Balanced MenusScenarioThe following is a lunch menu from a sea.docx

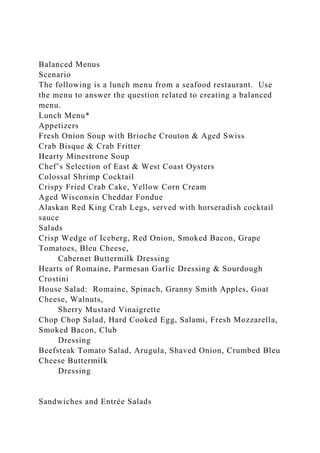

- 1. Balanced Menus Scenario The following is a lunch menu from a seafood restaurant. Use the menu to answer the question related to creating a balanced menu. Lunch Menu* Appetizers Fresh Onion Soup with Brioche Crouton & Aged Swiss Crab Bisque & Crab Fritter Hearty Minestrone Soup Chef’s Selection of East & West Coast Oysters Colossal Shrimp Cocktail Crispy Fried Crab Cake, Yellow Corn Cream Aged Wisconsin Cheddar Fondue Alaskan Red King Crab Legs, served with horseradish cocktail sauce Salads Crisp Wedge of Iceberg, Red Onion, Smoked Bacon, Grape Tomatoes, Bleu Cheese, Cabernet Buttermilk Dressing Hearts of Romaine, Parmesan Garlic Dressing & Sourdough Crostini House Salad: Romaine, Spinach, Granny Smith Apples, Goat Cheese, Walnuts, Sherry Mustard Vinaigrette Chop Chop Salad, Hard Cooked Egg, Salami, Fresh Mozzarella, Smoked Bacon, Club Dressing Beefsteak Tomato Salad, Arugula, Shaved Onion, Crumbed Bleu Cheese Buttermilk Dressing Sandwiches and Entrée Salads

- 2. All sandwiches served with choice of fries, soup, or house salad. Chicken Club with Toasted Brioche, Swiss Cheese, Smoked Bacon Steak Burger with Maytag Blue Cheese, Caramelized Bacon Maryland Crab Melt with Tillamook Cheddar Cheese, Jalapeno Corn Relish Soy Glazed Tuna Sandwich with Pickled Cucumber, Wasabi Mayonnaise Chicken Chopped Salad with Roasted Chicken, Asparagus, Goat Cheese, Dates, Corn, Sherry Vinaigrette Blackened Salmon Salad with Strawberry, Cantaloupe, Walnuts, Poppy Seed Dressing Black & Bleu Caesar with Flat Iron Steak, Bleu Cheese Dressing Prime Entrées Pecan Crusted Mountain Trout with Skillet Beans, Potato Puree, Brown Butter Shrimp Sautee with Angel Hair Pasta, Tabasco Cream Sauce Ginger Salmon with Snap Peas, Sticky Rice, Soy Butter Sauce Glazed Chilean Sea Bass with Baby Carrots, Mashed Potato Roasted Chicken with Asparagus, Truffle Macaroni & Cheese, Lemon Pan Jus Flat Iron Steak & Fries with Forest Mushroom Bordelaise New York Strip with Asparagus, Twice Baked Potatoes, Cabernet Jus Desserts Blueberry Lemon Cheesecake with Graham Cracker Crust and Blueberry Syrup Ten Layer Carrot Cake Chocolate Peanut Butter Pie Sorbet with Almond Cookie Baked Alaska – Pound Cake with Ice Cream, Toasted Meringue and Fresh Raspberries

- 3. *Adapted from Ocean Prime. Courtesy: Cameron Mitchell Restaurants Questions: 1) Which items are balanced so you could leave them on the menu as is? List at least one item in each category. 2) Which menu items could you modify to get a balanced item? List at least two items in each category. 3) Suggest a new balanced menu item (with ingredients) for any menu category which needs more balance. Directions: • Type your name, course name, case study # in the upper right corner of the first page. • Each case study analysis write up should be 1-2 pages, typewritten, double-spaced-ONLY ANSWERS. • 12 font : Times New Roman, 1 “ margin for all four side. • No cover page is required 2 Substance Use & Misuse, 46:808–818, 2011 Copyright C© 2011 Informa Healthcare USA, Inc. ISSN: 1082-6084 print / 1532-2491 online DOI: 10.3109/10826084.2010.538460 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Gender Differences in Substance Use, Consequences, Motivation to Change, and Treatment Seeking in People With Serious Mental Illness

- 4. Amy Drapalski1, Melanie Bennett2 and Alan Bellack1,2 1VISN 5 Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center, Veterans Affairs Maryland Health Care System, Baltimore, Maryland, USA; 2Department of Psychiatry, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA Gender differences in patterns and consequences of substance use, treatment-seeking, and motivation to change were examined in two samples of people with serious mental illness (SMI) and comorbid substance use disorders (SUDs): a community sample not cur- rently seeking substance abuse treatment (N = 175) and a treatment-seeking sample (N = 137). In both groups, women and men demonstrated more similar- ities in the pattern and severity of their substance use than differences. However, treatment-seeking women showed greater readiness to change their substance use. Mental health problems and traumatic experi- ences may prompt people with SMI and SUD to enter substance abuse treatment, regardless of gender. Keywords dual diagnosis, serious mental illness, gender differences, motivation to change, treatment-seeking INTRODUCTION Substance use disorders (SUDs) among people with se- rious mental illness (SMI) are widespread and harmful. Depending on the psychiatric diagnosis, rates of lifetime drug and alcohol use disorders in people with SMI gen- erally top between 30% and 45% (Reiger et al., 1990; Winoker et al., 1998). Despite the high prevalence, rela- tively little is known about differences in substance use

- 5. and its consequences among subgroups of people with SMI, or whether subgroup differences are clinically im- portant. One important subgroup is women with SMI and comorbid SUDs. Women with SMI have been found to have different patterns of illness onset and course (Angermeyer, Kuhn, & Goldstein, 1990; Childers & 1The journal’s style utilizes the category substance abuse as a diagnostic category. Substances are used or misused; living organisms are and can be abused. Editor’s note. This research was supported by grants RO1 DA 012265 (Dr. Bellack) and R01 DA11753 (Dr. Bellack) from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the VISN 5 Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center. Address correspondence to Dr. Amy Drapalski, VISN 5 Mental Illness Research Education and Clinical Center, Veterans Affairs Maryland Health Care System, 10 North, Greene Street, Baltimore, MD 21201; E- mail: [email protected] Harding, 1990; Kawa et al., 2005; Kennedy et al., 2005; Kessing, 2004; McGlashan & Bardenstein, 1990), better social functioning (Mueser, Bellack, Morrison, & Wade, 1990), and more positive outcomes than men (Childers & Harding, 1990; McGlashan & Bardenstein, 1990; Test, Burke, & Wallisch, 1990). Research with primary sub- stance users without co-occurring mental illness has also found gender differences in substance use patterns (Greenfield et al., 2007; Pelissier & Jones, 2005), con- sequences (Greenfield et al., 2007; Zilberman, Taveres, Blume, & el Guedbaly, 2003), and treatment utilization (Greenfield et al., 2007; Weisner & Schmidt, 1992). The high rate of substance use among individuals with SMI and the apparent gender differences in illness course and patterns of substance use in other groups of substance

- 6. abusers suggest the need to look at the ways in which women with SMI and SUDs may differ from men, as well as whether and how these differences need to be addressed in treatment. Few studies have examined gender differences in peo- ple with dual SMI and SUDs. Those that have fo- cused on gender differences have looked at how women differ from men in terms of the nature of their sub- stance use. For example, several studies have exam- ined whether women with SMI and SUDs differ from men in terms of patterns and severity of substance use and types of substances abused.1 Overall, men and women with SMI have been found to show similar pat- terns and severity of substance use (Brunette & Drake, 1997; Gearon, Nidecker, Bellack, & Bennett, 2003). Dif- ferences in drug of choice have been reported, with women reporting higher rates of heroin and cocaine dependence (Gearon, Nidecker, et al., 2003) and men GENDER DIFFERENCES IN SUD AND SMI 809 higher rates of cannabis dependence (Brunette & Drake, 1997; Gearon, Nidecker, et al., 2003; Test et al., 1990) and alcohol abuse (Frye et al., 2003). One fairly consis- tent gender difference is in consequences of substance use. Several studies have found higher rates of physical and sexual victimization, greater physical health prob- lems, and fewer legal problems in women with SMI and SUDs than in men (Brunette and Drake, 1997; Test et al., 1990), and dually diagnosed women report higher rates of posttraumatic stress disorder than men (Grella, 2003). Other research has found that women with SMI are un- derrepresented in substance abuse treatment (Alexander,

