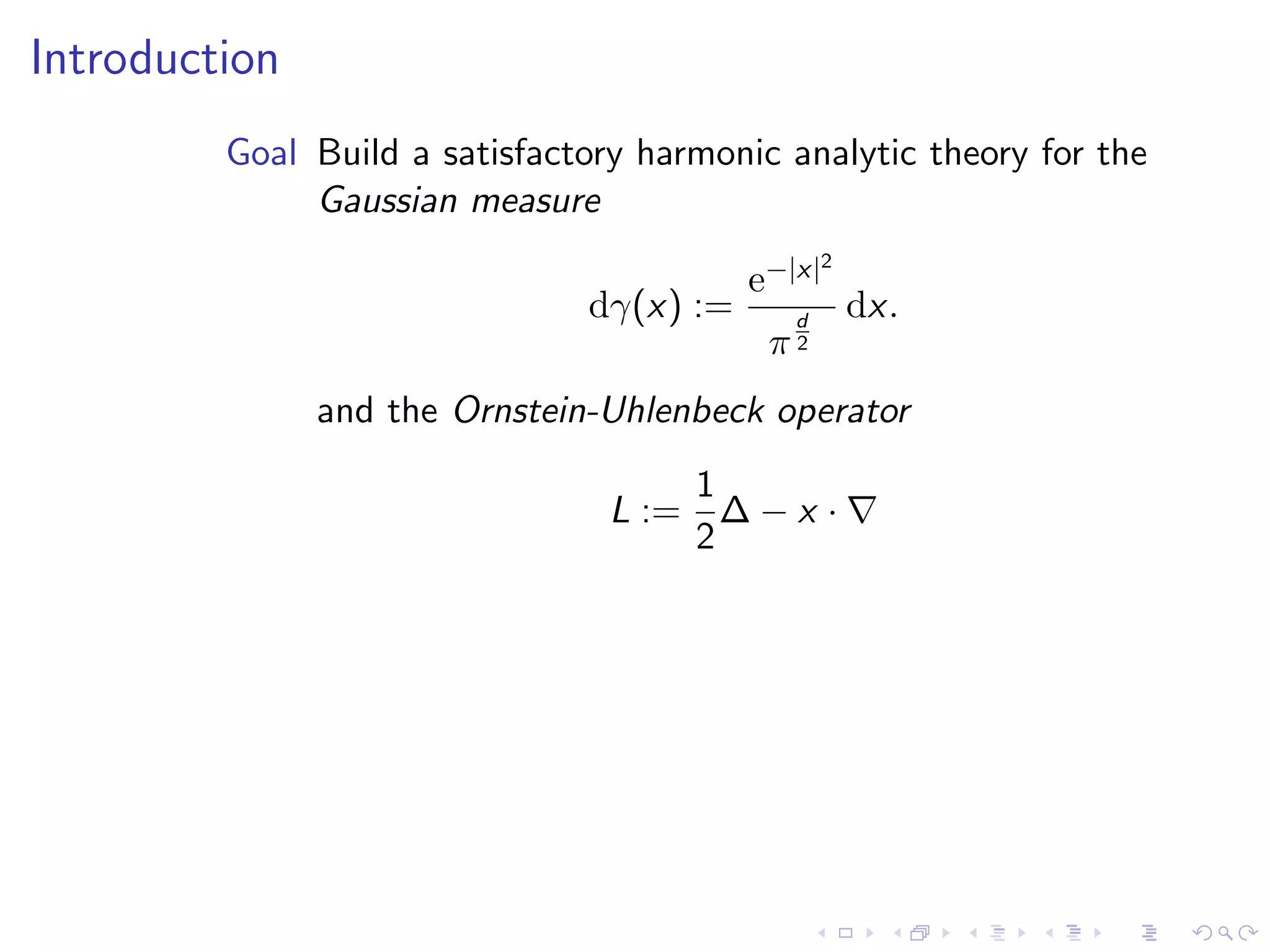

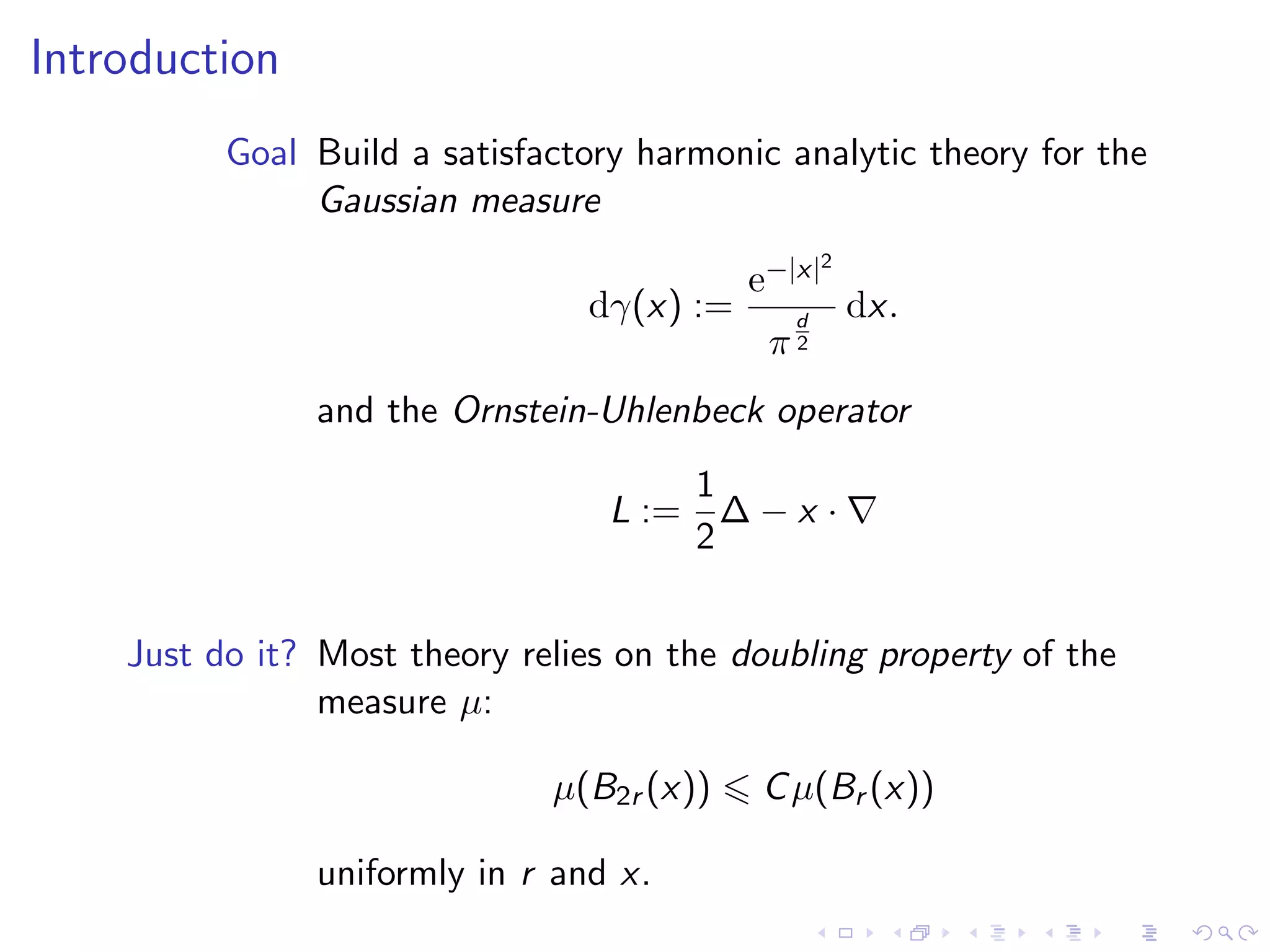

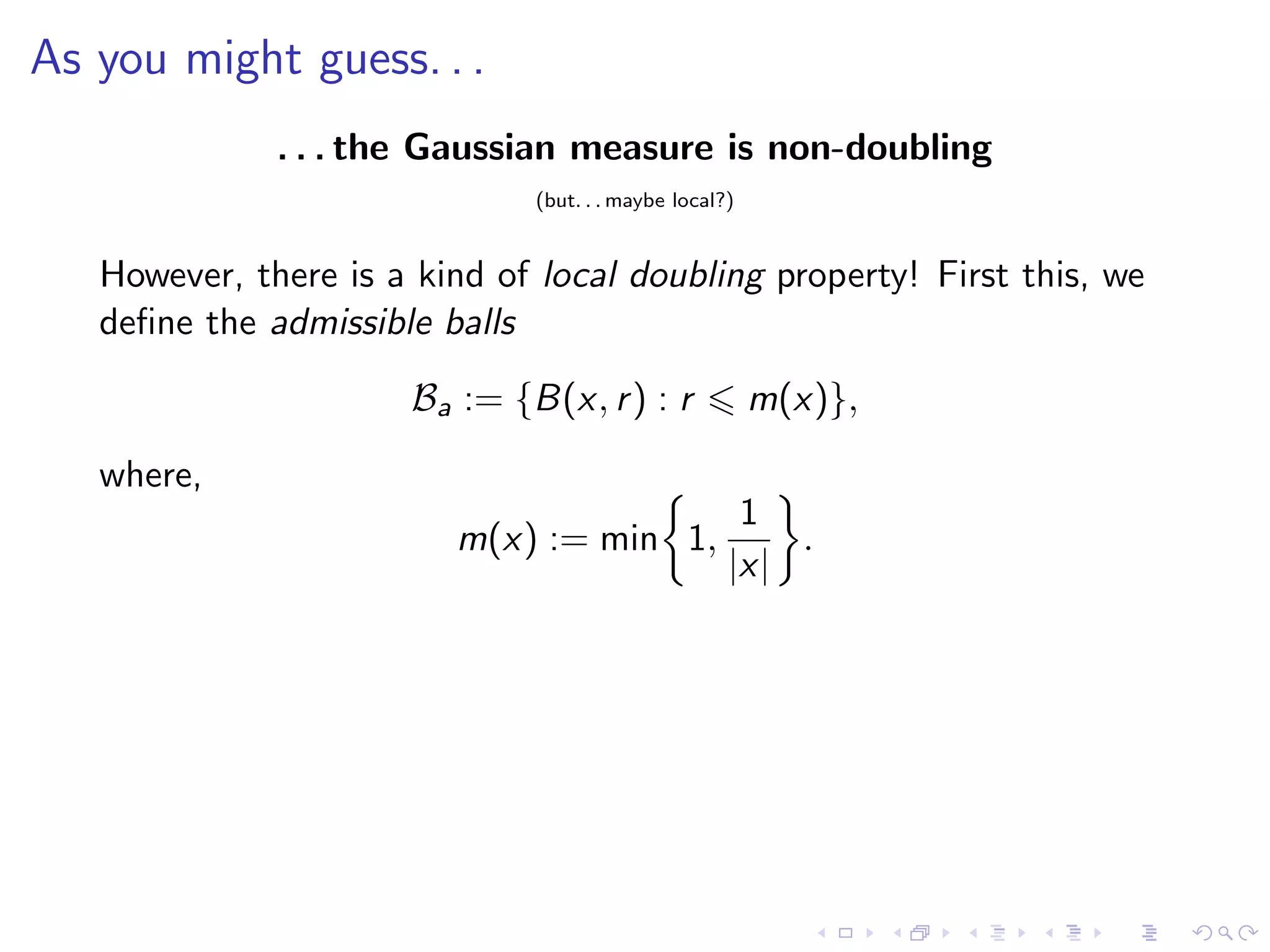

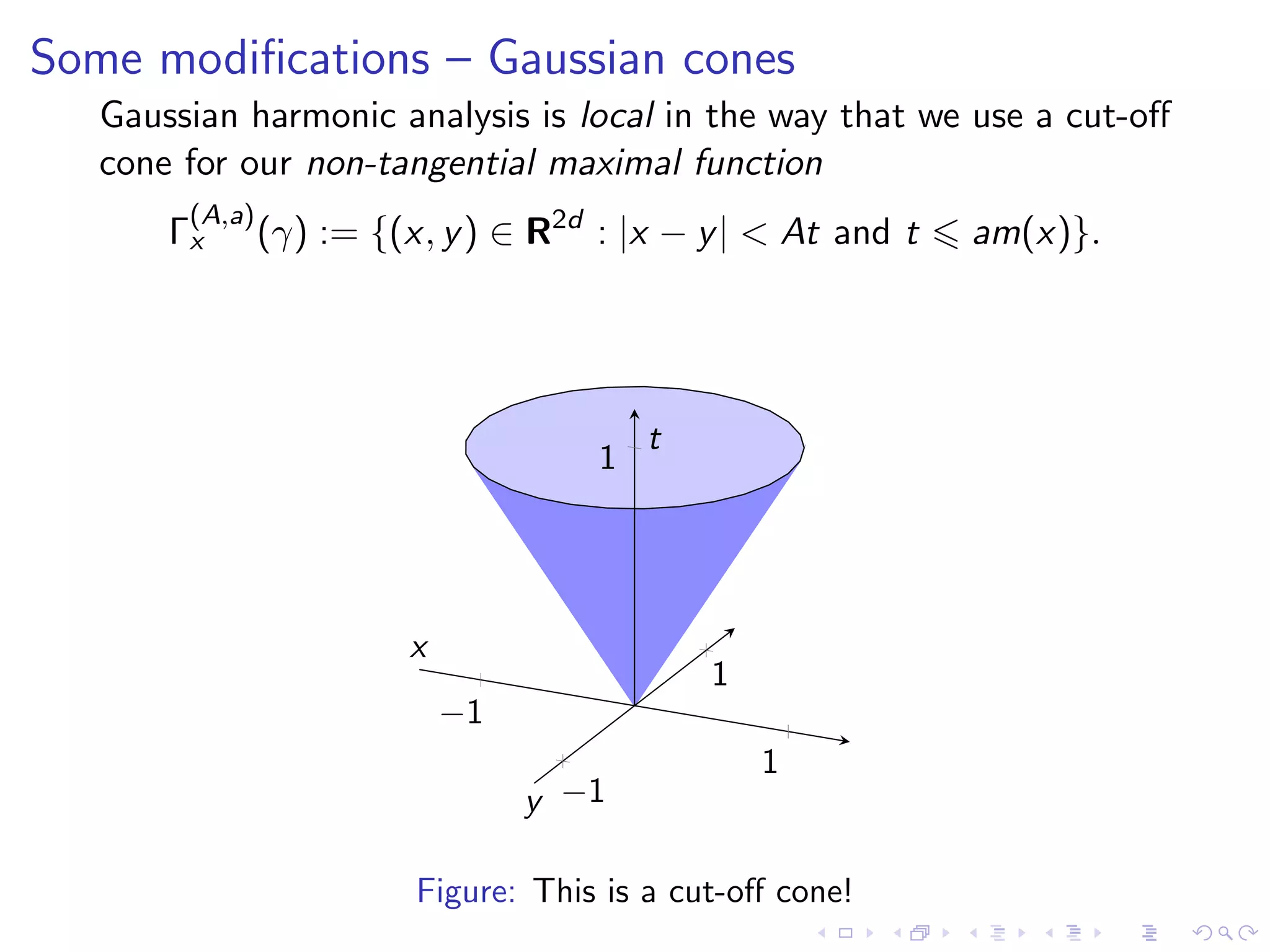

