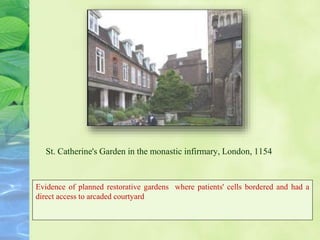

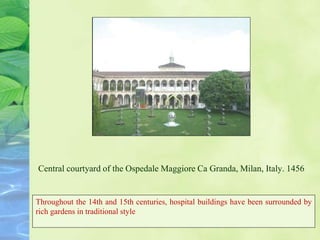

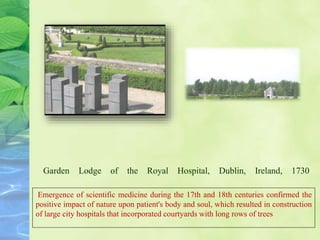

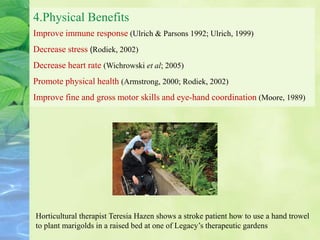

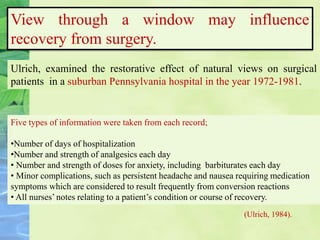

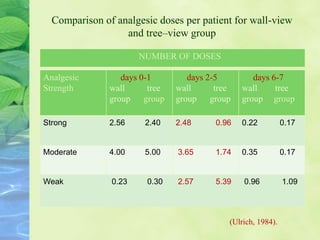

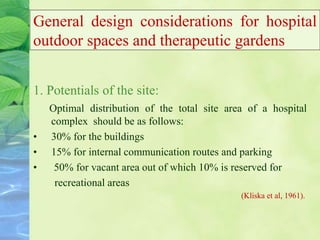

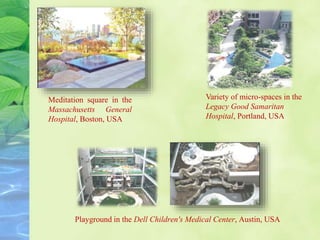

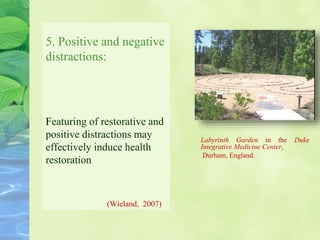

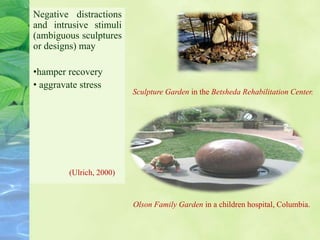

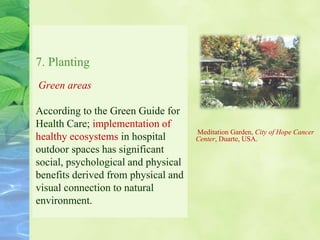

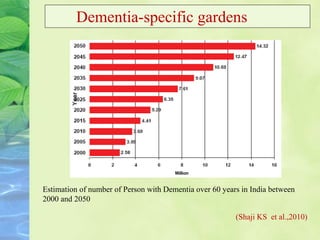

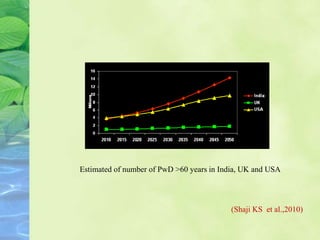

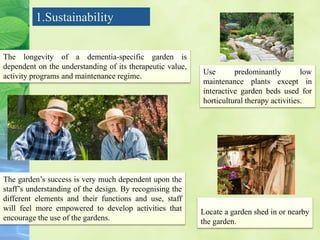

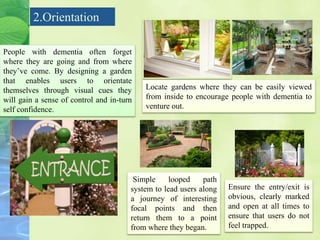

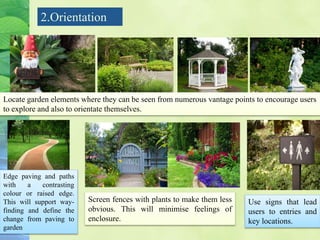

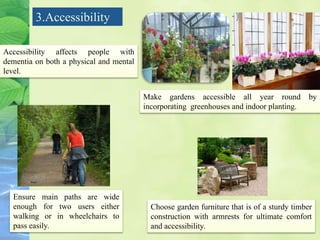

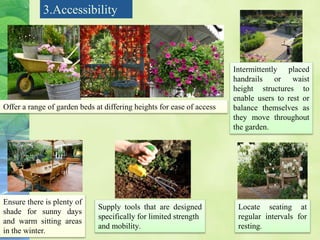

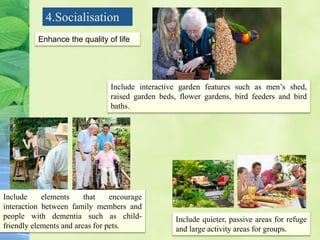

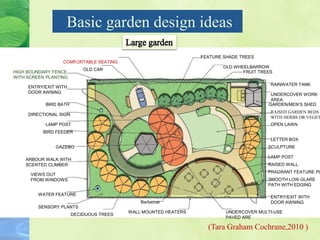

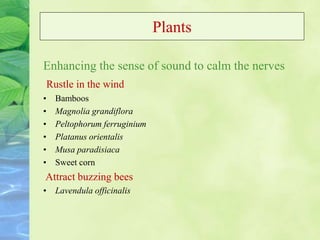

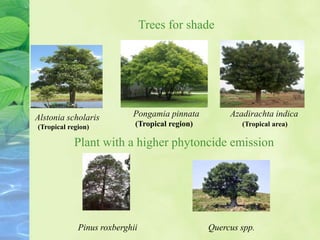

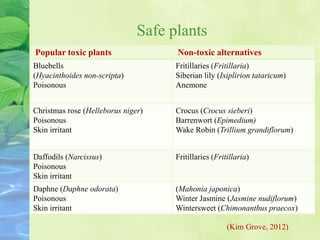

The document discusses the benefits and various types of therapeutic gardens, including healing, therapeutic, horticultural therapy, and restorative gardens, which have gained popularity in treatment programs over the past decade. It highlights historical contexts, cognitive, social, psychological, and physical benefits associated with horticultural therapy, and emphasizes design principles for therapeutic landscapes to cater to diverse user needs. Additionally, it covers specific considerations for dementia-specific gardens, focusing on sustainability, accessibility, and sensory stimulation to enhance the well-being of users.