This document outlines the requirements for a graded discussion forum in an education course. Students must make an initial post by Day 3 sharing the key details of an action research study they reviewed. They then must respond to at least two peers by Day 7. Initial posts should include the purpose, research questions, outcomes, modifications for future studies, and importance of the study. Responses should take the role of a teacher listening to a presentation, asking questions and offering alternative viewpoints. Students will also reflect on redesigning a previous assignment and how it promotes learning skills and ongoing evaluation.

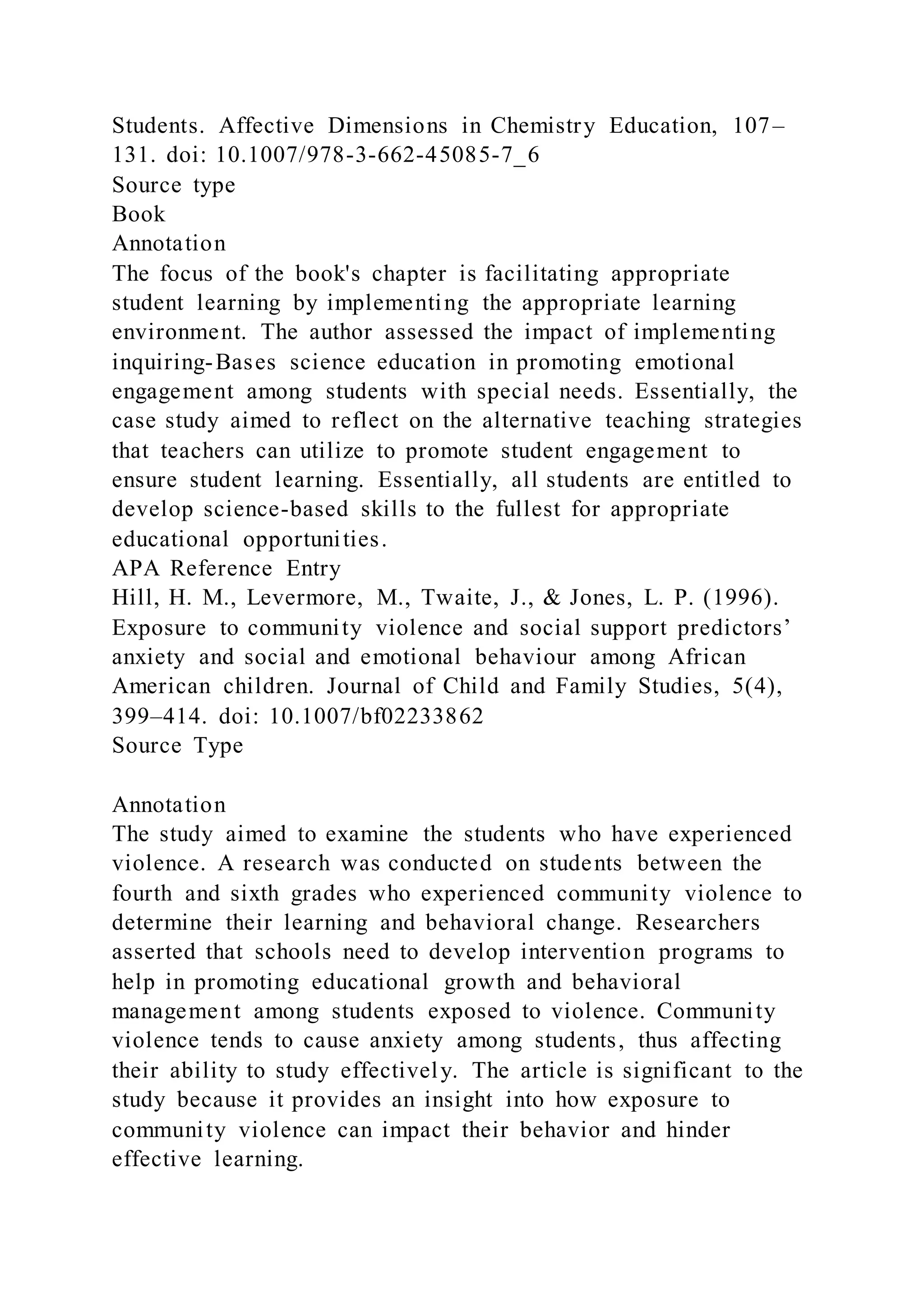

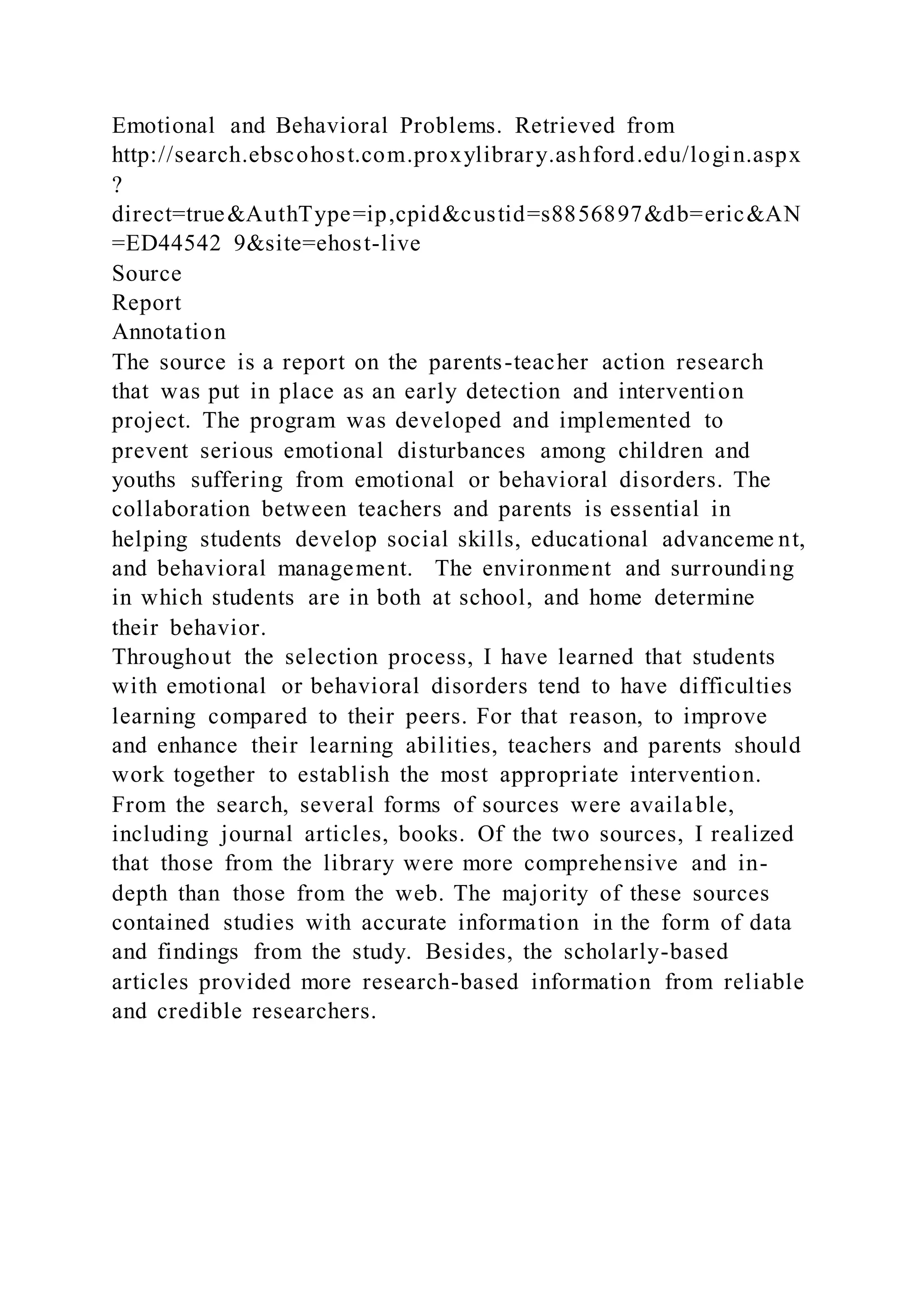

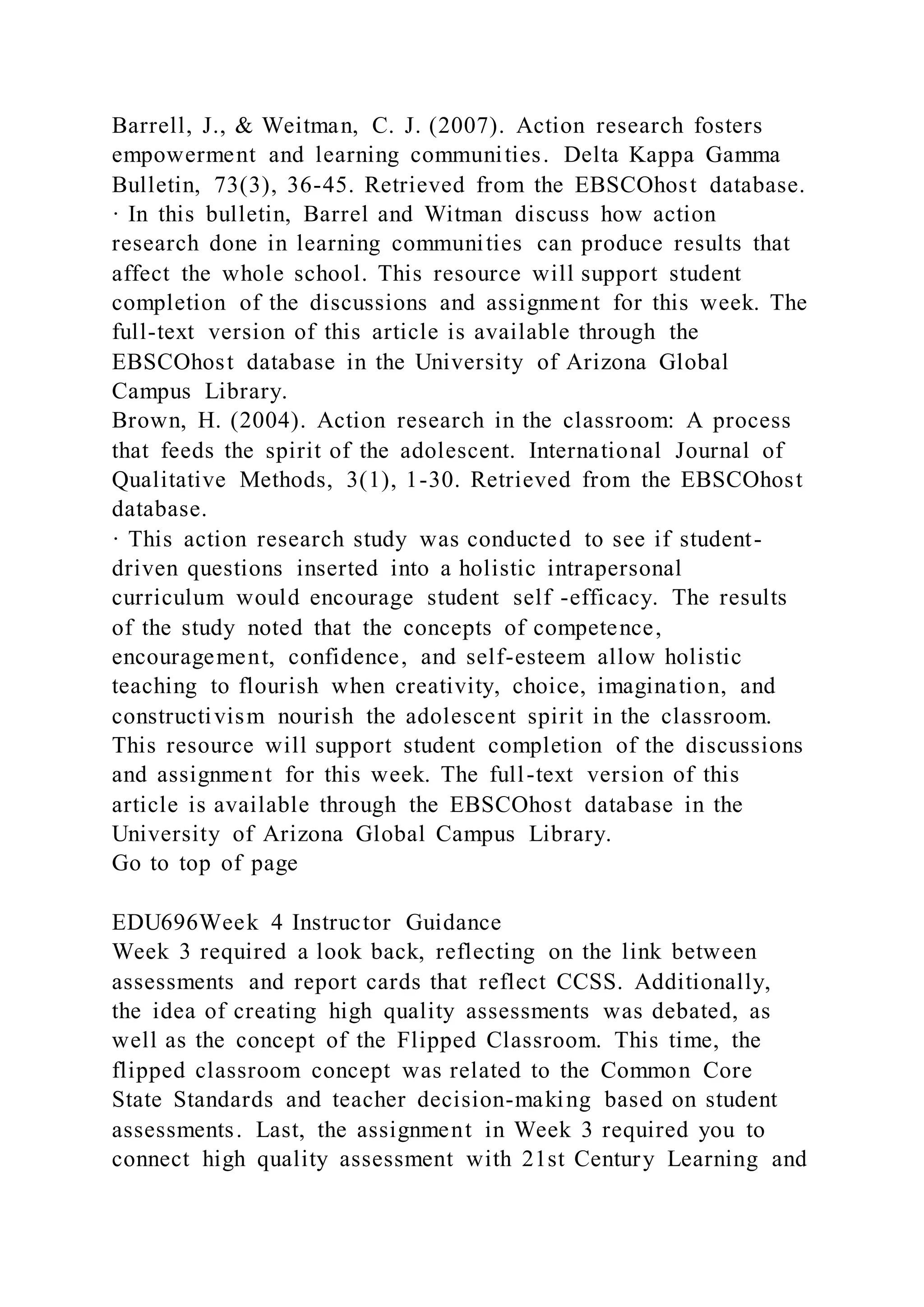

![arch reflect the diverse ways in which the same set of activities

may be described, although the processes they delineate are sim

ilar. There are, after all, many ways of cutting a cake.

