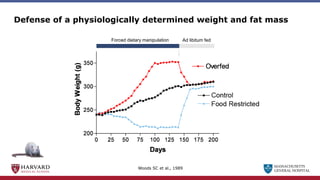

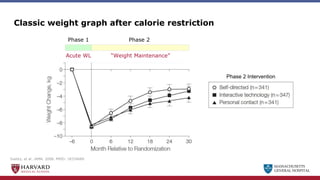

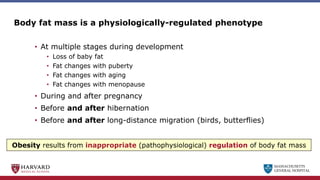

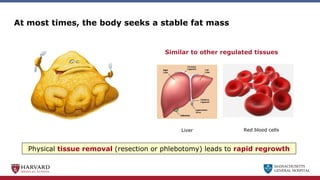

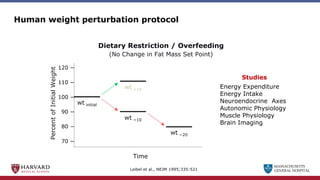

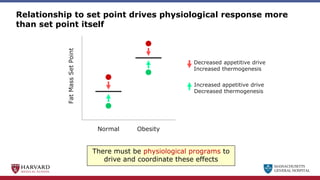

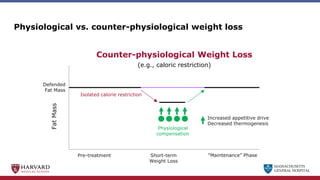

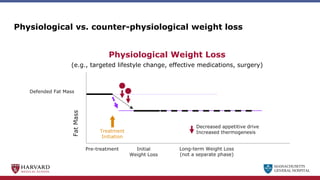

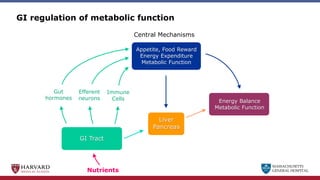

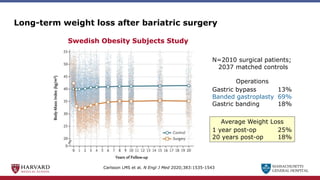

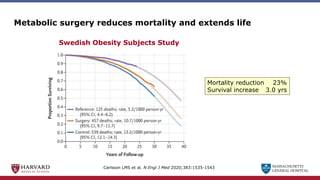

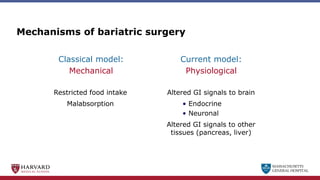

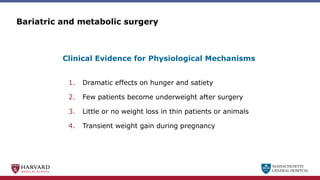

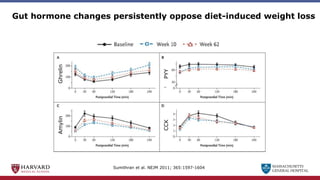

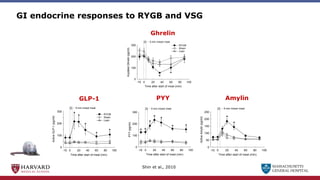

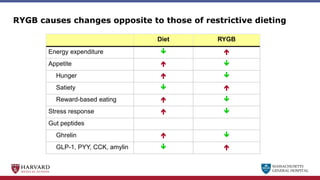

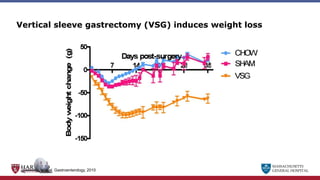

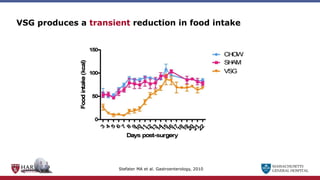

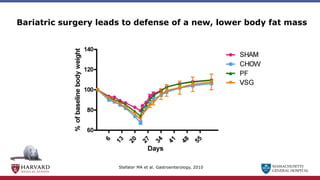

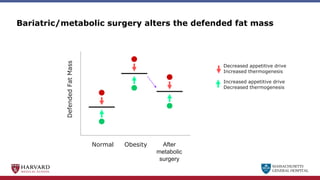

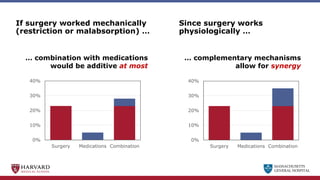

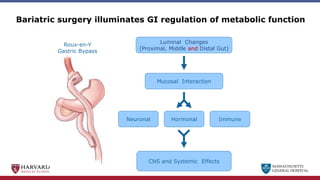

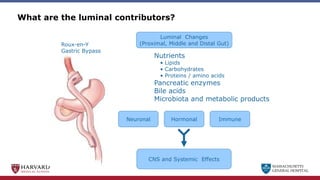

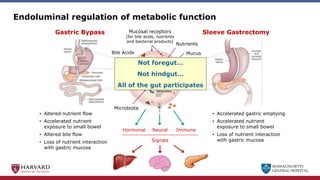

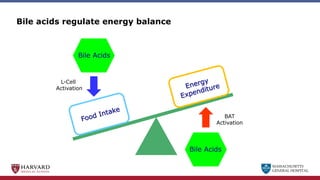

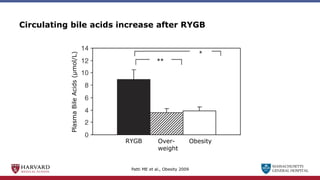

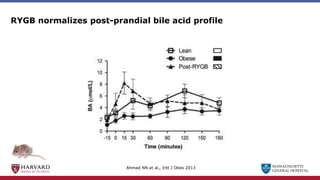

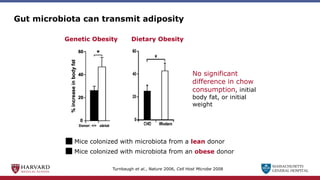

