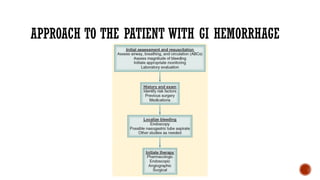

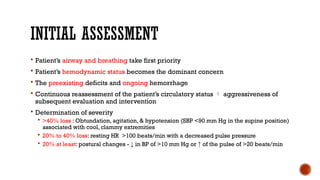

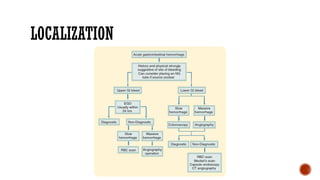

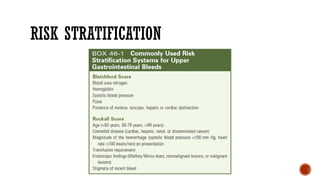

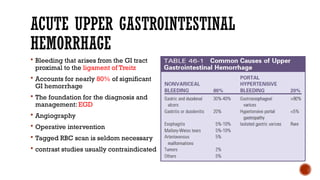

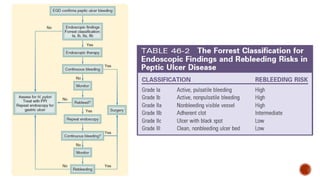

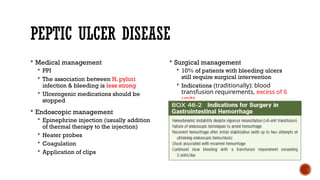

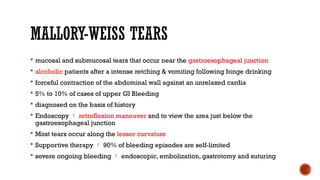

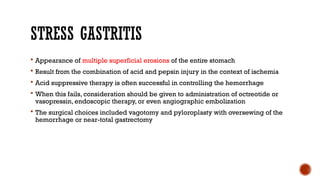

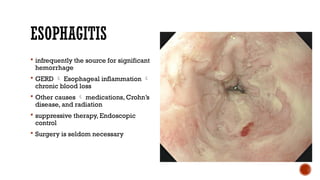

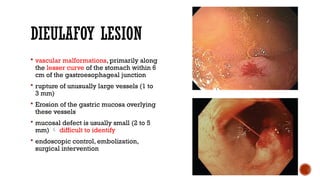

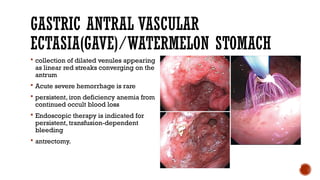

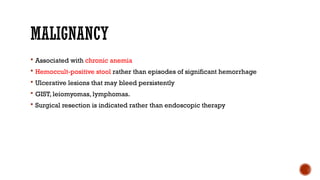

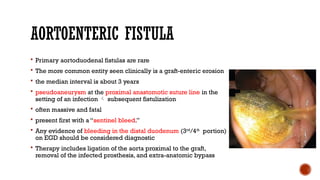

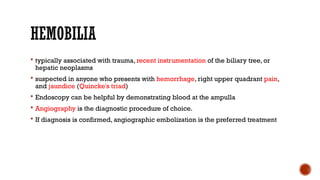

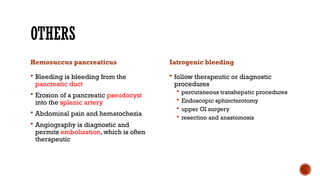

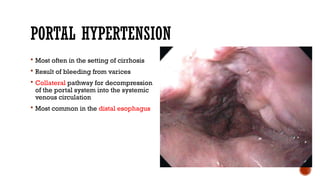

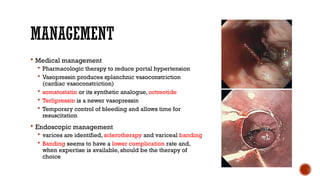

The presentatin is about Upper Gastro Intestinal Bleeding, its causes, approach to the patients with GI Haemorrhage, initial assessment, resuscitation, history and physical examination, localisation, specific causes of GI Haemorrhage, investigations and managements.