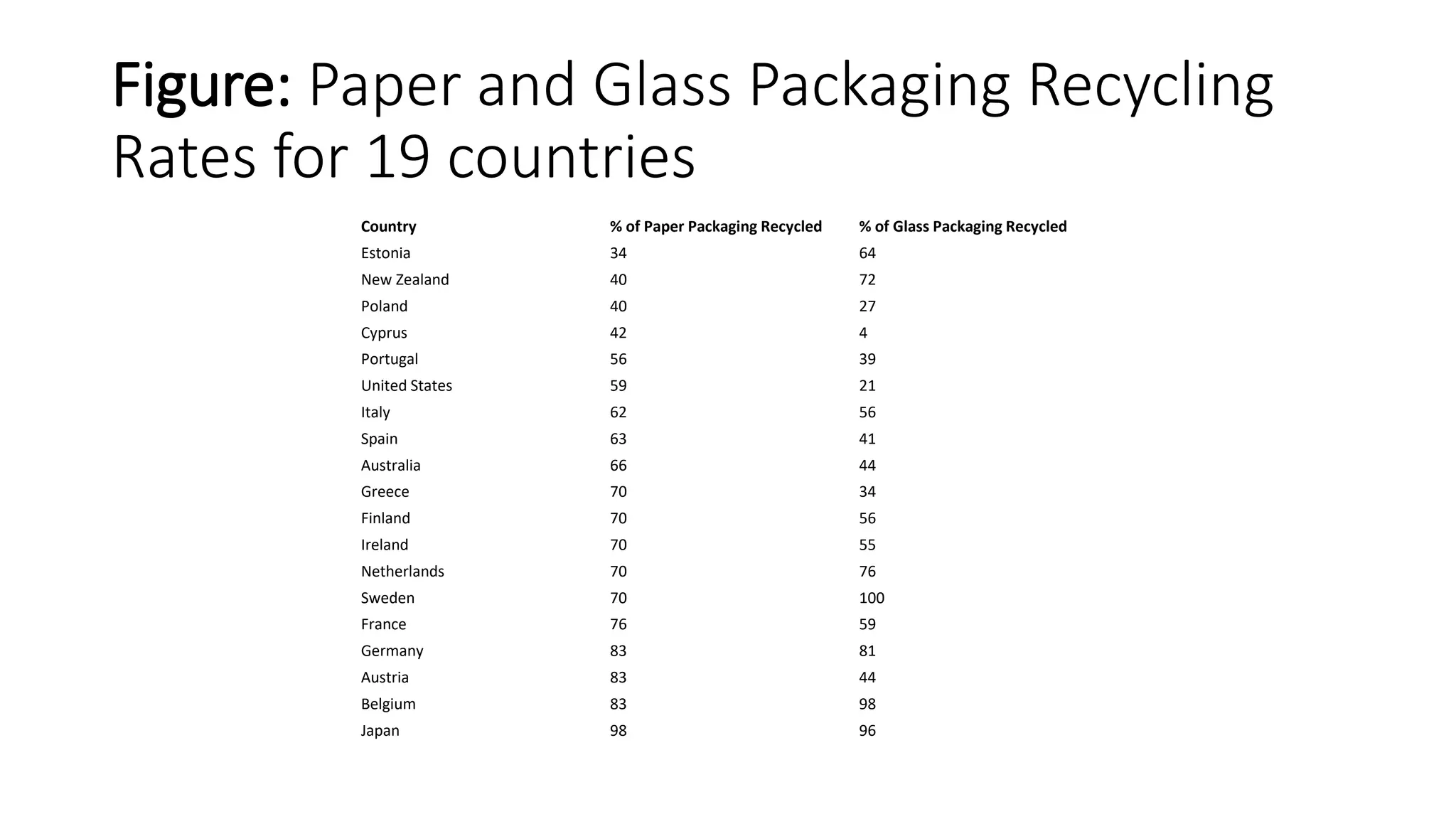

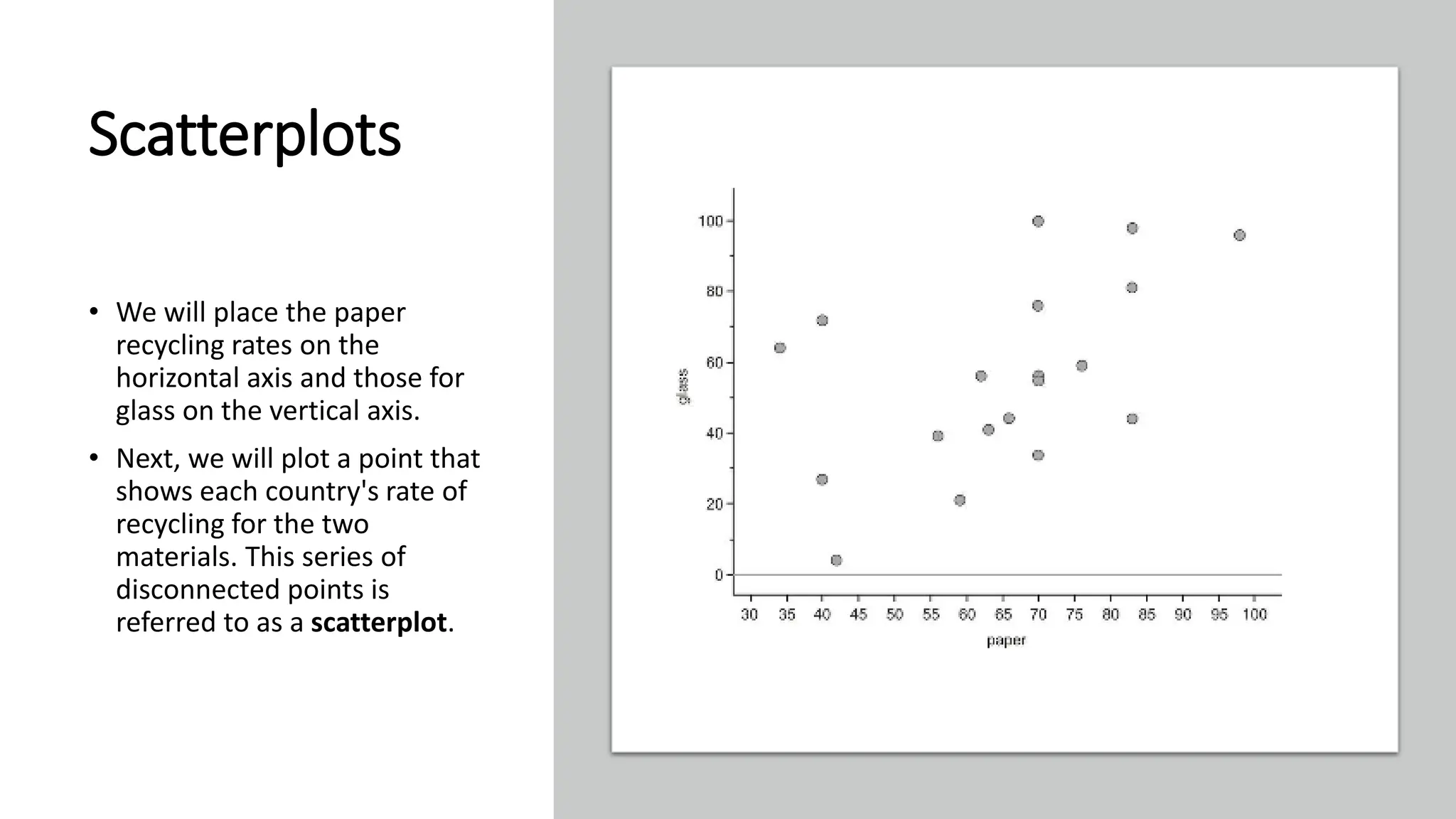