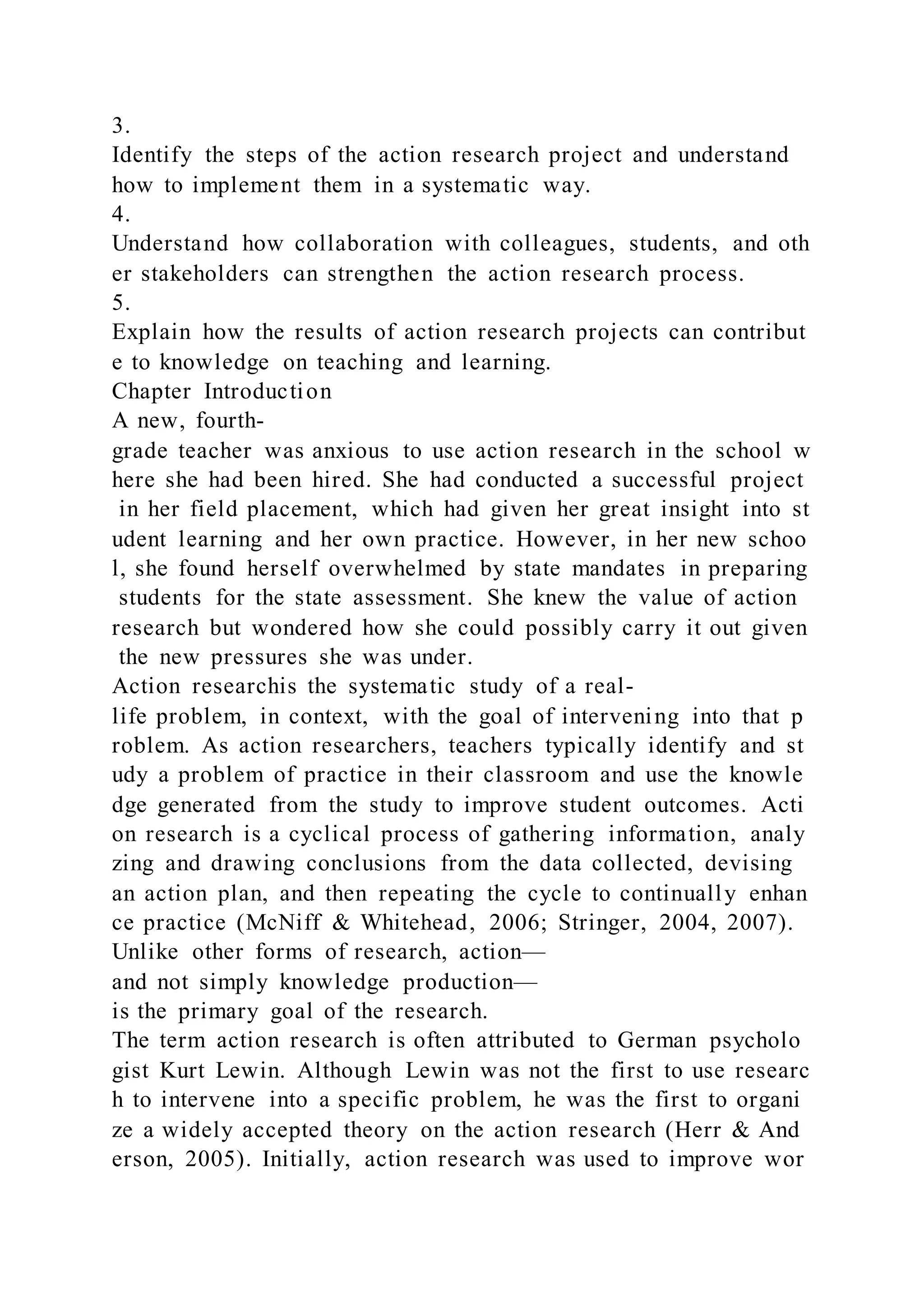

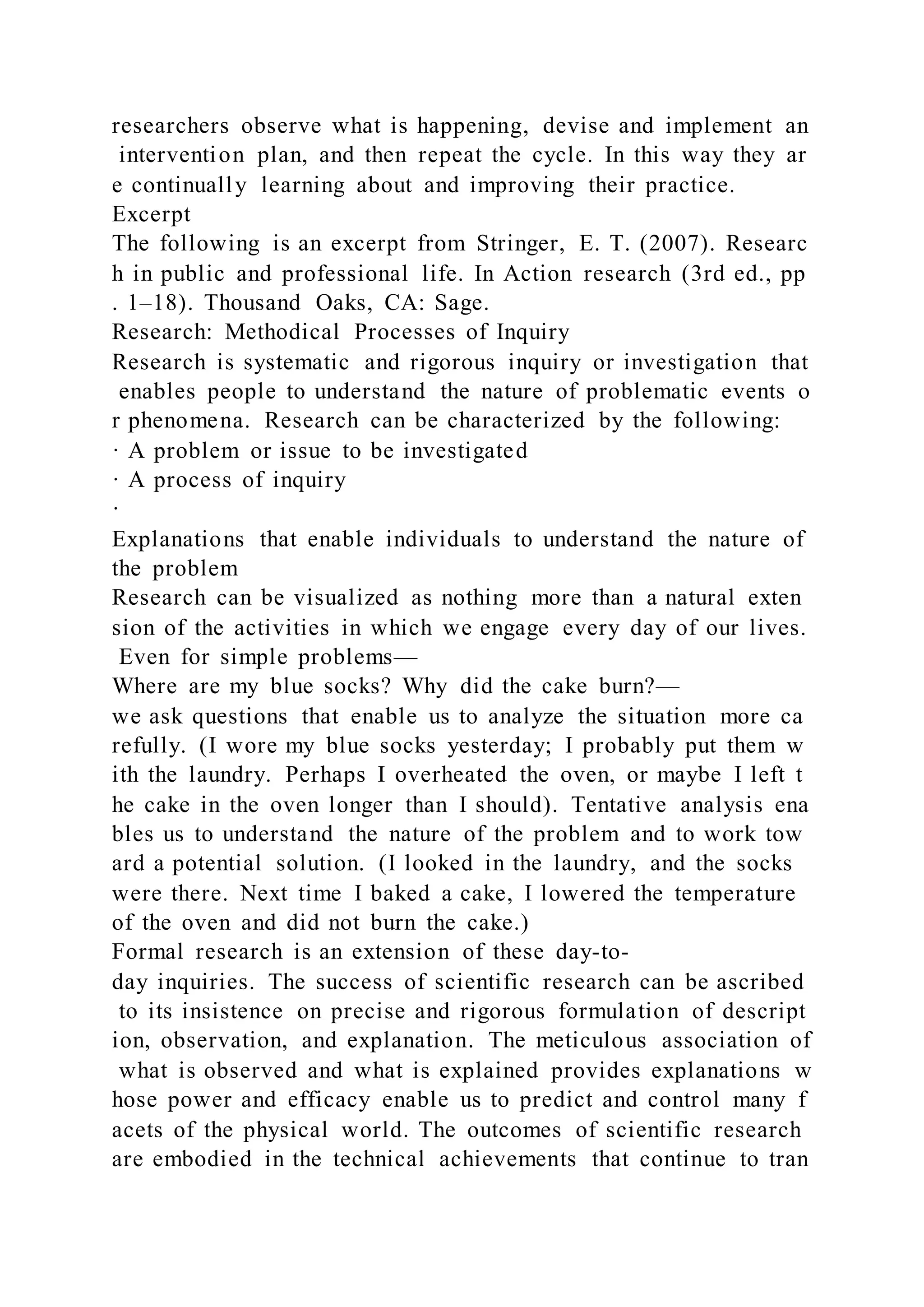

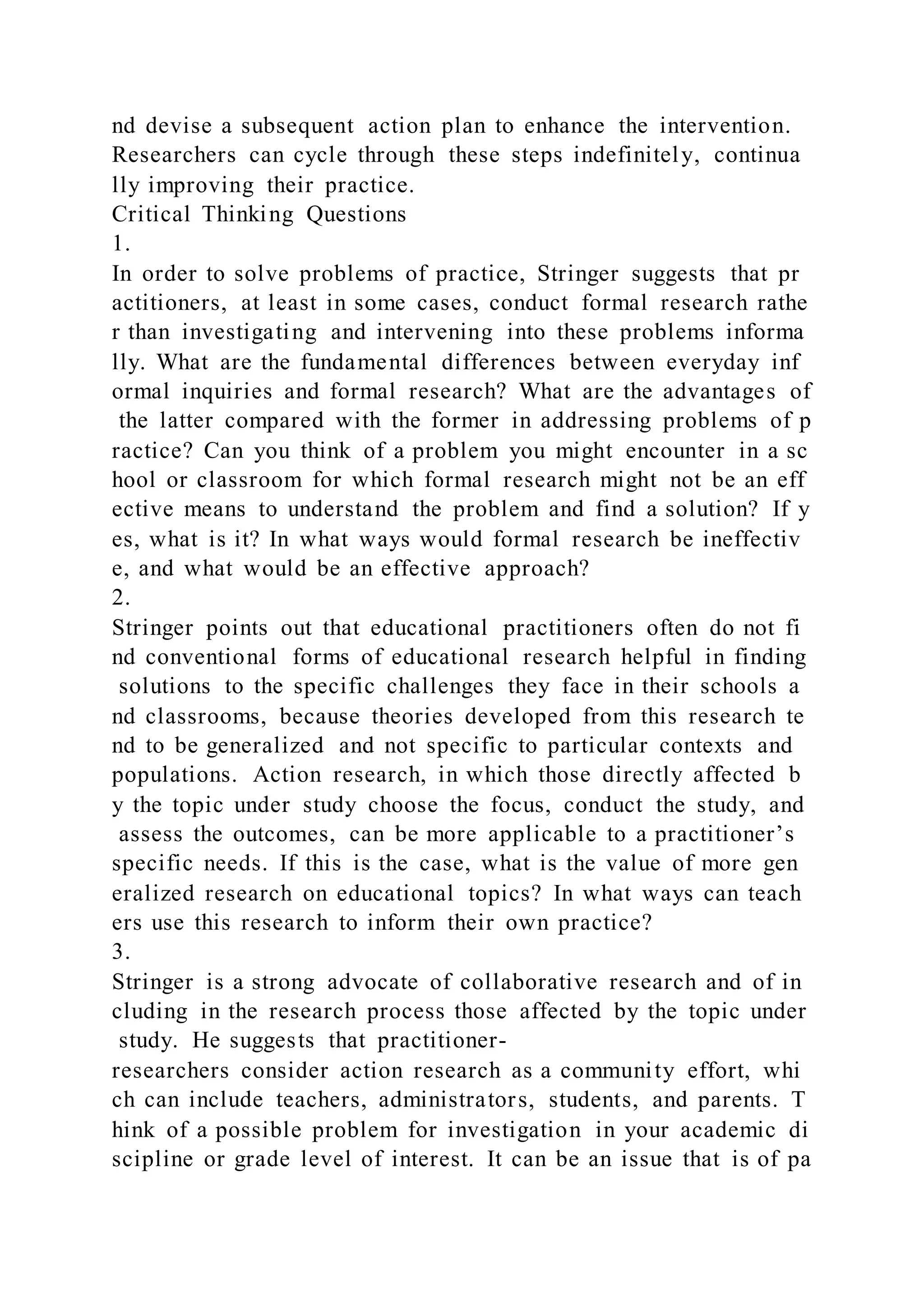

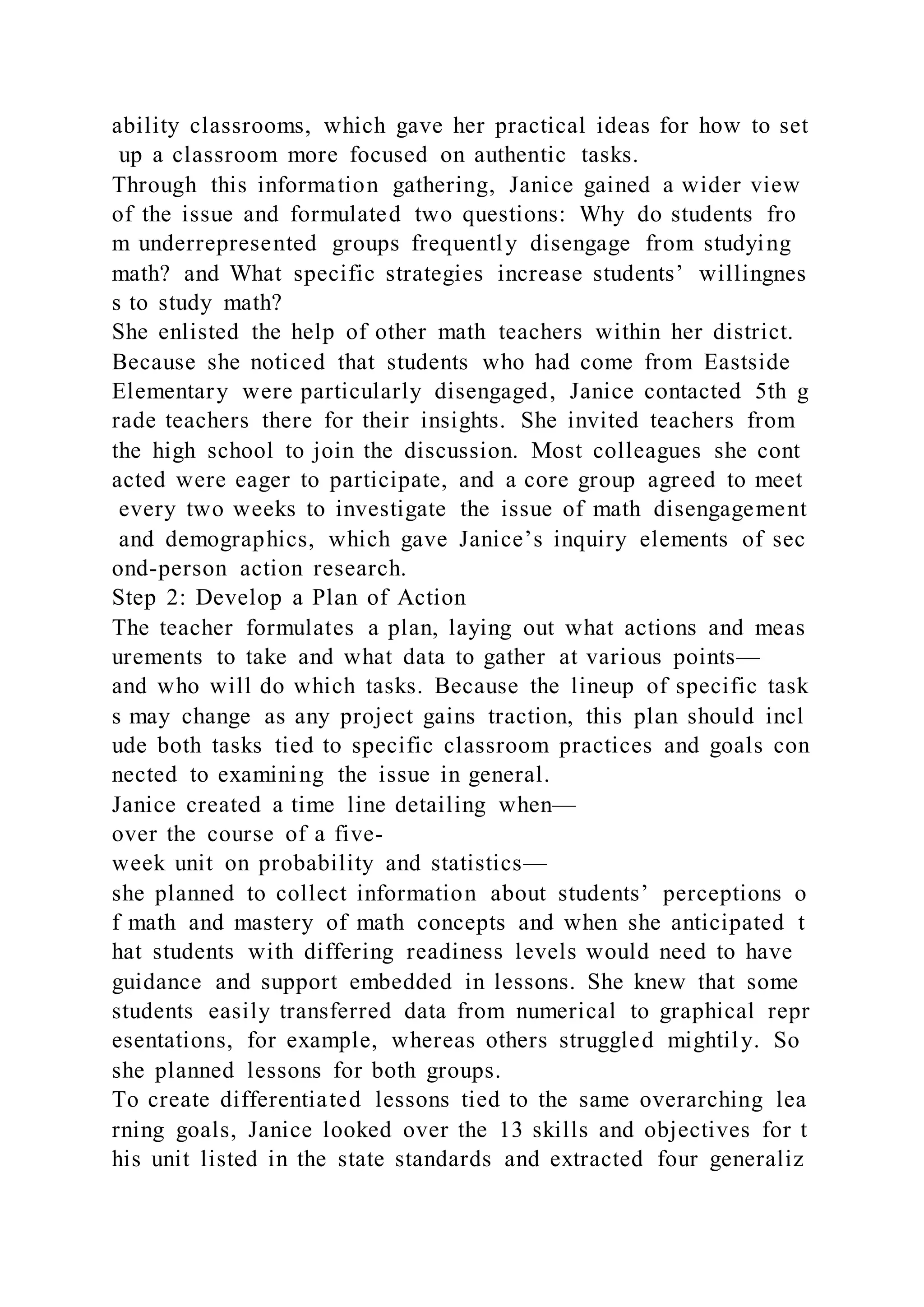

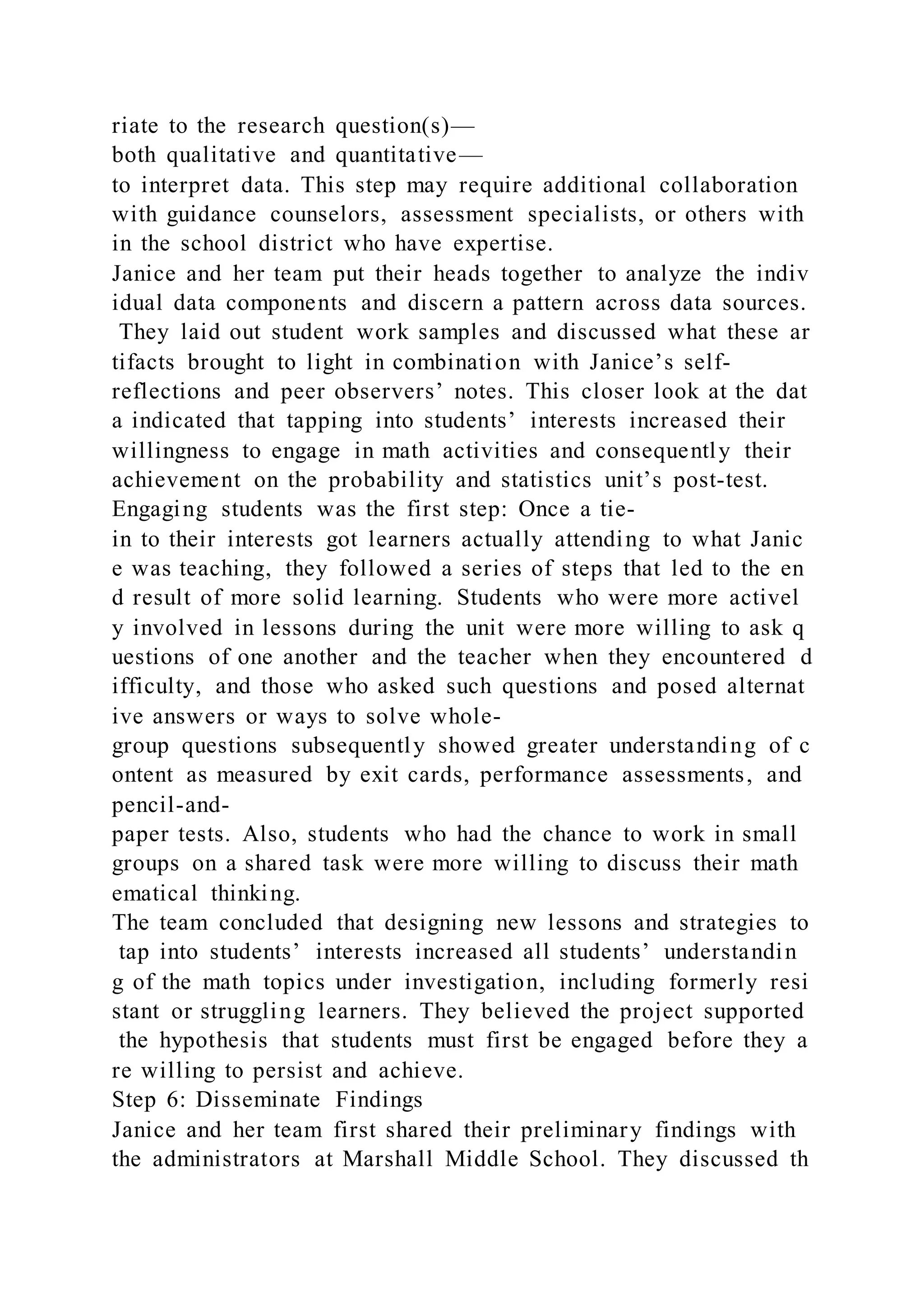

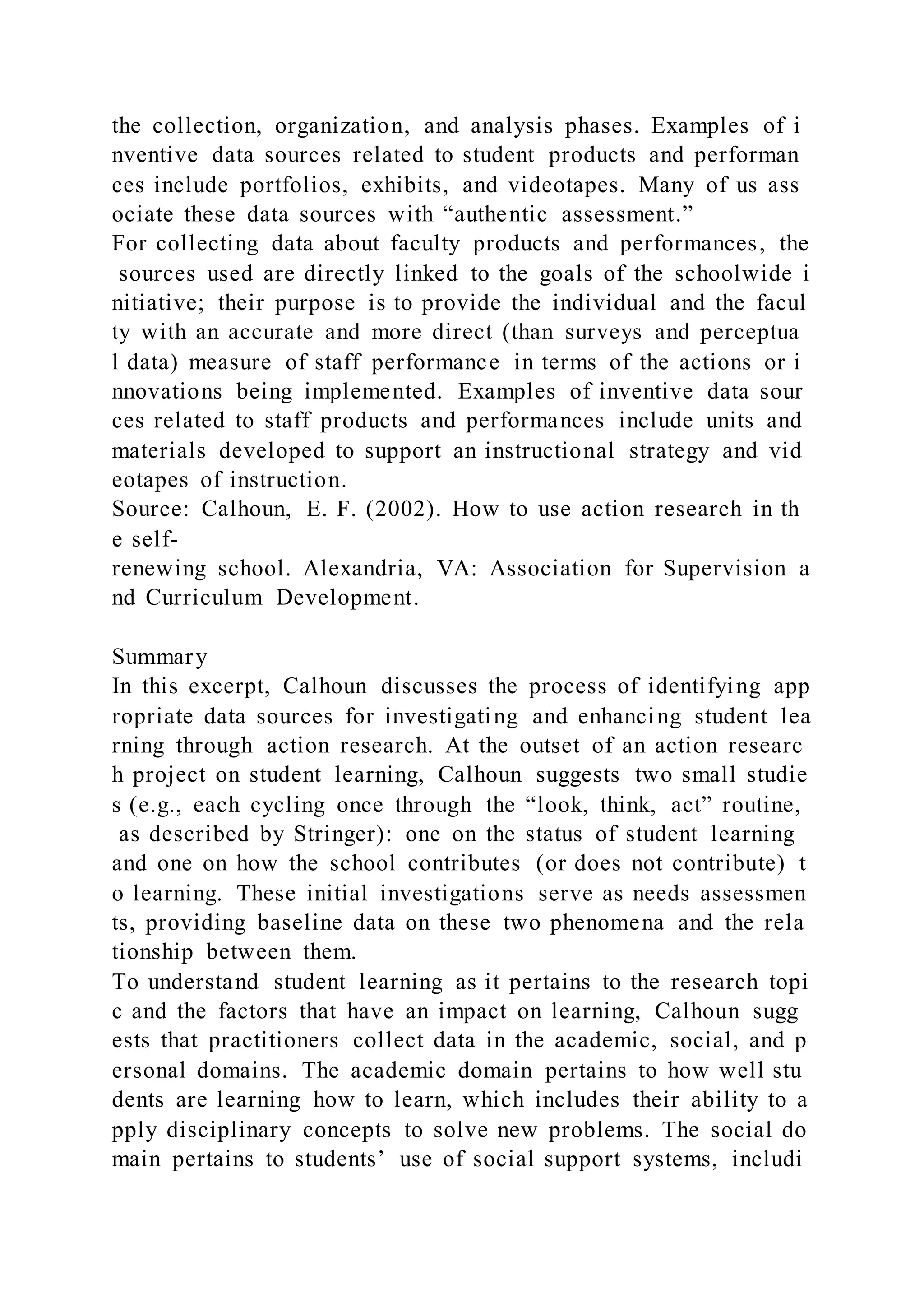

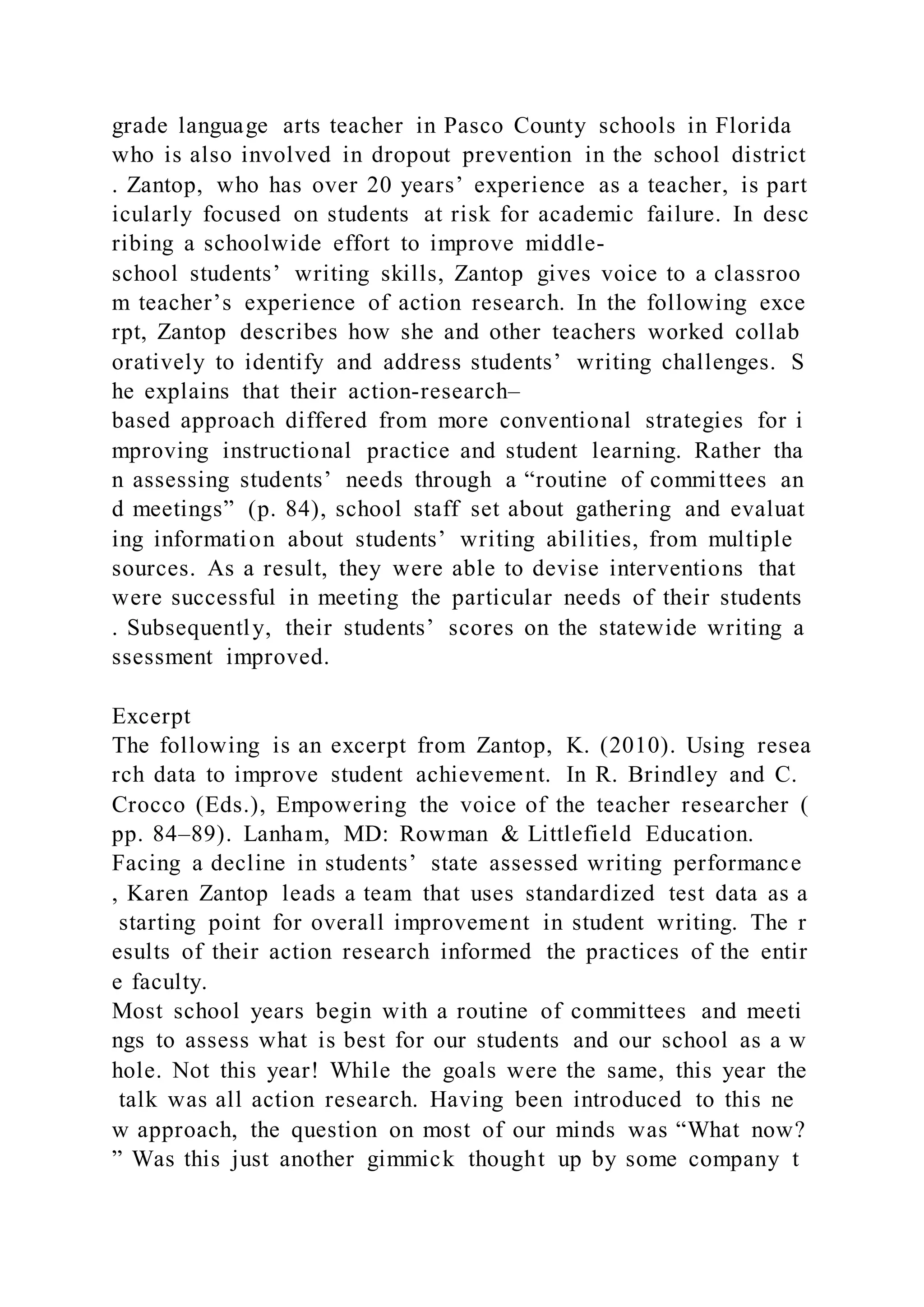

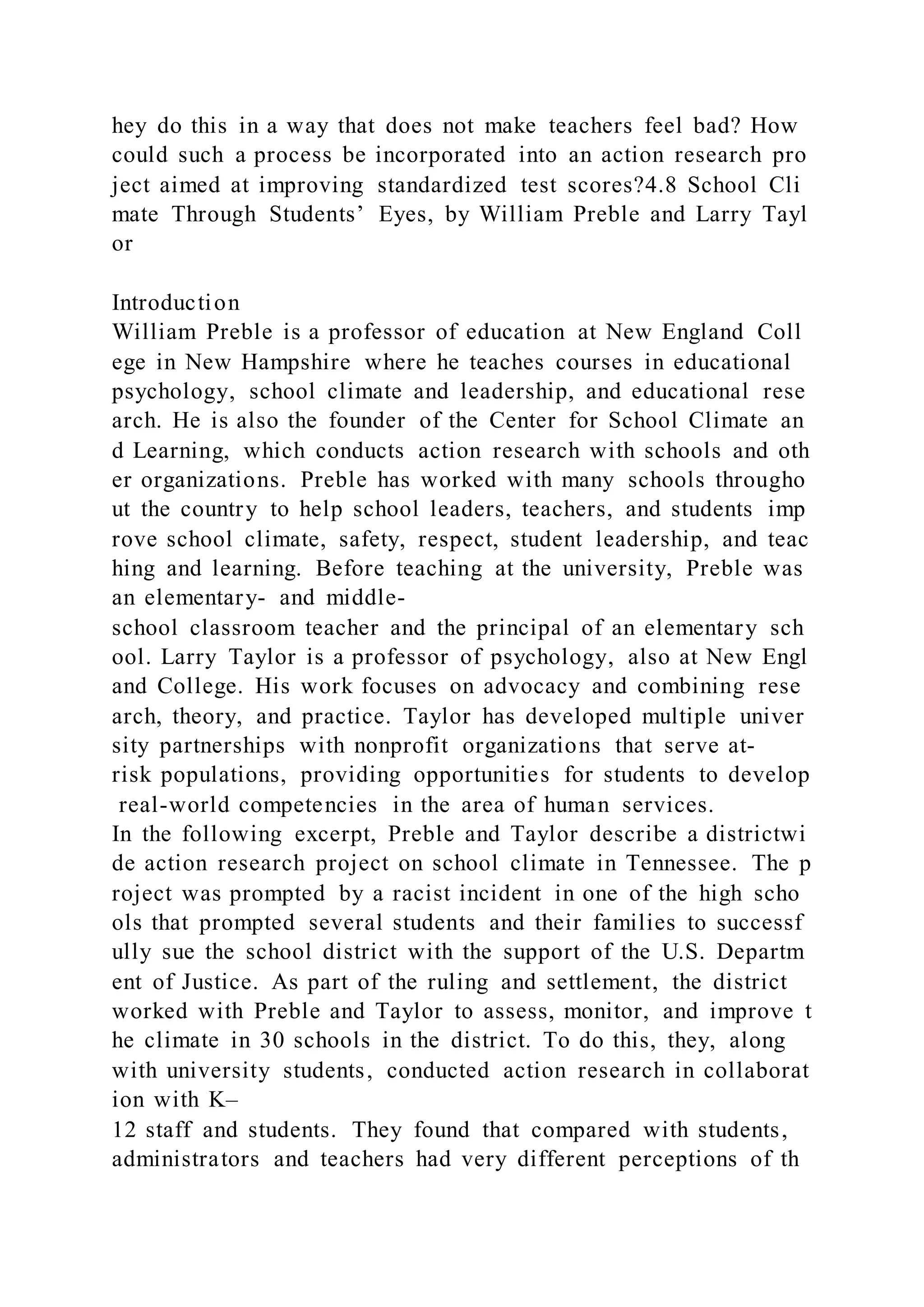

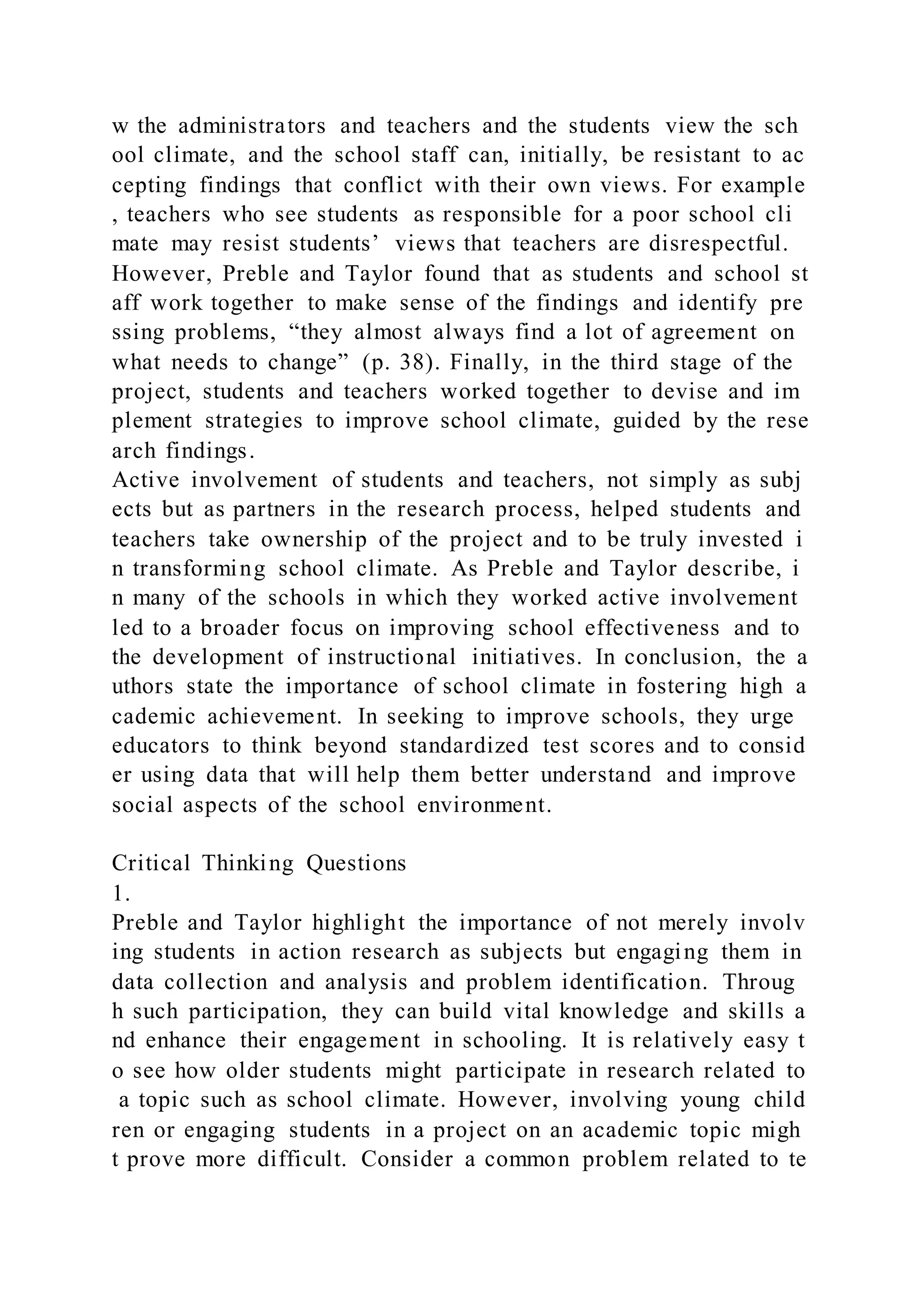

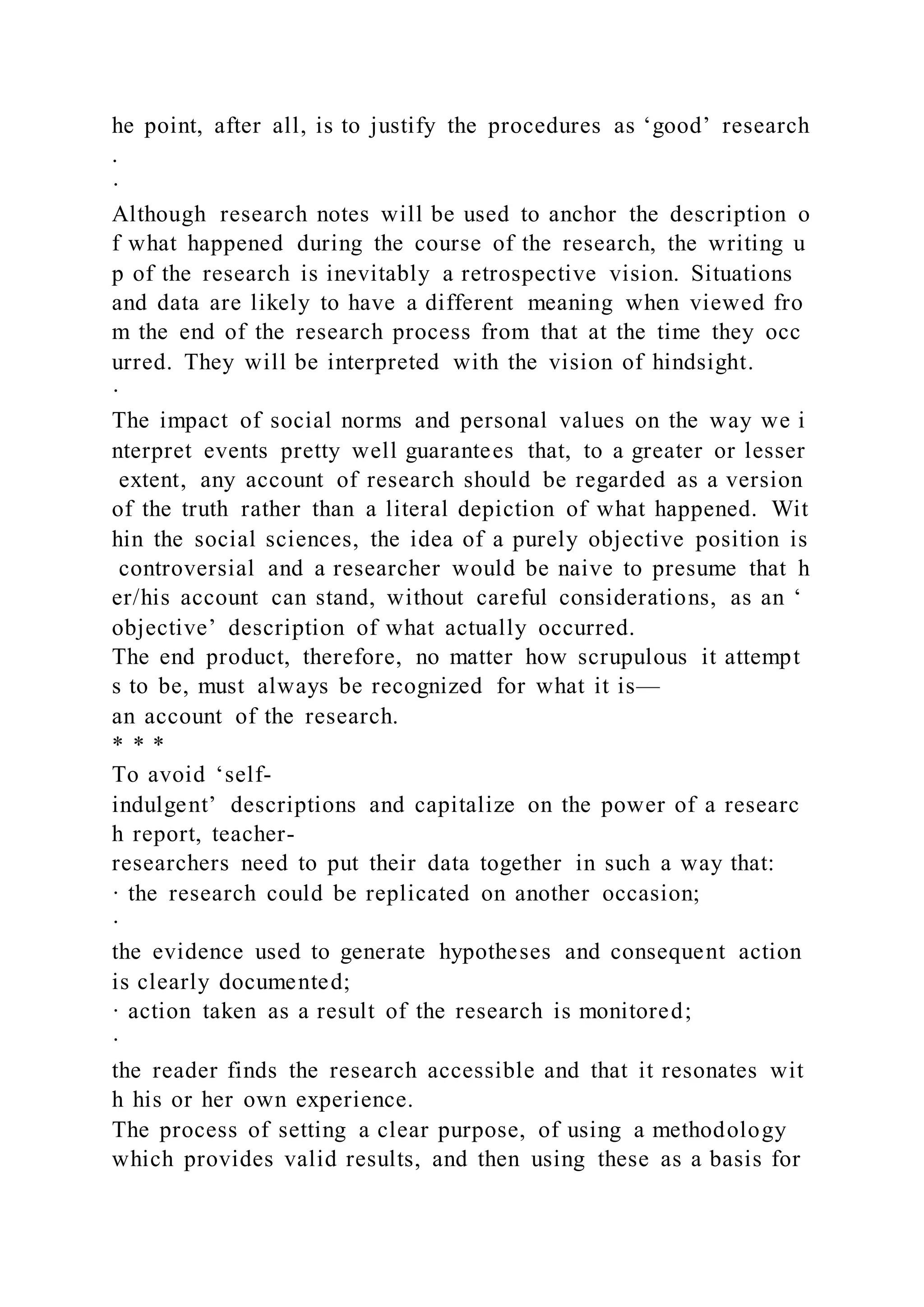

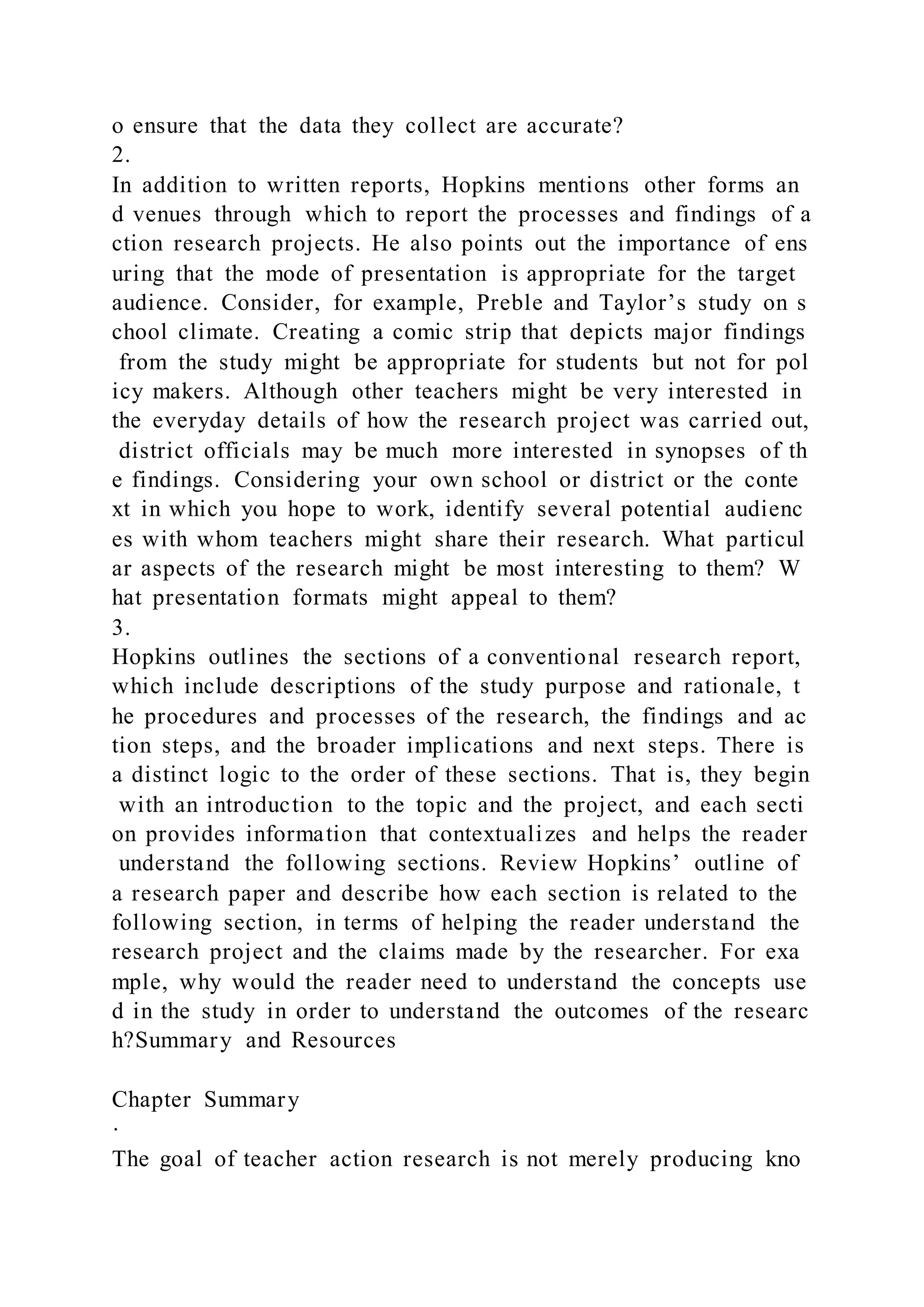

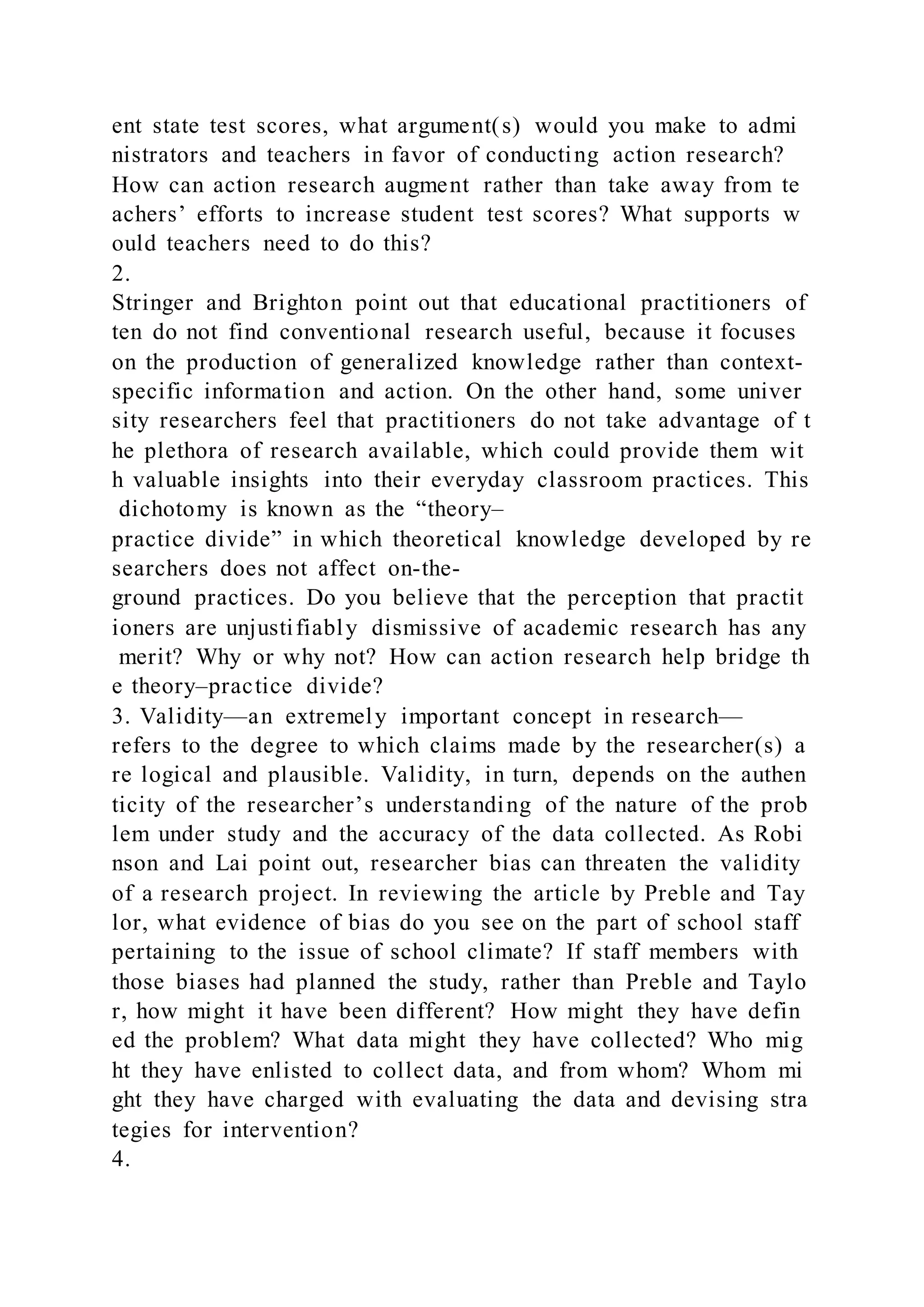

Although the “look, think, act” routine is presented in a linear f

ormat throughout this book, is should be read as a continually re

cycling set of activities (see Figure 4.1). As participants work t

hrough each of the major stages, they will explore the details of

their activities through a constant process of observation, reflec

tion, and action. At the completion of each set of activities, they

will review (look again), reflect (reanalyze), and re-

