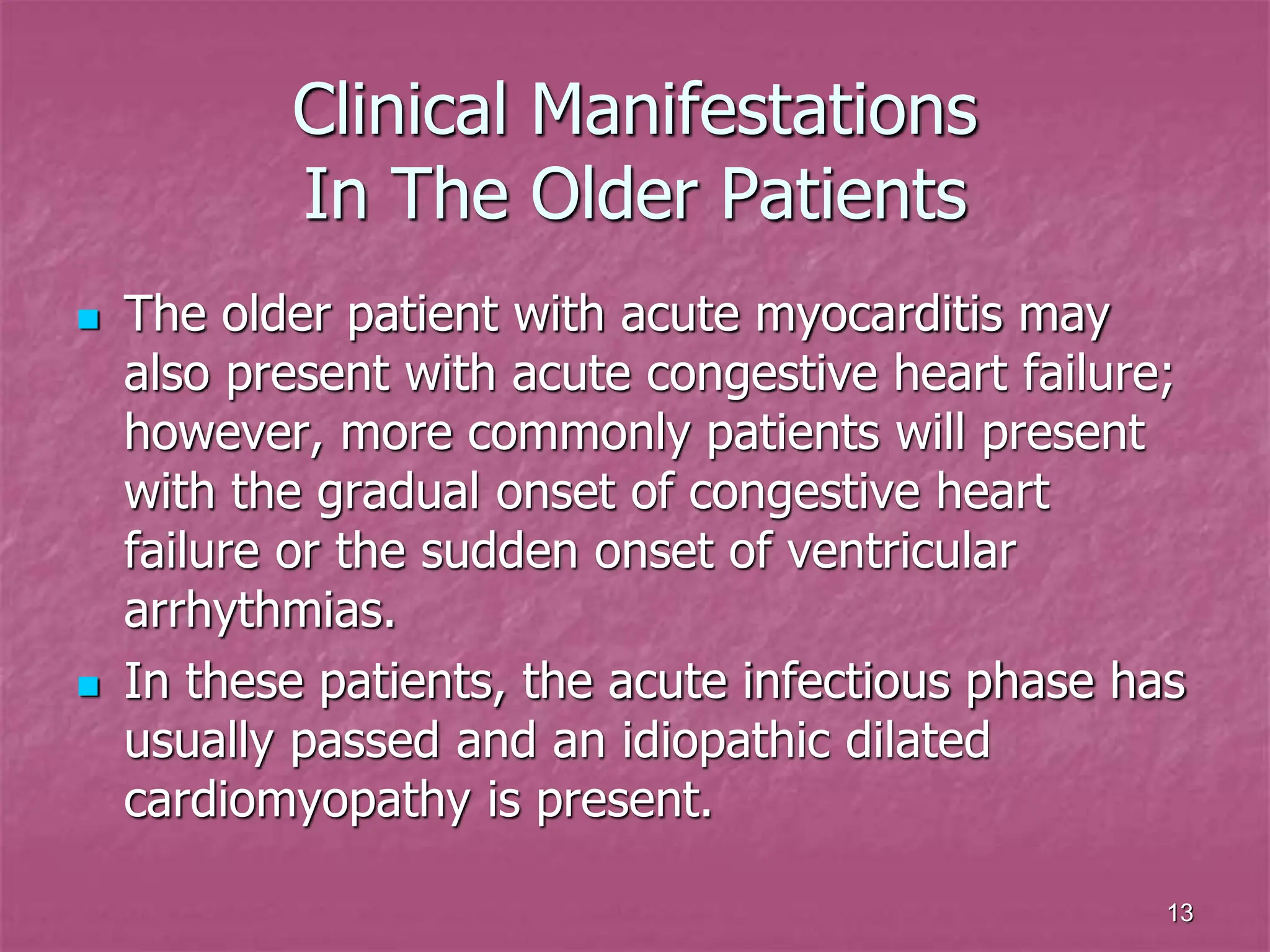

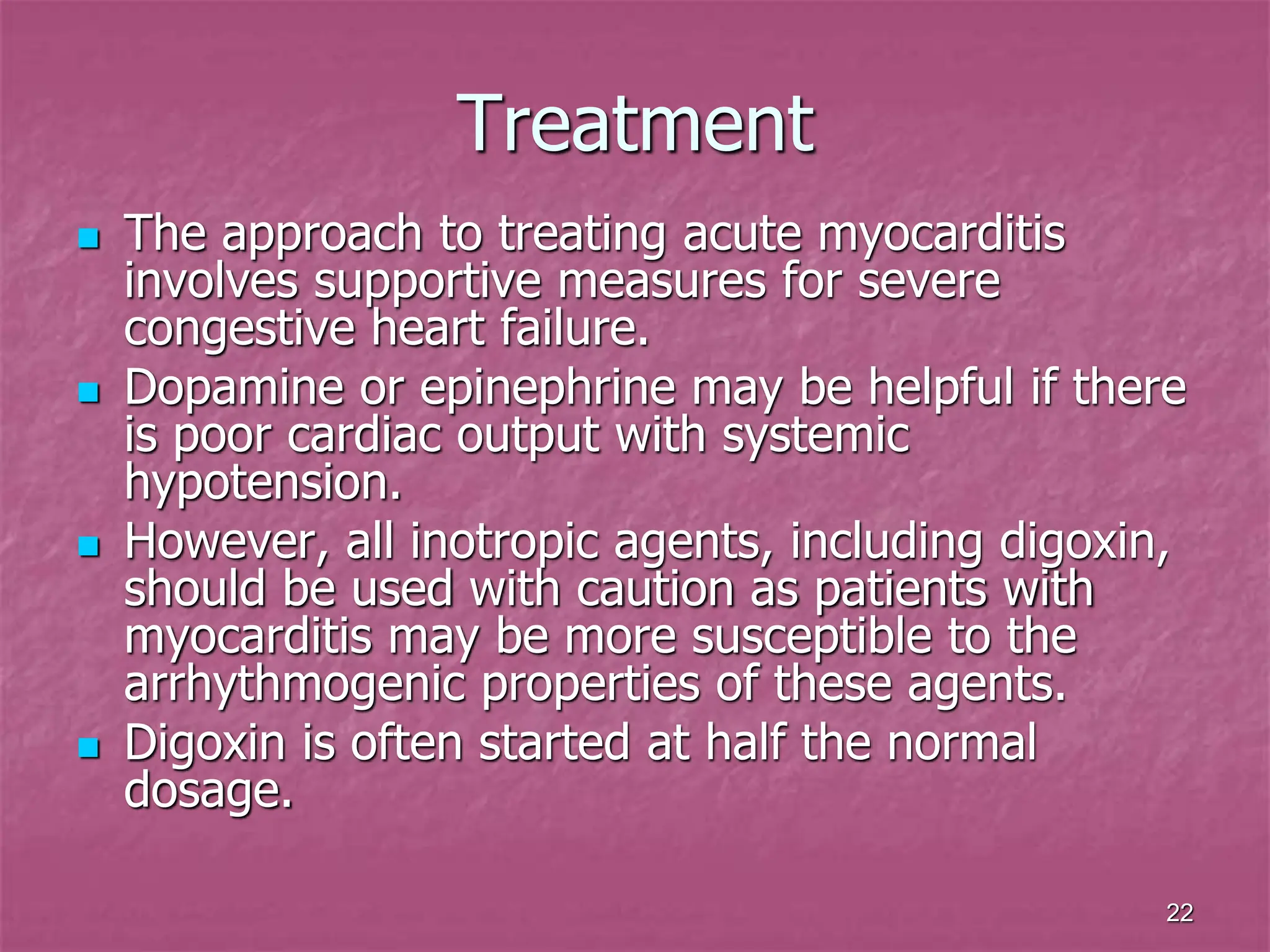

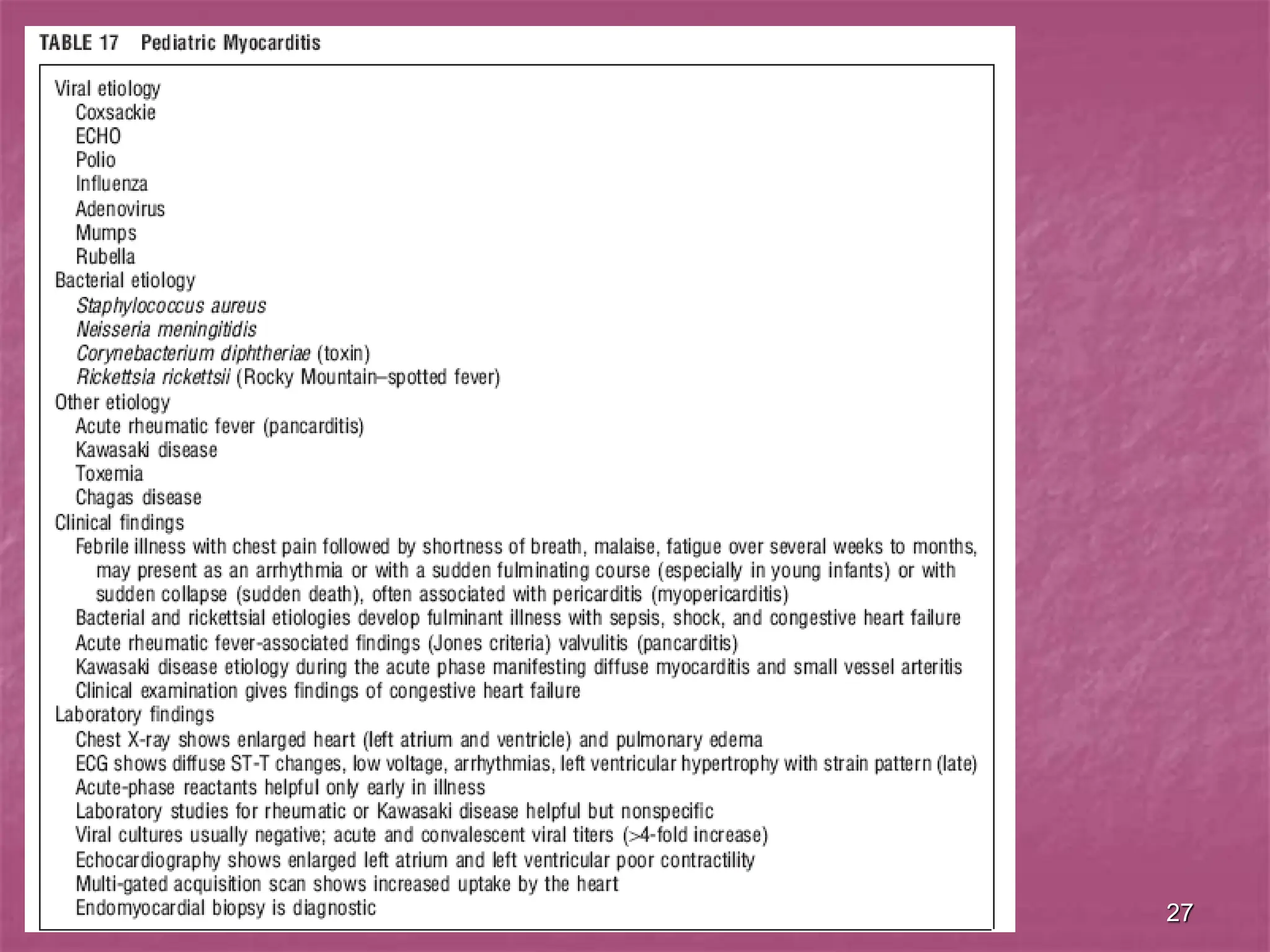

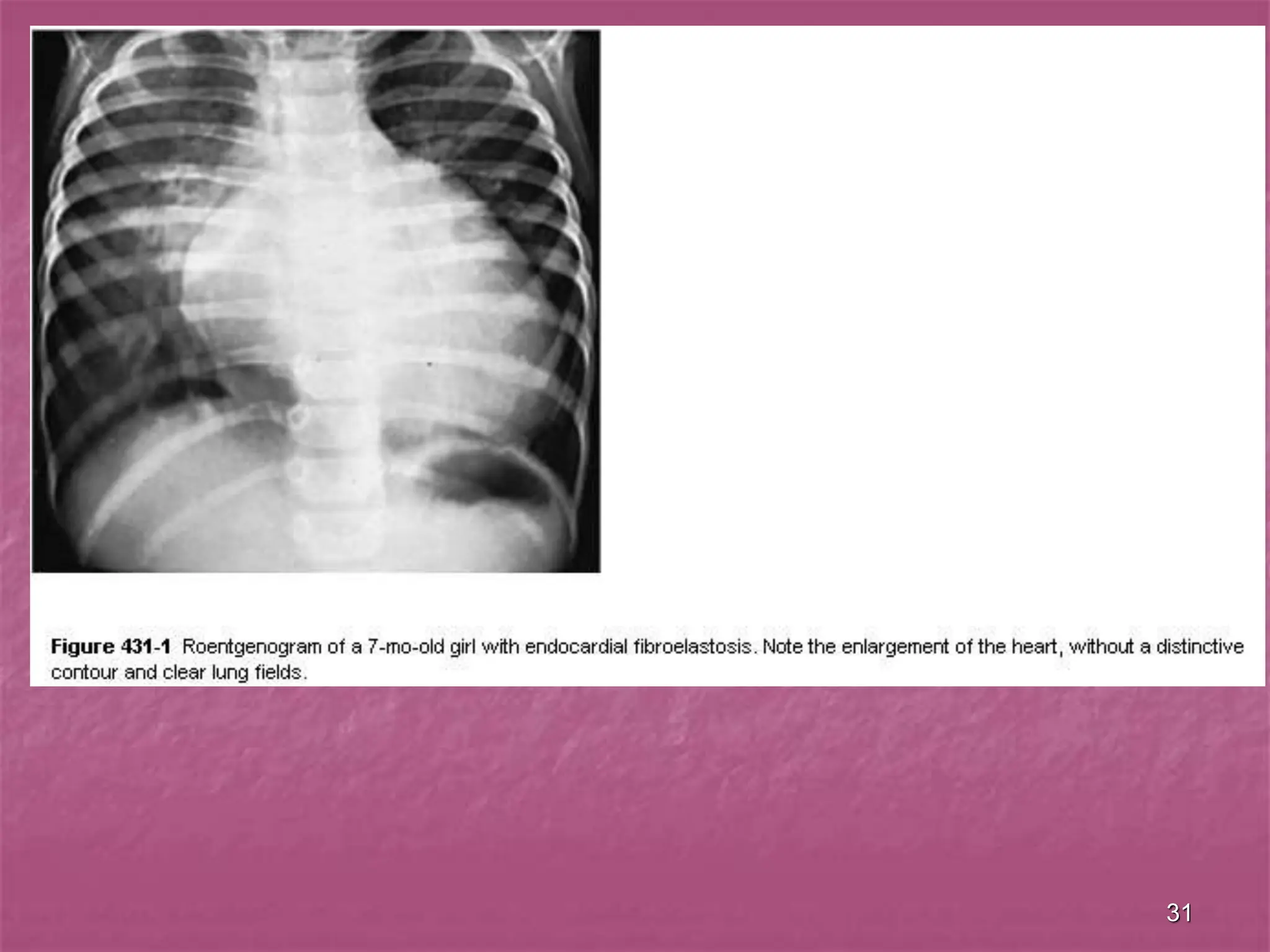