- 7. 1996; Bellack & Gearon, 1998; Comtois & Ries, 1995; Gearon & Bellack, 1999), with women seeking treatment only when negative consequences become severe (Rach- Beisel, Scott, & Dixon, 1999; Weisner & Schmidt, 1992). These findings of differences in substances of abuse, consequences, and representation in treatment would sug- gest that women with dual SUD and SMI have unique rea- sons for seeking treatment or issues surrounding access to care. However, research has not fully addressed whether this is the case. Watkins, Shaner, and Sullivan (1999) interviewed 21 men and women outpatients with SMI about their treatment needs and their reasons for and bar- riers to seeking substance abuse treatment. Few gender differences were identified. The most frequent treatment needs for both men and women were assistance with housing and finances. Reasons for engagement in treat- ment centered on staying out of legal trouble, although men more often reported family pressure to attend treat- ment. Both men and women reported concerns about le- gal consequences of admitting to use, fear, and paranoia as barriers to care. The authors speculate that such fac- tors may disproportionately influence women to stay away from treatment because of their high rates of victimization (Watkins et al., 1999). Grella (2003) examined gender dif- ferences in readiness for treatment, treatment needs, and barriers to care among 400 individuals with dual disor- ders recruited from several residential drug user treatment programs. Participants were asked to rate the importance of 25 different service needs (e.g., treatment/recovery, health, family, basic needs, medication, trauma/domestic violence) and whether they had experienced 10 different barriers to receiving mental health or substance user treat- ment (e.g., lack of money for treatment, lack of transporta- tion to treatment, fear of negative consequences related to treatment). Results showed no differences by gender in

- 8. readiness for treatment (as measured by a 3-point readi- ness for treatment scale) or barriers to obtaining treatment. Females reported a great number of service needs overall, as well as more needs for treatment related to family and trauma issues. Overall, this literature suggests that there are some ways that males and females with SMI and SUD appear similar (patterns of substance use, self-reported barriers to care) and some ways in which they are different (drug of choice, consequences of use). However, several questions related to gender differences in individuals with SMI and SUDs remain. First, the literature on gender and substance use in SMI is relatively small. Further comparisons of pat- terns and severity of substance use in SMI can help to establish whether similarities found in previous research are consistent across samples. Second, gender differences in variables such as motivation to change and reasons for seeking treatment, which might impact treatment engage- ment and outcome, have not been explored in dually di- agnosed individuals in a comprehensive way. Third, it is unclear whether gender differences are more or less pro- nounced in individuals seeking substance use treatment versus those in the community who are not seeking help for substance abuse. The studies of gender differences reviewed above have been conducted with samples of individuals in treatment. Whether gender differences ex- ist in community samples that are not seeking treatment is not known. Dually diagnosed men and women in the community may show differences in substance use and severity; these differences may attenuate, as individuals of both genders move into severer use and acknowledge that they need to seek treatment. That is, by the time treat- ment is initiated men and women may appear similar, but in the community prior to seeking treatment, they may

- 9. have been quite different. Such questions are important as we think about whether women have unique treatment needs and whether and how to structure treatment to meet them. The present study sought to address each of these is- sues. First, we explored gender differences in patterns and consequences of SUDs, in order to determine if pre- vious findings in non-SMI samples are relevant to indi- viduals with SMI. Second, we examined potential gender differences in two previously underexplored but clinically important areas: reasons for seeking treatment and moti- vation to change. Exploration of these domains will al- low for a first descriptive look at how women with dual SMI and SUDs come to treatment and what they hope to get from it-—both important issues that need to be exam- ined in order to better attract this group of substance users into services. Third, we examined gender differences in two different samples: a community sample that was not seeking substance use treatment and a treatment-seeking sample of clients at community mental health center that agreed to participate in a study of an intervention for sub- stance use designed for people with SMI. While these samples are not balanced and so findings cannot be com- pared across them, their use here provides the opportunity to look descriptively at the ways in which gender differ- ences may be manifested in different cohorts of individ- uals with dual disorders and to identify any differences in non-treatment-seeking and treatment-seeking samples that may inform service use and development. Specifi- cally, we examined gender differences in (1) psychiatric diagnosis and symptoms, (2) patterns and severity of sub- stance use, (3) consequences of substance use, (4) moti- vation to change, and (5) reasons for seeking treatment. METHOD

- 10. Participants We used data from two studies of SMI and SUDs (see Nidecker, DiClemente, Bennett, & Bellack, 2008) for 810 A. DRAPALSKI ET AL. a description of the community sample and Bellack, Bennett, Gearon, Brown, & Yang (2006) for a descrip- tion of the treatment-seeking sample). Briefly, Study 1 in- volved a survey of substance use and motivation to change in nontreatment-seeking individuals with SMI and either current cocaine dependence or cocaine dependence in re- mission recruited from a Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center and two community clinics in Baltimore, Mary- land and assessed five times over 12 months (The Pro- cess of Change in Drug Abuse by Schizophrenics, funded by NIDA, A. Bellack, PI, n = 240 subjects, “community” sample). The present study included data from partici- pants with current cocaine dependence (n = 137) because of our interest in describing gender differences among in- dividuals with current SUDs. This sample of participants with current cocaine dependence was 59.9% male, 77.4% African American, 19% White, and 3.6% other, had a mean age of 42.4 (SD = 7.6; range 22–64) and a mean of 11.9 years of education (SD = 2.1; range = 5–18). In terms of diagnosis, 55% of participants in the com- munity sample had a primary diagnosis of schizophre- nia or schizoaffective disorder, 45% mood or affective disorder, and 2% other diagnoses. Participants reported a mean (SD) of 6.3 (9.64) years of heroin use, 13.1 (8.05) years of cocaine use, 11.31 (11.62) years of cannabis use, and 12.27 (10.22) years of polydrug use. Study 2 was a randomized trial of a behavioral intervention for

- 11. substance abuse in a treatment-seeking sample of peo- ple with SMI (Behavioral Treatment & Substance Abuse in Schizophrenia, funded by NIDA, A. Bellack, PI, n = 175, “treatment-seeking” sample). Participants with cur- rent cocaine, heroin, and/or marijuana dependence were recruited from outpatient community clinics and a VA medical center in Maryland. This sample was 63.4% male, 75.4% African American, and 22.3% White and had a mean age of 42.7 (SD = 7.10; range 21–57) and a mean of 11.2 years of education (SD = 2.28; range 3–18). In terms of diagnosis, 55% of participants in the treatment- seeking sample had a primary diagnosis of mood or affec- tive disorder, 38% schizophrenia or schizoaffective dis- order, and 7% other diagnoses. Cocaine was the most frequently abused drug (69%), followed by opiates (25%) and cannabis (7%). Participants reported a mean (SD) of 5.73 (8.76) years of heroin use, 10.2 (8.21) years of co- caine use, 10.2 (10.4) years of cannabis use, and 12.1 (10.7) years of polydrug use. Measures Diagnostic and Symptom Assessments The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID–I; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & William, 1994) was used to es- tablish diagnosis. Interviews were completed by doctoral- or masters-level psychologists. Diagnoses were achieved utilizing all available information (patient report, med- ical records, treatment providers). Interrater reliability (kappa) for the SCID diagnoses (psychiatric and sub- stance abuse/dependence) was greater than 0.80. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS; Opler, Kay, Lindenmayer, & Fiszbein, 1992) was used to as- sess symptoms of psychiatric illness, with separate ratings for positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and general psychopathology. The PANSS has good reliability and va-

- 12. lidity (Kay, Fiszbein, & Opler, 1987). Substance Use and Treatment Utilization The Addiction Severity Index (ASI; McLellan et al., 1992) was used at baseline to assess drug use frequency and severity. We administered the drug, alcohol, family/social, and legal sections of the ASI, as they are the most reli- able sections for this population (Carey, Coco, & Correia, 1997). The Substance Use Event Survey for Severe Men- tal Illness (SUESS; Bennett, Bellack, and Gearon, 2006) is a relatively brief (20–30 minutes) measure that assesses clinical issues and service utilization in individuals with SMI and SUDs. The SUESS contains two types of items: (1) items related to service use and (2) items to gather descriptive information that may relate to service use in clients with SMI. The SUESS also gathers information about reasons for starting substance use treatment. Psy- chometric properties and validity of the SUESS are good (Bennett et al., 2006). Motivation to Change Stage of change was assessed with the University of Rhode Island Change Assessment—Maryland (URICA- M; Nidecker, DiClemente, Bennett, & Bellack, 2008). The original URICA is a 32-item self-report question- naire, which employs a 5-point Likert scale asking respondents to rate their degree of agreement (or disagree- ment) with each item (DiClemente & Hughes, 1990). Each item refers to a “problem” that the patient identi- fies. The URICA-M is a modified version designed to suit the needs of people with SMI. A single readiness to change score is calculated by subtracting the precon- templation score from the sum of the contemplation, ac- tion, and maintenance scores (Carbonari, DiClemente, & Zweben, 1994). The possible range of the readiness score is −2.00–14.00 with higher scores representing greater

