Representation of Interests MatrixPOL443 Version 31Univer.docx

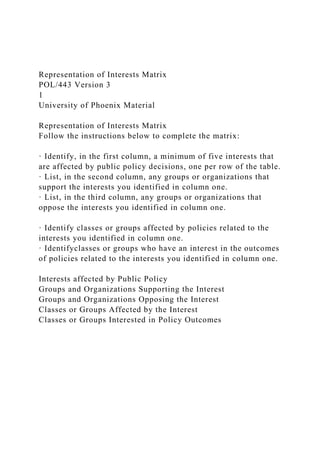

- 1. Representation of Interests Matrix POL/443 Version 3 1 University of Phoenix Material Representation of Interests Matrix Follow the instructions below to complete the matrix: · Identify, in the first column, a minimum of five interests that are affected by public policy decisions, one per row of the table. · List, in the second column, any groups or organizations that support the interests you identified in column one. · List, in the third column, any groups or organizations that oppose the interests you identified in column one. · Identify classes or groups affected by policies related to the interests you identified in column one. · Identifyclasses or groups who have an interest in the outcomes of policies related to the interests you identified in column one. Interests affected by Public Policy Groups and Organizations Supporting the Interest Groups and Organizations Opposing the Interest Classes or Groups Affected by the Interest Classes or Groups Interested in Policy Outcomes

- 3. Recalling anti-racism Ghassan Hage School of Social and Political Sciences, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia ABSTRACT Despite its many achievements and some remarkable victories against the forces of racism in their variety of forms, it cannot be said that anti- racism has been particularly successful as a social, cultural, and political force. This essay uses Bruno Latour’s figure of the ‘recall’ to rethink certain elements of the anti- racist tradition. Latour sees the figure as combining both ‘recalling’ in the sense of remembering, but also ‘recalling’ in the way a company recalls a product when it realises it has some defect. In much the same way, the essay uses the idea of ‘recalling anti-racism’, firstly, in order to stay in touch with anti-racism’s ‘founding principles’, to develop a sense of the cumulative gain that has been made throughout its history, and, secondly, in order to critically re-examine how it can be modified and made more efficient.

- 4. ARTICLE HISTORY Received 5 January 2015; Accepted 27 April 2015 KEYWORDS Anti-racism; neo-liberalism; reciprocity; mutuality; critical anthropology; racism Introduction There is little doubt that the ‘re-configuring’ of anti-racism is an urgent task today. As a current of thought and as a social movement, anti- racism has a long history. From the opposition to slavery, to the anti-colonial struggles, to the civil rights movement in the USA, to the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa, to today – where anti-racism is most notably present in the struggles in support of asylum seekers and against the Israeli treatment of Palestinians in Israel/Palestine – anti-racism has been and remains a vital and important current of thought and social movement. It embodies the noblest of all human values – at the very least, a belief in the right of all human beings to be treated with dignity and respect regardless of where they come from and how they happen to be classified. Yet, despite this long history and some remarkable victories against the forces of racism in their variety of forms, it cannot be said that anti-racism has been particularly successful as a social, cultural, and

- 5. political force. Every- where we look today, racism is on the rise. In Australia, and also in the USA and © 2015 Taylor & Francis CONTACT Ghassan Hage [email protected] ETHNIC AND RACIAL STUDIES, 2016 VOL. 39, NO. 1, 123–133 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2016.1096412 mailto:[email protected] Canada, if we look at the treatment of Indigenous people and the immigrant populations originating from the Third World, or at the rate of imprisonment of black populations, all remain marked by excessive racism. Likewise is the treatment of asylum seekers everywhere around the world. Most importantly, we are seeing a massive rise in virulently racist and intolerant forms of ethno- religious nationalism, with Zionist nationalism in Israel being an extreme case of what is fast becoming the rule rather than the exception. But perhaps, nowhere is the salience of racism made clearer than in the case of South Africa, the country where the forces of anti-racism have registered what is undoubtedly their greatest victory. For there, and despite the undeniable victory, racism remains an enduring social force, leaving its imprint on

- 6. many facets of South African life. It is with all of the above in mind that I want to investigate the need to reconfigure anti-racism through the process of ‘recalling’ it. ‘Recalling’ has been put forward by Latour (2007) as a critical way of reflect- ing on modernity. It combines both recalling in the sense of remembering to ensure we build on past achievements, but also recalling in the way a company recalls a product when it realises it has some defect. As Latour (2007) highlights: In no way does this recall aim to damage the product, nor, of course, to lose market share. Rather, it has quite the opposite strategy. By showing consumers the care it takes with the quality control of its goods and the safety of their users, it wants to demonstrate initiative, rebuild media confidence, and, if possible, recommence the production that was too quickly halted. (11) It is in this spirit, then, that I want to initiate a recalling of anti- racism. The functions of anti-racism More so than ‘modernity’, anti-racism is a ‘product’ with a well defined func- tion, and it is important, indeed, to recall, in the usual sense of the word, what these functions are. First, in order to stay in touch with its

- 7. ‘founding principles’ and also in order to develop a sense of the cumulative gain that – despite the shortcomings – has nonetheless been made in the history of anti-racism, I want to highlight six central functions. Although these clearly overlap in prac- tice, I will list them for the purpose of exposition. (1) Reducing the incidence of racist practices: Anti-racists have struggled throughout history to create social and legal pressures that make it diffi- cult for racists to externalize their racism whether in society at large (everyday racism) or within institutions (structural racism). (2) Fostering a non-racist culture: This differs from the cultural work needed to stop racists externalizing their racism as it involves the more difficult work of using municipal, educational, and artistic forums and institutions, aiming to ensure that people are not racist in the first place. 124 G. HAGE (3) Supporting the victims of racism: This includes the various modes of pro- tecting and offering shelter and counselling to victims of racist violence and racist abuse. (4) Empowering racialized subjects: The struggles to bring

- 8. about anti-racist laws and to create networks of solidarity do not only have the effect of stopping racists and helping victims; they can also be directed at making the racialized more autonomous and more able to withstand and fight back against racism. Such work has a more lasting effect in the long run and, as such, is more important than helping victims. (5) Transforming racist relations into better relations: Like feminism, anti-racism is an ambivalent struggle. It involves by necessity a war-like sentiment of enmity towards the racists as a dominant, oppressive, and sometimes violent group, but, at the same time, such enmity cannot be left unchecked such as to include an ethos of extermination. Instead, anti- racists need to offer those who are racializing them, in the same way fem- inist women offer sexist men, modes of coexisting and relating that con- stitute an alternative to the dominant racist or sexist relation. (6) Fostering an a-racist culture: Finally, and perhaps ultimately, anti-racists aim to create a society in which race has no significance as a criterion of identification. As a long critical intellectual anti-racist tradition has taught us, we do not need – and it could still be described as racist – to settle for a society that naturalizes racial identification. We

- 9. can and should aim where appropriate for a state of affairs in which racial identi- fication is no longer a relevant or salient mode of identification. The a- racial is thus an ideal of a social space characterised by a radical indiffer- ence to race. It is when looking at these functions and objectives that the necessity of ‘recal- ling’ anti-racism in its full Latourian sense becomes clear. While anti-racism has had some notable successes at achieving its goals, it has been, as already mentioned, far from an efficient, fault-free product. It has often failed to perform and rise to the situations it is confronting. Indeed, if we are to compare racism and anti-racism as products, we can say that across history racism has been far more successfully ‘recalled’ and made operationally suit- able for a variety of socioeconomic and cultural environments. It has morphed and shown a capacity to target a variety of people, sometimes many at the same time: blacks, Asians, Arabs, Jews, Roma, and Muslims. It has been used as a tool of segregation, a tool of conditional integration, and, most dramati- cally, a tool of extermination. It has efficiently constructed its object, success- fully adapting to the dominant modes of classification of the time, be they phenotypical, biological, cultural, or a combination of these and