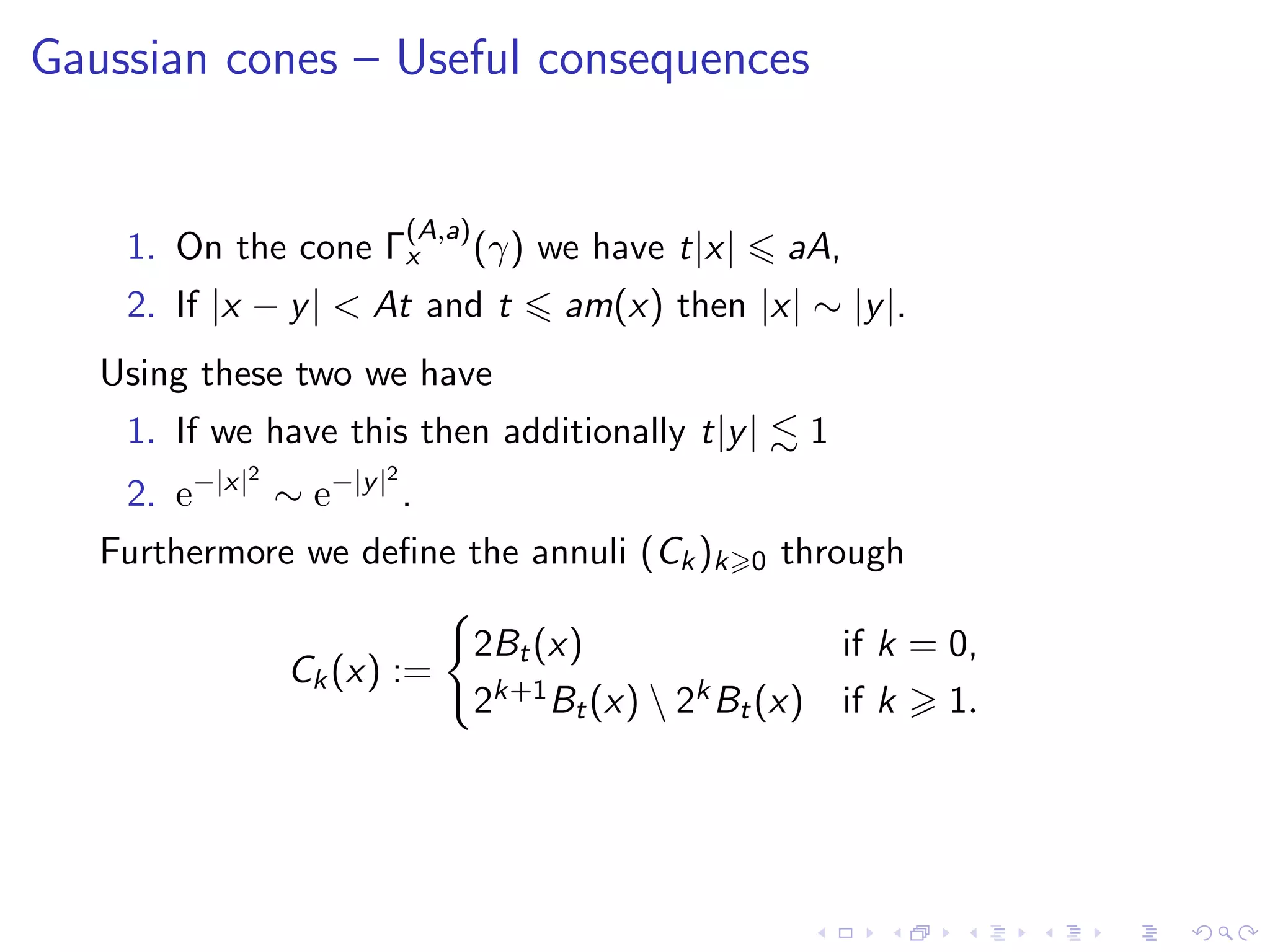

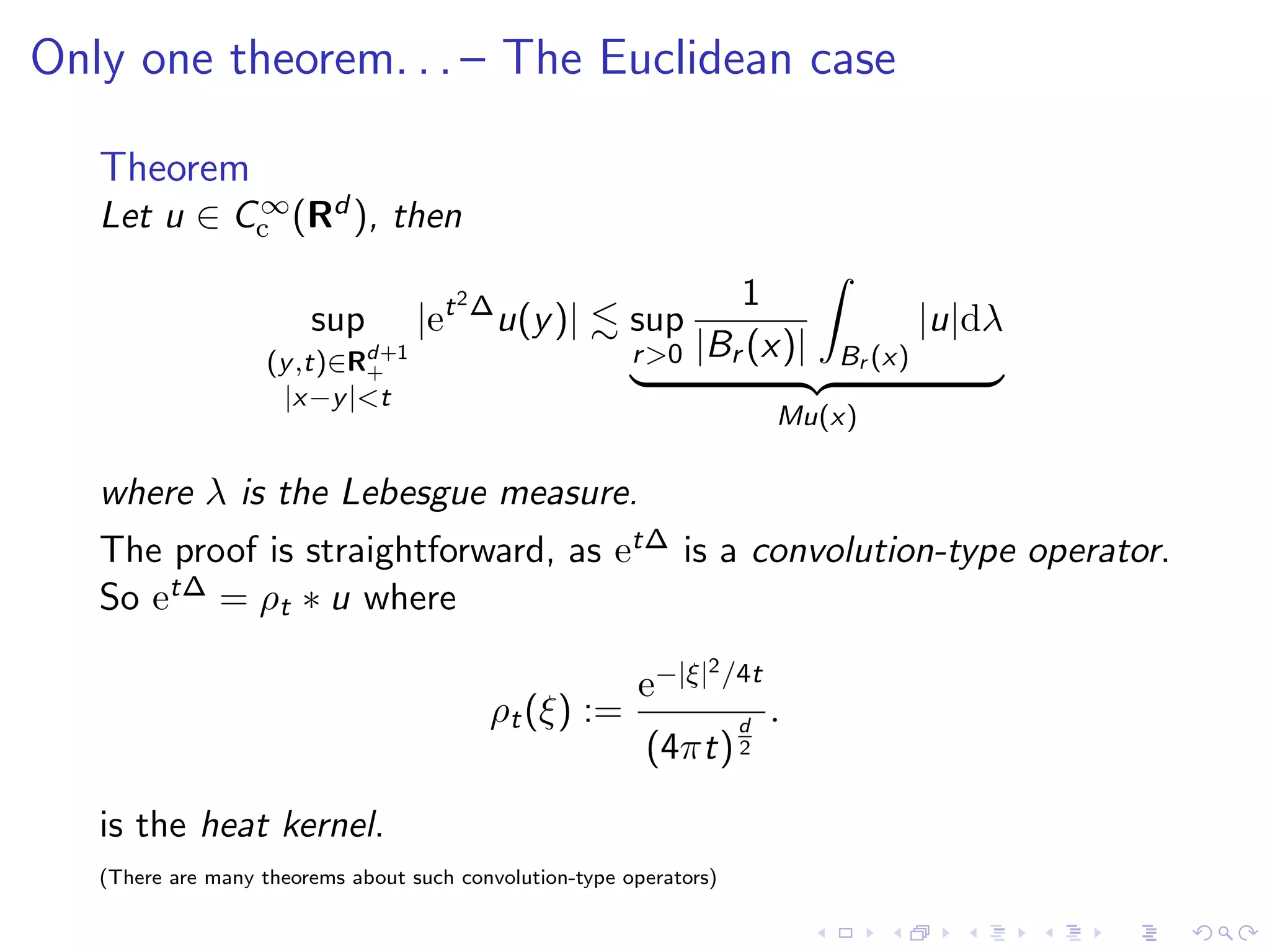

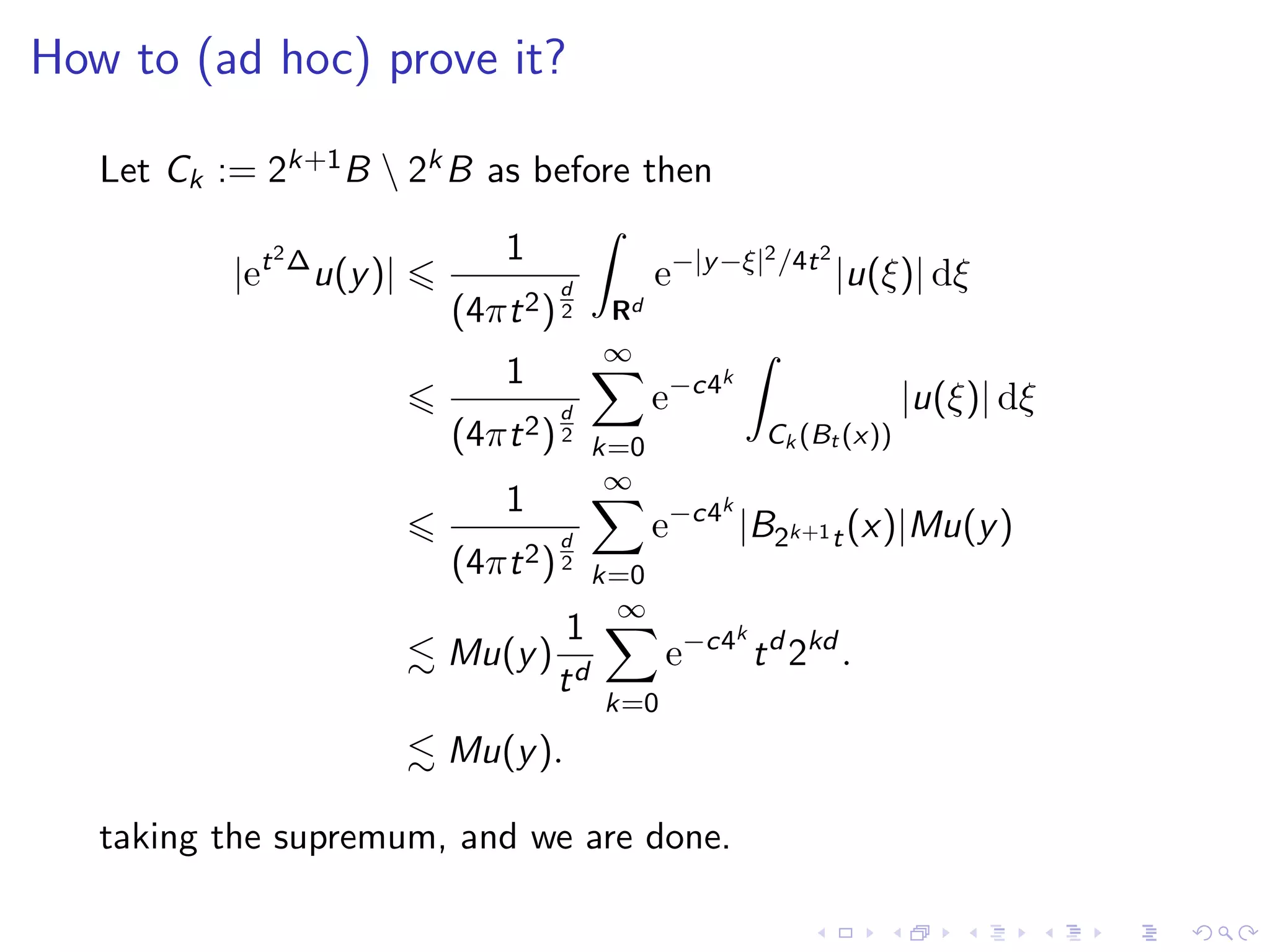