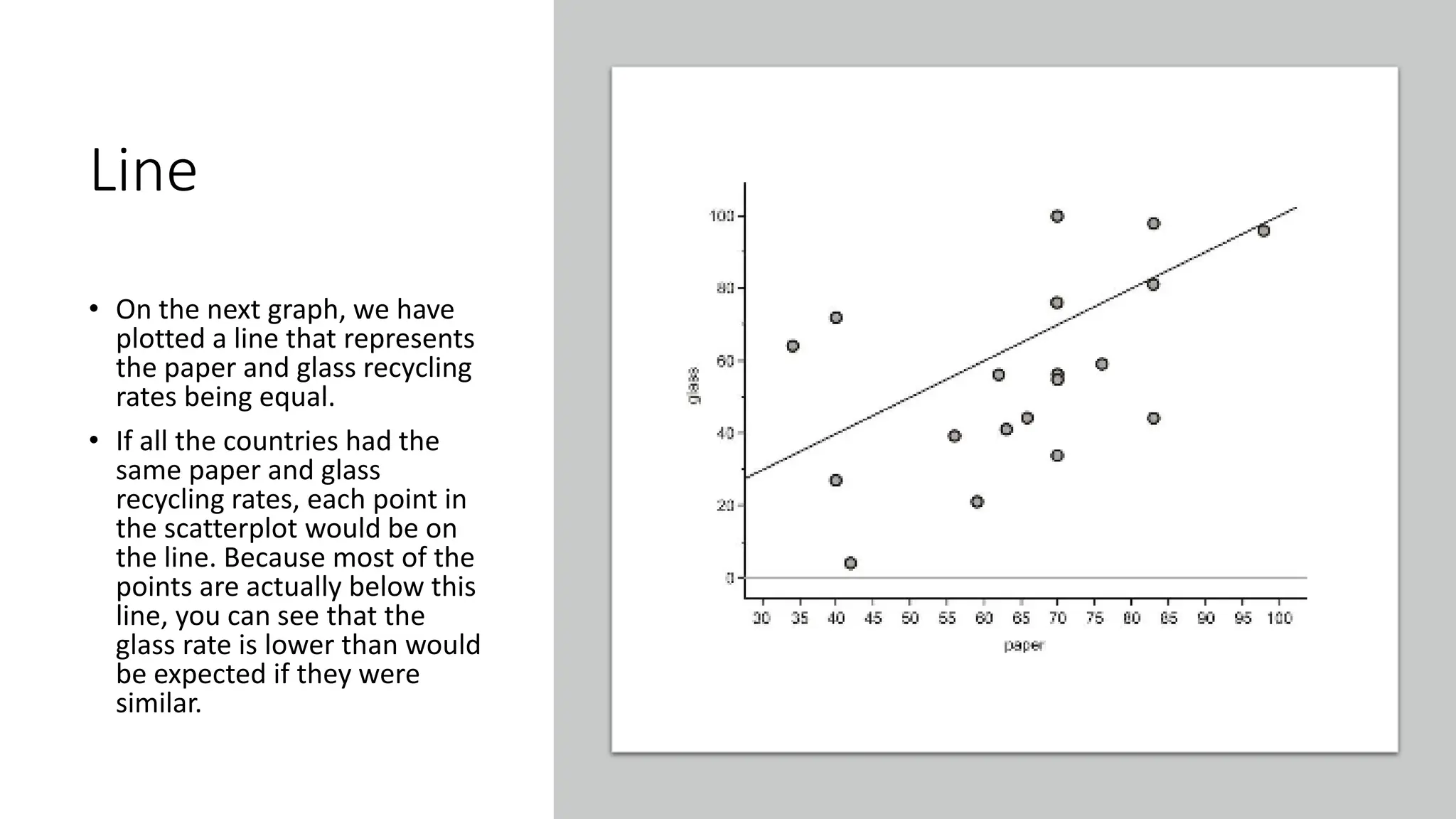

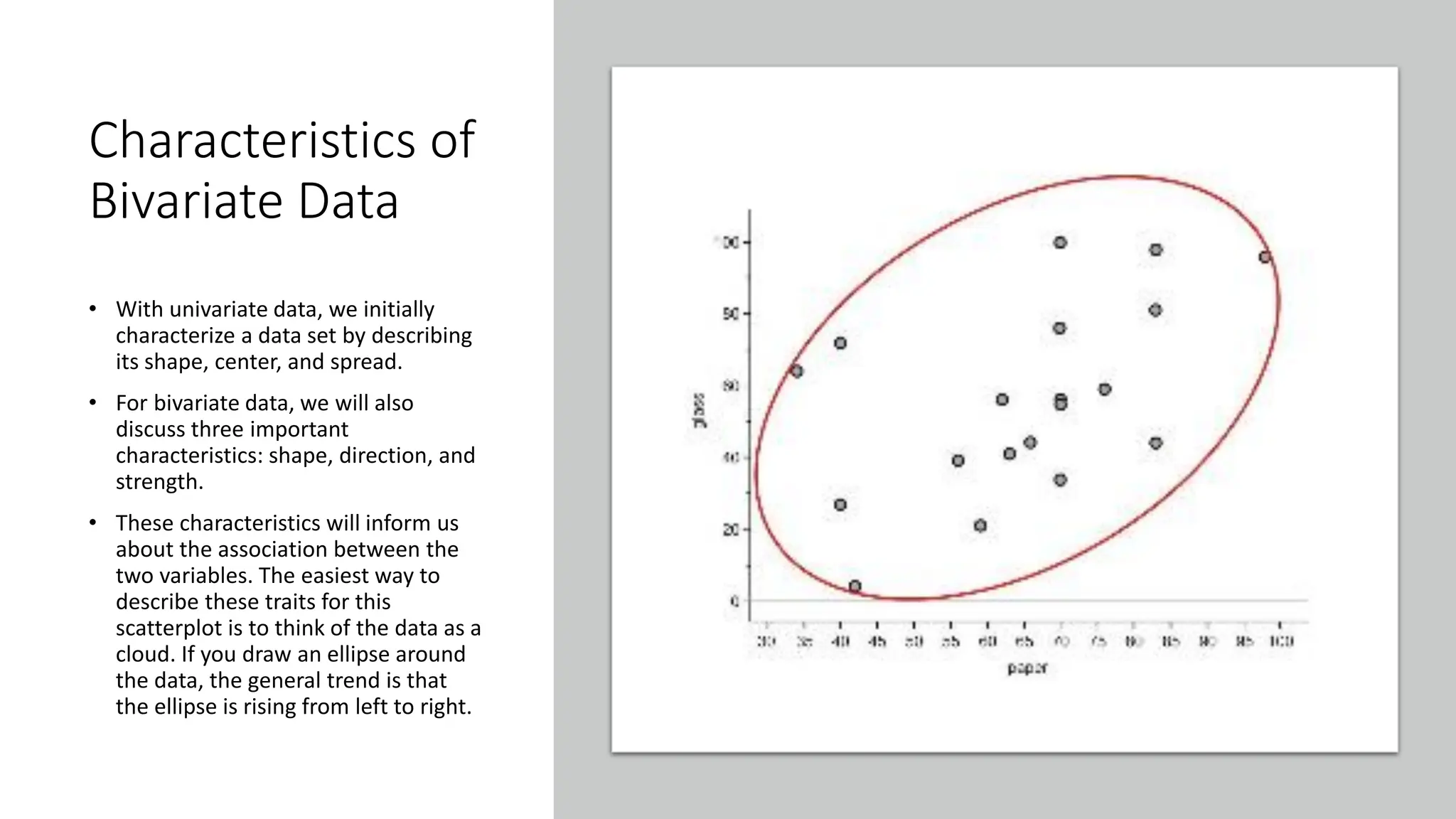