- 10. more. Comparatively speaking, anti-racism has been conceptually rather ossified and is always trying to catch up with the racists’ fluid modes of classification. Anti-racist academics have certainly contributed to this ossification, perhaps ETHNIC AND RACIAL STUDIES 125 more so than activists. While racists have happily moved from one form of racism to another, caring little about logical contradictions, inconsistencies, and discrepancies in their argumentations, too many anti-racist academics spend an inordinate amount of time trying to judge racists on precisely such grounds. In a classical case of what Pierre Bourdieu (1990) calls ‘project- ing into the object one’s relation to the object’ (27), they criticise racists as if the racists are fellow academics with whom they are having disagreements in a tutorial room about how to interpret reality. The performativity of racist statements and more obviously racist practices, which is what is most impor- tant to the racists themselves, is given far less attention than needed. Instead, the racists’ greatest sins are made to be interpretative/intellectual ones. They are accused of being bad thinkers: they are ‘essentialists’, they

- 11. deviate from ‘classical’ biological racism, or they are making false statements about reality that the anti-racist academics can empirically correct by highlighting a lot of statistical data that proves them incorrect: ‘No, there aren’t that many asylum seekers trying to get into the country’ or ‘No, there are no ghet- toes here. Look at the demographic data’-type argumentation. It is because of such tendencies that recalling anti-racism is a crucial task. It is particularly so since racism for the last couple of decades or so has yet again been undergoing an important reconfiguration, becoming intimately fused with the logic and needs of neo-liberal capitalist accumulation. To recall anti-racism now, in the midst of this transformation, might allow us to develop an anti-racism that is evolving in continual response to, rather than trying to catch up with, the racisms it is trying to oppose. The neo-liberal recalling of racism One of the most important transformations that have shaped the new ‘neo- liberal racism’ is the increasingly important role that nationalist ideologies play in securing the relative cohesion of most nation states. Economic globa- lization has meant that very few nations are left with a national economic structure that works as a solid base for securing the

- 12. togetherness of the nation regardless of what people within the nation thought. This has meant, among other things, a relative increase in the importance of the func- tion of the ideological (e.g. national values, national histories) as a centripetal force securing both the practical and the ideological unity of the nation-state. Because of this centrality, the social forces that take on the task of protecting ethno-national ideologies develop an increased racist intolerance towards the plurality of ideas and identities that not long ago marked the most benign forms of multiculturalism. Such pluralities are increasingly constructed as cen- trifugal forces of disintegration and are systematically attacked as a national threat. 126 G. HAGE The second feature of neo-liberal globalization that is having an impor- tant impact on shaping the dominant forms of racism in the West is the increasing move towards a de-industrialized landscape. The current figure of the unwanted asylum seeker as opposed to the liminal but included migrant workers of the post-World War II is metonymic of a changing economy characterized by more prevalent figures of

- 13. undesirability and dis- posability. Despite the plurality of forms that racism has taken throughout history, it has always fluctuated between two tendencies: the racism of exploitation and the racism of extermination. The first is deployed when the racialized are considered as valuable such as in the case of slavery or migrant workers. The second dominates when the racialized are considered harmful, or at least when they are evaluated as more harmful than they are useful, such as in the case of anti-semitism, as well as in certain instances of colonial encounters. In the first case, racism works to marginalize people in society, ensuring they have a place in it even if it is a precarious place. In the second, racism aims to marginalize people from society, ensuring they have no social or even physical presence in it whatsoever – this could be through active physical extermination, or through passive extermination: letting people rot through a strategy of total neglect the way one lets an old truck rust away on one’s property, or, in a similar manner, through ensuring the targeted people remain on the outer side of the borders they are aiming to cross, as with asylum seekers. The third feature is the rise of particularist anti-racism. This is the anti- racism of those who are racialized and are as such struggling

- 14. against their racialisation. But in their struggle, what is important to them is not that ‘racism is wrong’. Rather, it is that racism against them is wrong. Such people don’t mind racism as such, they mind being subjected to it themselves. Indeed, they often are happy to dispense racism themselves. Nowhere is this racist particularist anti-racism, with its capacity to racialize others in the name of fighting against one’s racialisation, more powerfully present and institutio- nalized than in the state of Israel today. But it can even be said that this par- ticularism has become a generalized cultural form with so much racism today being dispensed by racists claiming to be racialized themselves. Even white populations in Europe, the USA, Canada, and Australia, with their long history of colonization, have happily taken it on board, often arguing that they are subject to ‘reverse racism’. This particularist anti-racism raises what is perhaps the most crucial point that needs to be considered in the process of recalling racism: to what extent is anti-racism wedded to an ‘alter-political’ conception of society? That is, to what extent does it not only work on opposing existing racism, but also work on thinking through and working for a non-racist society.

- 15. ETHNIC AND RACIAL STUDIES 127 Anti-racism and anthropology’s three modes human of existence Perhaps one of the richest and most critical dimensions of anthropology, which makes it so particularly suitable for thinking alter- political questions, is its long tradition of dealing with cultures that the colonial expansion of our capitalist modernity has put us in touch with, but which nonetheless remain outside it in a variety of ways. Anthropology investigates modes of thinking and existing that strike us to begin with as radically different from our own. Yet, at the same time, it invites us to note how this radical difference actually speaks to us; that is, we come to realise that there are nonetheless certain commonalities between our own lives and those seemingly exotic modes of existence that have been depicted and analysed. This is precisely when anthropology becomes critical: it invites us to see that there are whole realities or dimensions of realities that were hidden from us, even though they have always been constitutive elements of our lifeworld. As such, critical anthropology helps us become conscious of the fact that our

- 16. reality is far more layered and differentiated than we thought and that, just as there are dominant and dominated forces within a reality, there are also dominant and dominated realities. The anthropological tradition has highlighted two human modes of exist- ence that I want to introduce here, not only because of their intrinsic impor- tance but also because they speak in particular to the question of racism and anti-racism before us. These are what I will refer to as the reciprocal and the mutualist modes of existence. They can be differentiated from the mode of existence that dominates our own modernity, what I will call the domesticat- ing mode of existence. To speak of human modes of existence is to speak of a human mode of inhabiting, being enmeshed in and relating to the world that is part and parcel of constituting the world. I will define each of these modes of existence through their way of conceiving, creating, and relating to other- ness since this is what concerns us most here. The domesticating mode of existence, with which we are most familiar, is a world dominated – although, one must stress, far from saturated – by an instrumentalization of one’s surroundings. It creates an otherness that is mostly conceived as an object that needs to be dominated for utilitarian pur-

- 17. poses. A logic of extraction of value, physical and symbolic, prevails through- out this world. All differences that are articulated to domestication become a form of polarization: human–animal, man–woman, white–black. The bound- ary between self and other is characterized by the problem of how to domi- nate and maintain sovereignty over the other. The reciprocal mode of existence offers a different relationality, grounded in the logic of the gift. The radical difference that is inherent in gift exchange was initially and classically highlighted in the work of Marcel Mauss ([1925] 2000) 128 G. HAGE on the subject. What is difficult about the order of the gift is that, in the first instance, it is hard to see how the logic of the gift is any different from the instrumental reason that rules in the realm of domestication. For indeed, at one level, it does not take particularly sharp analytical skills to uncover a calcu- lative logic of self-interest that is a feature of gift exchange. The brilliance of Mauss’s work was to insist that if one sees in the gift only this logic of self-inter- est, one misses a different dimension, which is precisely the space of radical difference where it takes us. In that space, things are not merely

- 18. ‘offered’ as gifts in a strategically motivated act. Rather, the reciprocal gift relation is a relation that is always a surplus to the instrumental calculative relation. People, animals, plants, and objects stand as gifts towards each other. Their mere presence before each other is constituted by a kind of inter-giftness. The exclamations of joy that accompany a child entering a room is a good example of the way someone’s presence by itself is experienced as an offering. Some forms of religious thought capture this dimension by making life and everything that exists a gift of God requiring to be recognized as such, and where the very recognition of this giftness, the sentiment of gratitude, is itself a form of reciprocating the gift. Mauss’s analysis of gift exchange showed that while this reciprocal gift-based mode of existence is minor in our society, and indeed tends to become negligible with the increased domi- nance of calculative instrumental logic, there are societies where this dimension remains far more pronounced. If the order of domestication invites an experi- ence of the boundary as an intrinsic component of defining and consolidating one’s sovereignty, in the order of reciprocity the border between self and other is primarily perceived as the site of exchange and inter- relationality.