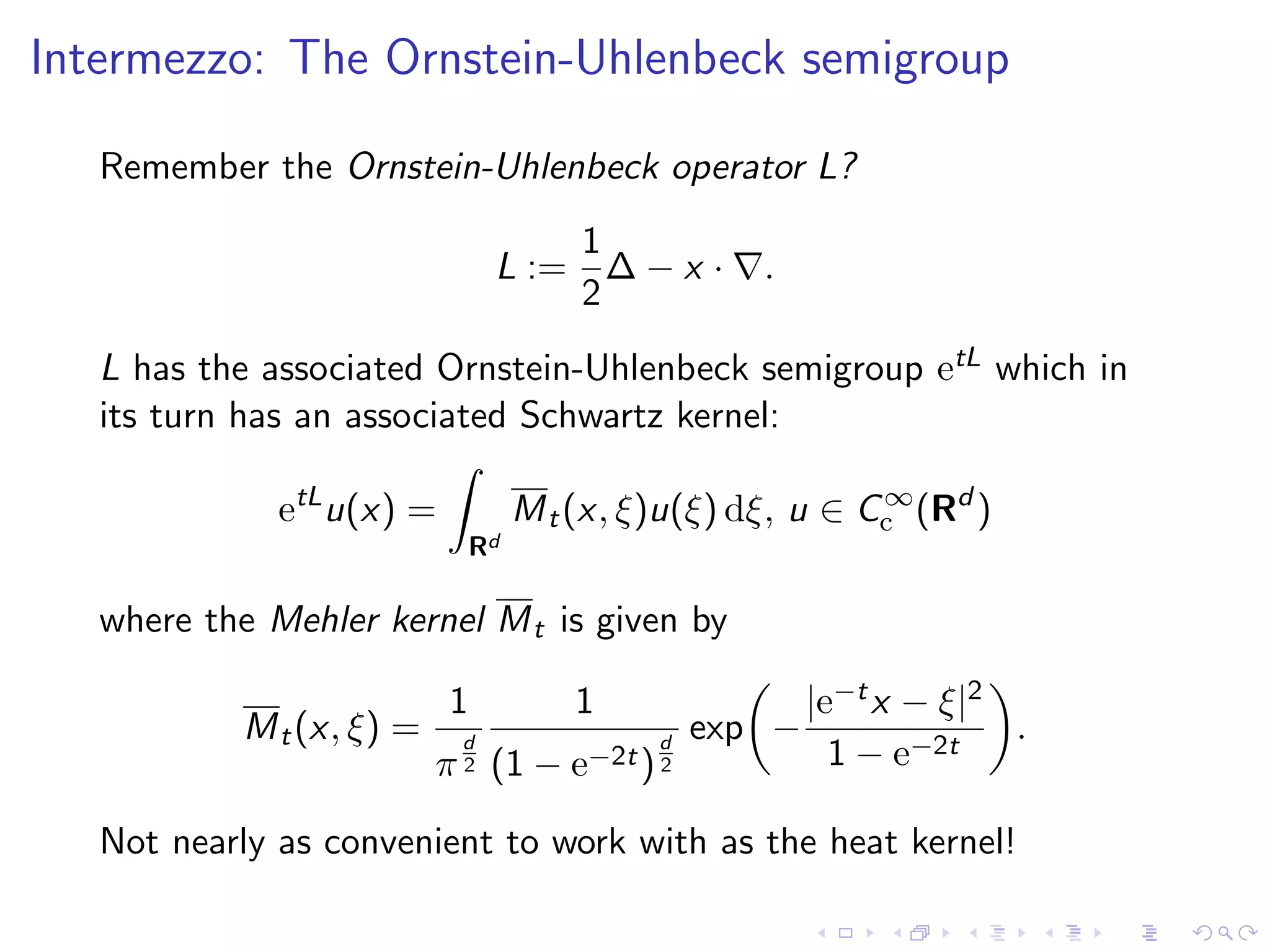

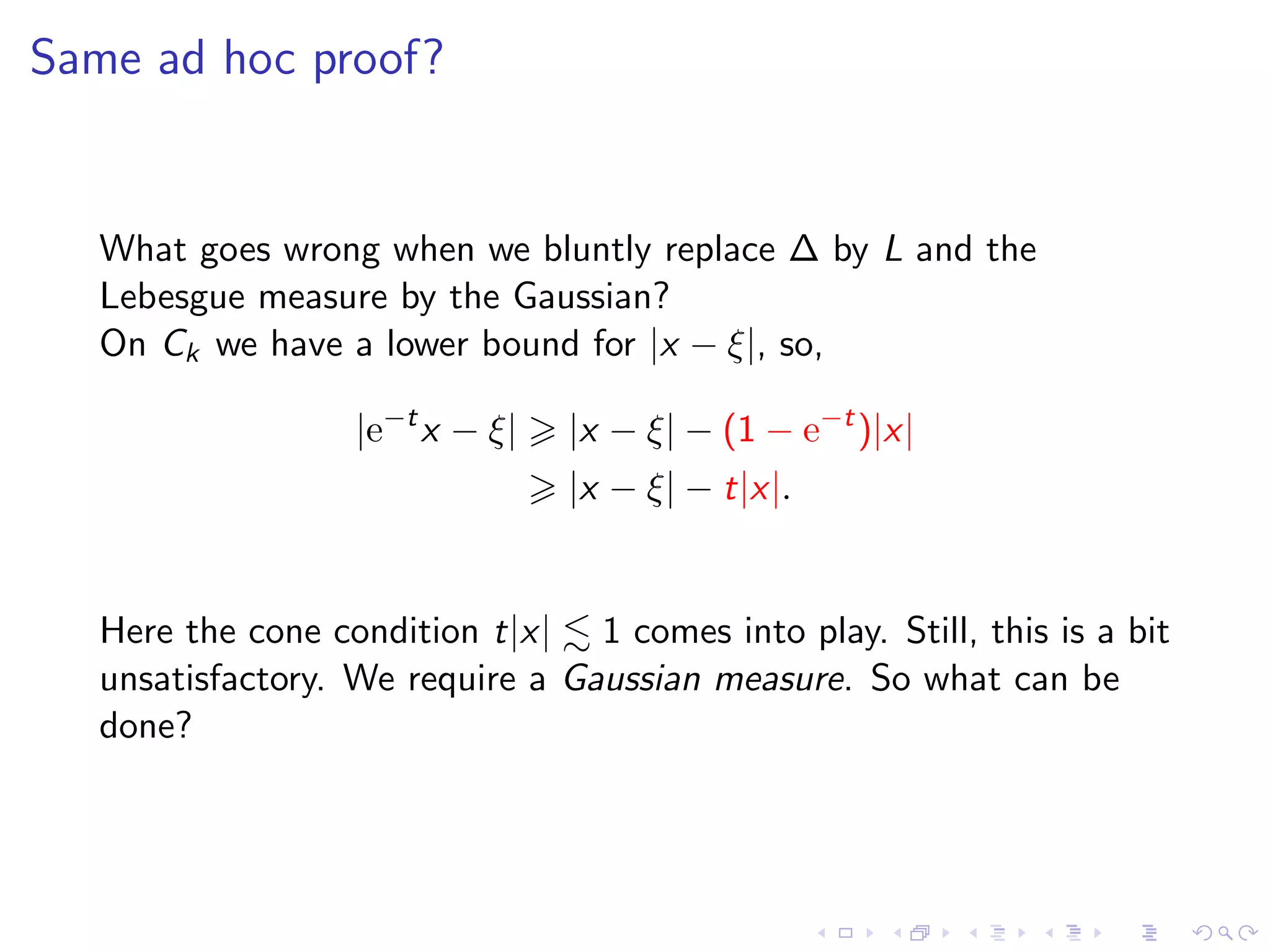

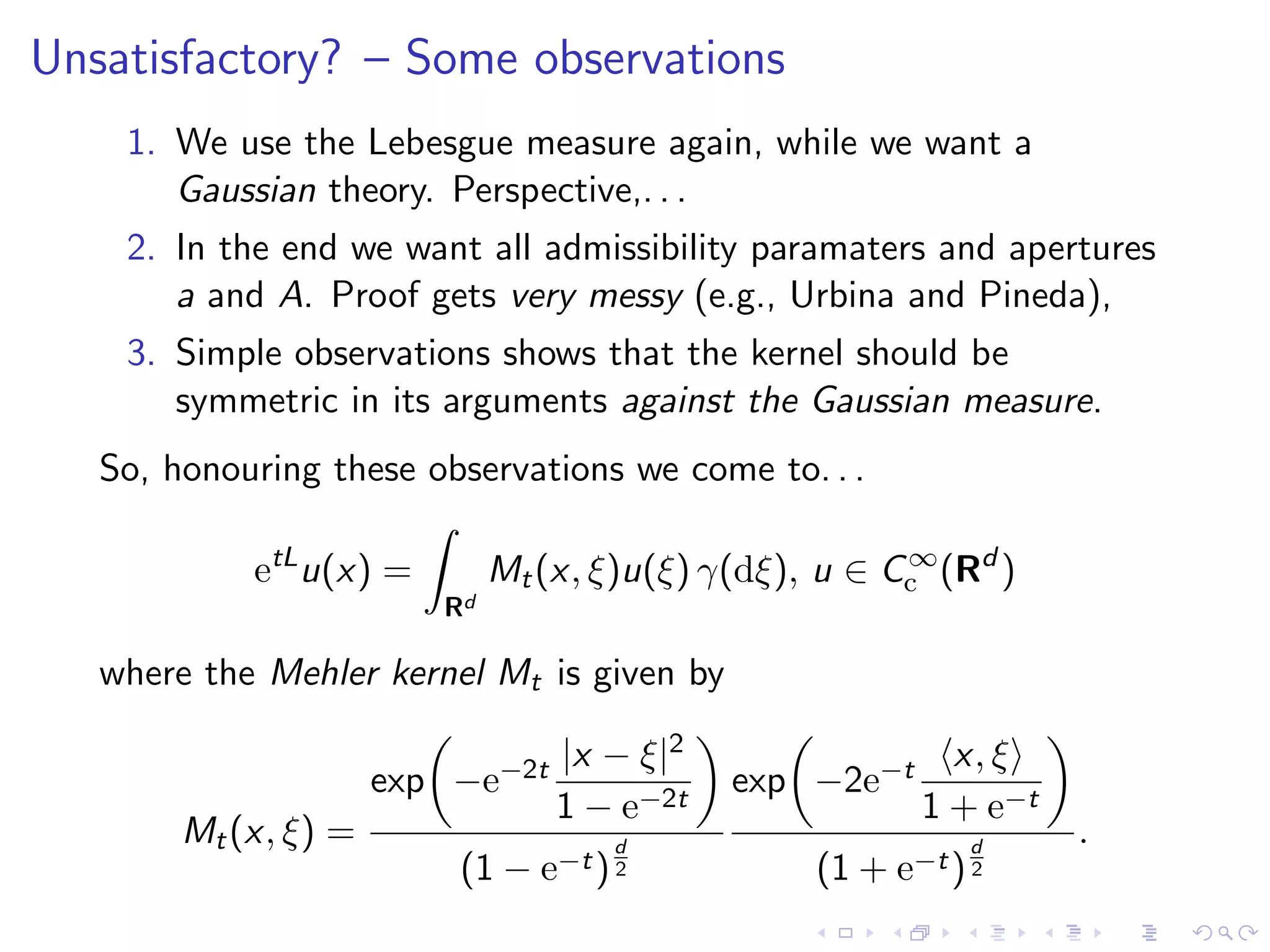

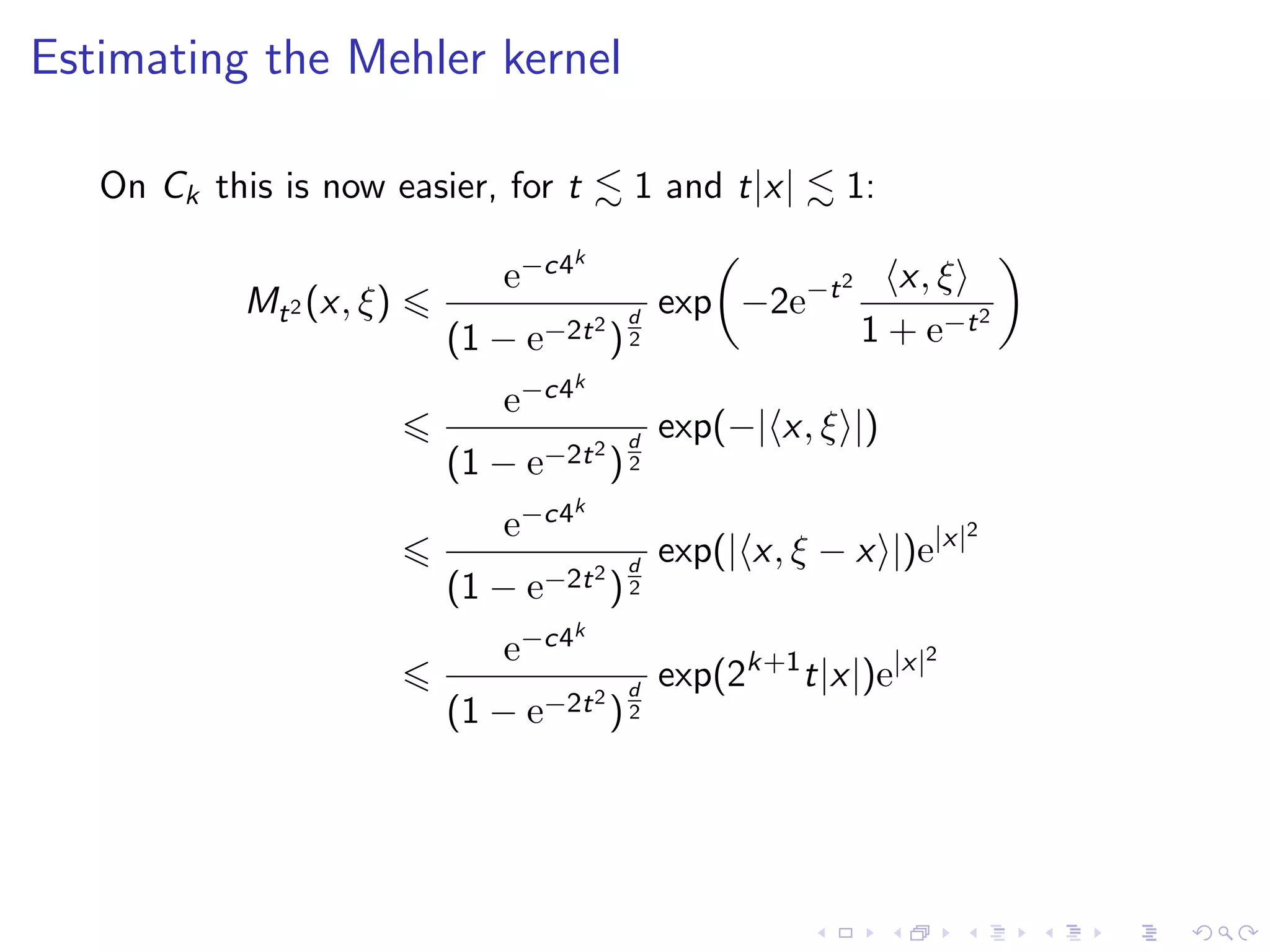