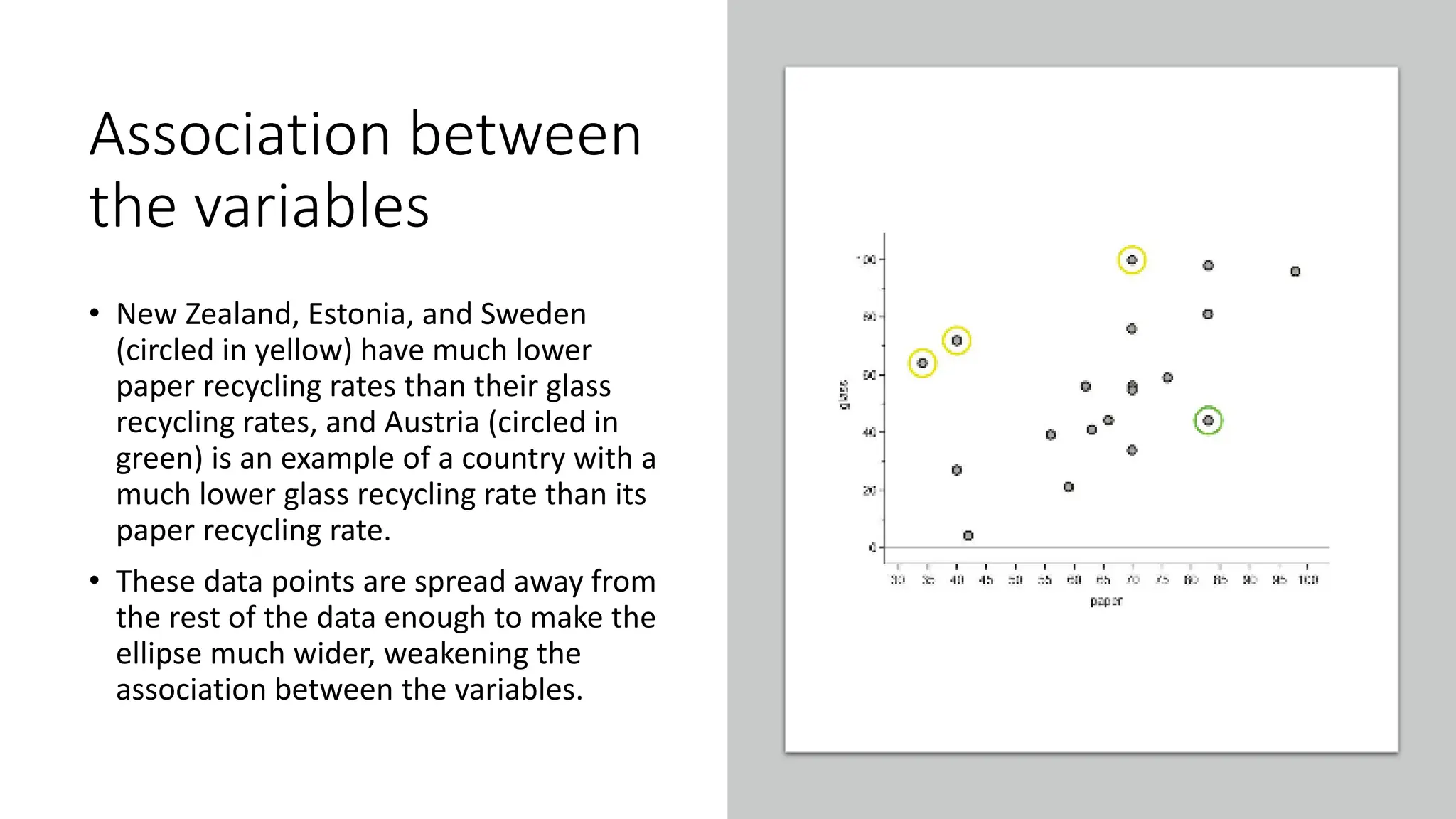