- 13. motivation to change. Participants also completed the Temptation to Use Drugs Scale and the Abstinence Self- Efficacy Scale (DiClemente, Carbonari, Montgomery, & Hughes, 1994), 20-item scales that assess the degree to which subjects feel “tempted” to use drugs in different situations and the degree to which they feel confident in their ability to abstain from drug use in those situations. Respondents made ratings using 5-point Likert scales, and a total score was calculated. The Process of Change Questionnaire (POC; Prochaska, Velicer, DiClemente, & Fava, 1988) was used to assess the frequency of occur- rence of 10 core processes used to attain the desired be- havioral change on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never to 5 = repeatedly). From this, we calculated a total process score (using all 20 items), an experiential process subscore (10 items), and a behavioral process subscore (10 items). Experiential processes involve more covert cog- nitive and behavioral processes such as consciousness raising (greater awareness of the problem behavior) and dramatic relief (emotions associated with the problem be- havior or solution to the problem are aroused). Behavioral processes involve more overt, observable processes such GENDER DIFFERENCES IN SUD AND SMI 811 TABLE 1. Diagnostic and symptom features of a treatment- seeking and nontreatment-seeking sample of people with SMI and SUD by gender Treatment-seeking Community Male (n = 111) Female (n = 64) Male (n = 82) Female (n = 55) Overall MANOVA F (4, 158) = 0.18, p = .95 F (4, 132) = 1.21,

- 14. p = .31 Mean positive symptoms (SD) 1.8 (0.7) 1.9 (0.6) 2.0 (0.7) 2.1 (0.9) Mean negative symptoms (SD) 1.8 (0.6) 1.8 (0.6) 2.0 (0.7) 2.1 (0.8) Mean general symptoms (SD) 1.9 (0.4) 1.8 (0.4) 1.9 (0.4) 2.0 (0.6) Percent affective diagnosis (n) 53% (59) 58% (37) 42% (34) 51% (28) Percent schizophrenia spectrum diagnosis (n) 40% (44) 36% (23) 56% (46) 47% (26) as contingency management (positive behavioral changes are rewarded) and stimulus control (planned strategies for coping with or avoiding triggers). Psychometric prop- erties of these scales are strong across addictive behav- iors (DiClemente et al., 1994; Hiller, Broome, Knight, & Simpson, 2000). Procedures For both studies, all procedures were approved by the Uni- versity of Maryland Institutional Review Board. Medical records of all new intakes at several recruitment sites (a VA medical center and two community clinics in Mary- land) were reviewed once per week to determine pre- liminary eligibility, including diagnosis of SMI. All po- tential subjects participated in a standardized informed consent process with trained recruiters and were advised at the time that a Federal Certificate of Confidentiality would protect the information they provided. For both studies, participants completed the diagnostic interview and symptom assessment first and generally completed the remaining baseline assessments within a week. Also in both studies, participants subsequently completed self-

- 15. report interviews regarding their substance use and pro- vided urine samples for drug screens at follow-up time points. Data Analysis Separate multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVAs) were used to examine gender differences in symptoms and diagnosis, frequency and severity of substance use, and motivation to change for each sample (treatment- seeking and community). Chi-square tests were used to determine differences in history of trauma/victimization, medical problems, and probation/parole status between men and women in each sample and reasons for seek- ing substance use treatment in the treatment-seeking sam- ple. T-tests were used to examine gender differences in lifetime arrests, lifetime charges, and days incarcerated in the past month. Owing to differences in inclusion crite- ria between the community and treatment-seeking sam- ples, direct comparisons of the two samples were not done. RESULTS Differences in Psychiatric Diagnosis and Symptoms by Gender Table 1 lists diagnostic breakdown and PANSS scores by gender for both samples. MANOVA was used to as- sess gender differences in symptoms and diagnosis. The MANOVA was not significant for either sample. Psychi- atric symptoms fell within the mild to moderate range for both samples. Frequency and Severity of Substance Use by Gender Separate MANOVAs were conducted to examine gender differences in the frequency and severity of substance use. Frequency was measured by four ASI items tap-

- 16. ping drug and alcohol use in the last 30 days (number of days of cocaine use, heroin use, marijuana use, and alcohol use). Severity was assessed with six additional variables by using ASI items: number of days of drink- ing in the past month, number of days of drinking-related problems in the last month, number of days that more than one substance was used in the last month, number of days of drug-related problems in the last month, the degree of self-reported distress from drug-related prob- lems in the last month, and the degree of self-reported dis- tress from alcohol-related problems in the last month. A seventh variable was constructed that assessed the num- ber of different substances the participant had used in the past month. Results for both samples are presented in Table 2. Overall, there were no differences in last- month frequency or severity of substance use in either sample. Gender Differences in Victimization, Medical Problems, and Legal Problems Next, we examined gender differences in victimization, medical problems, and legal problems (Table 3). First, victimization was examined using three items from the ASI that assess lifetime incidence of emotional, physi- cal, and sexual abuse. Rates of victimization were high, with over 70% of participants in both samples report- ing emotional abuse, between 48% and 50% of the sam- ples reporting physical abuse, and from one-quarter (com- munity) to one-third (treatment-seeking) of participants reporting a history of sexual abuse. Women in both 812 A. DRAPALSKI ET AL. TABLE 2. Patterns and severity of substance use of a treatment-

- 17. seeking and nontreatment-seeking sample of people with SMI and SUD by gender Treatment-seeking Community Male (n = 111) Female (n = 64) Male (n = 82) Female (n = 55) Pattern of substance use (past month) [mean (SD)] Overall MANOVA F (4, 170) = 1.37, p = ns F (4, 129) = 1.85, p = ns Days cocaine use 3.3 (5.6) 4.8 (7.1) 5.7 (6.4) 6.5 (9.2) Days heroin use 1.2 (4.2) 2.8 (7.6) 1.7 (4.6) 1.7 (6.0) Days marijuana use 1.2 (4.8) 2.0 (6.3) 0.7 (1.9) 1.4 (4.8) Days alcohol use 3.2 (6.6) 3.3 (6.1) 6.4 (9.1) 3.8 (6.8) Severity of substance use (past month) [mean (SD)] Overall MANOVA F (7, 164) = 1.39, p = .213 F (7, 125) = 1.83, p = .087 Days drug use 2.1 (4.7) 3.0 (5.2) 3.7 (6.0) 4.0 (7.3) Number of substances used 1.3 (1.3) 1.5 (1.3) 2.2 (1.2) 1.9 (1.3) Days drug problems 7.4 (10.3) 12.6 (12.3) 8.8 (11.4) 10.2 (12.5) Distress from drug problems 1.9 (1.5) 2.4 (1.5) 2.2 (1.6) 2.1 (1.6) Days alcohol use 3.2 (6.6) 3.3 (6.1) 6.4 (9.1) 3.8 (6.8) Days alcohol problems 2.8 (6.6) 3.1 (7.7) 4.1 (9.0) 1.6 (4.7) Distress from alcohol problems 0.9 (1.4) 0.7 (1.2) 1.1 (1.5) 0.5 (1.0) samples were more likely than men to report a history of sexual abuse (community: χ 2 = 3.88, p = .049; treatment- seeking: χ 2 = 13.4, p < .001). There were no gender differences in physical or emotional abuse. Violent victimization was assessed with a separate variable constructed using five items from the SUESS reflecting whether or not the respondent had been a victim of a vi-

- 18. olent crime (i.e., robbed or mugged, beaten up or physi- cally injured, raped or sexually assaulted, life-threatening assault, any other life-threatening events, or serious in- jury) in the 90 days prior to the assessment. Men and women did not differ on this variable (community: χ 2 = .04, p = ns; treatment-seeking: χ 2 = 1.81, p = ns). Second, medical problems were assessed with two items from the SUESS: self-report of a physical/medical prob- lem in the last 90 days and met with a doctor or nurse about a medical problem in the last 90 days. There were no gender differences on these variables in ei- ther sample. Third, four legal variables from the ASI were compared: current probation/parole, number of lifetime arrests, number of lifetime incarcerations, and number of days incarcerated in the last month. In the treatment-seeking sample, men reported more crimi- nal charges [Z (136) = −2.00, p = .045] and con- victions [Z (136) = −2.11, p = .035] than women. There were no gender differences in criminal charges or convictions in the community sample [t (174) = 1.76, p = ns]. There were no gender differences in pro- bation/parole status or number of days in the jail/prison in either sample. TABLE 3. Gender differences in victimization, medical problems, and legal problems in a treatment-seeking and nontreatment-seeking sample of people with SMI and SUD Treatment-seeking Community Variable Male (n = 111) Female (n = 64) Male (n = 82) Female (n = 55) History of trauma/victimization