act (modify their actions). As experience will show, action resea

rch is not a neat, orderly activity that allows participants to proc

eed step-by-

step to the end of the process. People will find themselves work

ing backward through the routines, repeating processes, revising

procedures, rethinking interpretations, leapfrogging steps or sta

ges, and sometimes making radical changes in direction.

Figure 4.1: Action research interacting spiral

In practice, therefore, action research can be a complex process.

The routines presented in this book, however, can be visualized

as a road map that provides guidance to those who follow this l

ess traveled way. Although there may be many routes to a destin

ation, and although destinations may change, travelers on the jo

urney will be able to maintain a clear idea of their location and

the direction in which they are heading.

The procedures that follow are likely to be ineffective, however,

unless enacted in ways that take into account the social, cultura

l, interactional, and emotional factors that affect all human acti

vity. “The medium is the message!” . . . [T]he implicit values an

d underlying assumptions embedded in action research provide a

set of guiding principles that can facilitate a democratic, partici

patory, liberating, and life-enhancing approach to research.

Source: Stringer, E. T. (2007). Action research, 3rd Edition. Th

ousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Summary](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thisisagradeddiscussion5pointspossibledueoct14week4-211018084924/75/This-is-a-graded-discussion-5-points-possibledue-oct-14-week-4-16-2048.jpg)

![McNiff, J. & Whitehead, J. (2006). All you need to know about

action research. London: Sage.

Morrell, E. (2008). Six summers of YPAR: Learning, action, an