- 19. The mutualist mode of existence is also about inter- relationality. But it is in an inter-relationality of a different order. I am borrowing the concept of mutuality here from recent work by Sahlins (2012) on kinship. It highlights an order of existence where people (and animals, plants, objects, and so on) exist in each other. ‘He is from us and in us,’ the Lebanese say to empha- size that someone is strongly connected to them. Mutualism is this sense that others are ‘in us’ rather than just outside us. It can be argued that anthropol- ogy’s research on mutualist forms of existence begins with the earliest works of Tylor (1976) on animism. But its critical anthropological ramifications became more developed with Lucien Lévy-Bruhl’s work on ‘participation’: a mode of living and thinking where we sense ourselves and others as partici- pating in each other’s existence, where the life force of the humans and the non-humans that surround us are felt to be contributing to our own life force (Keck 2005). If the domesticating mode of existence stresses a sense of boundaries concerned with the delineation of a space of sovereignty, and the reciprocal mode of existence highlights boundaries and borders as a zone of exchange, the mutualist mode of existence underscores a reality where boundaries between self and other, human and animal, and so on,

- 20. ETHNIC AND RACIAL STUDIES 129 are far less absolute and even non-existent, where we experience an interpe- netration between self and other. In order to grasp what this means for our understanding of racism and anti- racism, it is important to stress again the critical anthropological reach of these modes of existence. Despite some facile claims to the contrary by people eager to attack anthropology’s supposed colonial exoticization of otherness, neither Marcel Mauss nor Lévy-Bruhl, nor any of the anthropologists who took their work seriously, claimed something as simplistic as ‘Look at us. We are modern and rational, and look at those others who are so different from us that they live in a world of gift exchange, or in a world of mutuality.’ Both emphasized that rational instrumental calculative forms of thinking and living existed in the societies they were examining. They respectively argued, however, that the logic of the gift and the logic of participation were more pronounced in those societies than they were in our own. Thus, they were also claiming right from the start that the logic of participation and the logic of gift exchange were not as foreign to us as we

- 21. might first think. Our world must be made out of a multiplicity of modes of existence, and if those modes of existence like gift exchange and mutuality speak to us, it is because they are always already one of our many modes of creating/ relating to the world. We can say that Mauss and Lévy-Bruhl were multi-realists well before Viveiros de Castro (2014) introduced the concept. It is in this sense that their anthropology was a critical anthropology: it works like a sociocultural archaeology, digging up and making apparent modes of existence that, while less salient in our lives, are nonetheless very much part of them. The domesti- cating, reciprocal, and mutualist modes of existence are concurrently part of everyone’s lives even if one dominates over others in certain social, historical, or personal circumstances. Thus, I might see in a tree something I need to instrumentalize, to cut in order to ‘extract’ its wood and build myself a house, and in that sense the tree exists for me in the domesticating order of reality. What Mauss and others would insist upon, however, is that there is another mode of relating to the tree, which occurs concurrently, where its mere presence, regardless of the value of its wood, is a gift: I look at it and I say, ‘Thank you for existing, even though I am sorry that I need to cut you down.’ Likewise, I might consciously or unconsciously feel that

- 22. the being of the tree and its life force is participating in my own existence and enhancing my own life force, and when I cut the tree I might, also consciously or uncon- sciously, feel that my own life force has been diminished when I cut it down. I am living and relating to things in all these three forms of existence at the same time, and perhaps many others of which I am not conscious. With this in mind, I want now to move to show the relevance of this for a recalling of anti-racism. The crucial point that needs to be emphasized here is that racists, like all of us, are multi-realists in practice, while it is only we, the anti-racists, who have clung to a mono-realist ‘rationalist’ mode of existence 130 G. HAGE in theory for too long. When, for example, racists classify someone as extermin- able, they don’t only do so from an instrumentalist/calculative rationality point of view. To be sure, they do classify them in this way, perceiving them as super- fluous and harmful. But this is not enough to explain the lethal and visceral nature of exterminability. Racists also experience and classify the racialized within the realm of reciprocity. As I have argued above, the way we greet a

- 23. child entering a room is a good example of treating someone’s presence as a gift in itself. What is crucial to add here is that it is precisely through this process that we instil in children a healthy narcissistic sense of self-worth. It goes without saying that we might under- or over-do it sometimes, but it remains true nonetheless that it is good for us to walk around knowing sublim- inally that our worthiness is not merely relative to how ‘useful’ others think we are. It is precisely this intrinsic sense of worthiness inherent to our very pres- ence, and that is beyond or outside instrumental reason, that the racists try to withhold from those they are racializing and in so doing try to remove them from the reciprocal mode of existence. It is this removal that adds an important layer to what it means to be exterminable. Indeed, in the case of asylum seekers, the withholding of this intrinsic giftness, and the symbolic/ psychological injury this entails, is one of the most important dimensions of the racist encounter. While this already adds depth and complexity to our understanding of the racism of extermination, it is by understanding the way racism also draws on the experience of mutuality that the true murderous intent of this racism can

- 24. be more fully understood. As has been made clear above, the mutualist order of existence involves a sense of inter-penetration of existence whereby the other is seen as participating in our very existence and vice versa. In exempli- fying this, I used the positive example of the life force of others enhancing our own life force. Yet one of the vilest expressions of racism emanates from a negative experience of this mutuality, an experience akin to forms of black magic and sorcery: seeing in the existence of the other malefic forces that are diminishing rather than enhancing one’s own life force. This is indeed one of the most unpleasant and visceral forms that racism takes. Here, the racist conceives of the other in the figure of the ‘dementor’ in Rowling’s Harry Potter novels: the mere proximity of someone they classify as black, Asian, Arab, or Jew is seen as sucking one’s life and soul away from them, leaving them drained. Not only is the presence of the other not a gift, it is also an actual ‘existential threat’ that animates our exterminatory impulses. Writing anti-racism What I have tried to show in the above is that by taking the many dimensions of the racism of extermination on board we can begin to think of an anti-

- 25. ETHNIC AND RACIAL STUDIES 131 racism that can rise to its multi-realist complexity. For if racism constitutes itself within the domesticating, reciprocal, and mutualist modes of existence, this certainly does not mean that these modes of existences are intrinsically racist. Modes of existence are like all social worlds, spaces of struggle. Just as racism finds resources in them to thrive, so can anti-racism and – most importantly – the alter-politics confronting racism. Just as the order of the gift implies a move away from the domesticating order of instrumental valor- ization, the reciprocal mode of existence offers us an anti- racism that moves beyond the ‘valorization of the other’ that characterizes multicultural anti- racism. Anti-racism, then, without vacating the empirical/rational ground in which it has been mostly grounded, can productively move to think of itself as affective, and even as magical, in ways that speak to the racist sentiments and affects generated in the realm of reciprocity and mutuality. More impor- tantly, the mutualist mode of existence offers us experiences where the very distinction between self and other disappears, and as such offers one of the most important grounds for setting the utopia of the a-racial on secure

- 26. grounds. It is here that we come to the question of anti-racist writing. For what is true about anti-racist practices in general is also true of the particularities of anti-racist writing as a practice. For writing, like any other practice, is also enmeshed in a multiplicity of worlds, with their corresponding forms of otherness. One can write ‘about’ the racialized, treating them as passive sub- jects of analysis. There is no doubt that such a form of anti- racist writing can be over-analytical, treating racism, racists, and the racialized as objects of what amounts to analytical domestication. This is when all writing aims to do is to ‘capture’ reality, a concept with an impeccable domesticating pedi- gree. But this is not all that anti-racist writing does or can do. One’s writing can take the form of a gift to the racialized. There is a long tradition of sociological and anthropological writing reflecting on how to write ‘with’ rather than just ‘about’ one’s informants. This is particularly true of ethno- graphies of indigenous people, where anthropologists have a long history of being sensitive to questions of reciprocity. Anti-racist writers can learn a lot from these ethnographies. Finally, a piece of anti-racist writing can be in itself a form of life that participates in enhancing the being of the

- 27. racialized, aiming to speak to them in the sense of speaking into them. Sometimes this can be a question of style: it is hardly a revelation for anti-racist activists that one can write something like ‘1-in-3 African Ameri- cans will go to prison’ as either a mere ‘depressive’ confirmation of margin- alization or as an invigorating call to arms stressing the racialized’s agency and capacity for resistance. I think that the poetic/phenomenological tra- dition, such as what one finds in the work of Michael Jackson (see for instance Jackson 2009), can offer an inspiration for a more consciously mutualist writing in this domain. 132 G. HAGE The question then becomes: what does it mean to become more conscious of anti-racist writing as enmeshed in this plurality of modes of existence? I would like to think that, at the very least, such consciousness would widen the writer’s anti-racist strategic capacities and render anti-racist thought more efficient at combatting racism. This is crucial as anti- racist political forces face the lethal neo-liberal forms of exclusion meted out on the racia- lized today. For example, the ease with which asylum seekers are radically