- 19. Percent emotional abuse, lifetime (n) 73% (81) 83% (53) 74% (60) 72% (39) Percent physical abuse, lifetime (n) 45% (50) 59% (38) 42% (34) 57% (30) Percent sexual abuse, lifetime (n) 24% (27) 52% (33)∗ ∗ 21% (17) 37%(19)∗ Percent violent victimization, past 90 days (n) 24% (27) 34% (21) 33% (27) 35% (19) Medical problems (past 90 days) Percent reported physical/medical problems (n) 67% (74) 63% (39) 56% (46) 46% (25) Percent met with doctor/nurse (n) 77% (57) 90% (35) 76% (35) 84% (21) Legal problems Number on probation/parole (%) 24 (27%) 19 (12%) 24 (19%) 11 (6%) Mean number lifetime arrests/charges (SD) 6.3 (9.4) 3.7 (5.0)∗ 5.1 (7.5) 3.4 (3.8) Mean number lifetime convictions (SD) 3.9 (7.4) 2.1 (4.0)∗ 2.6 (4.9) 1.5 (2.3) Mean days incarcerated past month (SD) 8.1 (16.1) 4.9 (11.0) 2.0 (8.9) 0.6 (4.1) ∗ Females and males differ, p < .05. ∗ ∗ Females and males differ, p = .001. GENDER DIFFERENCES IN SUD AND SMI 813 TABLE 4. Gender comparisons in motivation to change in a treatment-seeking and nontreatment-seeking sample of people

- 20. with SMI and SUD Treatment-seeking Community Male (n = 111) Female (n = 64) F p Male (n = 82) Female (n = 55) F p Overall MANOVA F (5, 165) = 3.07, p = .01 F (5, 130) = 0.45, p = .81 Mean temptation to use drugs (SD) 2.7(0.9) 3.1(1.0) 7.49 .007 3.1(0.9) 3.0(1.0) 0.35 .557 Mean experiential process (SD) 3.3(0.7) 3.6(0.7) 4.26 .040 3.2(0.7) 3.1(0.8) 0.17 .678 Mean behavioral process (SD) 3.4(0.8) 3.5(0.9) 0.70 .403 3.3(0.7) 3.3(0.9) 0.07 .793 Mean readiness to change (SD) 10.2(1.6) 10.9(1.7) 7.95 .005 10.0(1.9) 9.9(2.0) 0.04 .835 Mean drug self-efficacy (SD) 3.2(0.9) 2.9(1.1) 2.93 .089 3.0(0.9) 2.8(1.0) 0.71 .401 Motivation to Change A one-way MANOVA was used to assess gender differ- ences in variables tapping motivation to change (temp- tation to use drugs, experiential process of change, behavioral processes of change, readiness to change, and drug self-efficacy). The overall MANOVA was significant

- 21. [F (5, 165) = 3.07, p = .01]. Separate one-way analy- ses of variance (ANOVAs; Table 4) showed that, in the treatment-seeking sample, women reported greater temp- tation to use drugs, greater use of experiential processes of change, and greater overall readiness to change than men. There were no gender differences in motivation to change in the community sample. Reasons for Seeking Treatment We then explored gender differences in reasons for seek- ing treatment in the treatment-seeking sample (Table 5). Participants reported a number of reasons for seeking treatment. Thinking seriously about the pros and cons of using drugs was the most frequently cited reason for seeking treatment (83%), followed by worsening of psychological or emotional problems (79%), experienc- ing a major change in lifestyle (72%), experiencing a recent traumatic event (61%), and hitting rock bottom (60%). Gender differences in responses were explored via chi-square analyses. There were no significant gender differences. DISCUSSION This study sought to describe the ways in which sub- stance use and severity, motivation to change, and rea- sons for seeking treatment differed between women and men with SMI and SUDs. Data were collected from two samples of participants with SMI and SUDs: a com- munity sample and a sample seeking treatment for sub- stance abuse. In line with previous research on gen- der differences in dually diagnosed individuals, women and men in both samples showed more similarities than differences in terms of their patterns and severity of substance use. Alcohol and cocaine were the most fre- quently used substances for both men and women, and

- 22. there were no gender differences in severity of substance use. Because all participants in the community sample met criteria for current cocaine dependence, it is not surprising that there were no gender differences in co- caine use or problems from cocaine use. However, no such restriction was in place for the treatment-seeking sample. The fact that women showed similar substance use and severity to men contrasts with findings in pri- mary substance users. Men with primary SUDs typi- cally evidence more problems with alcohol and mar- ijuana use and women more problems with cocaine use (Pelissier & Jones, 2005). The similarity of women and men with SMI and SUDs in the treatment-seeking TABLE 5. Reasons for seeking treatment by gender in a treatment-seeking samplea (in %) Variable Total (n = 77) Male (n = 47) Female (n = 30) Thought seriously about pros and cons of use 83.3 82.2 85.2 Psychological or emotional problems worsened 78.7 75.7 83.3 Major change in lifestyle 72.2 71.1 74.1 Experienced a traumatic or very disturbing event 61.1 62.2 59.3 Hit “rock bottom” 59.7 64.4 51.9 Referred by case manager or therapist 47.3 46.7 48.1 Warned about use by family or close other 41.7 40.0 44.4 Doctor warned you about use 41.7 42.2 40.7 Physical health problems 40.3 42.2 37.0 Someone else quit using or cut down 29.2 28.9 29.6 Religious experience 27.8 28.9 25.9 Saw someone else high 20.8 17.8 25.9 Referred by court/probation/parole officer 15.3 15.6 14.8 aAll chi-square analyses were not significant.

- 23. 814 A. DRAPALSKI ET AL. sample in terms of frequency and severity of substance use may be related in part to symptoms of SMI, which may render both men and women equally vulnerable to using substances and the negative impact of substance use on functioning. Gender differences were found in rates of some substance-related negative consequences. First, women in both the treatment-seeking and the community samples were more likely to report sexual abuse than men, a find- ing that is in line with other studies (Alexander, 1996; Brunette & Drake, 1998; Gearon, Kaltman, Brown, & Bellack, 2003; Gearon, Nidecker, et al., 2003). The fact that this gender difference was found in both samples il- lustrates the pervasiveness of sexual abuse among women with SMI and SUDs and highlights trauma as an issue that impacts women regardless of their substance abuse treatment status. Higher rates of sexual abuse were found among treatment-seeking women compared with women in the community, suggesting that abuse or trauma may play a role in the initiation of treatment. Interestingly, al- most a quarter of men reported prior sexual abuse. There were high rates of physical abuse, emotional abuse, or violent victimization overall and no gender differences in these domains in either sample, suggesting a unique risk for women in terms of sexual abuse. Second, men in the treatment-seeking sample were more likely to have legal problems than women, including criminal charges and convictions. This may reflect gender differences in how drugs are accessed and the settings in which drugs are used by people with SMI or the nature of the crimes committed and/or likelihood of being prosecuted for those crimes. Gearon, Nidecker and colleagues (2003) found that women with SMI were more likely to purchase drugs

- 24. from, use drugs with, and get money for drugs from friends and significant others. This close association be- tween drug use and family may result in women with SMI being less likely to use substances in situations that may place them at risk for legal difficulties (i.e., using in pub- lic places, attempting to purchase drugs from drug dealers, using drugs with strangers). The fact that this difference was found only in the treatment-seeking sample suggests that increasing legal problems may be a factor that propels men with SMI and SUDs into treatment. Third, medical problems were equally prevalent among men and women in both samples. A lack of gender differences in medical problems could reflect the high rate of medical problems among people with SMI in general and particularly among those with comorbid SUDs. Readiness to change variables and reasons for seeking treatment were of particular interest in this study. Women in the treatment-seeking sample reported greater temp- tation to use drugs, greater use of experiential processes of change, and greater overall readiness to change than men. This pattern suggests that women come to treatment with greater readiness to attempt change than men and may have already made some change efforts. This find- ing is in line with others that have found that women with dual diagnoses use more experiential processes as part of their change efforts than men (O’Conner, Carbonari, & DiClemente, 1996). Use of experiential processes is as- sociated with preparing for change (DiClemente et al., 1991). The combination of higher experiential process and readiness to change scores among women could mean that women are more likely to seek treatment once they have committed to change. In contrast, men may begin treat- ment less convinced of the benefits of change and less likely to have attempted change on their own (Watkins