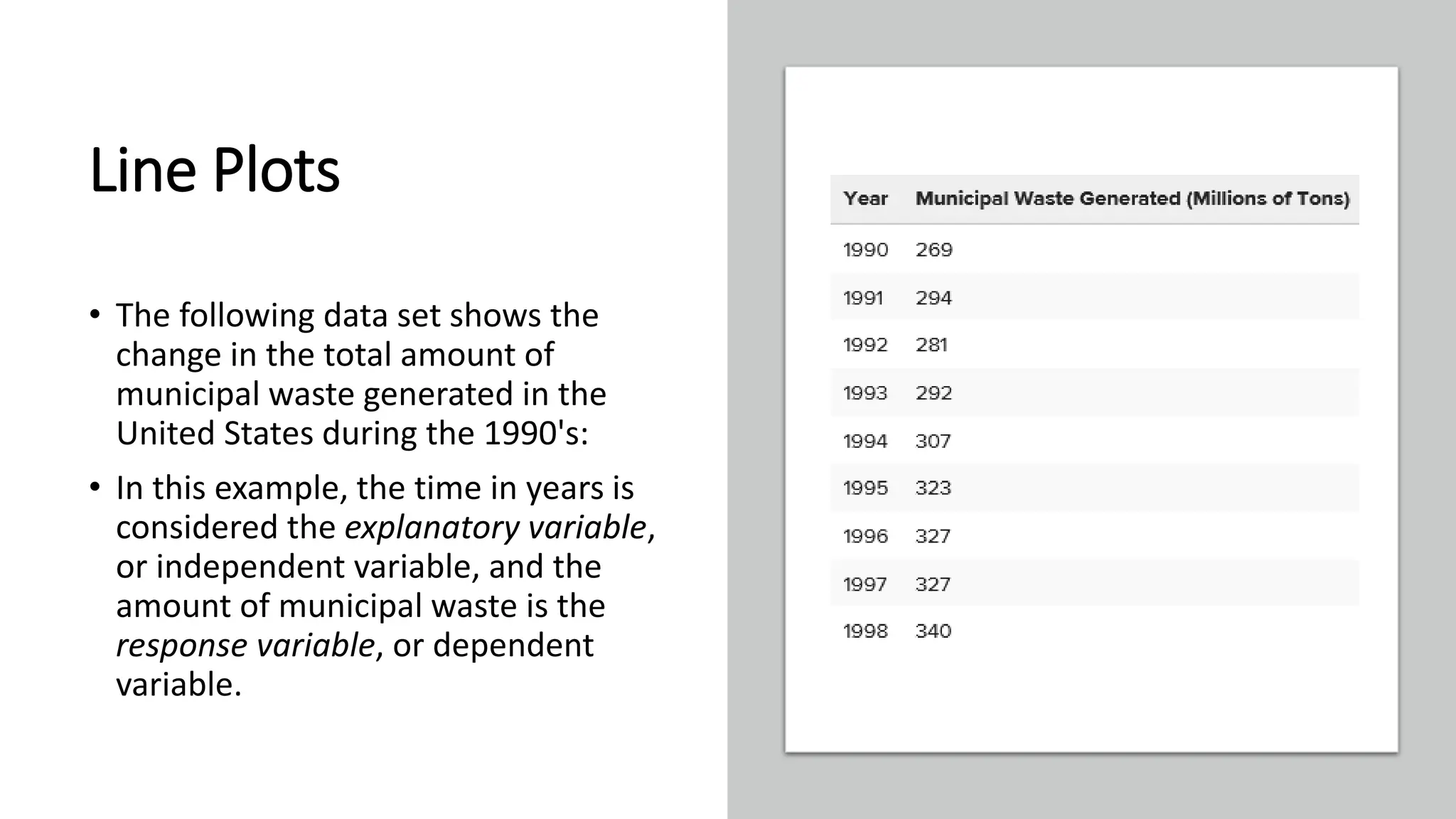

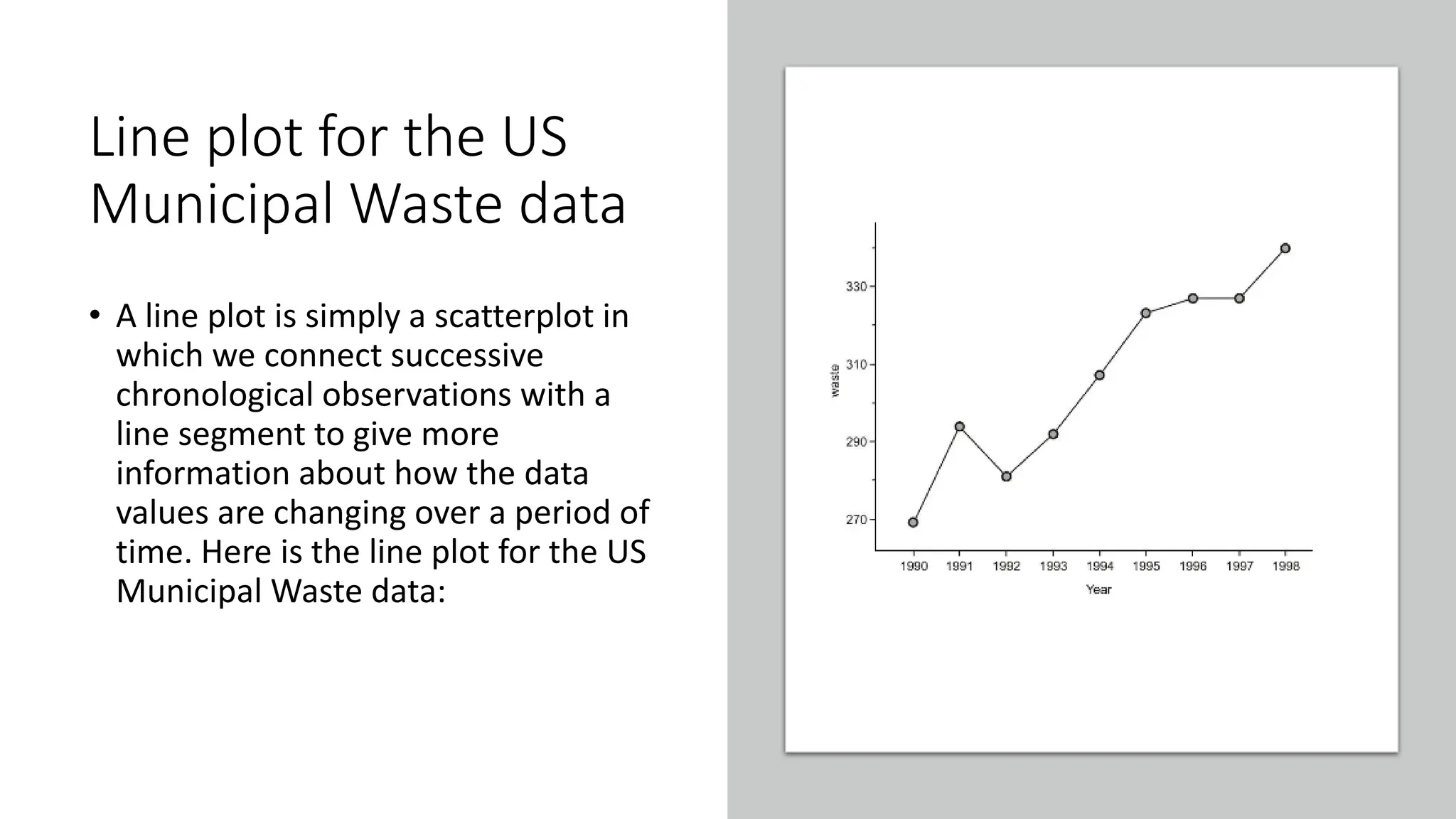

