The document discusses the history of forest management and fire suppression in western forests. It notes that frequent, small surface fires were historically important for maintaining healthy ponderosa pine forests, but over a century of fire suppression has depleted these natural biological processes. Some forest management professionals now endorse controlled burning and thinning to restore more natural fire regimes. The document also discusses challenges around the wildland-urban interface, where increasing development meets forested areas, posing fire risks. It reviews debates around post-fire logging and its potential impacts on forest restoration.

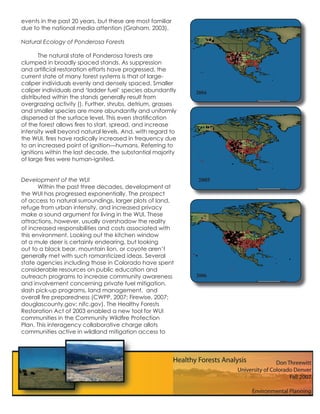

![2007). While the results of this study were initially contended in the peer review process, the data

presented has been validated. Others have analyzed soil restoration after fire events, and found

reduced organic deposits, higher rates of erosion, compaction and dramatically reduced nutrient

loads, which support the theory of hindered restorative growth (Dumroese et al, 2006; Poff, 1996).

Dumroese’s work suggests that harvesting activity in the winter months could diminish erosion,

compaction and possibly minimize disturbance to nutrient loads within post-fire soils.

The current U. S. Forest Service policy on post-event logging allows commencement without

the existing bureaucratic controls in events of emergency economic loss. While the economic

viability of burned timber is not debatable, the expedited process by which access is granted for

harvest prior to decay is a point of contention. Several have argued that this policy is antagonistic

to the protection of wildlife populations already threatened or displaced (Nappi et al, 2004). In

extrapolation of the Dumroese’s work, up to a year’s delay in order to harvest appropriately should

allow ample time for an environmental assessment to occur prior to total stand decay.

Slash: community burden or entrepreneurial windfall

With forest thinning and the substantial slash created resulting from fuel reduction policies, the

problem of surface fuel density arose. Research has shown that thinning without burning or total slash

removal will actually increase the likelihood of fire as well as inhibit healthy growth and regeneration

(Robbins, 2006; Donato et al, 2007). Recently, cottage industries dedicated to processing low-value

timber have appeared--utilizing small diameter trees and slash for several marketable products.

The largest processor currently is Forest Energy Products, a manufacturer of wood pellets for home

heating. One amicable partnership is retrieving enough biomass to supply 25% of the fuel for a local

energy plant (Neary and Zieroth, 2007). The bulk of the responsibility for the bulk of the detrium,

however, still falls on the community (Farnsworth et al, 2002; Iverson and Demarck, 2005; GAO, 2006;

Vogt et al, 2005; Reams et al, 2005). In Perry Park, Colorado, residents log 2000 hours annually in slash

management on their small residential properties alone. The metropolitan district contracts mitigation

in public lands and rights-of-way, and the community is consistently engaged with local agencies to

manage the perimeters of State and National forest lands abutting the community (Threewitt and

Wagonlander, 2006).

Contracting: sound business or old-school business

Currently, approximately 30% of timber managment is contracted either through the BLM or

the Forest Service. According to the 1Q 2007 Healthy Forests and Rangelands report: “Stewardship

contracting...shift[s] the focus of federal forest and rangeland management towards a desired future

resource condition. They are also a means for federal agencies to contribute to the development](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/wildfire-final-report-130130115331-phpapp01/85/Wildfire-final-report-6-320.jpg)