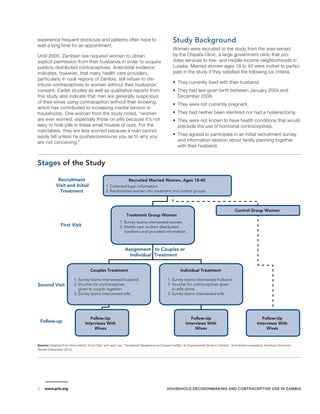

This document summarizes a study on household decision-making and contraceptive use in Zambia. The study found that unmet need for family planning remains high in Zambia, despite available services. It investigated how a husband's role in decisions influences a wife's contraceptive use. Women were given vouchers for free contraception either with their husbands (couples treatment) or privately (individual treatment). The couples treatment led to 25% fewer women using concealable contraception compared to the individual treatment. The study suggests spousal disagreement can impact contraceptive use and fertility outcomes.