- 28. expelled and disallowed to set a footing in society appears at one level as a form of instrumental/rational/bureaucratic decision making, even if judged as extremely harsh. Yet such extremism is impossible without a culture of dis- posability and exterminability in which this exclusion is grounded, and that is far from being entirely instrumental/rational/bureaucratic. It goes without saying that from a disciplinary perspective it is this culture that is by definition the appropriate domain of anthropological investigation and writing. It so happens that, politically and ethically, it is also the most important to address, understand, and struggle to transform. References Bourdieu, Pierre. 1990. The Logic of Practice. Cambridge: Polity Press. Jackson, Michael. 2009. The Palm at the End of the Mind: Relatedness, Religiosity and the Real. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Keck, Frédéric. 2005. “Causalité mentale et perception de l’invisible: Le concept de par- ticipation chez Lucien Lévy-Bruhl.” Revue Philosophique de la France et de l’Etranger 130: 303–322. Latour, Bruno. 2007. “The Recall of Modernity: Anthropological Approaches.” Cultural Studies Review 13: 11–30.

- 29. Mauss, Marcel. [1925] 2000. The Gift: Forms and Functions of Exchange in Archaic Societies. Translated by W. D. Halls. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. Sahlins, Marshall. 2012. What Kinship is – And is Not. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Tylor, Edward B. 1976. Primitive Culture: Researches into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Language, Art, and Custom. New York: Gordon Press. Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo. 2014. Métaphysiques Cannibales [Cannibal Metaphysics]. Edited and translated by Peter Skafish. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ETHNIC AND RACIAL STUDIES 133 AbstractIntroductionThe functions of anti-racismThe neo-liberal recalling of racismAnti-racism and anthropology's three modes human of existenceWriting anti-racismReferences << /ASCII85EncodePages false /AllowTransparency false /AutoPositionEPSFiles false /AutoRotatePages /PageByPage /Binding /Left /CalGrayProfile () /CalRGBProfile (Adobe RGB 0501998051) /CalCMYKProfile (U.S. Web Coated 050SWOP051 v2) /sRGBProfile (sRGB IEC61966-2.1) /CannotEmbedFontPolicy /Error /CompatibilityLevel 1.3

- 30. /CompressObjects /Off /CompressPages true /ConvertImagesToIndexed true /PassThroughJPEGImages false /CreateJobTicket false /DefaultRenderingIntent /Default /DetectBlends true /DetectCurves 0.1000 /ColorConversionStrategy /sRGB /DoThumbnails true /EmbedAllFonts true /EmbedOpenType false /ParseICCProfilesInComments true /EmbedJobOptions true /DSCReportingLevel 0 /EmitDSCWarnings false /EndPage -1 /ImageMemory 524288 /LockDistillerParams true /MaxSubsetPct 100 /Optimize true /OPM 1 /ParseDSCComments false /ParseDSCCommentsForDocInfo true /PreserveCopyPage true /PreserveDICMYKValues true /PreserveEPSInfo false /PreserveFlatness true /PreserveHalftoneInfo false /PreserveOPIComments false /PreserveOverprintSettings false /StartPage 1 /SubsetFonts true /TransferFunctionInfo /Remove /UCRandBGInfo /Remove /UsePrologue false

- 31. /ColorSettingsFile () /AlwaysEmbed [ true ] /NeverEmbed [ true ] /AntiAliasColorImages false /CropColorImages true /ColorImageMinResolution 150 /ColorImageMinResolutionPolicy /OK /DownsampleColorImages true /ColorImageDownsampleType /Bicubic /ColorImageResolution 300 /ColorImageDepth -1 /ColorImageMinDownsampleDepth 1 /ColorImageDownsampleThreshold 1.50000 /EncodeColorImages true /ColorImageFilter /DCTEncode /AutoFilterColorImages false /ColorImageAutoFilterStrategy /JPEG /ColorACSImageDict << /QFactor 0.90 /HSamples [2 1 1 2] /VSamples [2 1 1 2] >> /ColorImageDict << /QFactor 0.40 /HSamples [1 1 1 1] /VSamples [1 1 1 1] >> /JPEG2000ColorACSImageDict << /TileWidth 256 /TileHeight 256 /Quality 15 >> /JPEG2000ColorImageDict << /TileWidth 256 /TileHeight 256 /Quality 15

- 32. >> /AntiAliasGrayImages false /CropGrayImages true /GrayImageMinResolution 150 /GrayImageMinResolutionPolicy /OK /DownsampleGrayImages true /GrayImageDownsampleType /Bicubic /GrayImageResolution 300 /GrayImageDepth -1 /GrayImageMinDownsampleDepth 2 /GrayImageDownsampleThreshold 1.50000 /EncodeGrayImages true /GrayImageFilter /DCTEncode /AutoFilterGrayImages false /GrayImageAutoFilterStrategy /JPEG /GrayACSImageDict << /QFactor 0.90 /HSamples [2 1 1 2] /VSamples [2 1 1 2] >> /GrayImageDict << /QFactor 0.40 /HSamples [1 1 1 1] /VSamples [1 1 1 1] >> /JPEG2000GrayACSImageDict << /TileWidth 256 /TileHeight 256 /Quality 15 >> /JPEG2000GrayImageDict << /TileWidth 256 /TileHeight 256 /Quality 15 >> /AntiAliasMonoImages false /CropMonoImages true /MonoImageMinResolution 1200

- 33. /MonoImageMinResolutionPolicy /OK /DownsampleMonoImages true /MonoImageDownsampleType /Average /MonoImageResolution 300 /MonoImageDepth -1 /MonoImageDownsampleThreshold 1.50000 /EncodeMonoImages true /MonoImageFilter /CCITTFaxEncode /MonoImageDict << /K -1 >> /AllowPSXObjects true /CheckCompliance [ /None ] /PDFX1aCheck false /PDFX3Check false /PDFXCompliantPDFOnly false /PDFXNoTrimBoxError true /PDFXTrimBoxToMediaBoxOffset [ 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 ] /PDFXSetBleedBoxToMediaBox true /PDFXBleedBoxToTrimBoxOffset [ 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 ] /PDFXOutputIntentProfile (None) /PDFXOutputConditionIdentifier () /PDFXOutputCondition () /PDFXRegistryName ()

- 34. /PDFXTrapped /False /Description << /ENU () >> >> setdistillerparams << /HWResolution [600 600] /PageSize [595.245 841.846] >> setpagedevice Patterns of minority and majority identification in a multicultural society Alita Nandi and Lucinda Platt (Received 2 October 2014; accepted 20 April 2015) There has been increasing investigation of the national and ethnic identification of minority populations in Western societies and how far they raise questions about the success or failure of multicultural societies. Much of the political and academic discussion has, however, been premised on two assumptions. First, that ethnic minority and national identi- fication are mutually exclusive, and, second, that national identification forms an overarch- ing majority identity that represents consensus values. In this paper, using a large-scale nationally representative UK survey with a varied set of identity questions, and drawing

- 35. on an extension of Berry’s acculturation framework, we empirically test these two assump- tions. We find that, among minorities, strong British national and minority identities often coincide and are not on an opposing axis. We also find that adherence to a British national identity shows cleavages within the white majority population. We further identify vari- ation in these patterns by generation and political orientation. Keywords: identity; UK; British; ethno-religious group; acculturation; second generation Introduction There has been extensive recent debate on the success or otherwise of ‘multicultural- ism’. On one side has been the claim that the multiculturalist project can incorporate diverse populations within a common framework (Kymlicka 1996; Modood 2007; Parekh 2000). On the other, there has been an explicit anxiety about the extent to which multicultural responses to diversity foster exclusive minority and religious identities and undermine common cause (Cameron 2011; Huntington 1993). The endorsement of national identity by minorities is often taken to be an indicator of their incorporation into the receiving country society, and to represent both accep- tance of shared national values and implicit rejection of ethnic or cultural distinctive- ness (Reeskens and Wright 2013). Conversely, maintenance of strong ethnic identities is read as problematic for an integrated society and a challenge

