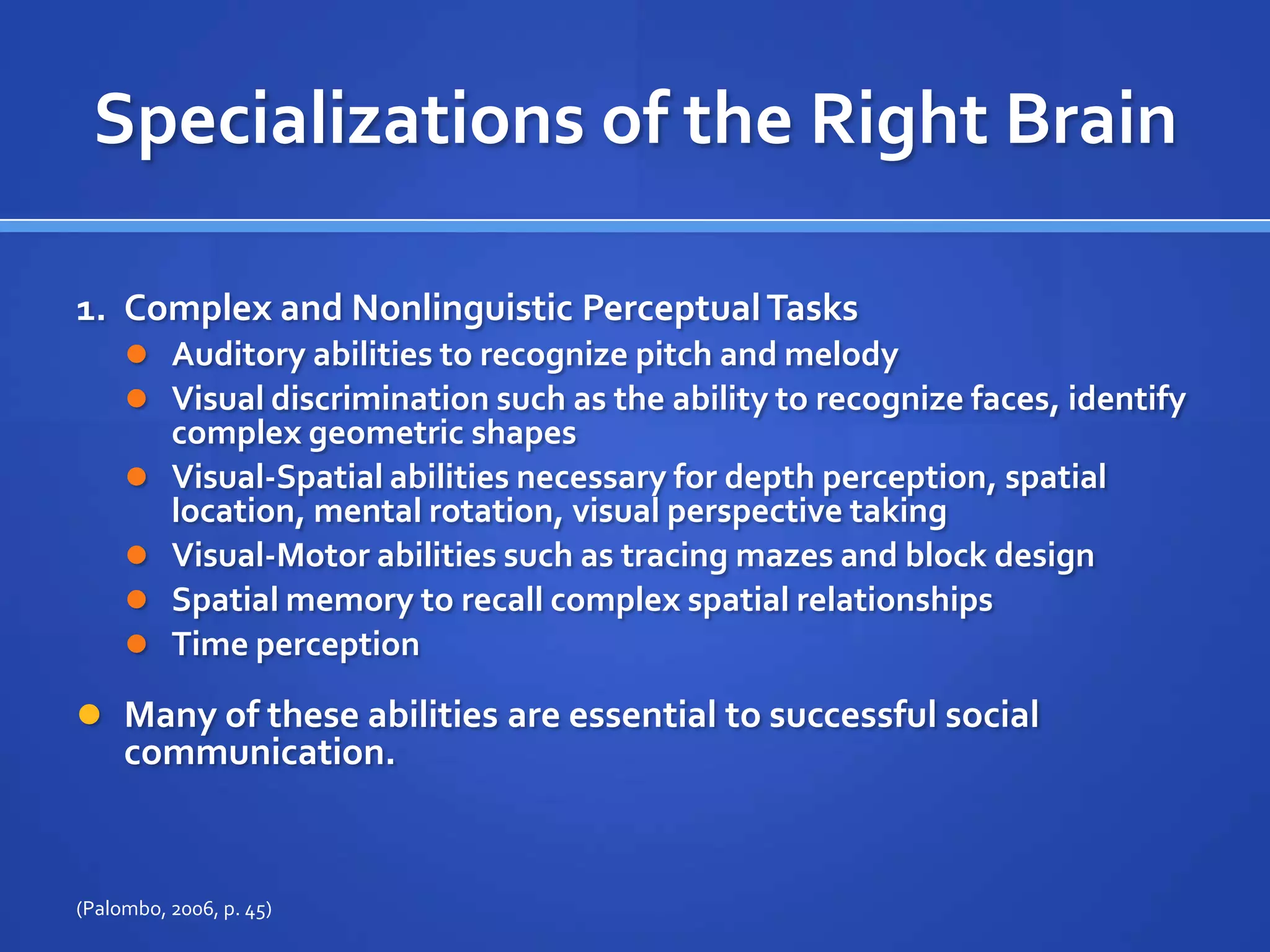

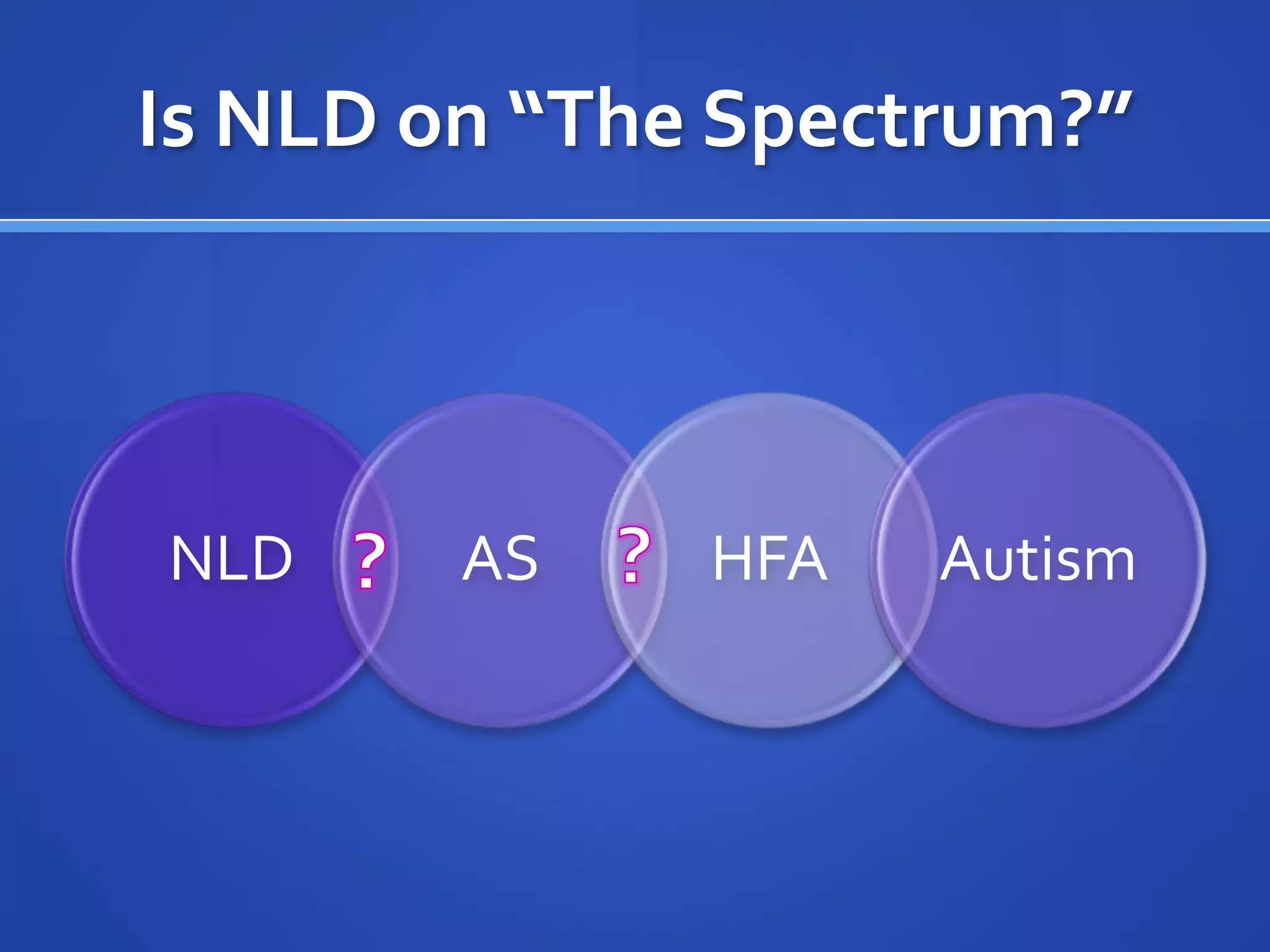

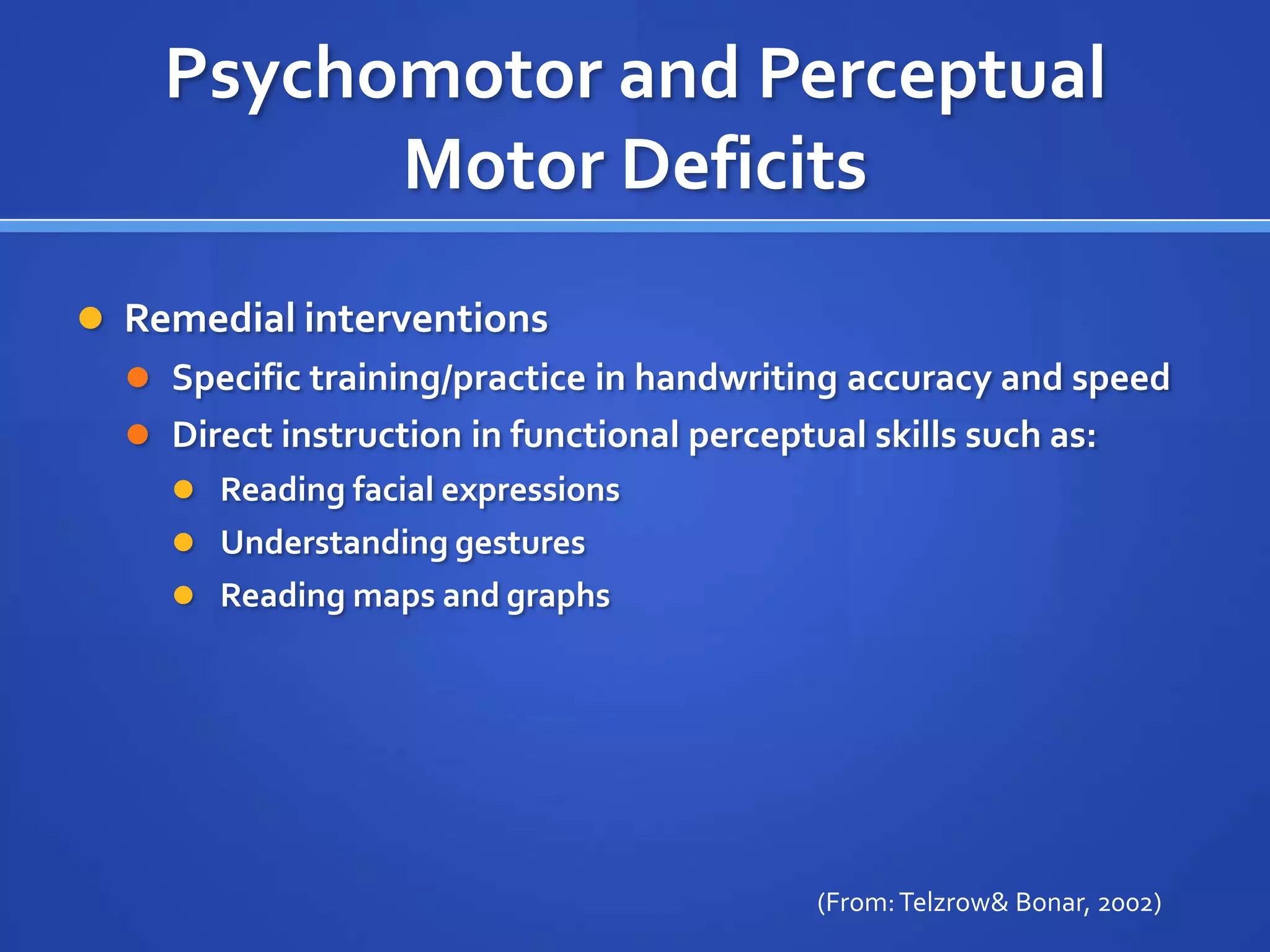

