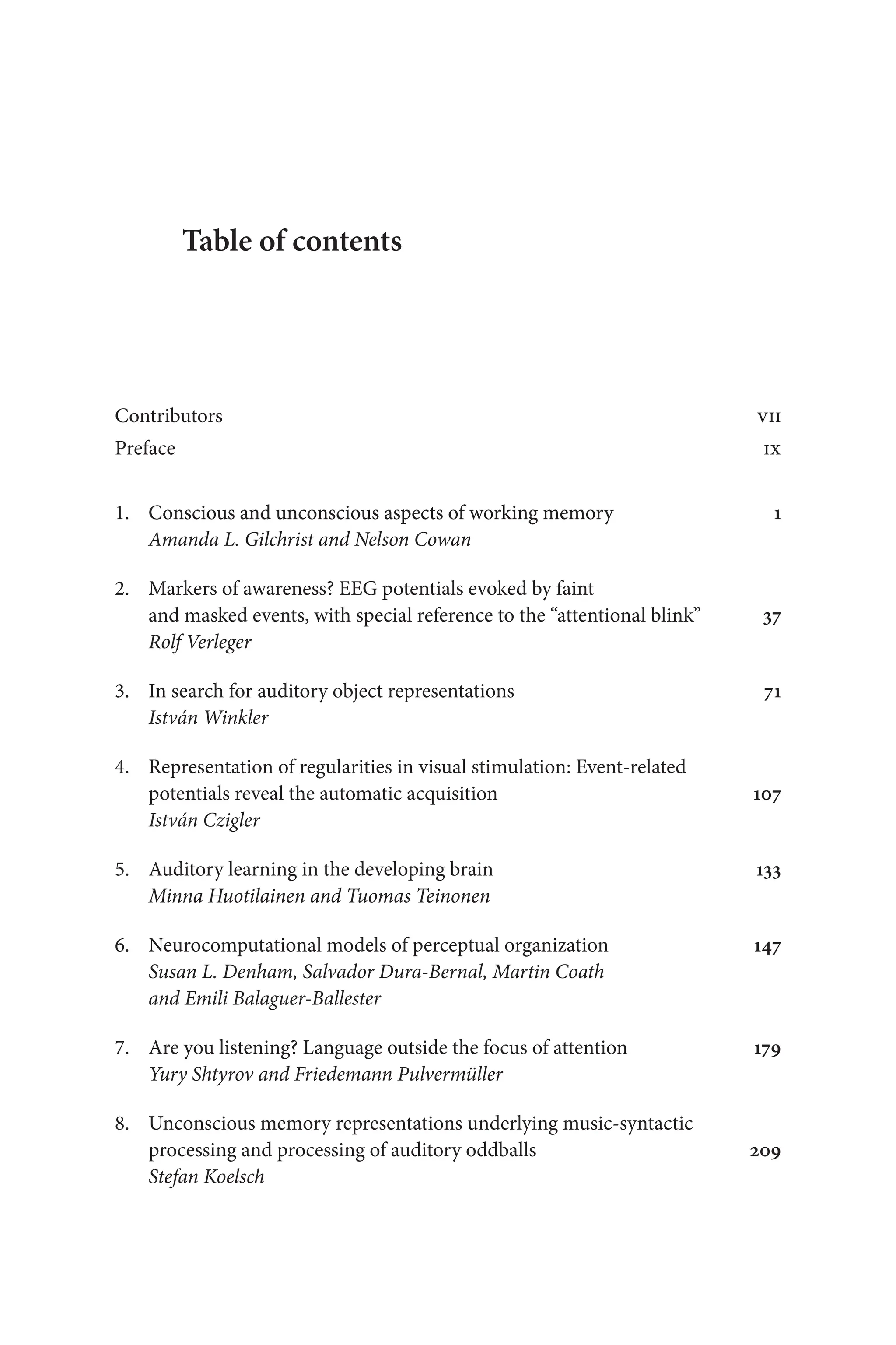

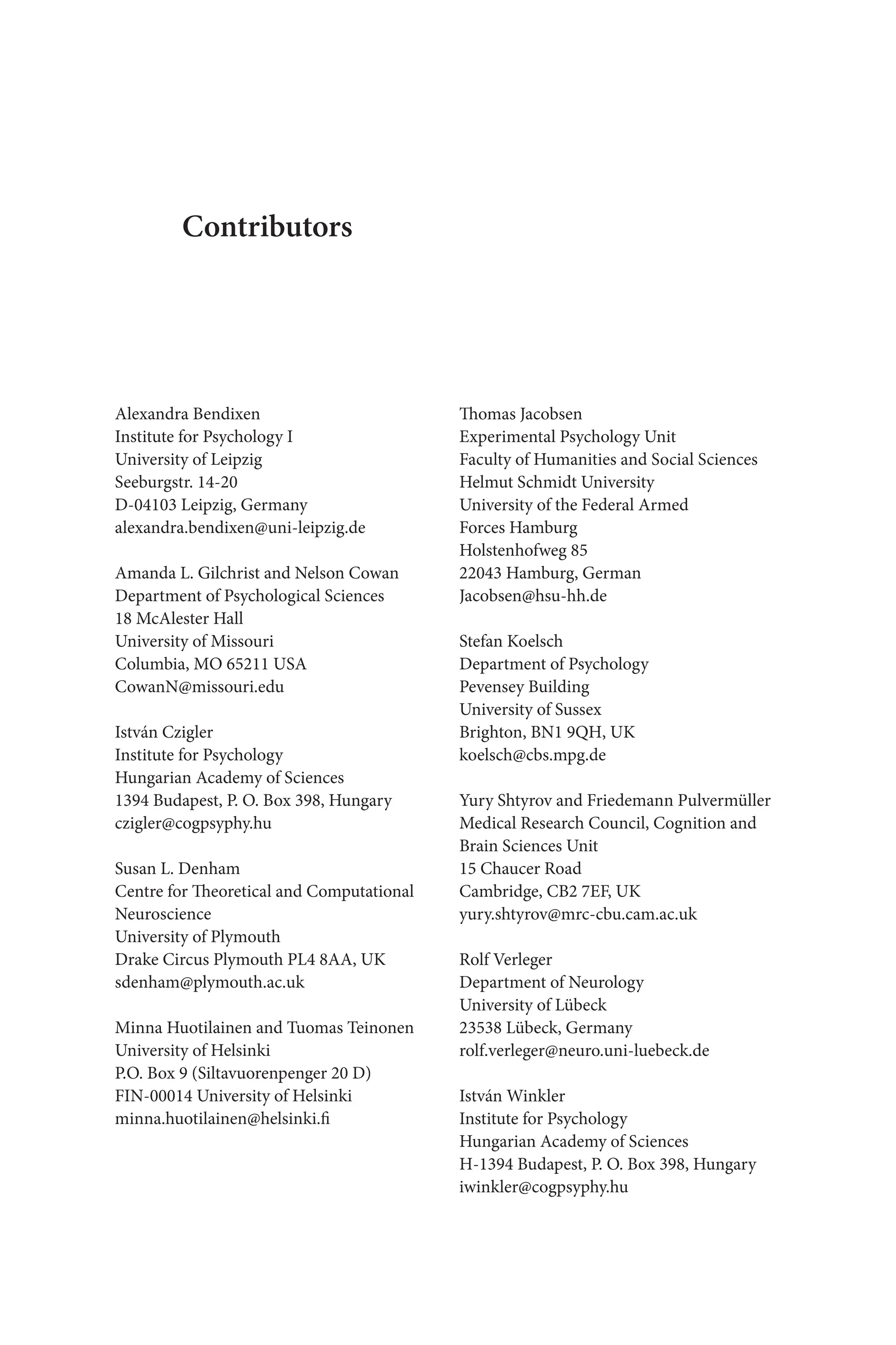

Unconscious Memory Representations in Perception Processes and mechanisms in the brain 1st Edition Istvan Czigler

Unconscious Memory Representations in Perception Processes and mechanisms in the brain 1st Edition Istvan Czigler

Unconscious Memory Representations in Perception Processes and mechanisms in the brain 1st Edition Istvan Czigler