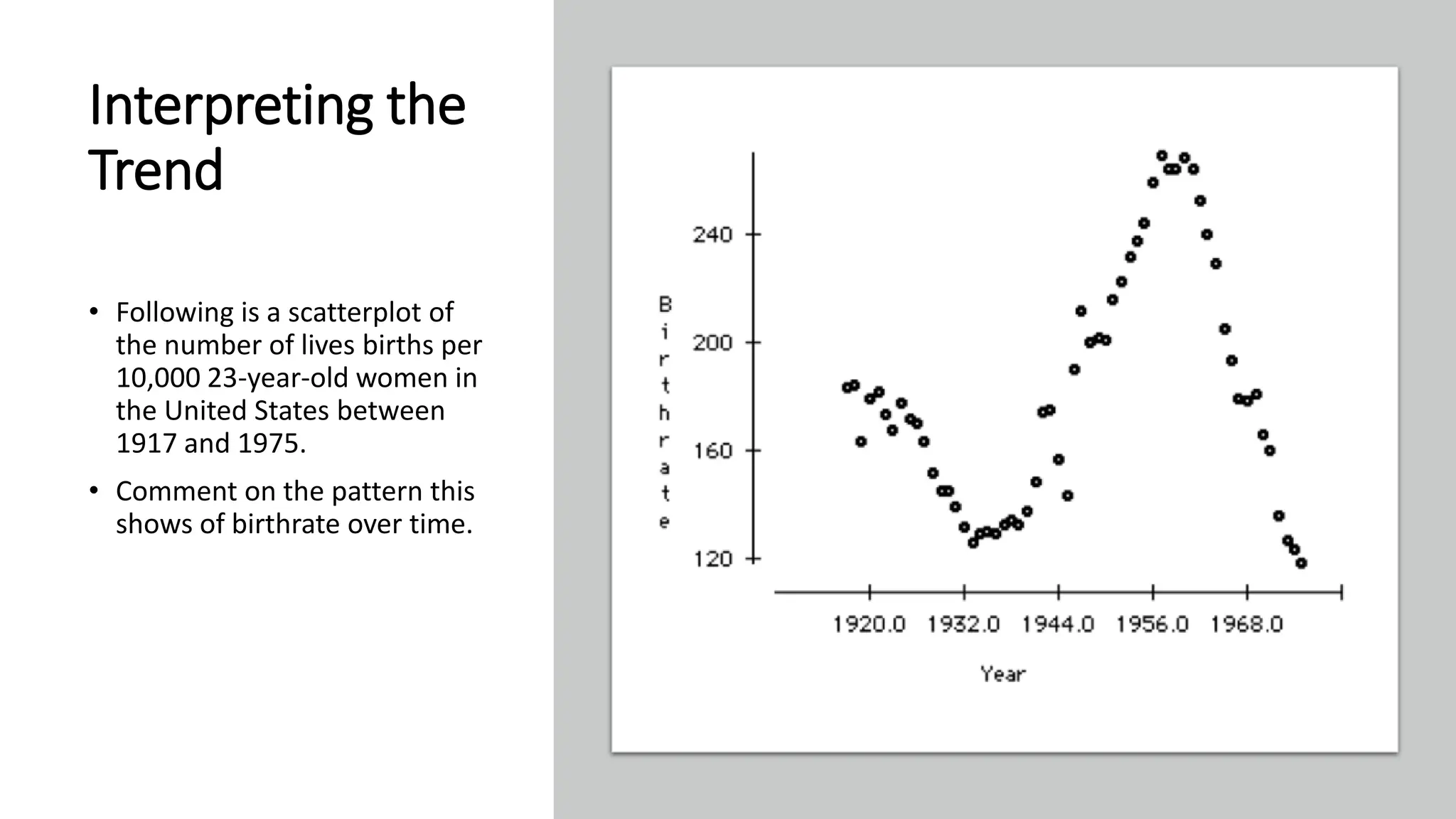

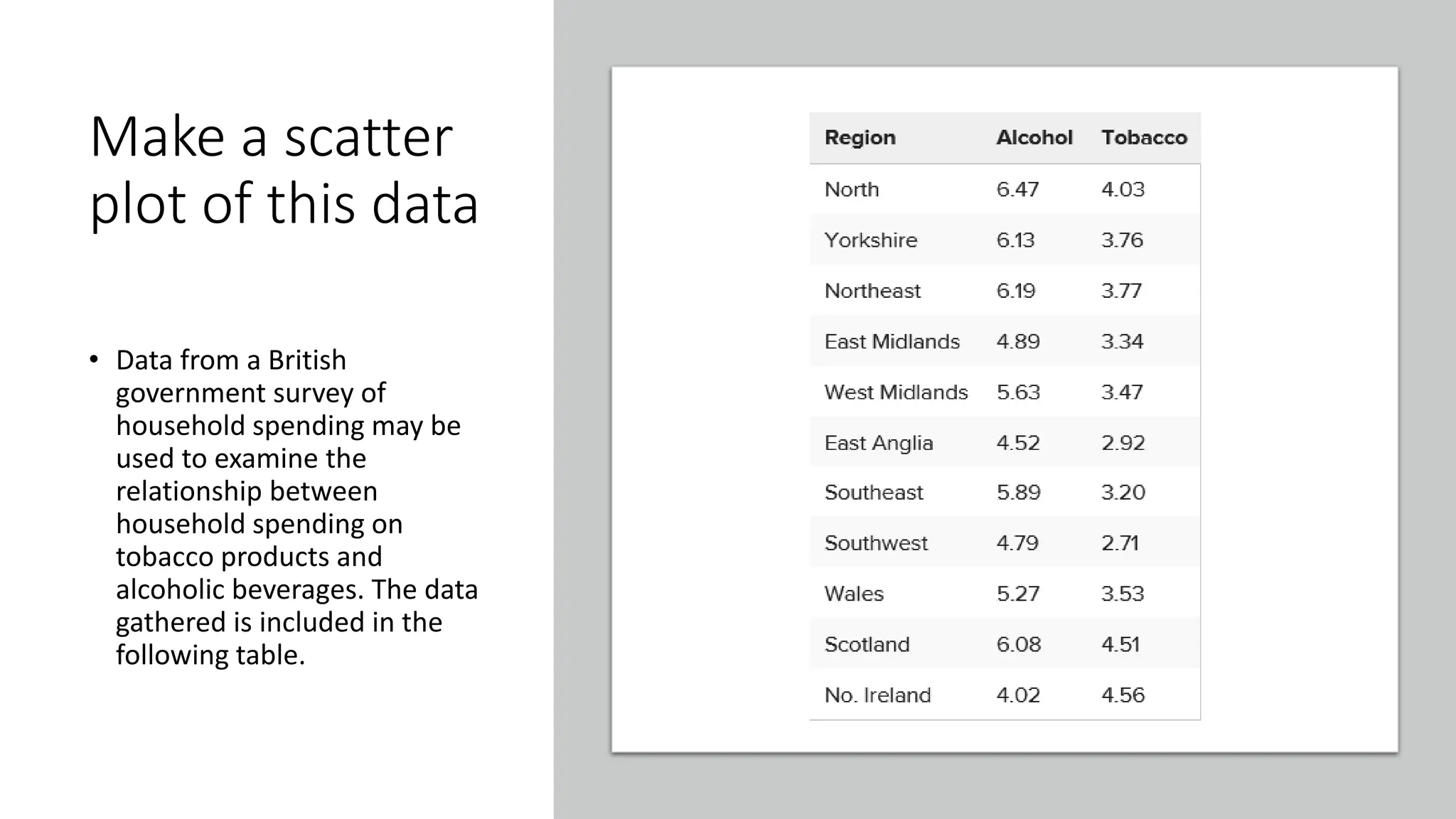