- 36. to a national consensus. There are, however, two features of this second narrative that merit further interrog- ation. First, ethnic and national identities are not mutually exclusive, since identities are not necessarily binary or oppositional (Verkuyten and Yildiz 2007). Moreover, the evi- dence is unclear on whether greater diversity reduces national belonging (Masella 2013). Second, the emphasis on the significance of national identification assumes that such an identity is endorsed by the population as a whole and represents a Ethnic and Racial Studies, 2015 Vol. 38, No. 15, 2615–2634, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2015.1077986 © 2015 Taylor & Francis consensus of values. This assumption is also open to question (Kiely, McCrone and Bechhofer 2005). This paper explores both of these assumptions using the case of the UK, capitalizing on a unique, nationally representative data source to analyse identification of both min- orities and the majority. We utilize and extend Berry’s (1997) acculturation framework, applying the concept of identity acculturation not only to the extent to which minorities

- 37. maintain single or dual identities, but also to diversity in identities among the white majority population. We exploit the fact that the UK’s majority population comprises English, Welsh, Scots and Northern Irish, and investigate variation in identification with each of these identities and/or with an overarching British national identity. We are thus able to advance understanding of ethnic and national identities across the whole population. We also aim to expand the quantitative evidence base on correlates of variations in national identity across ethnic groups and generations, particularly given debates around how education and socio-economic status vary with national identification (Kesler and Schwartzman 2015). We argue that when people have other secure sources of identification, such as those offered through higher education or occu- pational status, they may feel less invested in national identities (Nandi and Platt 2012). We also evaluate how far age, sex, immigrant generation (for minorities) and within-UK country of birth (for the majority) influence the extent to which national and ethnic identities are experienced as salient (Bechhofer and McCrone 2012; Georgiadis and Manning 2013; Jaspal and Cinnirella 2013; Maxwell 2006; Platt 2014). We additionally test for the contributory role of experience of harassment among minorities, since feelings of acceptance have been shown to correlate with feel-

- 38. ings of belonging (Crul and Schneider 2010; Fischer-Neuman 2014; Georgiadis and Manning 2013; Maxwell 2006); and we address the role of political engagement in contributing to identity expression (Heath et al. 2013; Verkuyten and Reijerse 2008). We find that, after controlling for relevant factors, second- generation minorities typically have stronger British identities than the white majority, and in a number of cases so also do the first generation. Minorities most commonly have strong dual ethnic and national identities. UK-born minorities are less likely to hold min- ority-only identities than their immigrant counterparts and more likely to hold British-only identities, while the shares with both weak minority and British and strong dual identities remain relatively constant across the generations. There is some variation across ethno-religious groups, with the largest share of strong dual identities being among Indian Sikhs and the smallest among other white and Carib- bean Christian groups. Among the white majority, single English, Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish iden- tities are the most common, with certain exceptions: a sole British identity is dominant among Northern Irish Protestants. Political commitment has no substantial indepen- dent influence on elective identities, unlike socio-demographic factors, possibly suggesting that such attachments represent less civic and more

- 39. ‘ethnic’ nationalism (Smith 1991). We return to these points in our conclusion, where we consider their implications and reflect on the extent to which the specific UK case may also hold lessons for other countries. 2616 A. Nandi and L. Platt Background In the context of increasing immigration and the changing composition of European populations, there has been extensive debate on the consequences of increasingly multicultural societies and the success or otherwise of ‘multiculturalism’ as a political project (Koopmans 2013; Kymlicka 1996). Modood (2007) regards multiculturalism as combining recognition of groups’ difference with assertion of a common national identity, implying the possibility of harmonious dual identities. However, there have been ongoing debates about the extent to which group recognition is compatible with the egalitarian principles of liberal democracies (Barry 2001). Huntington’s (1993) claim that there are limits to the extent that it is possible for different ‘cultures’ to coexist has found resonance in the political retreat from multiculturalism (Koopmans 2013) and anxiety about a fundamental incompatibility between

- 40. difference and shared identity (Verkuyten and Zaremba 2005). For example, in UK political discourse, multiculturalism has been linked with separatism, religious fundamentalism and alienation from core national values (Cameron 2011), with failure to accede to British national identity seen as a particular issue for the second generation of minorities. In the face of strong academic as well as political conviction that national identity is central to social cohesion (Moran 2011; Reeskens and Wright 2014), the quantitative evidence base relating to minority or immigrant national identification and its correlates and consequences has been growing (e.g. Diehl and Schnell 2006; Fischer-Neuman 2014; Georgiadis and Manning 2013; Kesler and Schwartzman 2015; Lam and Smith 2009). Much of the focus has been on the experience of minorities specifically and their in-group or out-group identification. Additionally, some studies have also compared minorities with the majority, and these suggest that immigrant minorities’ national identification is as great as that of the majority, albeit with some variation across groups (Georgiadis and Manning 2013; Karlsen and Nazroo 2013; Manning and Roy 2009; Masella 2013; Reeskens and Wright 2014). A nascent literature on gen- erational change in identity in the UK suggests that across minority groups, the ten- dency is for national identity to increase with time and

- 41. generation, while minority identity declines (Georgiadis and Manning 2013; Guveli and Platt 2011; Karlsen and Nazroo 2013; Manning and Roy 2010; Platt 2014). However, despite these suggestive insights, existing research, both qualitative and quantitative, often includes only partial coverage of ethnic groups, with much of the current literature focusing on Muslim groups and single generations (e.g. Jacobson 1997; Lam and Smith 2009; Vadher and Barrett 2009). Moreover, the focus on minority identity integration or assimilation has tended to obscure the analysis of national iden- tity among the dominant group itself, which has, instead, been the focus of separate study (see e.g. Bechhofer and McCrone 2012; Kiely, McCrone and Bechhofer 2005). However, majority identification is a critical part of the context for minorities: the extent to which minority groups’ identity claims are accepted may impact on the degree to which they feel able to make them (Crul and Schneider 2010). At the same time, shifts in the meaning of national identity resulting from changing national composition may be implicated in the extent to which the majority themselves identify with an overarching polity (Gong 2007). Ethnic and Racial Studies 2617 It is therefore pertinent to contextualize minority diversity

- 42. within the diversity of the majority population identification. Identity acculturation is not a one-sided process (Berry 1997), and the relations implied within the process of assimilation are not singu- lar (Brubaker 2001). The potential of national identity to effectively accommodate min- ority or immigrant groups is an important component of the extent to which minorities can and will identify with it (Moran 2011). While Scottish identity is being recast as a more ‘inclusive’ identity (Bechhofer and McCrone 2012), the ‘rise’ of English identity (Wyn Jones et al. 2012) may herald a redrawing of national boundaries to a more ‘ethnic’ conception of nation (Smith 1991), with consequences for its inclusivity (Reeskens and Wright 2013). We therefore conceptualize minority and majority identity within an acculturation framework that describes the changes that take place in cultural patterns for either group when two differentiated groups come into contact (Berry 1997). In this paper we focus on Berry’s model of psychological acculturation at the level of individual identity, which distinguishes between assimilation, integration, separation and marginalization. While there is considerable debate around concepts of assimilation and integration (Alba and Nee 1997; Brubaker 2001; Rumbaut 1997), whether in relation to structural or cultural domains, Berry’s four-way categorization provides

- 43. us with a widely accepted nomenclature for describing particular intersections on the two axes of ethnic and national identity. Much of the discussion around assimilation has been con- cerned either with distinguishing its normative from its descriptive aspects (see e.g. Brubaker 2001), or assessing whether its predictions do indeed materialize (e.g. Rumbaut 1997). In this paper we use the term assimilation descriptively to define those for whom British national identity predominates. Integration has been subject to similar critiques as ‘assimilation’, although, following Berry’s terminology, we are operationalizing it as representing dual identity. In the same way, separation and marginalization are used as descriptors of predominantly strong ethnic identity, and low national and ethnic identification, respectively. While Berry’s framework is well recognized and has been used in other work on ethnic identity and multiculturalism (see e.g. Diehl and Schnell 2006; Fischer- Neumann 2014; Heath and Demireva 2014), our approach extends existing research in two ways. First, for analysing minority group acculturation, we utilize comparable scaled measures of both national and ethnic identity that are collected independently and tap into affective but individualized dimensions of identity (Phinney 1990). We are thus able to develop previous literature exploring binary measures of national iden- tity that may be associated with legal citizenship (Manning and