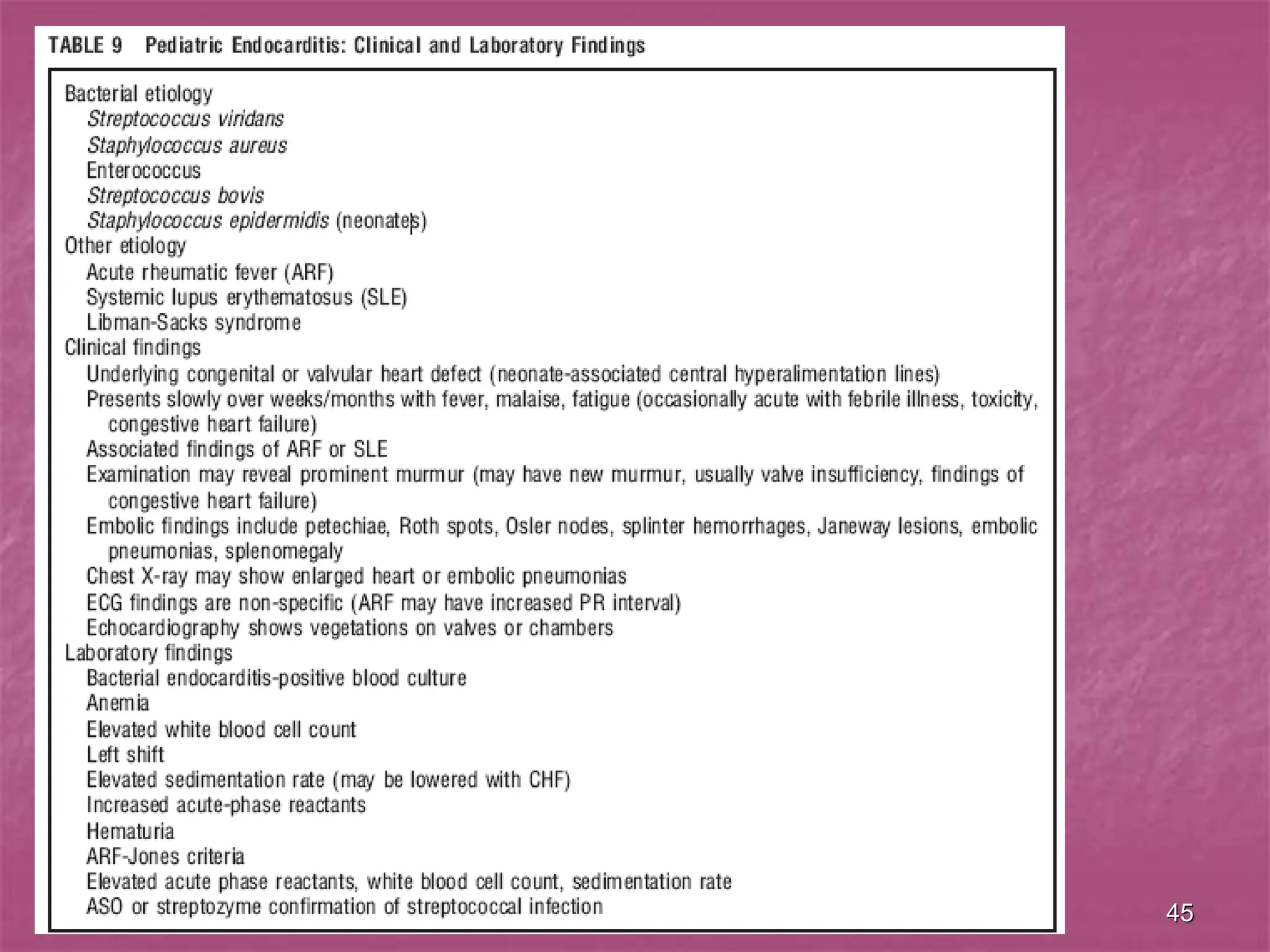

The document discusses viral myocarditis, its causes, symptoms, and clinical outcomes in children, highlighting that it often presents with severe heart failure, especially in neonates. It explains the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment options, along with the prognosis for affected patients, emphasizing a poor outcome for symptomatic neonates and those with chronic conditions. Additionally, it touches upon related conditions like endocardial fibroelastosis and myocardiodystrophy, detailing their clinical significance and management strategies.