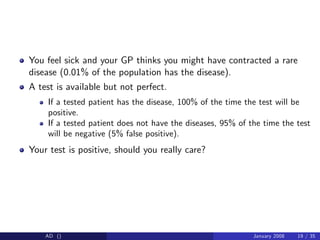

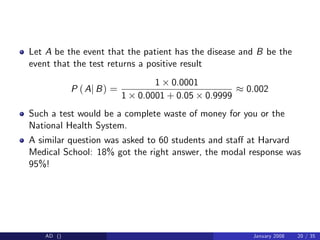

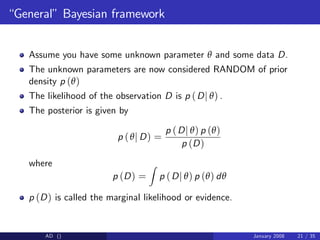

This document outlines the basics of probability and statistics as related to machine learning, covering concepts such as sample spaces, events, random variables, and probability distributions. It discusses important statistical principles including the Central Limit Theorem, Bayes' Rule, and maximum likelihood estimation, emphasizing both Bayesian and frequentist interpretations of probability. Various examples illustrate the application of these concepts in real-world scenarios, highlighting the significance of correct probabilistic reasoning.

![Probability for continuous variables

We typically do not work with probability distributions but with

densities.

We have

P (X 2 A) =

Z

A

pX (x) dx.

so Z

Ω

pX (x) dx = 1

We have

P (X 2 [x, x + δx]) pX (x) δx

Warning: A density evaluated at a point can be bigger than 1.

AD () January 2008 6 / 35](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lec2cs540handouts-230226033408-7ae30996/85/lec2_CS540_handouts-pdf-6-320.jpg)

![Law of large numbers

Assume you have Xi

i.i.d.

pX ( ) then

lim

n!∞

1

n

n

∑

i=1

ϕ (Xi ) = E [ϕ (X)] =

Z

ϕ (x) pX (x) dx

The result is still valid for weakly dependent random variables.

AD () January 2008 10 / 35](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lec2cs540handouts-230226033408-7ae30996/85/lec2_CS540_handouts-pdf-10-320.jpg)

![Central limit theorem

Let Xi

i.i.d.

pX ( ) such that E [Xi ] = µ and V (Xi ) = σ2 then

p

n

1

n

n

∑

i=1

Xi µ

!

D

! N 0, σ2

.

This result is (too) often used to justify the Gaussian assumption

AD () January 2008 11 / 35](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lec2cs540handouts-230226033408-7ae30996/85/lec2_CS540_handouts-pdf-11-320.jpg)

![Bayesian inference involves passing from a prior p (θ) to a posterior

p (θj D) .We might expect that because the posterior incorporates the

information from the data, it will be less variable than the prior.

We have the following identities

E [θ] = E [E [θj D]] ,

V [θ] = E [V [θj D]] + V [E [θj D]] .

It means that, on average (over the realizations of the data X) we

expect the conditional expectation E [θj D] to be equal to E [θ] and

the posterior variance to be on average smaller than the prior variance

by an amount that depend on the variations in posterior means over

the distribution of possible data.

AD () January 2008 23 / 35](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lec2cs540handouts-230226033408-7ae30996/85/lec2_CS540_handouts-pdf-23-320.jpg)

![If (θ, X) are two scalar random variables then we have

V [θ] = E [V [θj D]] + V [E [θj D]] .

Proof:

V [θ] = E θ2

E (θ)2

= E E θ2

D (E (E (θj D)))2

= E E θ2

D E (E (θj D))2

+E (E (θj D))2

(E (E (θj D)))2

= E (V (θj X)) + V (E (θj X)) .

Such results appear attractive but one should be careful. Here there is

an underlying assumption that the observations are indeed distributed

according to p (D) .

AD () January 2008 24 / 35](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lec2cs540handouts-230226033408-7ae30996/85/lec2_CS540_handouts-pdf-24-320.jpg)

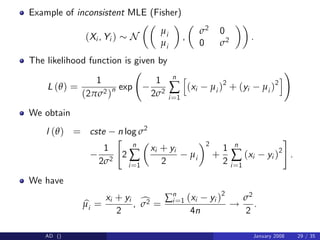

![MLE for 1D Gaussian

Consider Xi

i.i.d.

N µ, σ2 then

p Dj µ, σ2

=

N

∏

i=1

N xi ; µ, σ2

so

l (θ) =

N

2

log (2π)

N

2

log σ2 1

2σ2

N

∑

i=1

(xi µ)2

Setting

∂l(θ)

∂µ = ∂l(θ)

∂σ2 = 0 yields

b

µML =

1

N

N

∑

i=1

xi ,

c

σ2

ML =

1

N

N

∑

i=1

(xi b

µML)2

.

We have E [b

µML] = µ and E

h

c

σ2

ML

i

= N

N 1 σ2.

AD () January 2008 27 / 35](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lec2cs540handouts-230226033408-7ae30996/85/lec2_CS540_handouts-pdf-27-320.jpg)

![Asymptotic Normality

Assuming b

θN is a consistent estimate of θ , we have under regularity

assumptions

p

N b

θN θ ) N 0, [I (θ )] 1

where

[I (θ)]k,l = E

∂2 log p (xj θ)

∂θk ∂θl

We can estimate I (θ ) through

[I (θ )]k,l =

1

N

N

∑

i=1

∂2 log p (Xi j θ)

∂θk ∂θl b

θN

AD () January 2008 32 / 35](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lec2cs540handouts-230226033408-7ae30996/85/lec2_CS540_handouts-pdf-32-320.jpg)

![Frequentist con…dence intervals

The MLE being approximately Gaussian, it is possible to de…ne

(approximate) con…dence intervals.

However be careful, “θ has a 95% con…dence interval of [a, b]” does

NOT mean that P (θ 2 [a, b]j D) = 0.95.

It means

PD0 P( jD) θ 2 a D0

, b D0

= 0.95

i.e., if we were to repeat the experiment, then 95% of the time, the

true parameter would be in that interval. This does not mean that we

believe it is in that interval given the actual data D we have observed.

AD () January 2008 34 / 35](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lec2cs540handouts-230226033408-7ae30996/85/lec2_CS540_handouts-pdf-34-320.jpg)