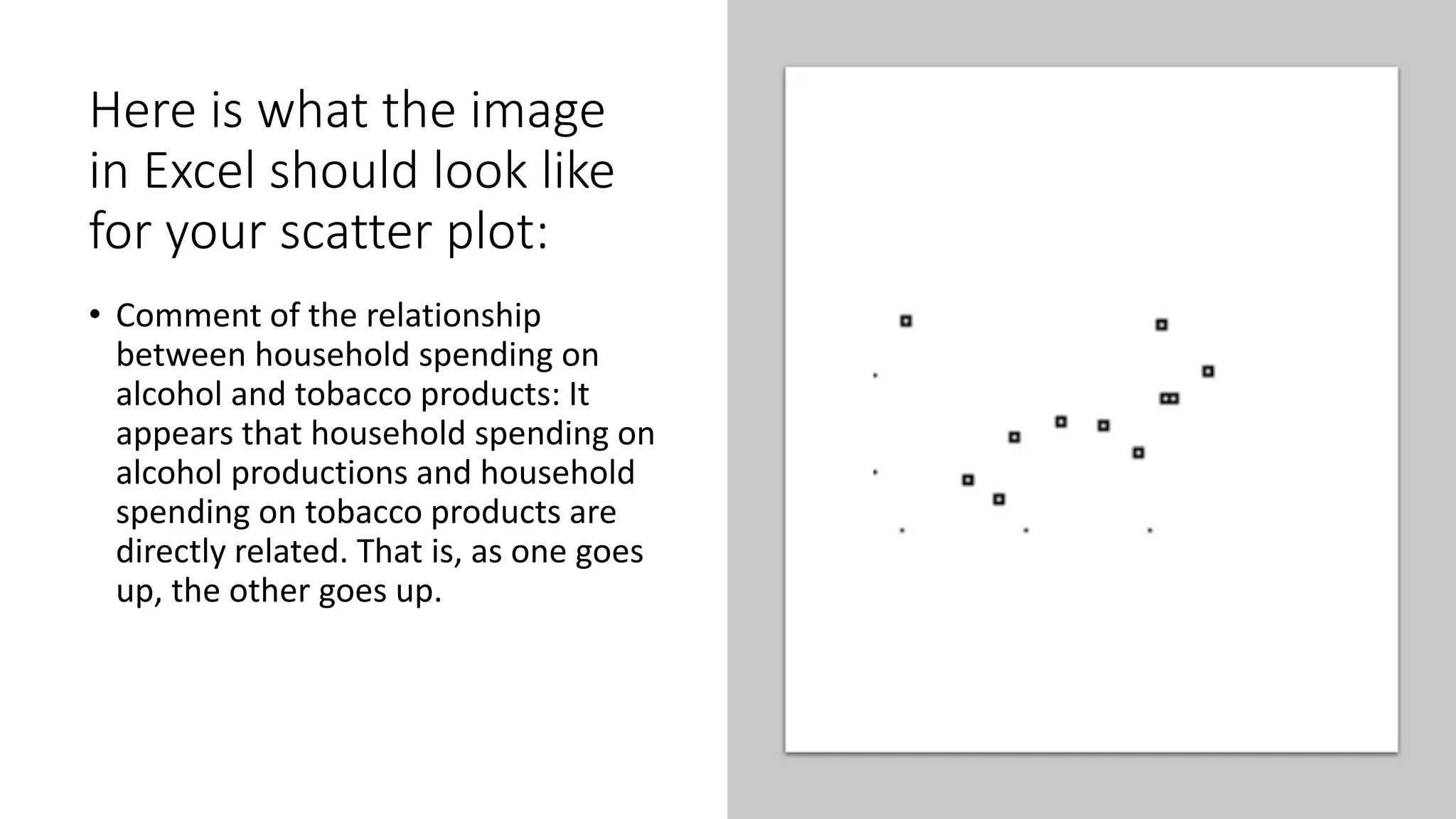

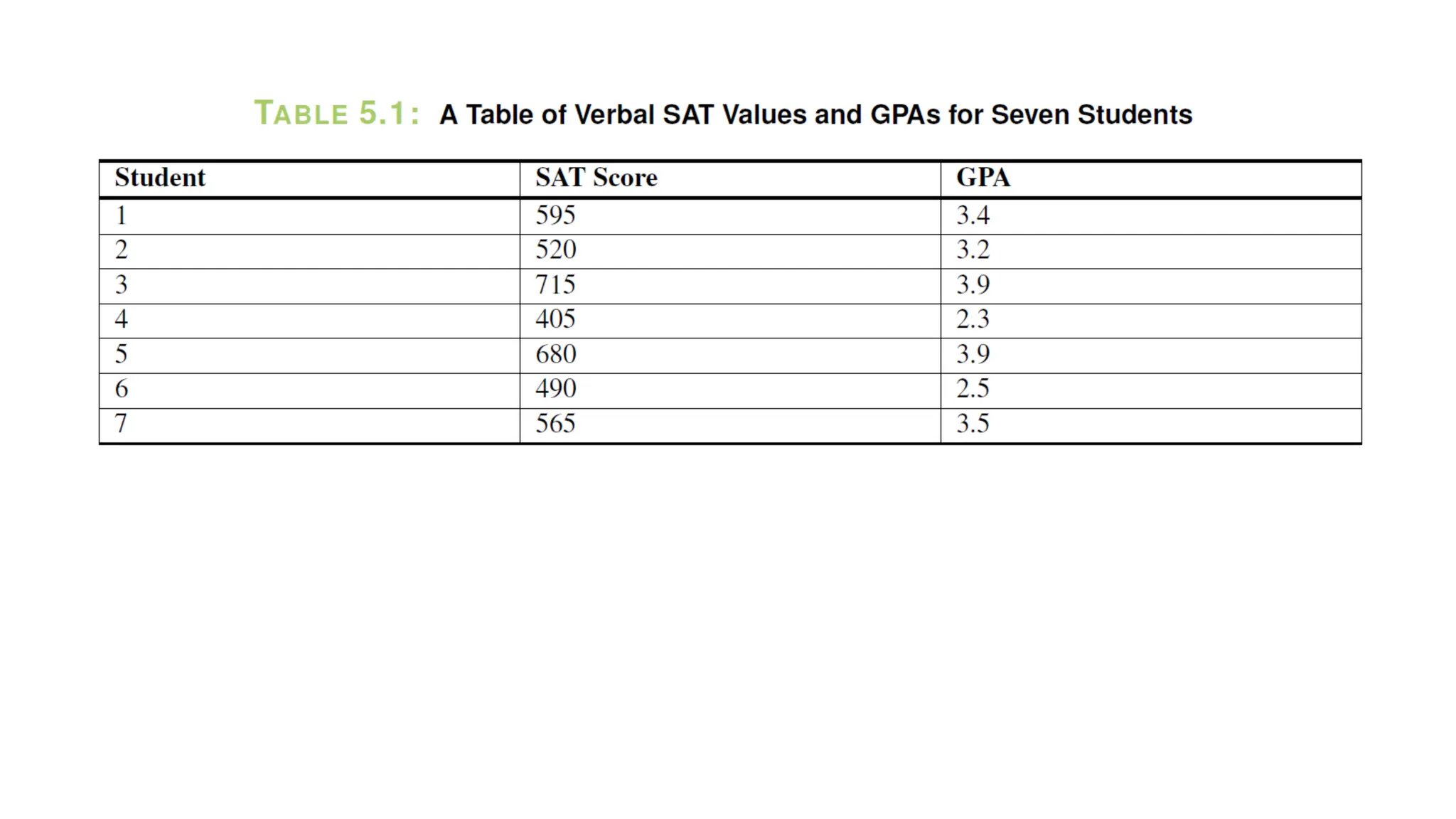

