1) Propositional functions are propositions that contain variables and have no truth value until the variables are assigned values or quantified.

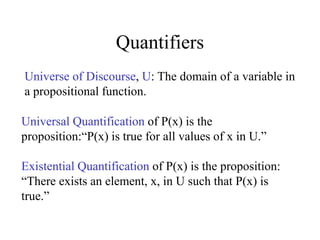

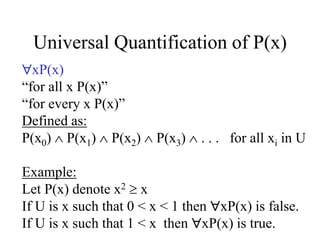

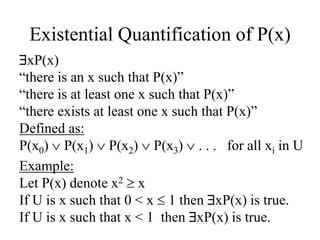

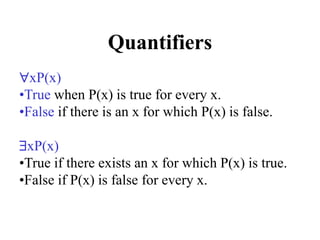

2) Quantifiers like "for all" (universal quantification) and "there exists" (existential quantification) are used to bind variables and give propositional functions truth values.

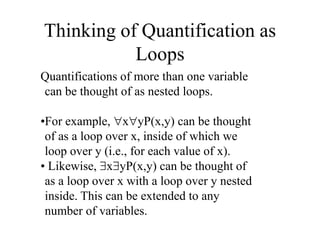

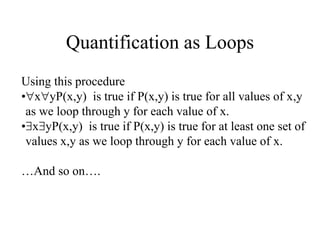

3) Quantification can be thought of as nested loops over variables, with universal quantification checking for truth at each value and existential checking for at least one true value.

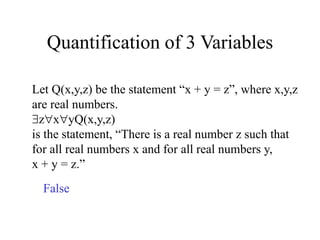

![Assignment of values

Let Q(x,y) denote “x + y = 7”.

Each of the following can be determined as T or F.

Q(4,3)

Q(3,2)

Q(4,3) Q(3,2)

[Q(4,3) Q(3,2)]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/x02predcalculus-230719155212-331211cd/85/X02PredCalculus-ppt-3-320.jpg)

![Examples 3b2

There is exactly one person whom everybody loves.

xyL(y,x)?

No. There could be more than one person everybody

loves

x{yL(y,x) w[(yL(y,w)) w=x]}

If there are, say, two values x1 and x2 (or more) for

which L(y,x) is true, the proposition is false.

x{yL(y,x) w[(yL(y,w)) w=x]}?

xw[(y L(y,w)) w=x]?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/x02predcalculus-230719155212-331211cd/85/X02PredCalculus-ppt-17-320.jpg)

![Examples 3c

There are exactly two people whom Lynn loves.

x y{xy L(Lynn,x) L(Lynn,y)}?

No.

x y{xy L(Lynn,x) L(Lynn,y) z[L(Lynn,z)

(z=x z=y)]}

Everyone loves himself or herself.

xL(x,x)

There is someone who loves no one besides himself or

herself.

xy(L(x,y) x=y)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/x02predcalculus-230719155212-331211cd/85/X02PredCalculus-ppt-18-320.jpg)