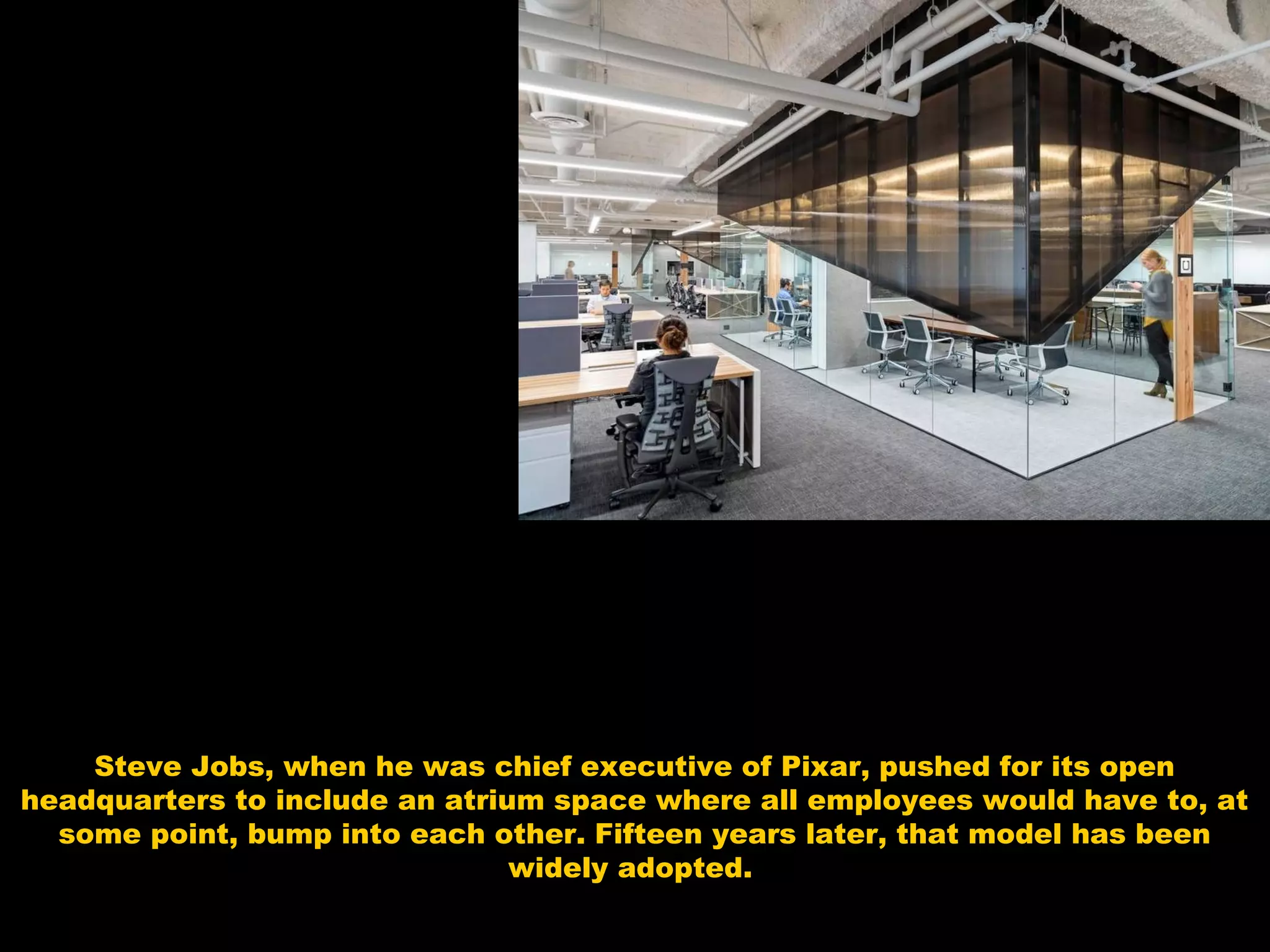

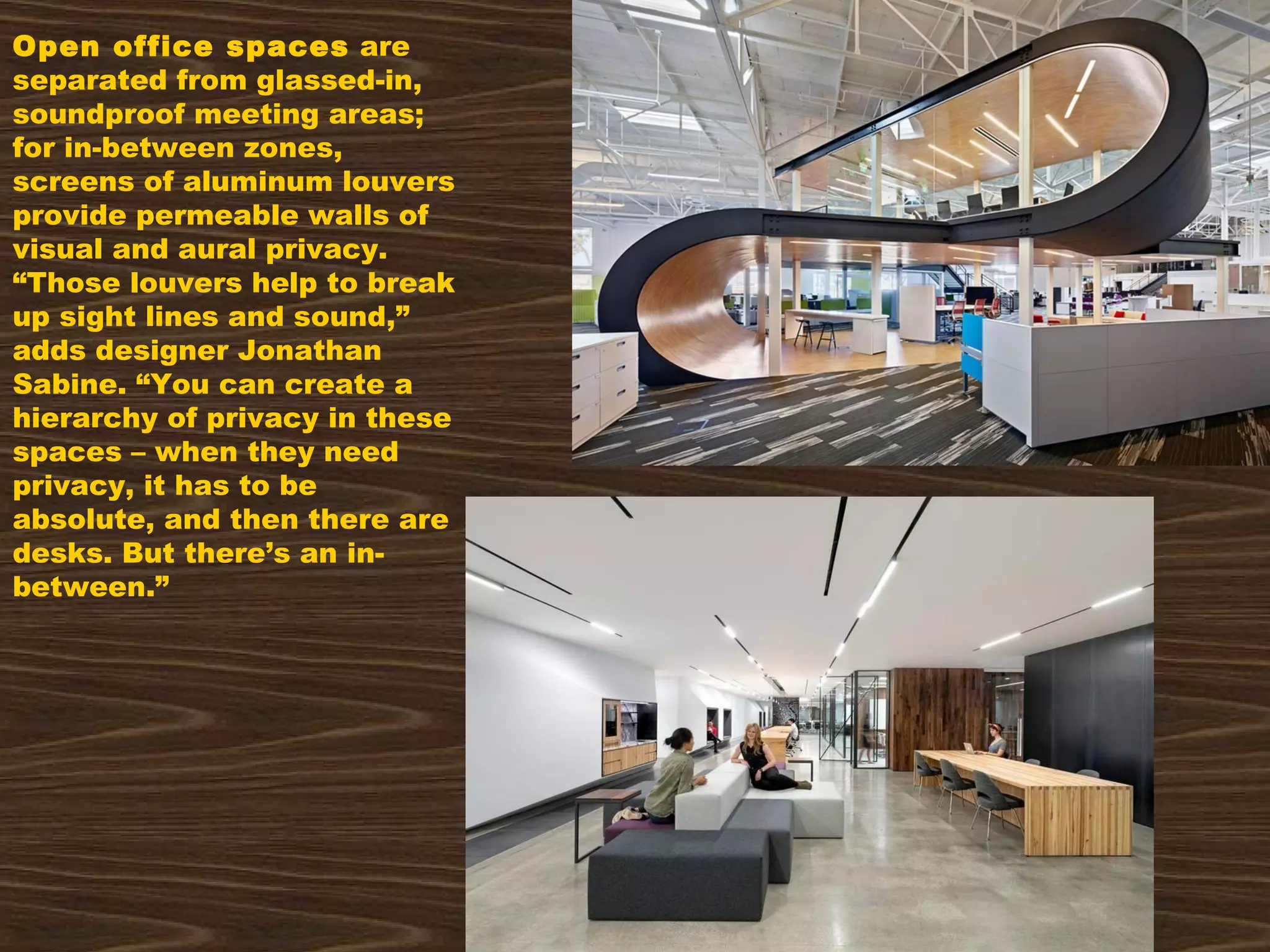

This document discusses the history and challenges of office design, specifically balancing collaboration and individual focus/concentration. It notes that in the 1960s, some saw traditional desks as stifling creativity. Over the past 40 years, there has been no clear resolution to this tension. Modern offices try to provide spaces to accommodate both individual work and collaboration, through methods like open floor plans with separate meeting rooms, work "caves", and adjustable privacy screens. The goal is to allow employees flexibility in balancing solitary and group work.