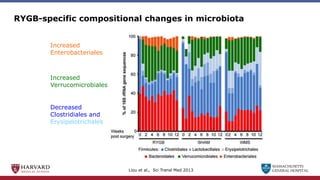

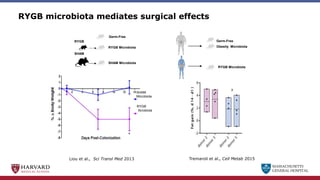

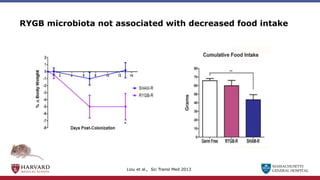

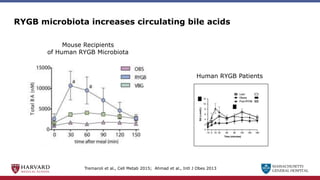

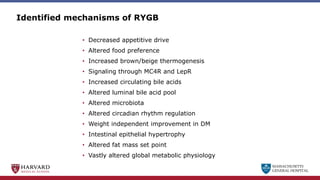

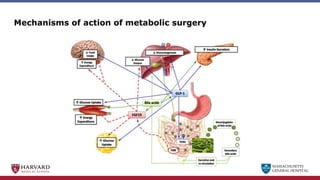

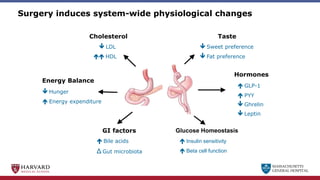

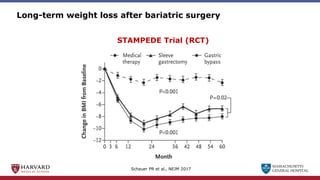

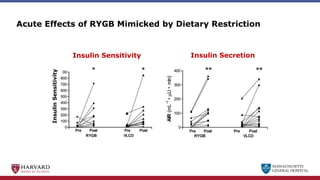

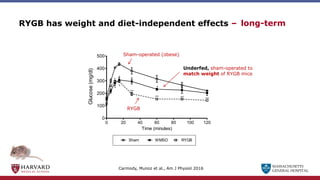

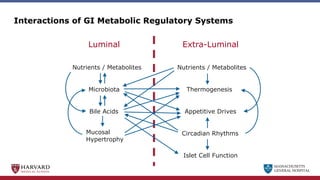

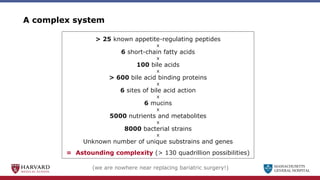

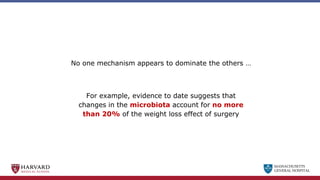

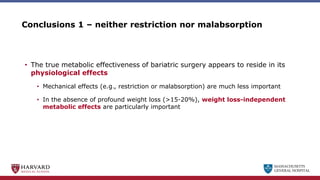

Bariatric surgery leads to long-term weight loss and improved health outcomes through physiological rather than mechanical mechanisms. It alters gastrointestinal signals that change the body's defended fat mass set point and regulate appetite and metabolism. Specifically, surgery modifies the luminal environment and gut microbiota composition, increasing circulating bile acids and triggering hormonal and neuronal signals that decrease hunger and food reward while increasing energy expenditure. This physiological reprogramming opposes the effects of dieting and underlies the durable benefits of bariatric procedures.