- 25. et al., 1999). Interestingly, despite the fact that all partic- ipants in the community sample met criteria for current cocaine dependence, no gender differences were found in motivation to change. This suggests that there is likely some factor other than simply drug use severity that im- pacts women’s motivation and treatment seeking. As we have speculated, it is possible that trauma may play a role here, as rates of trauma were higher among women in the treatment-seeking sample. Men and women reported similar reasons for seeking substance abuse treatment. Engaging in an evaluation of the advantages and disadvantages of substance use was the most frequently endorsed reason for seeking treat- ment. An increase in psychological health problems, hav- ing a major change in lifestyle, and recently experiencing a traumatic event were also frequently identified as rea- sons for seeking treatment. The lack of gender differences here suggests that there may be a core set of reasons for seeking treatment in people with SMI and SUD. Factors such as mental health problems and trauma may be among the most important experiences that convince people with SMI and SUDs to enter substance abuse treatment, regard- less of gender. These findings have implications for the identification and clinical care of men and women with SMI and SUDs. The high rates of abuse found here and in other stud- ies suggest that trauma and its relationship to substance use should to be assessed as a routine part of substance abuse treatment for both men and women. Given that sex- ual trauma is particularly prevalent among women with SMI and SUDs, substance abuse treatment for women with dual disorders may need to include strategies specif- ically focused on reducing risk of abuse and coping with trauma. Inclusion of these strategies could serve to

- 26. reduce incidence of trauma, minimize the impact of trauma, and improve treatment engagement, retention, and outcome (Bellack & Gearon, 1998). Moreover, as- sessment of trauma by health care professionals in the community, such as workers in primary care, outpatient mental health, or emergency rooms, might be an impor- tant step in getting women with SMI and SUD in the com- munity to think about the harm caused by their substance use and perhaps consider treatment for it. In addition, our findings suggest that when women with SMI and SUDs do come to treatment, they are more highly motivated than men to make a change and may already be engaging in change efforts. This suggests that the initial activities as- sociated with treatment should involve assessment of mo- tivation and tailoring, depending on a woman’s level of readiness to change. Women who are already involved in change may want different sorts of advice, assistance, or GENDER DIFFERENCES IN SUD AND SMI 815 support from a clinician than others who are less ready or who may be still deciding whether and how to make a change. Study’s Limitations Several limitations of this study should be noted. Individu- als in the treatment-seeking sample were selected because they reported current dependence on at least one of sev- eral drugs (cocaine, heroin, or marijuana), while those in the community sample were selected for current depen- dence on cocaine only (although they could meet criteria for dependence on other drugs in addition to cocaine). Be- cause of these differences, we were unable to directly ex- amine gender differences across samples. A direct com-

- 27. parison of gender differences in treatment-seeking and nontreatment-seeking people with SMI and SUD could provide important information concerning factors that fa- cilitate or impede treatment seeking in this group. In ad- dition, the studies from which these data were taken were not designed to assess gender differences and so may not have captured relevant variables. For example, the list of reasons for seeking treatment used here was de- signed for substance users regardless of gender and so did not include reasons that may be especially relevant for women such as reasons related to child custody, interac- tions with child protective services, and housing issues. Future research should include these sorts of reasons for seeking treatment that might be especially important to women. While these findings provide a useful first step, more remains to be examined and understood about women with SMI and SUDs. Future studies should move be- yond patterns and consequences of use and directly assess whether women with SMI and SUDs experience unique barriers to treatment. People with SMI and SUDs have reported numerous barriers to treatment, including cost of treatment, fears about what happens in treatment, and about being hospitalized (Nidecker, Bennett, Gjonbalaj- Marovic, RachBeisel, & Bellack, 2009). It remains un- clear if women experience additional barriers such as family-related responsibilities including care of children or other family members and fear about how treatment may impact important social and family relationships. In addition, our finding that women may be more ready to change and may have attempted some behavior change prior to seeking treatment needs to be understood in light of other findings that women with SMI and SUDs are less likely to seek formal treatment than men (Alexander, 1996; Bellack & Gearon, 1998; Comtois & Ries, 1995).

- 28. Women may attempt more change on their own, seeking out professional assistance only when their change efforts have failed. Thus, motivation and change efforts may ac- tually serve as a barrier to formal care for some women who believe they can change on their own. A better un- derstanding of the factors that keep women away from treatment could lead to the development of relevant and effective outreach and treatment approaches that address or overcome barriers to care for women with SMI and SUDs. Declaration of Interest The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the writing and content of the article. RÉSUMÉ Différences dans les modèles et conséquences de la dépendance aux substances, dans la recherche de traitements et dans la motivation de vouloir changer selon les sexes Différences dans les modèles et conséquences de la dépendance aux substances, dans la recherche de traite- ments et dans la motivation de vouloir changer selon les sexes. Deux échantillons ont été examines: un échantillon comprenait des gens avec des maladies mentales graves et l’autre échantillon comprenait des gens avec des troubles liés à l’usage de substances. Un des échantillons compre- nait des gens dans la communauté qui ne recherchaient pas présentement de traitements pour la dépendance aux sub- stances (N = 175) et l’autre échantillon comprenait des gens qui recherchaient un traitement (N = 137). Dans les

- 29. deux groupes, les femmes et les hommes ont démontrées plus de similarités que de différences dans les modèles et sévérité d’utilisation de leurs substances. Par contre, les femmes qui recherchaient un traitement ont démontrées une facilité plus importante à changer leurs dépendances aux substances. Les problèmes de maladies mentales et les expériences traumatiques pourraient faire en sorte que les gens faisant partie de ses deux groupes sont incites à entrer dans un traitement d’abus de substances indépendamment de leur sexe. RESUMEN Diferencias de género de su uso de sustancia, con- secuencias, el motivo para cambiar, y buscando- tratamiento en personas con trastornos mentales crónico/grave Diferencias de género en pautas y consecuencias del uso de sustancia, buscando-tratamiento, y el motivo para cam- biar fueron examinado en dos muestras de personas con trastornos mentales crónico/grave (TMC) y comorbilidad de trastornos por uso de sustancias (TUS): una muestra de la comunidad cual presentemente no está buscando tratamiento de abuso de sustancia (N = 175) y una mues- tra buscando tratamiento (N = 137). En ambos grupos, las mujeres y los hombres demostraron más similitudes que diferencias en la pauta y la severidad de su uso de sus- tancia. Sin embargo, mujeres cual buscaron-tratamiento mostraron la prontitud más grande para cambiar su uso de sustancia. Los problemas de la salud mental y experi- encias traumáticas pueden incitar a personas con TMC y 816 A. DRAPALSKI ET AL.

- 30. TUS a entrar tratamiento de abuso de sustancia, a pesar de género. THE AUTHORS Amy Drapalski, Ph.D., is Administrative Core Manager at the Veterans Affairs (VA) Capital Health Care Network Mental Illness, Research, Education and Clinical Center (MIRECC). Her research has primarily focused on identifying barriers and facilitators of recovery and developing, evaluating, and implementing psychosocial treatments for individuals with serious mental illness and their families. Her current research is aimed at understanding the impact of self-stigma and other related factors on recovery and developing interventions aimed at reducing internalized stigma and its effects in people with serious mental illness. Melanie Bennett, Ph.D., is a Clinical Associate Professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Maryland, School of Medicine. Her primary research focus has been on the assessment and treatment of substance use disorders in people with serious

- 31. mental illness. Her current research focuses on developing behavioral treatment programs to alcohol, drug, and nicotine dependence in people with schizophrenia and other forms of serious mental illness. She is also interested in ways to improve treatment engagement and outcome via motivational enhancement strategies that are adapted for individuals with serious mental illness. Alan S. Bellack, Ph.D., A.B.P.P., received his Ph.D. from the Pennsylvania State University in 1970. He currently is Professor of Psychiatry and Director of the Division of Psychology at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and Director of the VA Capital Health Care Network Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center (MIRECC). He was formerly Professor of Psychiatry and Director of Psychology at the Medical College of Pennsylvania and Professor of Psychology and Director of Clinical Training at the University of Pittsburgh. He is a Past President of the Association for Advancement of Behavior Therapy and of the Society for a Science of Clinical Psychology. He is a Diplomate of the American Board of Behavior Therapy and the American Board of Professional Psychology and a fellow of the American Psychological Association, the American Psychological Society, the Association for Clinical Psychosocial Research, and the American Psychopathological Association. He was the first recipient of the American Psychological Foundation Gralnick Foundation Award for his lifetime research on

