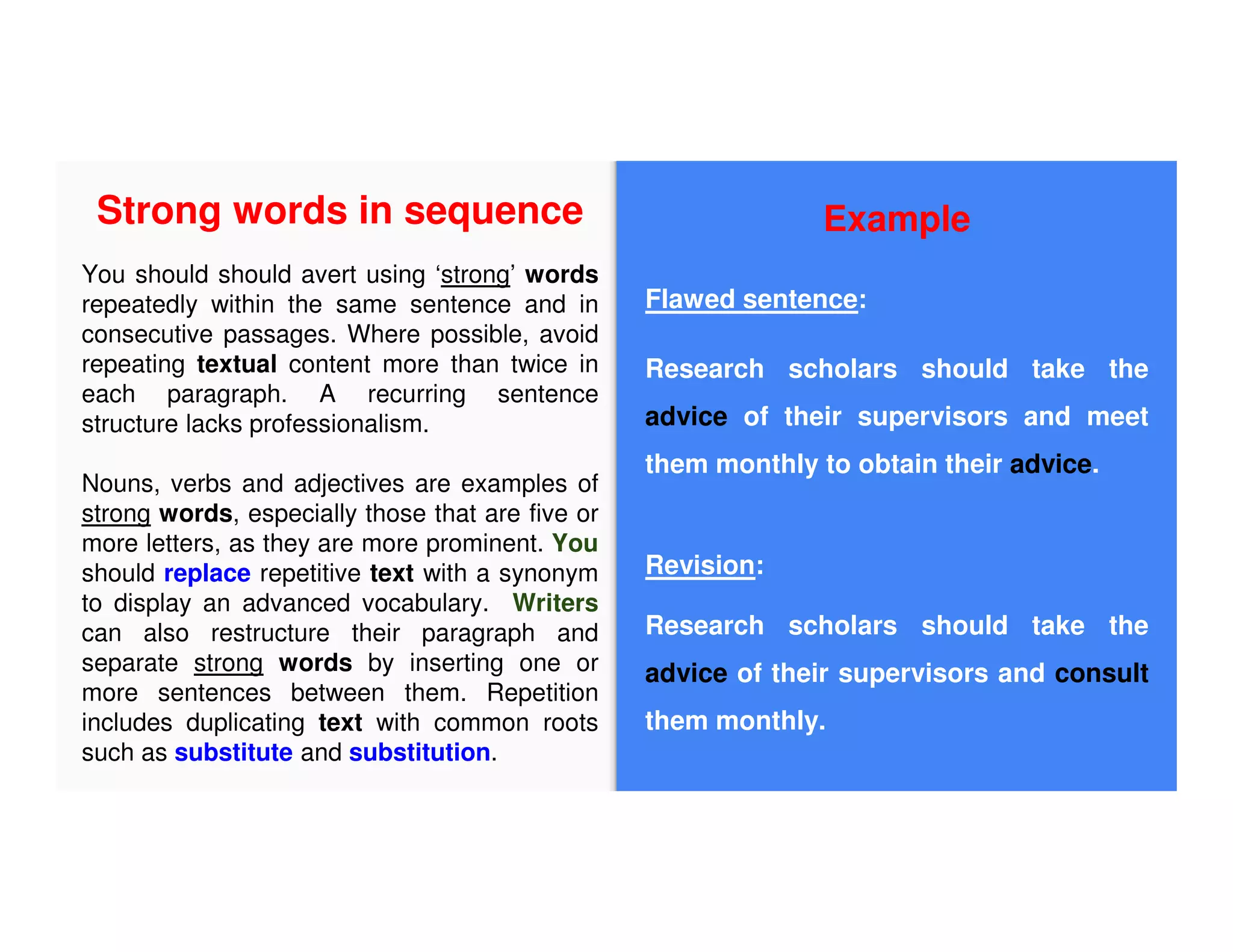

This document provides 14 suggestions for avoiding common pitfalls when writing a thesis or dissertation. Some key points include avoiding run-on sentences, circular arguments, repetition, and disconnected passages between paragraphs. Conceptual discussion grounded in theory is important. The writer should explicitly state the original contributions of their own work. Chapters should be similarly sized and examples should be used appropriately in introductory or data analysis chapters.