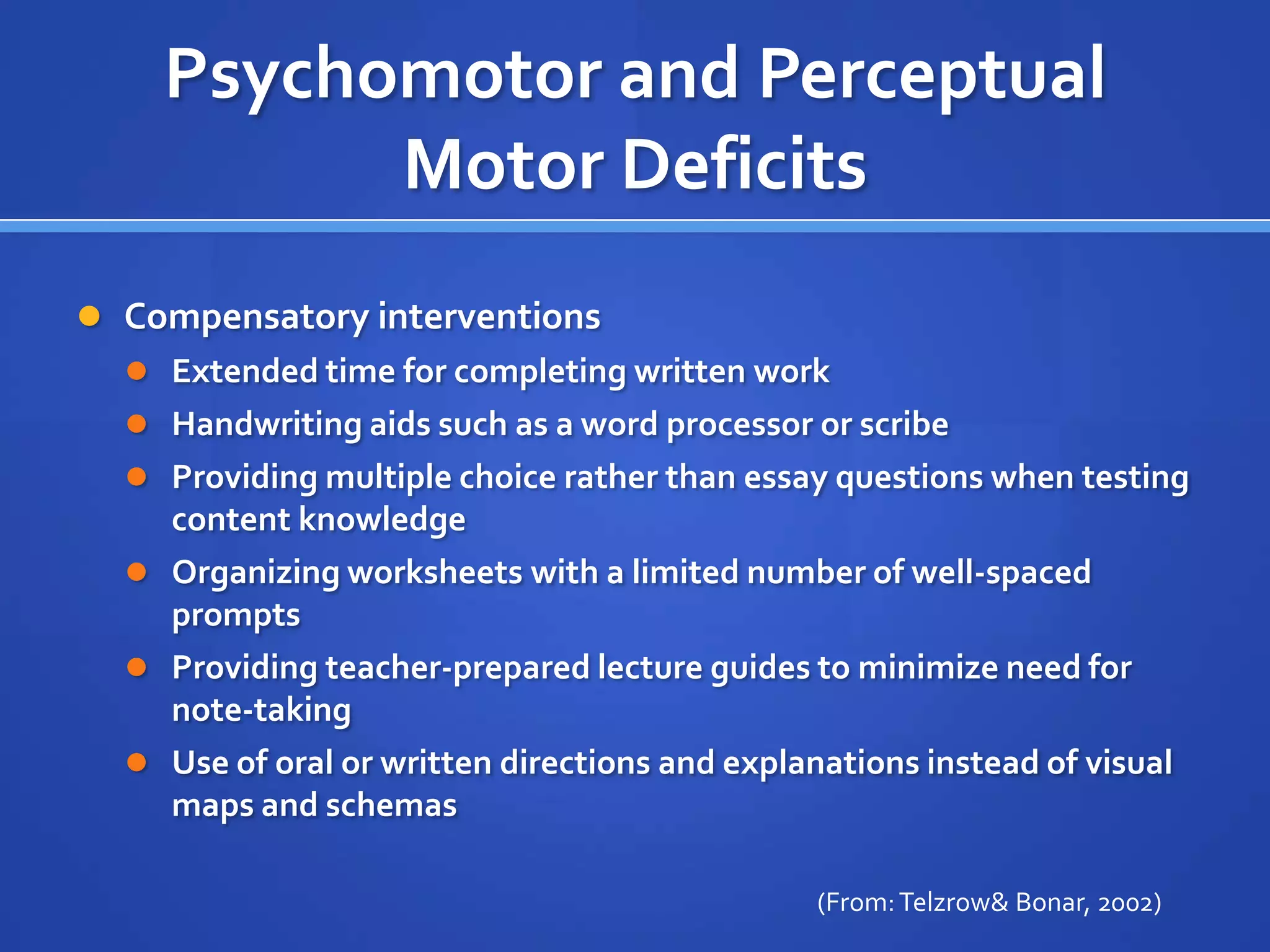

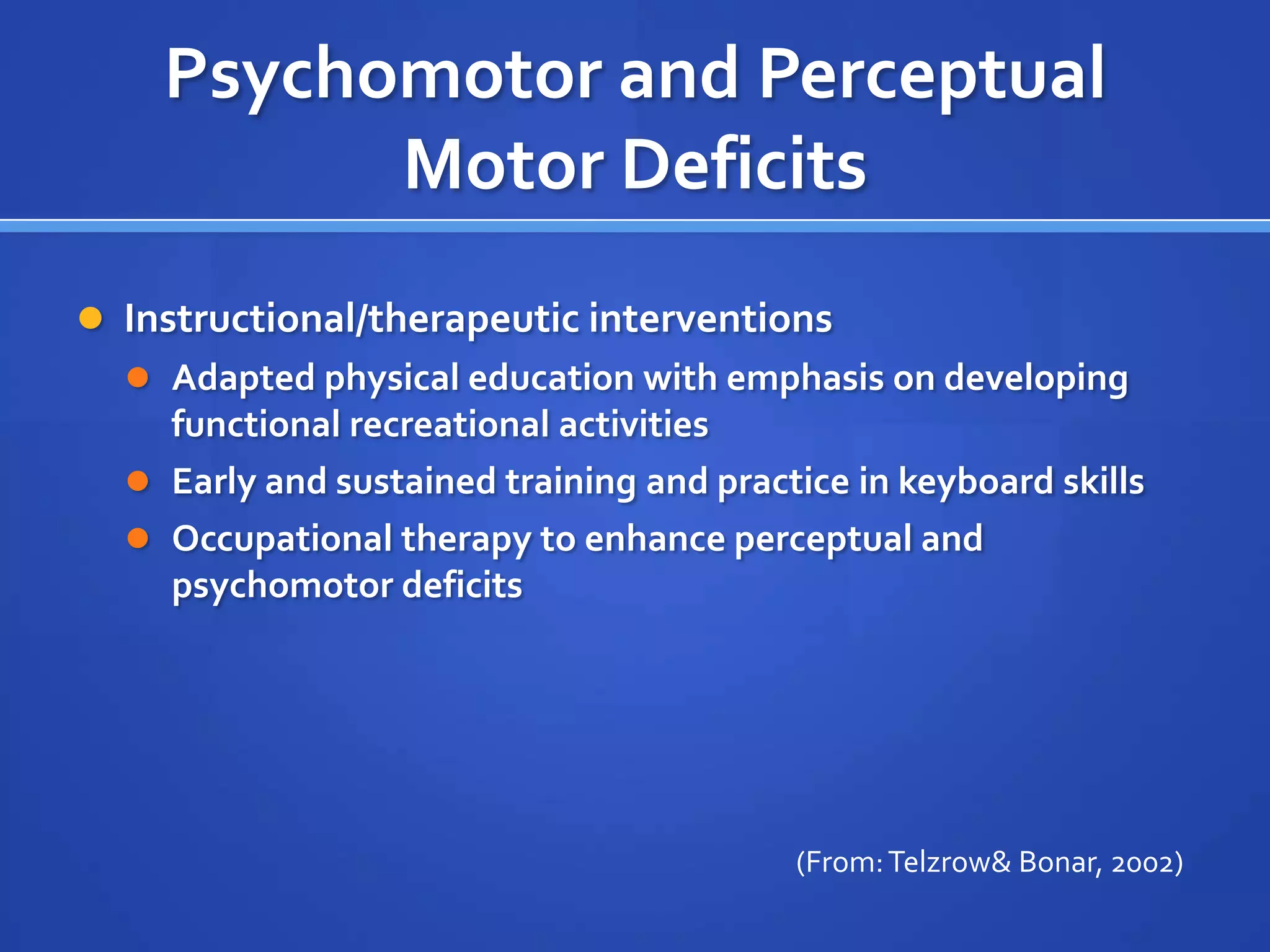

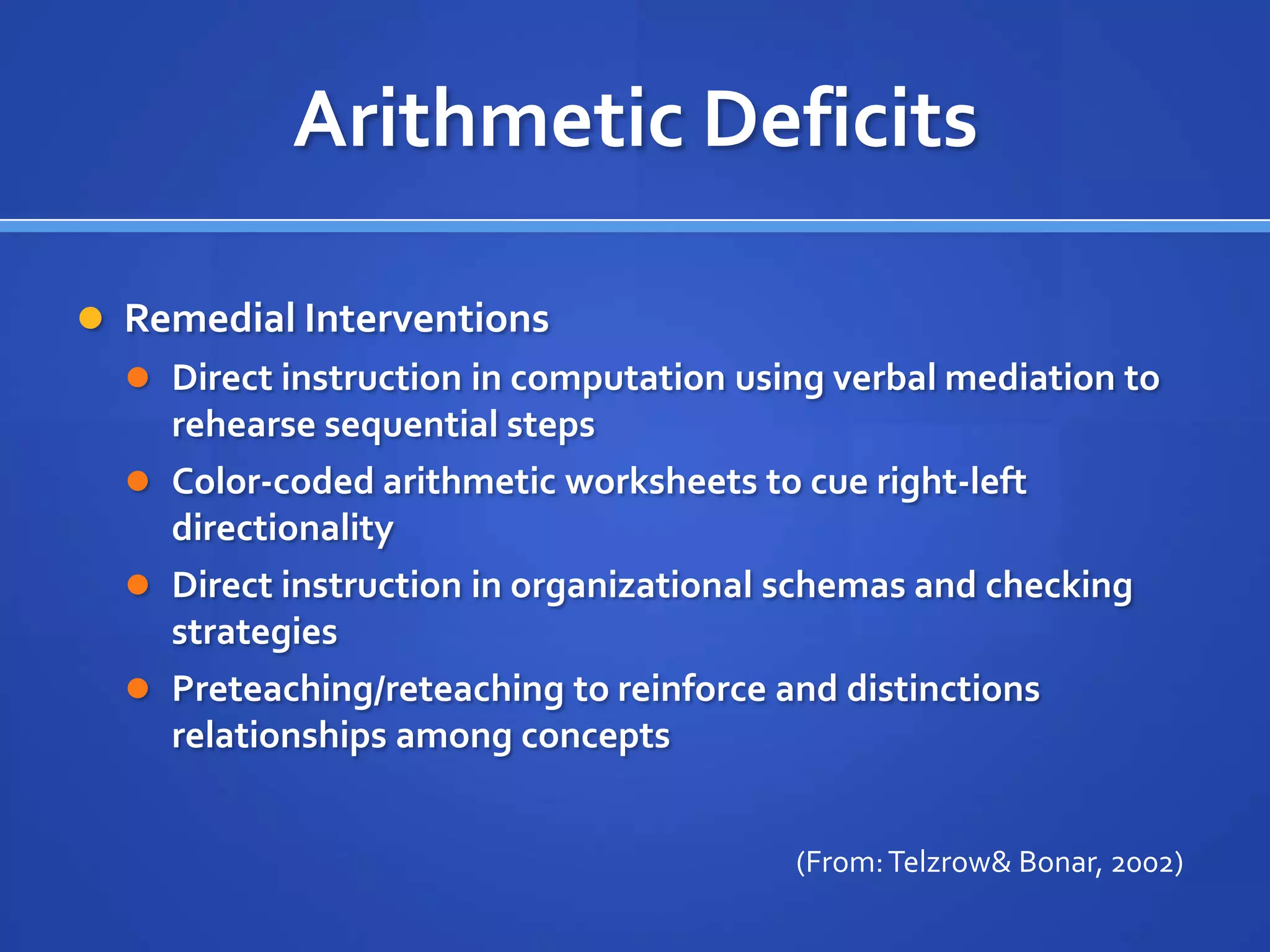