- 32. psychosocial aspects of schizophrenia and was the first recipient of the Ireland Investigator Award from NARSAD. He received an National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) MERIT award and has had continuous funding from NIH since 1974 for his work on schizophrenia, depression, social skills training, and substance abuse. He chaired the VA Recovery Transformation Workgroup and is Chair of the VA National Recovery Advisory Committee. He is founding Coeditor of the journals Clinical Psychology Review and Behavior Modification and serves on a number of other editorial boards and a VA Merit review study section. Dr. Bellack has published 175 journal articles and 52 book chapters. He is Coauthor or Coeditor of 31 books, including Bellack, A. S., Mueser, K. T., Gingerich, S., & Agresta, J. (2004). Social Skills Training for Schizophrenia: A Step-by- Step Guide (Second Edition). New York: Guilford Press, and Bellack, A. S., Bennett, M. E., & Gearon, J. S. (2007). Behavioral Treatment for Substance Abuse in People With Serious and Persistent Mental Illness. New York: Taylor and Francis. GLOSSARY Behavioral Processes of Change: More overt, observable

- 33. processes (i.e., reinforcement management, helping re- lationships, stimulus control, etc.) by which behavior change may occur. Dual Diagnosis or Co-Occurring Substance Disorder: having both a psychiatric condition or illness and a sub- stance use disorder. Experiential Processes of Change: More covert cognitive, and behavioral processes (i.e., increasing awareness of a problem behavior, assessing the impact of behav- ior on the surrounding environment, self-reevaluation, etc.) by which behavior change may occur. Stages of Change: A key construct in the Transtheoretical Model of Change (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983) re- ferring to the stages through which an individual pro- gresses when making a behavior change; stages in- clude precontemplation (not thinking about/planning to change in the near future), contemplation (aware- ness of a desire to change in the near future), prepa- ration (plans made to change in the near future), action (changes in behavior occur), and maintenance (behav- ior change has occurred and has been maintained for a least 6 months). REFERENCES Alexander, M. J. (1996). Women with co-occurring addictive and mental disorders: An emerging profile of vulnerability. Ameri- can Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 66, 61–70. Angermeyer, M. C., Kuhn, L., & Goldstein, J. M. (1990). Gender and the course of schizophrenia: Differences in treatment out-

- 34. comes. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 16, 293–307. GENDER DIFFERENCES IN SUD AND SMI 817 Bellack, A. S., Bennett, M. E., Gearon, J. S., Brown, C. H., & Yang, Y. (2006). A randomized clinical trial of a new behavioral in- tervention for drug abuse in people with severe and persistent mental illness. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63, 426–432. Bellack, A. S., & Gearon, J. S. (1998). Substance abuse treat- ment for people with schizophrenia. Addictive Behaviors, 23(6), 749–766. Bennett, M. D., Bellack, A. S., & Gearon, J. S. (2006). Development of a comprehensive measure to assess clinical issues in dually diagnosed patients: The substance use event survey for severe mental illness. Addictive Behavior, 31(12), 2249–2267. Brunette, M. F., & Drake, R. E. (1997). Gender differences in pa- tient with schizophrenia and substance abuse. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 38, 109–116. Brunette, M. F., & Drake, R. E. (1998). Gender differences in home- less person with schizophrenia and substance abuse. Community Mental Health Journal, 34, 627–642. Carbonari, J. P., DiClemente, C. C., & Zweben, A. (1994). A readi- ness to change measure. Paper presented at the AABT National Meeting in San Diego, CA.

- 35. Carey, K. B., Coco, K. M., & Correia, C. J. (1997). Reliabil- ity and validity of the Addiction Severity Index among outpa- tients with severe mental illness. Psychological Assessment, 9, 422–428. Childers, S. E., & Harding, C. M. (1990). Gender, premorbid social functioning, and long-term outcomes in DSM-III schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 16, 309–318. Comtois, K. A., & Ries, R. (1995). Sex difference in dually diag- nosed severely mentally ill clients in dual diagnosis outpatient treatment. American Journal of Addictions, 4, 245–253. DiClemente, C., & Hughes, S. O. (1990). Stages of change pro- files in alcoholism treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse, 2, 217–235. DiClemente, C. C., Carbonari, J. P., Montgomery, R. P. G., & Hughes, S. O. (1994). The Alcohol Abstinence Self-Efficacy Scale. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 55, 141–148. DiClemente, C. C., Prochaska, J. O., Fairhurst, S. K., Velicer, W. F., Velasquez, M. M., & Rossi, J. S. (1991). The process of smoking cessation: an analysis of precontemplation, contemplation, and preparation stages of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59, 295–304. First, M. B., Spitzer, R. L., Gibbon, M., & William, J. B. W. (1994). Structured clinical interview of axis I DSM-IV. New York, NY: Biometrics Research Department, New State Psychiatric

- 36. Institute. Frye, M. A., Altshuler, L. L., McElroy, S. L., Suppes, T., Keck, P. E., Denicoff, K., et al. (2003). Gender differences in prevalence, risk, and clinical correlates of alcoholism comorbidity in bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160, 883–889. Gearon, J. S., & Bellack, A. B. (1999). Sex differences in illness pre- sentation, course, and level of functioning in substance-abusing schizophrenia patients. Schizophrenia Research, 43, 65–70. Gearon, J. S., Kaltman, S. I., Brown, C., & Bellack, A. S. (2003). Traumatic Life Events and PTSD among women with sub- stance use disorders and schizophrenia. PsychiatricServices, 54, 523–528. Gearon, J. S., Nidecker, M., Bellack, A., & Bennett, M. (2003). Gender difference in drug use behavior in people with seri- ous mental illnesses. The American Journal on Addictions, 12, 229–241. Greenfield, S. F., Brooks, A. J., Gordon, S. M., Green, C. A., Kropp, F., McHugh, R. K., et al. (2007). Substance abuse treatment en- try, retention, and outcome in women: a review of the literature. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 86, 1–21. Grella, C. E. (2003). Effects of gender and diagnosis on ad- diction history, treatment utilization, and psychosocial func- tioning among a dually-diagnosed sample in drug treat- ment. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 35(Suppl. 1), 169–

- 37. 179. Hiller, M. L., Broome, K. M., Knight, K., & Simpson, D. D. (2000). Measuring self- efficacy among drug-involved proba- tioners. Psychological Reports, 86, 529–538. Kawa, I., Carter, J. D., Joyce, P. R., Doughty, C. J., Frampton, C. M., Wells, J. E., et al. (2005). Gender differences in bipolar disorder: Age of onset, course, comorbidity, and symptom presentation. Bipolar Disorder, 792, 119–125. Kay, S. R., Fiszbein, A., & Opler, L. A. (1987). The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for patients. Psychiatric Re- search, 43, 223–230. Kennedy, N., Boydell, J., Kalidindi, S., Fearon, P., Jones, P. B., van Os, J., et al. (2005). Gender differences in incidence and age at onset of mania and bipolar disorder over a 35-year period in camberwell, England. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162, 257–262. Kessing, L. V. (2004). Gender differences in the phenomenology of bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorder, 6(5), 421–425. McGlashan, T. H., & Bardenstein, K. K. (1990). Gender differ- ences in affective, schizoaffective, and schizophrenic disorder. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 16(2), 319–329. McLellan, A. T., Kushner, H., Metzger, D., Peters, R., Smith, I., Grissom, G., et al. (1992). The fifth edition of The Addic- tion Severity Index. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 9,

- 38. 199–213. Mueser, K. T., Bellack, A. S., Morrison, R. L., & Wade, J. H. (1990). Gender, social competence, and symptomatology in schizophre- nia: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 99, 138–147. Nidecker, M., Bennett, M. E., Gjonbalaj-Marovic, S., RachBeisel, J., & Bellack, A. S. (2009). Relationships among motivation to change, barriers to care, and substance-related consequences in people with dual disorders. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 5(3), 375–391. Nidecker, M., DiClemente, C. C., Bennett, M. E., & Bellack, A. S. (2008). Application of the transtherorectical model of change: Psychometric properties of leading measures in patients with co-occurring drug abuse and severe mental illness. Addictive Be- haviors, 33, 1021–1030. O’Conner, E. A., Carbonari, J. P., & DiClemente, C. C. (1996). Gen- der and smoking cessation: a factor structure comparison of pro- cesses of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychol- ogy, 64, 130–138. Opler, L. A., Kay, S. R., Lindenmayer, J. P., & Fiszbein, A. (1992). Structured clinical interview for the Positive and Negative Syn- drome Scale. New York: Multi-Health Systems. Pelissier, B., & Jones, N. (2005). A review of gender differ- ences among substance abusers. Crime & Delinquency, 51(3),