- 44. Roy 2010; Platt 2014), and capture a more affective component (Reeskens and Wright 2014). We also are able to focus on identity rather than related concepts such as belonging (Burton, Nandi and Platt 2010), as used, for example by Georgiadis and Manning (2013) and Maxwell (2006), or connection to a particular country (Fischer-Neumann 2014). In operationalizing this framework and investigating patterns of identification, we are adopting a concept of identity that is deemed to be stable at the point of analysis, even though we recognize that identity is contingent and subject to interpretation and hence is differentially adopted and adapted (see e.g. the discussion in Lam and Smith 2009; Verkuyten and Reijerse 2008). As noted by Tajfel (1981), social identity is 2618 A. Nandi and L. Platt formed and expressed under specific historical, cultural and ideological conditions, and the current configuration in the UK marks an interesting case for investigating identities. The second innovation is that we introduce a comparative analysis of the majority population within the same framework as that for minorities. This allows us to engage with the heterogeneity of the majority rather than

- 45. representing it as a mono- lithic, normative reference point. It takes seriously the imperatives of the new assimila- tion theory (Alba and Nee 1997) and of acculturation theory to acknowledge that these processes are two-sided. From the extant literature, we hypothesize that minorities in the UK will have national identities as strong as or stronger than the majority, but that they will vary by group (Georgiadis and Manning 2013; Jaspal and Cinnirella 2013; Manning and Roy 2010; Maxwell 2006). We expect that British national identity will be stronger in the second generation, but will also be sensitive to the responses of the majority (Heath et al. 2013) and hence be reduced by harassment. We also anticipate that national and ethnic identities will be reinforcing, leading to an over-representation of ‘integrated’ (dual) identities. We expect separated (ethnic-only) identities to decline across generations with a commensurate increase in assimilated (British-only) identities. Among the majority, we expect that the key influence on the patterning of identity will be country-specific national-religious origins. Specifically, we anticipate strongest ‘separated’ identification among Scots (Bechhofer and McCrone 2012) and greater attachment to British (integrated or assimilated) identities among Northern Irish Protestants.

- 46. We nevertheless anticipate that socio-demographics will be associated with different identity patterns across both minorities and the majority. Among minorities, those with lower socio-economic status and lower educational levels and those who are older would be expected to have more invested in national (British) identity (Georgiadis and Manning 2013; Maxwell 2006), as those with more privileged positions have had more opportunities to ‘select’ their identities (Kesler and Schwartzman 2015; Nandi and Platt 2012). Among the majority, we anticipate that lower socio-economic status and being older will instead be linked to country-level identities as a more local point of validation. We anticipate that mainstream political engagement is liable to increase investment in assimilated and integrated identities among minorities; while, in the face of greater debate over devolution and country identities (Bechhofer and McCrone 2012), it will be more closely linked to separated identities among the majority. Data and measures Data We use data from Understanding Society, a UK longitudinal survey of a nationally representative sample of approximately 28,000 households, with an additional ethnic minority boost sample (EMB) of around 4,000 households

- 47. (Knies 2014). The EMB contributed around 1,000 adult interviews of five target ethnic minority groups Ethnic and Racial Studies 2619 (Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, black African, Caribbean) in addition to those covered in the main sample. Every year the adult (16+) household members are asked about their lives. In addition to questions on socio-demographic characteristics, the survey includes questions on attitudes and identity, including political beliefs, Britishness, strength of identification with parents’ ethnic group and national identity. Some of these questions (which we call ‘extra questions’) are asked only of (a) the EMB, (b) a comparison sample of 500 households from the main sample, and (c) ethnic min- orities living in ‘low-density’ areas not covered by the EMB. This rich set of identity questions, the representative UK coverage, the large sample size and the EMB makes Understanding Society uniquely suited for this analysis. We use the UK 2011 census question to identify the white majority (as those choos- ing white: British/English/Scottish/Welsh/Northern Irish category) and minority (those choosing any of the other categories) groups. Dependent variables: British, ethnic and national identity

- 48. National identity: The entire sample was asked a standard census question on national identity: respondents selected one or more national identities from English, Welsh, Scottish, Northern Irish, British, Irish and Other. Each could be chosen singly or in combination. British identity: Those eligible for the ‘extra questions’ were asked ‘how important being British’ was to them. They were shown an eleven-point- scale where higher on the scale was ‘more important’ and chose their position on it. Ethnic identity: Minority group members eligible for ‘extra questions’ were additionally asked to give the strength of identification with their father’s ethnic group and with their mother’s ethnic group (if different), using a similar format and eleven-point scale. We use this as our measure of minority ethnic identity, prioritizing the highest score where responses on mother and father differed. Independent variables Ethno-religious group: The ethnic group categories in the 2011 census questions are widely used, but have been criticized for conflating groups with different migration and settlement histories and different patterns of association that are often linked in practice to religious distinctions: for example, Muslims, Sikhs and Hindus of Indian origin (see e.g. Longhi, Nicoletti, and Platt 2013). An

- 49. alternative is to construct ethno-religious groups, which has the additional advantage that it enables the concur- rent incorporation of ethnicity and religious affiliation into the measure. We use reli- gion (current religion or, if no current religion was reported, the religion respondents reported being brought up in) alongside the census ethnic group categories to construct a seventeen-category measure of ethno-religious group.1 Country-community origin: For majority group analysis, we constructed a measure of country-community origins that combined country of birth (whether England, Scot- land, Wales, Northern Ireland or elsewhere2) with religious affiliation/community of upbringing (Catholic, Protestant, or other or none). From this we derived a nine-cat- egory measure that distinguished religion/religious community for Scotland and 2620 A. Nandi and L. Platt Northern Ireland, where it is most likely to be salient for national identity, but not for England, Wales or Other. Other covariates Demographic variables: We include age measured in six bands, and sex, along with marital/cohabitation status, measured as single never married, cohabiting, married or

- 50. in a civil partnership, separated, widowed or divorced. We also include region of residence. UK-born: We include a measure of immigrant generation, identified by whether UK-born (second or subsequent generation) or not (first generation) in the minority group analysis. Socio-economic position: To investigate whether identity varied with socio-econ- omic position, we included measures of highest qualification (four categories), employ- ment status, and occupational class as measured by the eight- category National Statistics Socio-economic Classification (Rose, Pevalin and O’Reilly 2005). Political engagement: We utilize a measure of political party affiliation, both strong and weak, to capture political engagement in the minority group analysis. Given that the vast majority affiliate to one of the UK-wide national parties (see Heath et al. 2013), this takes the form of a seven-category variable of none/not eligible to vote, and strong and weak Conservative, Labour and Other party supporter. In the majority analysis, given that different political parties operate in the different countries of the UK, we use a three-category general measure of political support – whether supporting any party strongly, weakly, or not at all. Harassment: In the minority group analyses, we include a three- category measure of

- 51. no harassment, direct experience of physical or verbal harassment, and feeling unsafe. Analytical approach We first examine our hypotheses that strength of British identity is as great or greater among minorities as among the majority, but with some diversity across groups. As this question was one of the ‘extra questions’, we are left with a sample (Sample 1) of N = 7,762 of whom 14% are white majority. We regress British identity on ethno-religious group and the full set of covariates using ordinary least squares (OLS) regression. Using Sample 1, our reference population for ethno-religious group is white Christian majority. For the analysis of both minority and majority acculturation, we adopt – and adapt – Berry’s four-way acculturation framework. Berry (1997) identified four potential path- ways that behavioural and identity acculturation could take: assimilation, integration, separation and marginalization. As noted, we use these labels as analytical descriptors of particular positions on the two axes of national and ethnic identity rather than as nor- mative categories (see Brubaker 2001). The framework with these labels is illustrated schematically in the top panel of Figure 1. For the analysis of minority acculturation, we allocate minority group individuals to

- 52. the four levels of the quadrant based on the measures of ethnic and British identity. We distinguish strong and weak identification by whether responses fall above or below the Ethnic and Racial Studies 2621 median value. These questions were part of the ‘extra questions’ and we are thus left with a minority-only sample (Sample 2) of N = 6,490. This allocation and the ensuing distribution are illustrated in the second panel of Figure 1.3 While the use of the median is essentially arbitrary (Berry and Sabatier 2010), the fact that it splits the population equally means that if there were no association between the strength of the two iden- tities, we would expect to find 25% of the sample in each cell. If there were a negative relationship between the two identities, there would be over- representation in the assimilated and separated cells. In fact, it is the integrated cell that shows over-rep- resentation, indicating that those who identify strongly on one measure are more likely to identify strongly on the other. We model these four outcomes by estimating a multinomial logistic regression model on our second sample, with ‘separated’ as the reference category, and including the full set of covariates. Figure 1. Measurement of identity acculturation outcomes.