d change in urban education. In J. Cammarota & M. Fine (Eds.),

Revolutionizing education: Youth participatory action research

in motion (pp. 155–184). New York: Routledge.

O’Brien, R. (2001). Um exame da abordagem metodológica da p

esquisa ação [An overview of the methodological approach of a

ction research]. In Roberto Richardson (Ed.), Teoria e prática d

a pesquisa ação [Theory and practice of action research]. João P

essoa, Brazil: Universidade Federal da Paraíba. Available: http:/

/www.web.ca/~robrien/papers/arfinal.html

Preble, B., & Taylor, L. (2008). School climate through students

’ eyes. Educational Leadership, 66(4), 35–40.

Razfar, A. (2011). Action research in urban schools: Empowerm

ent, transformation, and challenges. Teacher Education Quarterl

y, 38(4), 25–44.

Souto-

Manning, M., & Mitchell, C. (2010). The role of action research

in fostering culturally-

responsive practices in a preschool classroom. Early Childhood

Education Journal, 37(4), 269–277.

Spaulding, D. T., & Falco, J. (2013). Action research for school

leaders. Boston, MA: Pearson.

Key Terms

Please click on the key term to reveal the definition.

action plan

action research

baseline data

bias

data

data analysis

data collection

emic

fate-control variables](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thisisagradeddiscussion5pointspossibledueoct14week4-211018084924/75/This-is-a-graded-discussion-5-points-possibledue-oct-14-week-4-119-2048.jpg)

![pesquisa ação (Links to an external site.) [An Overview of the

Methodological Approach of Action Research]. In Roberto

Richardson (Ed.), Teoria e Prática da Pesquisa Ação [Theory

and Practice of Action Research]. João Pessoa, Brazil:

Universidade Federal da Paraíba. (English version). Retrieved

from http://www.web.ca/robrien/papers/arfinal.html#_Toc26184

672 (Links to an external site.)

Additional Resources

Borgman, C. (2007). Scholarship in the digital age: Information,

infrastructure, and the internet. Boston: MIT Press.

Ma, L. (1999, 2010). Knowing and teaching elementary

mathematics. Teachers understanding of fundamental

mathematics in China and the United States. New York:

Routledge

Trochim, G. (2006). Social research methods database (Links to

an external site.). Retrieved from

http://www.socialresearchmethods.net/kb/index.php

Finding Nemo? No, Finding Research

1

Finding Nemo? No, Finding Research

Mary Garcia

EDU 694 Capstone 1: Educational Research

Instructor: Jessica Upshaw

August 16, 2021

APA Reference Entry

Abels, S. (2014). Implementing Inquiry-Based Science

Education to Foster Emotional Engagement of Special-Needs](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thisisagradeddiscussion5pointspossibledueoct14week4-211018084924/75/This-is-a-graded-discussion-5-points-possibledue-oct-14-week-4-125-2048.jpg)