- 39. 343–372. Prochaska, J. O., & DiClemente, C. C. (1983). Stages and pro- cesses of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51, 390–395. Prochaska, J. O., Velicer, W. F., DiClemente, C. C., & Fava, J. L. (1988). Measuring the processes of change: Applications to the cessation of smoking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psy- chology, 56, 520–528. Rachbeisel, J., Scott, J., & Dixon, L. (1999) Co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorders: A review of recent research. Psychiatric Services, 50, 1427–1433. 818 A. DRAPALSKI ET AL. Reiger, D. A., Farmer, M. E., Rae, D. S., Locke, B. Z., Keith, S. J., Judd, L. L., et al. (1990). Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse results for the epidemiologic catchment area (ECA) study. Journal of the American Medical Association, 264, 2511–2518. Test, M. A., Burke, S. S., & Wallisch, L. S. (1990). Gender differ- ence of young adults with schizophrenic disorder in community care. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 16, 331–344. Watkins, K. E., Shaner, A., & Sullivan, G. (1999). The role of gen- der in engaging the dually diagnosed in treatment. Community

- 40. Mental Health Journal, 35(2), 115–126. Weisner, C., & Schmidt, L. (1992). Gender disparities in treatment for alcohol problems. Journal of the American Medical Associ- ation, 268, 1872–1876. Winoker, G., Turvey, C., Akiskal, H., Coryell, W., Solomoon, D., Leon, A., et al. (1998). Alcoholism and drug abuse in three groups—Bipolar I, unipolars and acquaintances. Journal of Af- fective Disorders, 50, 81–89. Zilberman, M. L., Tavares, H., Blume, S. D., & el-Guedbaly, N. (2003). Substance use disorders: Sex differences and psychi- atric comorbidities. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 48(1), 5– 13. Copyright of Substance Use & Misuse is the property of Taylor & Francis Ltd and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use. Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journal Code=wswp20

- 41. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions ISSN: 1533-256X (Print) 1533-2578 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/wswp20 Theories of Motivation in Addiction Treatment: Testing the Relationship of the Transtheoretical Model of Change and Self-Determination Theory Kerry Kennedy PhD & Thomas K. Gregoire PhD To cite this article: Kerry Kennedy PhD & Thomas K. Gregoire PhD (2009) Theories of Motivation in Addiction Treatment: Testing the Relationship of the Transtheoretical Model of Change and Self-Determination Theory, Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 9:2, 163-183, DOI: 10.1080/15332560902852052 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/15332560902852052 Published online: 13 May 2009. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 3537 Citing articles: 7 View citing articles https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journal Code=wswp20 https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/wswp20 https://www.tandfonline.com/action/showCitFormats?doi=10.10 80/15332560902852052 https://doi.org/10.1080/15332560902852052

- 42. https://www.tandfonline.com/action/authorSubmission?journalC ode=wswp20&show=instructions https://www.tandfonline.com/action/authorSubmission?journalC ode=wswp20&show=instructions https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/citedby/10.1080/15332560902 852052#tabModule https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/citedby/10.1080/15332560902 852052#tabModule 163 Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 9:163–183, 2009 Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 1533-256X print/1533-2578 online DOI: 10.1080/15332560902852052 WSWP1533-256X1533-2578Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, Vol. 9, No. 2, March 2009: pp. 1–38Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions Theories of Motivation in Addiction Treatment: Testing the Relationship of the Transtheoretical Model of Change and Self-Determination Theory Theories of Motivation in Addiction TreatmentK. Kennedy and T. K. Gregoire KERRY KENNEDY, PHD Assistant Professor, Department of Social Work and Gerontology, Weber State University, Ogden, Utah, USA

- 43. THOMAS K. GREGOIRE, PHD Associate Professor, College of Social Work, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, USA This study explored the relationship between 2 theories of motivation: self-determination theory (SDT) and the transtheoretical model of change (TTM), and sought to determine whether the source of moti- vation described by SDT would predict TTM’s stage of change. SDT was operationalized as the level of internal or external motivation for treatment, and TTM was operationalized as 3 stages of change: precontemplation, contemplation, and action. Our data came from the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study published in 2004. A multinomial logistic regression analysis indicated that there was a significant relationship between source of motivation and stage of change at intake. Controlling for severity, treatment history, legal status, and primary substance use, persons entering treatment with higher levels of internal motivation were more likely to be in the action stage than the precontemplation stage. Higher levels of internal motivation also predicted a greater likelihood of being in the contemplation rather than the precontemplation stage. KEYWORDS addiction, motivation, stages of change

- 44. Received July 18, 2006; accepted February 22, 2007. Address correspondence to Kerry Kennedy, Department of Social Work and Gerontology, Weber State University, 1211 University Circle #148, Ogden, UT 84041, USA. E-mail: [email protected] weber.edu 164 K. Kennedy and T. K. Gregoire Recent years have seen an evolution in thought about the role of motivation in substance abuse treatment. Motivation was once viewed as a function of individual differences and largely related to personality traits. Individuals who did not comply with treatment were considered to be unmotivated (Clancy, 1961). Motivation is now considered more a function of an interac- tion of individual and environmental factors (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). Current views of motivation in treatment place the onus for client motivation on the clinician, recognizing that the interaction of the clinician and client “has a crucial impact on how they respond and whether treatment is successful” (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 1999, p. 3). Clients once viewed as not ready to change their behavior are now more likely seen as in need of different interventions than those perceived as more motivated

- 45. (Prochaska, DiClemente, & Norcross, 1992). Interventions such as motivational inter- viewing are based on the demonstrated assumption that the clinician need not wait for a client’s readiness but instead can impact a client’s level of motivation and guide them toward prosocial behavior (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). The change in the perception of the role of motivation has been heavily influenced by the emergence of the transtheoretical model (TTM; DiClemente, 2003; Prochaska, 1979; Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983; Prochaska et al., 1992). As described later, this theoretical perspective on a client’s readiness to change has led practitioners to recognize that motivation to change might be a malleable, dynamic, and nonlinear process. Although less well known than TTM, self-determination theory (SDT; Deci & Ryan, 1985) describes the role of internal and external factors in understanding motivation. The two theories provide distinct approaches to understanding the role of motivation in affecting change among persons who misuse substances. This article explores the relationship of these two theories and considers if the two approaches in tandem provide a greater understanding of motivation among persons with substance use disorders.

- 46. THE TRANSTHEORETICAL MODEL The TTM was derived from a compilation of 18 different psychological and behavioral theories and provides a temporal framework for describing intentional behavior change (Prochaska, 1979). Developed originally as a model for understanding client-initiated attempts to modify their nicotine addiction (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983), TTM has been adapted to a wide range of behaviors including substance use (DiClemente & Hughes, 1990). DiClemente (2003) described TTM as consisting of four interrelated dimensions of change that include stages, processes, markers, and a context of change. The stages of change are delineated with a time frame and tasks Theories of Motivation in Addiction Treatment 165 associated with movement through that stage. There are five stages of change (Prochaska et al., 1992). Persons identified in the precontemplation stage have no current intention to modify their behavior, and might not acknowl- edge that they have a problem. Persons characterized as contemplators are

- 47. thinking about addressing their problem, but have yet to take action. The preparation stage reflects a client’s intention to make some change attempt during the next month. Persons who have made an unsuccessful change effort in the preceding year are also in this stage of change. The action stage is associated with the initiation of modified substance use behavior. Typically, the action stage extends from 3 to 6 months (DiClemente, 2003). During the final maintenance stage, beginning at 6 months after behavior change, persons take steps to avoid relapse and consolidate their new lifestyle. These stages are accompanied by processes of change. Each process consists of interventions appropriate to assist a person in moving to the next stage of change (Prochaska et al., 1992). The context of change attempts to address other areas that might contribute to maintenance of the problem including interpersonal, social, and environmental dimensions (DiClemente, 2003). TTM emphasizes the importance of attempting and then maintaining new behavior in understanding motivation for change. The concept of deci- sional balance refers to the weight of the evidence for and against a certain behavior. In TTM, persons initiate change as the balance tips against the

- 48. benefits of the addictive behavior. TTM does not appear to distinguish between the importance of internal and external sources of motivation with respect to decisional balance, although early interventions do tend to empha- size external pressure. The literature on the influence of motivation type on stage of change is limited and divided. O’Hare (1996) found that people referred through the court were more likely to be in the precontemplation stage than peo- ple who were not court referred. However, Gregoire and Burke (2004) reported that persons who were legally coerced to outpatient substance abuse treatment were more likely to be in the action stage of change than precontemplation. A considerable literature has emerged on TTM, with mixed findings on its efficacy as a tool for understanding addiction and recovery. Knowledge of a client’s stage of change has been demonstrated in some studies as an important tool for predicting treatment outcomes. In particular, studies have associated a client’s stage of change with subsequent alcohol use (Heather, Rollnick, & Bell, 1993), heroin or cocaine use (Henderson, Galen, & Saules, 2004; Prochaska et al., 1994), and treatment dropout (Callaghan et al., 2005;