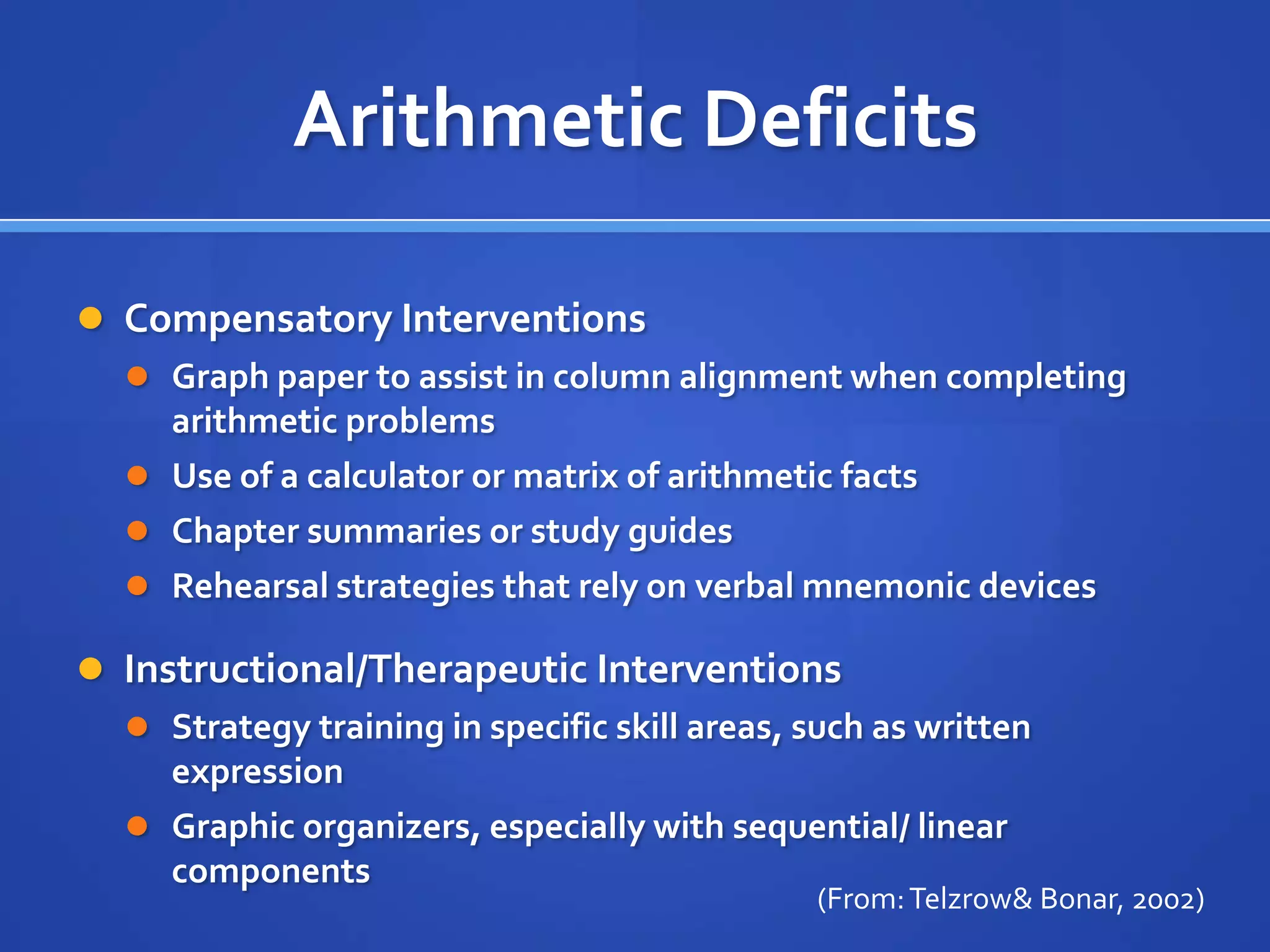

The document provides an overview of nonverbal learning disability (NLD), including its definition as a disorder that impairs nonverbal communication skills while verbal skills are relatively stronger. It discusses the initial identification of NLD in the 1960s and prevalence estimates. Key aspects of NLD are described, such as primary deficits in tactile perception, visual perception, and complex motor skills. Academic deficits including weaknesses in math, reading comprehension, and handwriting are also outlined.