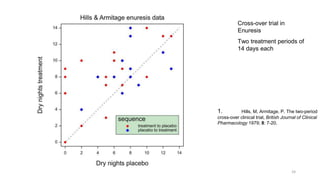

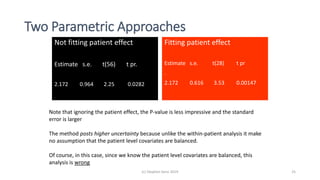

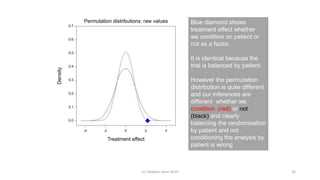

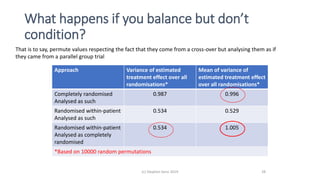

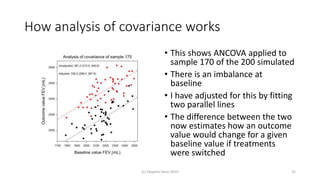

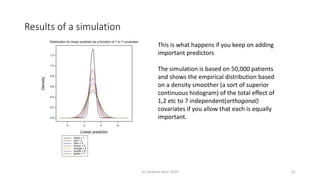

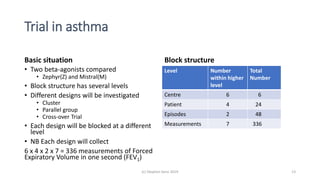

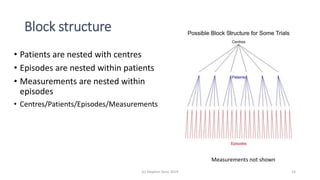

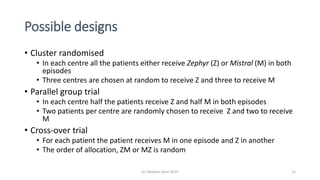

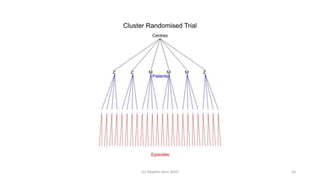

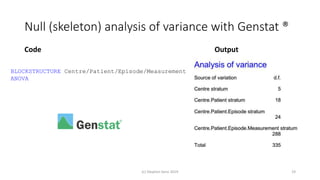

Randomisation balances both known and unknown factors that influence outcomes between treatment groups on average. Conditioning the analysis on available baseline covariates further reduces uncertainty by accounting for imbalances. While there are many potential covariates, their combined influence is bounded; randomisation thus remains important for accounting for unknown factors. Correct analysis requires matching the randomisation design to the analysis to make valid statistical inferences.

![Full (skeleton) analysis of variance with Genstat ®

Additional Code Output

(c) Stephen Senn 2019 20

TREATMENTSTRUCTURE Design[]

ANOVA

(Here Design[] is a pointer with values corresponding

to each of the three designs.)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/understandingrandomisationv2-190804160006/85/Understanding-randomisation-20-320.jpg)