- 49. Edens & Willoughby, 2000; Haller, Miles, & Cropsey, 2004; Simpson & Joe, 1993). In general, clients identified as precontemplators fared worse on sub- sequent outcomes than those who presented for treatment in more advanced stages of change. 166 K. Kennedy and T. K. Gregoire However, other authors reported finding no relationship between stage of change and either posttreatment substance use (Belding, Iguchi, & Lamb, 1997; Burke & Gregoire, 2007) or Addiction Severity Index composite scores (Burke & Gregoire). Another study found the stages of change model unable to predict either treatment attendance or the percentage of days abstinent (Blanchard, Morgenstern, Morgan, Labouvie, & Bux, 2003). Critics of the TTM argue that this model is arbitrary in its division of the stages of change and the time frame of each stage (Sutton, 2001). Bandura (1997) described the TTM as “arbitrary pseudo-stages” (p. 8) and not a true stage theory. Davidson (1998) and Bandura (1997) suggested that the TTM does not include stages that are distinctly, qualitatively different from each other, noting that one stage can be considered an extension of

- 50. the previous stage. Weinstein, Rothman, and Sutton (1998) also described the specific time points of the stages as arbitrary. DiClemente (2003) acknowledged that the TTM stage model does not produce fixed stages with either a determinant order or a single linear path- way. Instead the stages are best understood as a developmental model of recovery in which the resolution of earlier tasks impacts the later stages. SELF-DETERMINATION THEORY SDT (Deci & Ryan, 1985) has been applied to many areas, such as medica- tion adherence, weight loss, and test-taking behavior in school- aged children. However, the application of this theory specifically to substance abuse has been limited (Ryan, Plant, & O’Malley, 1995; Zeldman, Ryan, & Fiscella, 2004). Nevertheless, the application of SDT might complement TTM as a framework for understanding motivation in substance misuse treatment. Whereas TTM does not place a major emphasis on the internal or external aspects of a client’s motivation to change, SDT addresses the source of motivation specifically by outlining a framework for understanding internal and external sources of motivation and the impact of each on treatment out-

- 51. comes. SDT defines motivation as consisting of six categories that describe a continuum of external to internal motivation. SDT postulates that persons with higher internal motivation should have better treatment outcomes, and that high external motivation in the absence of internal motivation is associated with less positive outcomes. Zeldman et al. (2004) found that clients in a methadone maintenance pro- gram with higher levels of internal motivation had lower relapse rates and higher program participation than externally motivated persons. Ryan et al. (1995) also found that higher internalized motivation was negatively correlated with dropping out of treatment. Their study also observed an interaction between internal and external motivation, as per- sons with both high internal and high external motivation were most likely Theories of Motivation in Addiction Treatment 167 to persist in treatment. External motivation was positively related to out- comes only when internal motivation was present. RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SDT AND TTM Both theories make important contributions to understanding

- 52. motivation among persons with substance use disorders. SDT identifies the forces that might influence an individual to initiate behavior change and the psycho- logical mechanisms that drive an individual to accomplish change. TTM identifies the change processes in individuals within a temporal dimension of motivation and provides a framework for understanding movement toward behavior change. Together, SDT and the TTM offer a more comprehensive view of moti- vation than either do independently. Whereas SDT emphasizes the influ- ence of perceived antecedents of behavior change on the individual, TTM provides structure to understand how clients move through a progression of behavior change. Although both theories incorporate information about the source of motivation, SDT more explicitly distinguishes the influence of internal and external sources of motivation. TTM refers to two markers of change—decisional balance and self-efficacy—and suggests that early influ- ences to change tend to be external as the decisional balance scale is tipped. TTM suggests that internal forces are at work as self-efficacy is acquired and change is maintained. However, efficacy refers less explicitly to motivation and more to the development of a confidence that one might

- 53. succeed in a change effort. Despite the utility of each in informing a greater understanding of motivation, a specific relationship between these two theories has yet to be determined within a population of persons who misuse substances. The purpose of this research is to explore the relationship of TTM and SDT among a sample of substance use treatment participants. In particu- lar, we seek to model the relationship between source of motivation as described by SDT and TTM’s stage of change to test the following hypotheses: (a) Higher levels of external motivation will predict mem- bership in the precontemplation stage of change; and (b) greater internal motivation will predict later stages of change, specifically contemplation and action. METHOD Data for this study were obtained from the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study–Adult (DATOS) published in 2004 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2004). The DATOS study

- 54. 168 K. Kennedy and T. K. Gregoire was conducted by Research Triangle Institute and funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. DATOS data were derived from a longitudinal pro- spective cohort design of 10,010 persons aged 18 or older. Clients from 96 programs in 11 cities were purposively chosen and interviewed at intake and again at several points during treatment. The selection of communities and programs reflected typical drug treatment programs in medium and large-sized U.S. cities and consisted of both publicly and privately funded entities. Data were collected from 1991 to 1993 via face-to-face interviews con- ducted with participants in four different treatment modalities: outpatient methadone maintenance, long-term residential, outpatient drug free, and short-term inpatient. Data for our study consisted of two waves of interviews. The first wave was from an initial interview conducted as soon as possible after admission to treatment and the second wave came from an interview that was conducted about 1 week later. Participants Of the 10,010 participants in the total sample, 8,725 had a completed first

- 55. and second intake interview on record. Although the initial two waves of DATOS data consisted of a purposive sample of treatment admissions, data for the DATOS follow-up interviews were derived from a random sample. The sample employed for our analysis consisted of a random sample drawn from those individuals with completed Wave 1 and 2 data. Table 1 describes the characteristics of the sample in greater detail. The majority of the 4,347 participants were male (67.1%), and most were over the age of 30 (58.2 %), with a mean age of 32.5 (SD = 7.4). African Americans made up 46.7% of our sample, 38.7% were White, and 11.9% were Hispanic. Most respondents (55.0%), had no current legal involvement, although 31.9% reported being on probation or parole. Most of the respondents reported being unmarried at the time of their first interview; 45.4% were never married, 19.5% were currently married, 12.1% were living as married, and 13.5% reported being divorced. In terms of education, about one third (38.4%) of the respondents had a high school degree, and another third (35.8%) had less than a high school degree. Most respondents were not working at the time of their initial interview. Slightly less than half of the respondents (42.4%) identified the major source of

- 56. income as legal work, and about one fifth (20.4%) stated that public assis- tance was their major source of income. Table 2 describes participant substance use. The majority (51.1%) iden- tified crack or cocaine as their primary drug problem, followed by heroin and other opiates (20.6%), alcohol (12.2%), marijuana (3.0%), and amphet- amines (2.4%). Theories of Motivation in Addiction Treatment 169 The average number of prior treatments for substance use disorders was 1.95 (SD = 4.4). Slightly less than half of the participants (44.7%) indi- cated that this was their first treatment experience for substance misuse. About one in five persons indicated that this was their second treatment experi- ence (20.5%) with the remaining participants reporting between three and six prior treatment episodes. About one third (34.7%) of the participants identified their primary referral source as self, followed by family or friends (30.9%), and the legal system (21.9%). TABLE 1 Sample Characteristics Variable N %

- 57. Gender Male 2,915 67.1 Female 1,432 32.9 Ethnicity African American 2,029 46.7 White 1,684 38.7 Hispanic 517 11.9 Other 117 2.7 Marital status at intake Never married 1,974 45.4 Married or living as married 1,374 31.6 Previously married 992 22.8 Missing 7 0.2 Age at admission 18–20 124 2.9 21–25 656 15.1 26–30 1,033 23.8 31–35 1,147 26.4 36–44 1,117 25.7 44 + 270 6.2 Educational level No high school degree 1,555 35.8 High school degree 1,670 38.4 Some college 741 17.0 College degree 377 8.7 Missing 4 0.1 Major source of income Legal work 1,843 42.4 Public assistance 887 20.4 Illegal sources 642 14.8 Family or friends 291 6.7

- 58. Social Security 198 4.6 No income 198 4.6 Other 61 1.4 Missing 227 5.2 Criminal justice status No current legal status 2,389 55.0 Current legal status 1948 44.8 Missing 10 0.2 170 K. Kennedy and T. K. Gregoire We assessed problem severity by considering frequency of substance use and reports of regular use of more than one substance. Almost half of the respondents (48.4%) indicated that they used their primary drug daily, almost every day, or on multiple occasions in a single day. An additional 35.5% reported using one to six times per week, 3.3% reported using less than once a week, and 4.6% reported no use at the time of their initial inter- view. The number of different drugs used weekly ranged from zero to eight. Measures and Procedure To control for the role of problem severity we created a severity measure and categorized respondents into one of three severity groups. Participants were assigned to a low-severity group when the frequency of