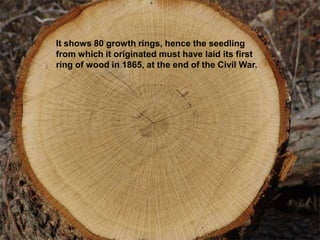

The document contains PowerPoint presentations featuring essays from 'A Sand County Almanac' for public readings at Aldo Leopold Weekend events, with slides that include both text and visual elements. Each presentation is curated by Dave Winefske, and permissions for image use are restricted to these events. Additionally, the text reflects on the growth and history of a particular oak tree, discussing its significance and the environmental context of Wisconsin through various decades.