- 53. 2622 A. Nandi and L. Platt To model the white majority’s identity acculturation, we utilize responses to the mul- ticode measure of national identity, described above. We are thus left with a sample (Sample 3) of N = 35,617 white majority respondents. Respondents are allocated to the integrated category if they claim both a British and (English/Welsh/Scottish/North- ern Irish) country-level identity, as separated if they claim a country identity only, assimilated if they claim a British identity only, and marginalized if they do not claim any UK country or British identity. This last group is a small residual group, as the third panel of Figure 1 shows, and includes those who describe their national identity as Irish as well as some who identify with another country, despite claiming white – British/English/Scottish/Welsh/Northern Irish as their ethnic group. Since the allocation is based on a different measure and cannot be constructed to be evenly split across the two axes, it is not directly comparable with the measure of acculturation used in the minority group analysis. Nevertheless, it indicates the priority accorded by the majority to different identity options, which provides important context for the min- ority choices. It also allows investigation of whether predictors of different accultura- tion outcomes are consistent or differ across minorities and the

- 54. majority. We again estimate multinomial logit models for the relative chance of being in the integrated, assimilated, or marginalized categories relative to being in the separated group, exploring differences between country-community origins compared to the reference category of English origins. To facilitate interpretation of the multinomial logistic regressions, we provide tables of predicted probabilities of the four outcomes to illustrate the average marginal effects of certain key predictors of interest, including ethno-religious group and country-com- munity origin. All estimations are weighted using household design weights, and standard errors estimated correctly by accounting for the complex survey design. Descriptive statistics of all variables used in the analysis for each of the three samples are provided in the supplemental material (see Appendix: Table A1). Minority ethnic identity and acculturation We first address the question of how British identity varies across ethno-religious groups. Table 1 shows the results from the full OLS model. After adjusting for covariates, Caribbean Christians, those of mixed ethnicity and the various ‘other’ groups, were not significantly different from the white Christian

- 55. majority in their strength of British identification. Only the other white group had a sig- nificantly less strong British identity while all other ethno- religious groups expressed a stronger British identity. A difference of more than one point on the eleven-point scale was found for Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, black African Muslims and Indian Sikhs and less than one point for Indian Hindus and black African Christians. These differ- ences are consistent with our hypotheses derived from related literature using different data and measures. Notably, however, here we use a direct measure of national identity that better reflects its conceptualization in the literature, and a more fine-grained and comprehensive ethnic group categorization that reveals consistency but also differ- ences within the Indian population as well as the high British identification of black African Christians. Some of the difference in British identification between ethno- Ethnic and Racial Studies 2623 Table 1. OLS estimates of a model of strength of British identity. With political affiliation Without political affiliation

- 56. Coefficient SE Coefficient SE Age group (omitted: 40–49 years) 16–19 years −0.44* 0.25 −0.57** 0.25 20–29 years −0.66*** 0.16 −0.76*** 0.17 30–39 years −0.25* 0.14 −0.30** 0.14 50–59 years 0.54*** 0.16 0.60*** 0.16 60+ years 0.53*** 0.18 0.73*** 0.18 Female 0.01 0.09 −0.03 0.10 Region of residence (omitted: London) North −0.13 0.14 −0.15 0.14 Midlands −0.19 0.14 −0.22 0.14 East, South −0.49*** 0.14 −0.49*** 0.14 Wales −0.29 0.36 −0.29 0.37 Scotland −1.68*** 0.30 −1.74*** 0.31 Area of low ethnic minority density −0.08 0.13 −0.13 0.14 Current marital status (omitted: never married) Cohabiting as a couple 0.12 0.22 0.16 0.22 Married or in a civil partnership 0.18 0.14 0.22 0.14 Separated, divorced or widowed 0.00 0.18 0.03 0.19 Highest educational qualification (omitted: university degree or higher) No educational qualifications 0.56*** 0.16 0.48*** 0.17 O levels or equivalent 0.44*** 0.14 0.41*** 0.14 A levels or equivalent, diploma 0.38*** 0.13 0.39*** 0.14 Current employment or main activity status (omitted: employed) Not employed 0.10 0.14 0.09 0.14 Taking care of family −0.29 0.18 −0.27 0.18 Full-time student −0.38* 0.20 −0.34 0.21 NS-SEC (omitted: routine) Large employers and higher management −0.19 0.28 −0.09 0.29 Higher professional −0.48** 0.24 −0.44* 0.24 Lower management and professional 0.01 0.19 0.05 0.19 Intermediate −0.16 0.20 −0.09 0.20 Small employers and own account −0.15 0.24 −0.14 0.25 Lower supervisory and technical −0.17 0.24 −0.17 0.24

- 57. Semi-routine 0.28* 0.17 0.27 0.17 Never worked and long-term unemployed 0.38** 0.18 0.32* 0.18 Political beliefs (omitted: none, don’t know or can’t vote) Conservative party, strong supporter 1.42*** 0.21 Conservative party, not very strong supporter 0.99*** 0.16 Labour party, strong supporter 1.03*** 0.13 Labour party, not very strong supporter 0.58*** 0.12 Other party, strong supporter 0.13 0.27 Other party, not very strong supporter 0.26 0.17 Harassment experience last year (omitted: none) Was physically attacked or verbally insulted −0.28** 0.12 −0.24** 0.12 Avoided or felt unsafe −0.02 0.11 0.00 0.11 Born in UK 0.74*** 0.13 0.80*** 0.14 (Continued) 2624 A. Nandi and L. Platt religious groups is explained by differences in their political affiliation and support. Once the political support variable was included, ethno- religious group coefficients were attenuated. Political support, whether strong or weak, for either of the two main political parties (Labour and Conservative) was positively associated with British identification, although this was not the case for support for an alternative party. This suggests that engagement with national politics reinforces feelings of being part of the nation, but only when that engagement is mainstream.

- 58. Being UK-born was positively associated with British identification, as expected. In addition, higher qualifications,4 being from a professional occupation, being younger and being a student were negatively associated with Britishness, while a semi- routine or routine occupation or being long-term unemployed were positively associ- ated, illustrating the greater salience of national identity in the absence of competing professional identities, in line with our hypotheses. Congruent with expectations, experience of harassment was negatively associated with British identity. This analysis is not, however, informative about the relationship between British and ethnic identity. For that, we turn to our multinomial logit model of identity accultura- tion among the minority groups. Table 2 illustrates predicted probabilities of the four acculturation outcomes deriving from the average marginal effects of the multinomial logit of certain key characteristics of interest.5 (Full model estimates available on request.) Table 1. Continued. With political affiliation Without political affiliation

- 59. Coefficient SE Coefficient SE Ethno-religious groups (omitted: white Christian majority) Caribbean Christian 0.09 0.20 0.03 0.20 African Christian 0.51** 0.24 0.60** 0.25 Other ethnic group Christian −0.37 0.29 −0.4 0.30 Indian Muslim 1.33*** 0.30 1.36*** 0.30 Pakistani Muslim 1.14*** 0.20 1.15*** 0.20 Bangladeshi Muslim 1.10*** 0.21 1.14*** 0.22 African Muslim 1.14*** 0.29 1.15*** 0.29 Arab-Turkey Muslim 0.69 0.52 0.54 0.55 Indian Hindu 0.72*** 0.22 0.70*** 0.23 Indian Sikh 1.15*** 0.24 1.23*** 0.25 White majority, No religion −0.17 0.24 −0.3 0.25 Chinese no religion −0.11 0.42 −0.32 0.43 Other ethnic group no religion −0.18 0.38 −0.34 0.38 Other ethnic/religious combinations 0.25 0.20 0.14 0.21 Mixed −0.07 0.22 −0.13 0.22 Other white −1.50*** 0.40 −1.61*** 0.41 Constant 5.86*** 0.30 6.35*** 0.30 N 7,762 7,762 Notes: NS-SEC, National Statistics Socio-economic Cassification. Weighted using household design weights; standard errors estimated correctly by accounting for the complex survey design. NS-SEC: National Statistics Socio-economic classification. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Ethnic and Racial Studies 2625 Table 2 shows that across ethnic groups and generations, integrated (dual identity) is the most common outcome in almost all cases. The full table