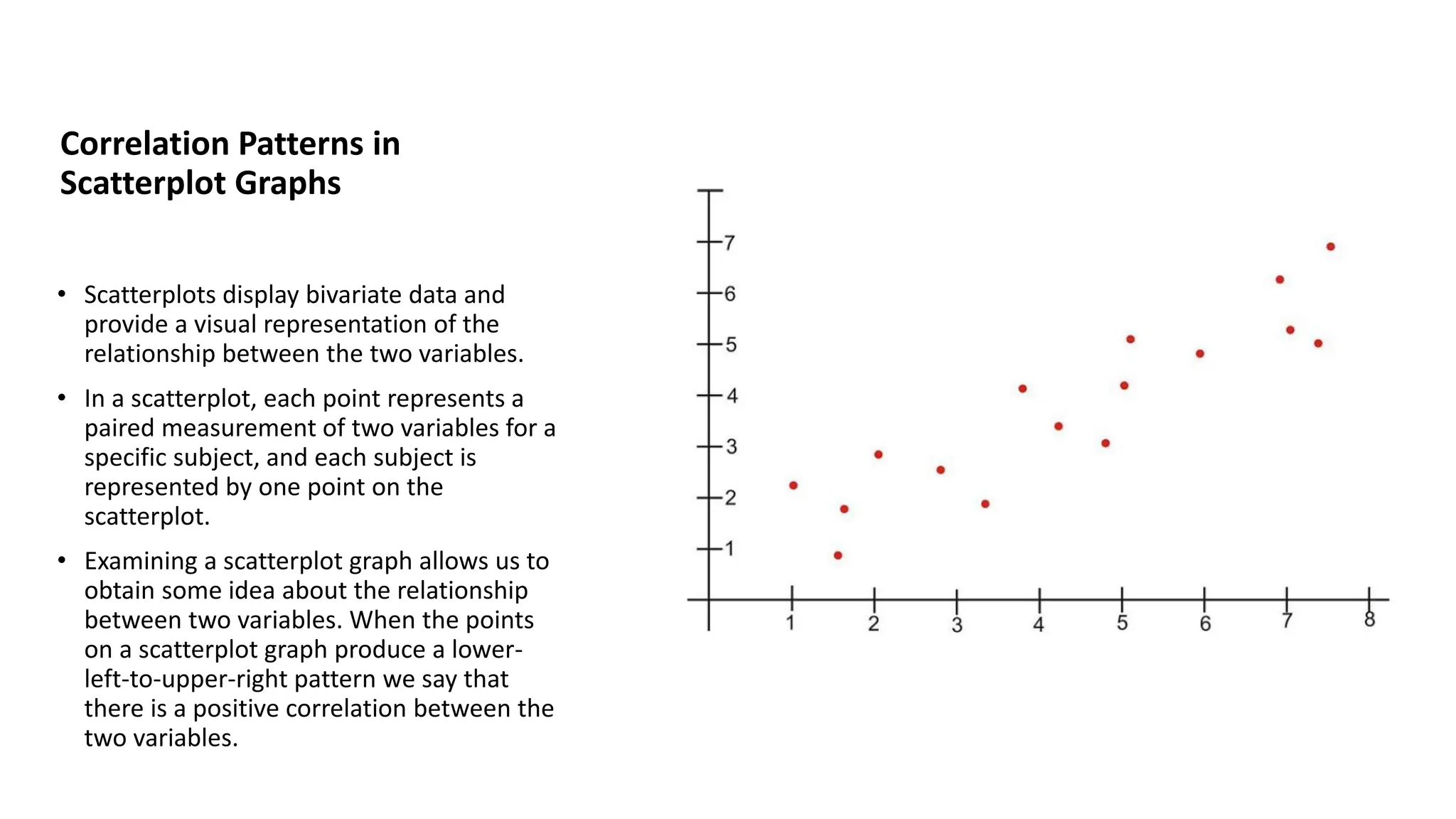