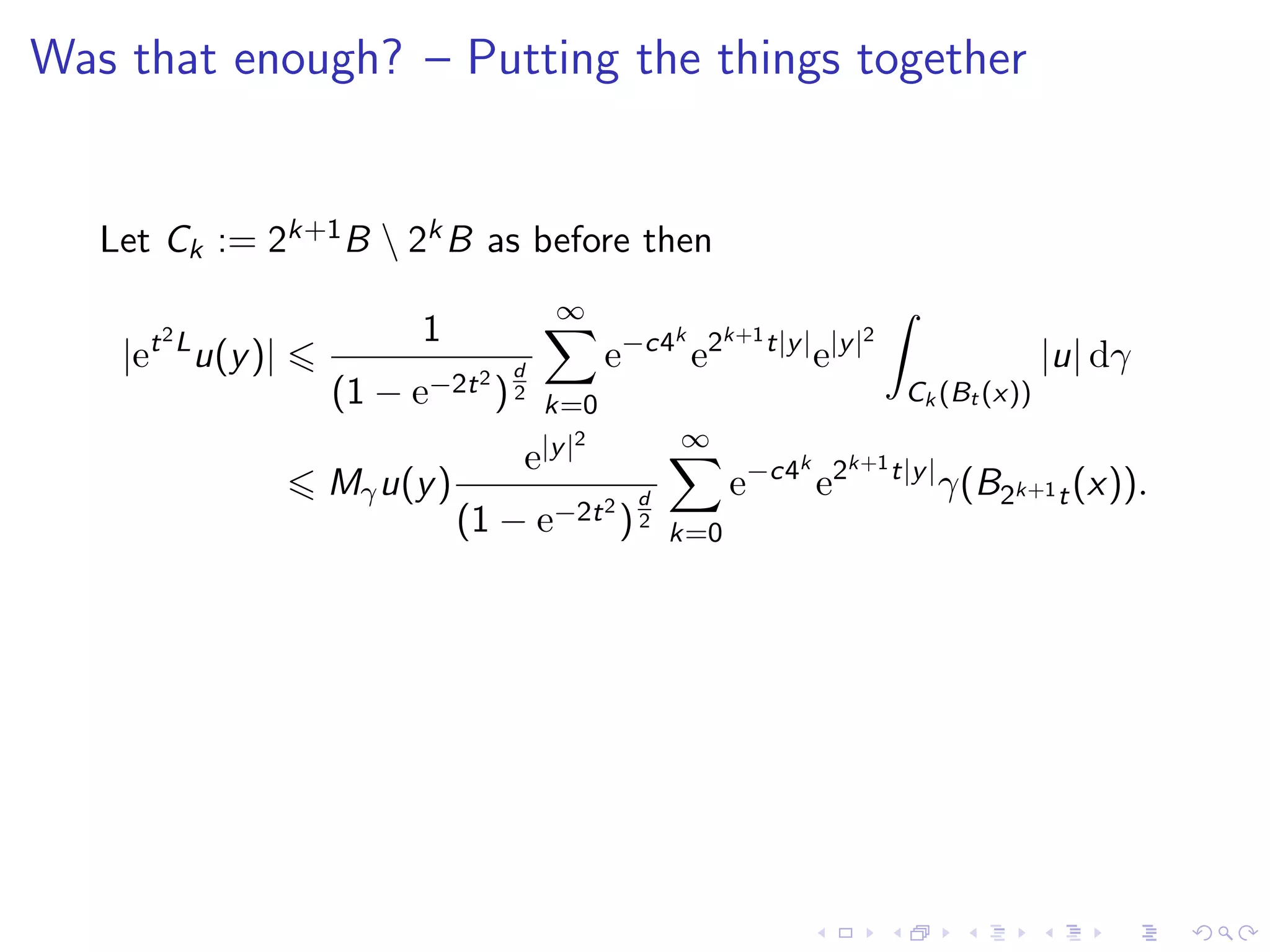

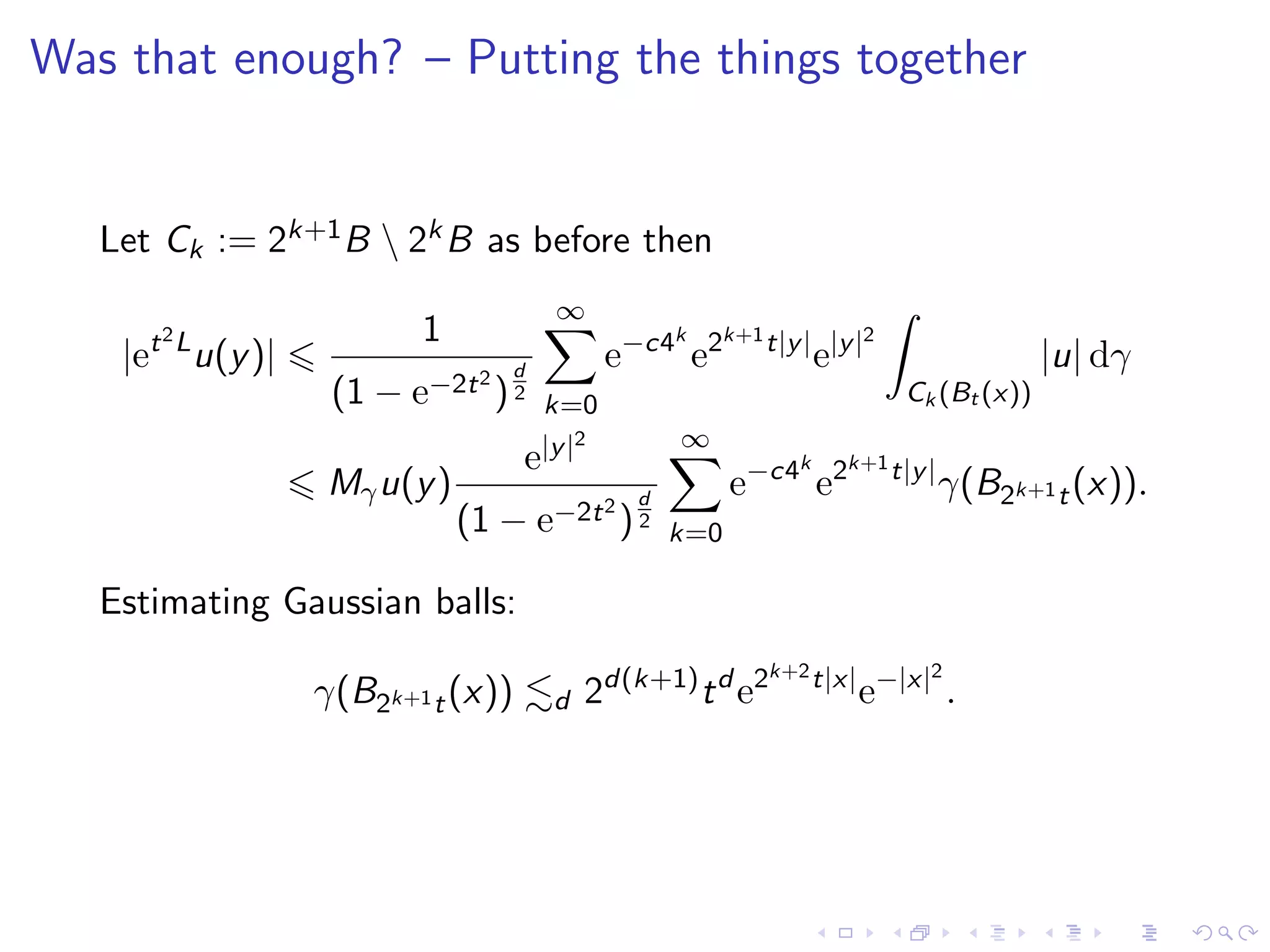

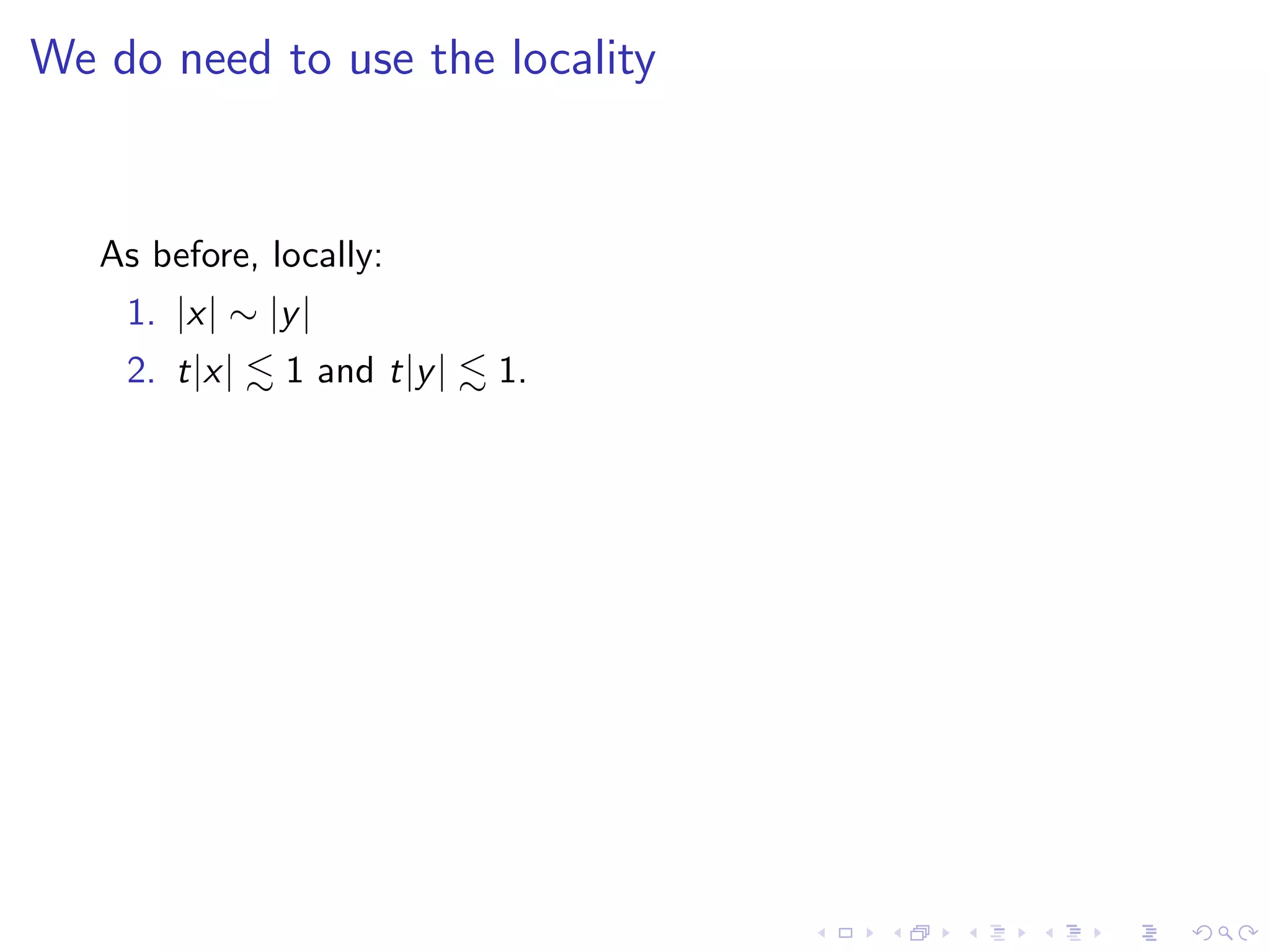

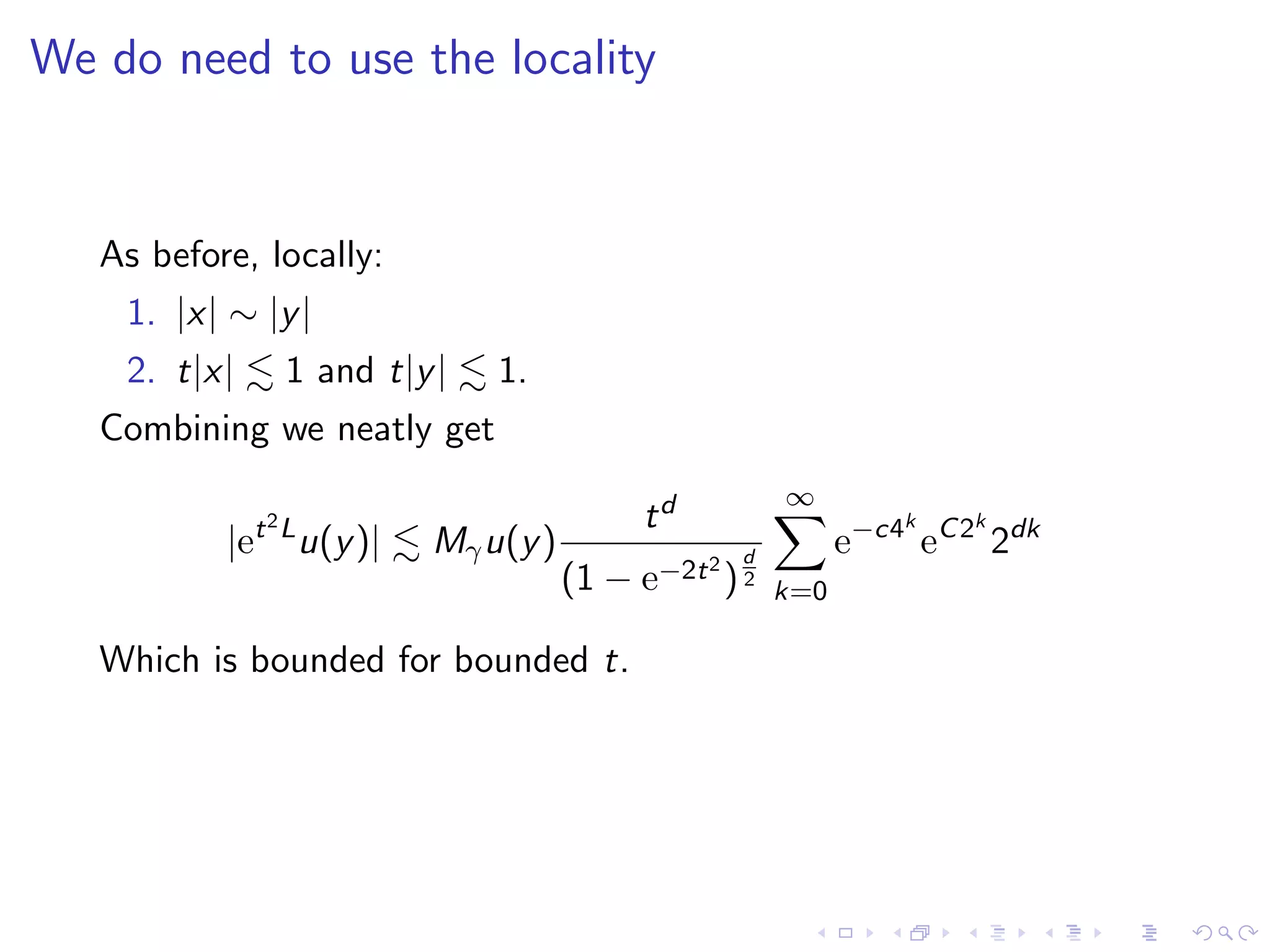

