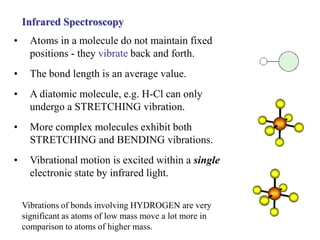

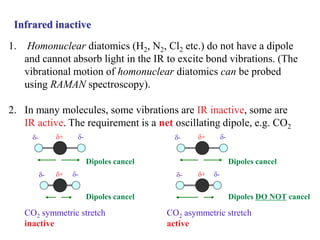

This document discusses infrared spectroscopy and its applications to analyzing molecular vibrations. It begins by explaining that atoms in molecules vibrate and infrared light can excite vibrational motions. Diatomic molecules undergo stretching vibrations, while more complex molecules also bend. The vibrational frequency depends on the force constant and reduced mass. Infrared spectroscopy can identify functional groups and provide information about molecular structure and conformation. It discusses using the amide I and amide II bands to analyze secondary structure in proteins.