- 60. (not illustrated) showed that integrated outcomes also tend to be associated with those factors that we hypoth- esized would be particularly associated with positive national identification, such as lower qualifications levels and a poorer employment situation, and which were found to be associated with British identity in the initial analysis. Despite the substan- tial focus in the literature on Muslim identities (see e.g. Guveli and Platt 2011; Karlsen and Nazroo 2013; Koopmans 2013; Verkuyten and Yildiz 2007), there is no evidence that Pakistani Muslims are more likely to have a separated identity or less likely to have an integrated identity than other groups. The exception to predominance of integrated identities is among those of other white backgrounds, for which ‘marginalized’ (weak ethnic and British identity) is the most frequent outcome. Other white is a composite group that contains multiple ‘white’ origins. Nevertheless, these findings speak to the greater independence from commit- ment to ethnic or national identity offered by the greater flexibility and transnational opportunities experienced by those of most other white backgrounds, whether of EU, North American or Antipodean origins. Caribbeans, although coming from a very different migration context, have a similar pattern of relatively low integrated acculturation outcomes to the other white group (although for them it is still the most likely outcome) and

- 61. relatively high rates of mar- ginalized identities across generations, higher than would come from random allo- cation. This is consistent with the findings on relative alienation found by Heath and Demireva (2014), and is a potential concern if strong identity in at least in one of the domains is important for psychological well-being. Having a solely strong British identity (‘assimilated’) is less common, as expected, among first-generation minorities, but increases in the second generation to around one in five for most groups. Correspondingly, separated (strong ethnic only) identities are more common in the first generation and decline among the UK-born, although they still constitute between one in eight and one in five of most groups. These indi- viduals are those who, controlling for background characteristics, might be con- sidered to have failed to take on and accord with the ‘national story’ of their country of birth and residence. However, the overall distributions are partly an arte- fact of the distinction between ‘high’ and ‘low’ at the median: and the rates are still lower than would be expected from random allocation (which would give 25% in each category). For those second generation minorities who are ‘separated’, there is no particu- larly ethno-religious group pattern, with Caribbean and African Christians, Indian Hindus and Chinese with no religion the most likely to be in

- 62. this position. While the rates of marginalization show variation across groups, there is relative stability over generations. Against expectations, marginalization does not therefore appear to be a particular issue of the second generation but is more group- than generation- specific. Table 2 also illustrates the extent to which identity acculturation varies with political engagement. Both strong Labour and Conservative support are associated with higher rates of integrated identities, other things being equal. Having no political beliefs or engagement is, conversely, associated with higher rates of separated identities. This 2626 A. Nandi and L. Platt Table 2. Estimates of acculturation outcomes from fully adjusted multinomial model, by ethno- religious group and (migrant) generation and political affiliation and sex (N = 6,490). Separated Integrated Assimilated Marginalized First generation Pakistani Muslim (ref) 0.19 0.51 0.10 0.20 Caribbean Christian 0.27 0.34 0.09 0.30 African Christian 0.29 0.43 0.10 0.17 Other ethnic group Christian 0.29 0.36 0.08 0.27 Indian Muslim 0.17 0.48 0.18 0.16 Bangladeshi Muslim 0.22 0.49 0.10 0.18

- 63. African Muslim 0.24 0.49 0.09 0.18 Arab-Turkey Muslim 0.24 0.48 0.06 0.22 Indian Hindu 0.28 0.48 0.08 0.16 Indian Sikh 0.23 0.55 0.10 0.12 Chinese no religion 0.32 0.41 0.04 0.23 Other ethnic group No religion 0.22 0.28 0.10 0.41 Other ethnic/religious combinations 0.29 0.37 0.12 0.22 Mixed parentage 0.19 0.34 0.11 0.37 Other white 0.32 0.26 0.04 0.38 UK-born minorities Pakistani Muslim (ref) 0.13 0.49 0.19 0.19 Caribbean Christian 0.19 0.34 0.17 0.29 African Christian 0.21 0.42 0.20 0.17 Other ethnic group Christian 0.21 0.36 0.17 0.26 Indian Muslim 0.11 0.43 0.32 0.14 Bangladeshi Muslim 0.16 0.47 0.20 0.18 African Muslim 0.17 0.48 0.17 0.18 Arab-Turkey Muslim 0.18 0.48 0.12 0.22 Indian Hindu 0.20 0.48 0.16 0.15 Indian Sikh 0.16 0.54 0.18 0.12 Chinese no religion 0.24 0.44 0.08 0.24 Other ethnic group No religion 0.15 0.27 0.18 0.39 Other ethnic-religious combinations 0.20 0.36 0.23 0.21 Mixed parentage 0.13 0.32 0.20 0.35 Other white 0.24 0.27 0.09 0.40 Men No beliefs, don’t know, cannot vote (ref) 0.25 0.36 0.12 0.27 Conservative, strong support 0.15 0.49 0.14 0.21 Conservative, not very strong support 0.16 0.37 0.19 0.28 Labour, strong support 0.20 0.47 0.16 0.17 Labour, not very strong support 0.23 0.42 0.13 0.23 Other party, strong support 0.12 0.42 0.11 0.34 Other, not very strong support 0.17 0.34 0.17 0.32 Women No beliefs, don’t know, cannot vote (ref) 0.29 0.39 0.09 0.24 Conservative, strong support 0.17 0.53 0.11 0.19

- 64. Conservative, not very strong support 0.19 0.41 0.15 0.25 Labour, strong support 0.23 0.51 0.12 0.14 Labour, not very strong support 0.26 0.45 0.10 0.20 (Continued) Ethnic and Racial Studies 2627 enhances the findings from the British identity analysis, since it shows how it is primar- ily strong dual identities, rather than simply strong British identities, that are associated with political commitment and engagement. We now turn to the patterns among the white majority. Majority population and identity acculturation Table 3 shows predicted probabilities for particular characteristics from the full multi- nomial logit model of white majority identity acculturation. (Full model estimates available on request.) Table 3 shows that, controlling for covariates, almost all country-community groups select a separated (country-only) identity as their modal choice. That is, given the option to select a single British or country identity or a multiple identity, most selected a single country. The exception, in line with expectations, is Northern Irish Protestants, Table 2. Continued.

- 65. Separated Integrated Assimilated Marginalized Other party, strong support 0.14 0.46 0.09 0.31 Other, not very strong support 0.20 0.38 0.13 0.29 Note: Estimates derived from full model and at mean values of other covariates. Weighted using household design weights; standard errors estimated correctly by accounting for the complex survey design. Statistics indicated in bold are differences from (italicized) reference categories that are statistically significant at the 5% level of significance. Table 3. Acculturation patterns among the white majority by country/community of origin and political support and sex (N = 35,617). Separated Integrated Assimilated Marginalized English (ref) 0.52 0.24 0.23 0.004 Scottish Protestant 0.60 0.27 0.13 0.003 Scottish Catholic 0.65 0.25 0.10 0.002 Welsh 0.63 0.24 0.13 0.000 Northern Irish Protestant 0.30 0.22 0.48 0.004 Northern Irish Catholic 0.72 0.05 0.17 0.053 Other country of birth 0.39 0.13 0.45 0.032 Men No political affiliation, cannot vote (ref) 0.59 0.21 0.20 0.004 Not strong political party support 0.56 0.24 0.20 0.004 Strong political party support 0.57 0.22 0.21 0.004 Women No political affiliation, cannot vote (ref) 0.53 0.23 0.24 0.003 Not strong political party support 0.50 0.26 0.23 0.003 Strong political party support 0.51 0.24 0.25 0.003 Note: Estimates at mean values of other covariates, deriving