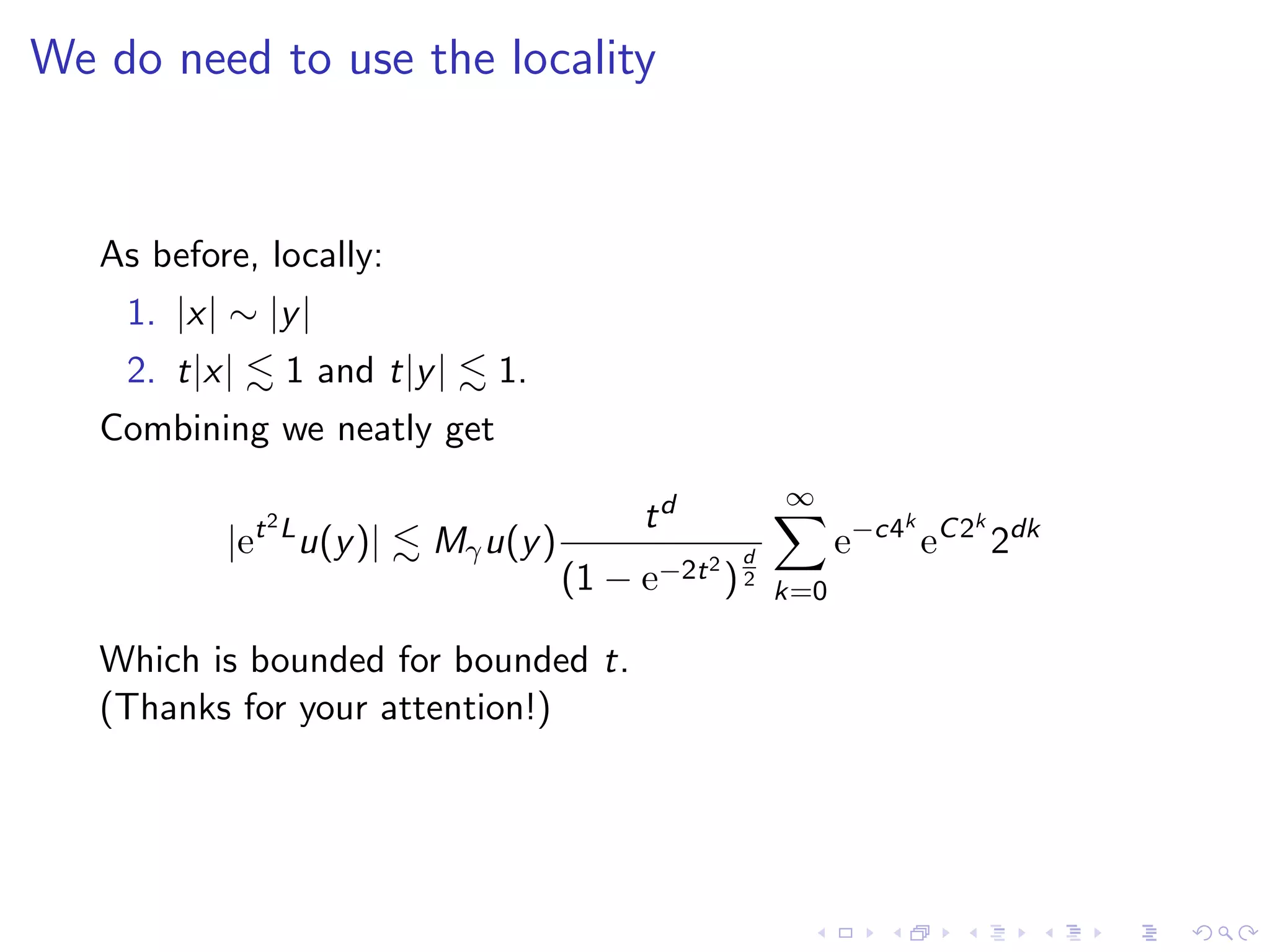

This document presents a summary of a talk on building a harmonic analytic theory for the Gaussian measure and the Ornstein-Uhlenbeck operator. It discusses how the Gaussian measure is non-doubling but satisfies a local doubling property. It introduces Gaussian cones and shows how they allow proving maximal function estimates for the Ornstein-Uhlenbeck semigroup in a similar way as for the heat semigroup. The talk outlines estimates for the Mehler kernel of the Ornstein-Uhlenbeck semigroup and combines them to obtain boundedness of the maximal function.