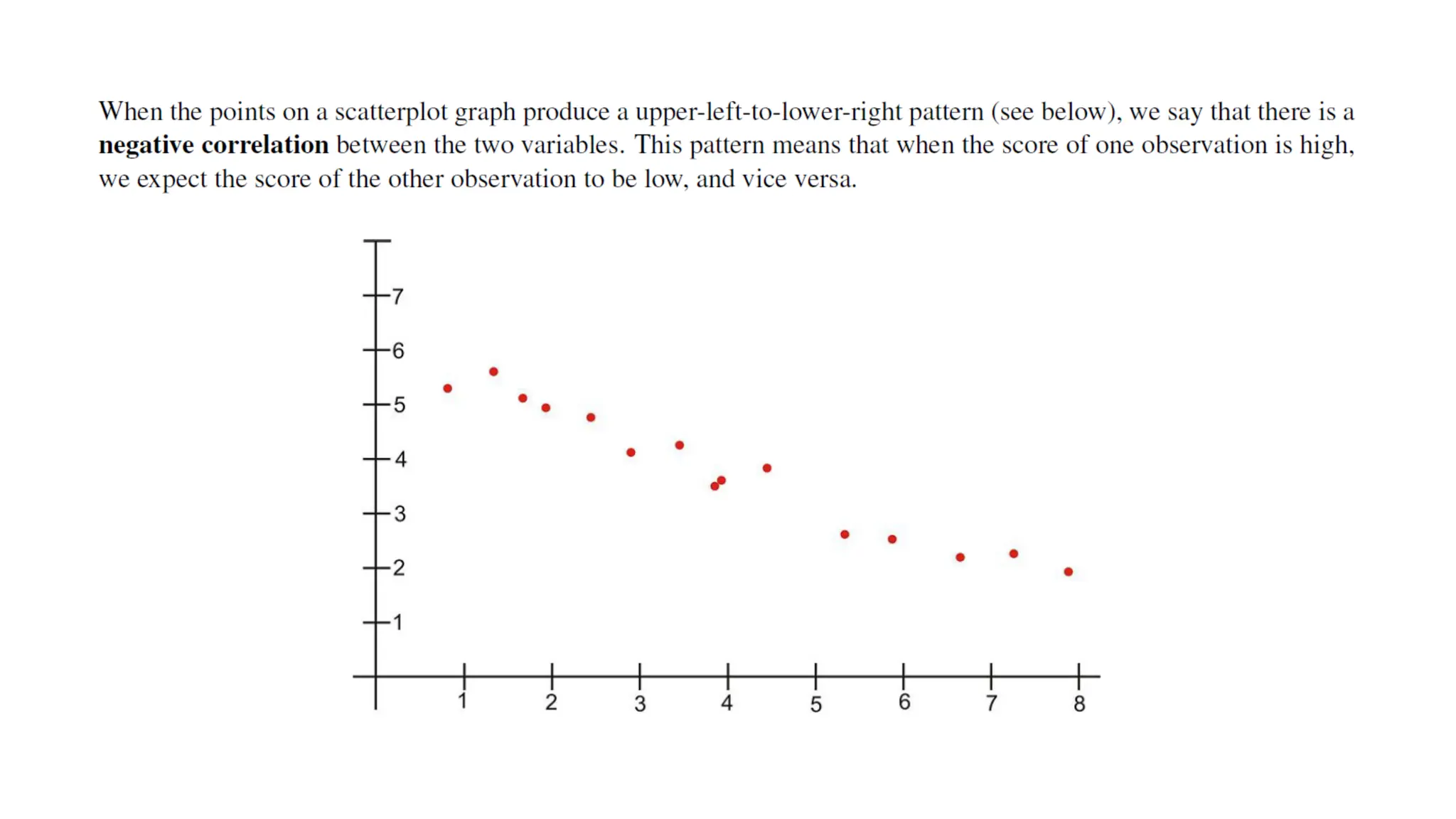

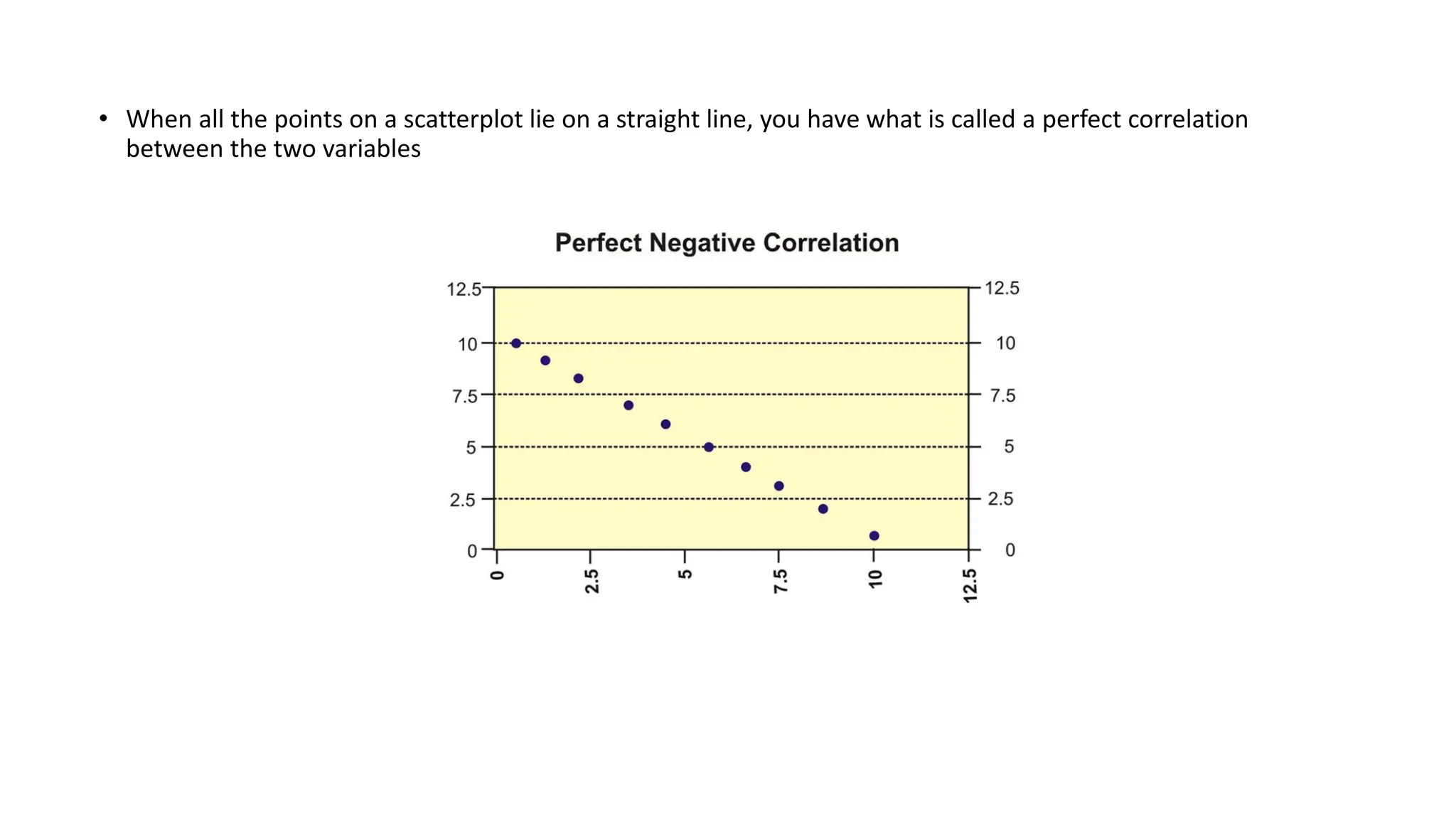

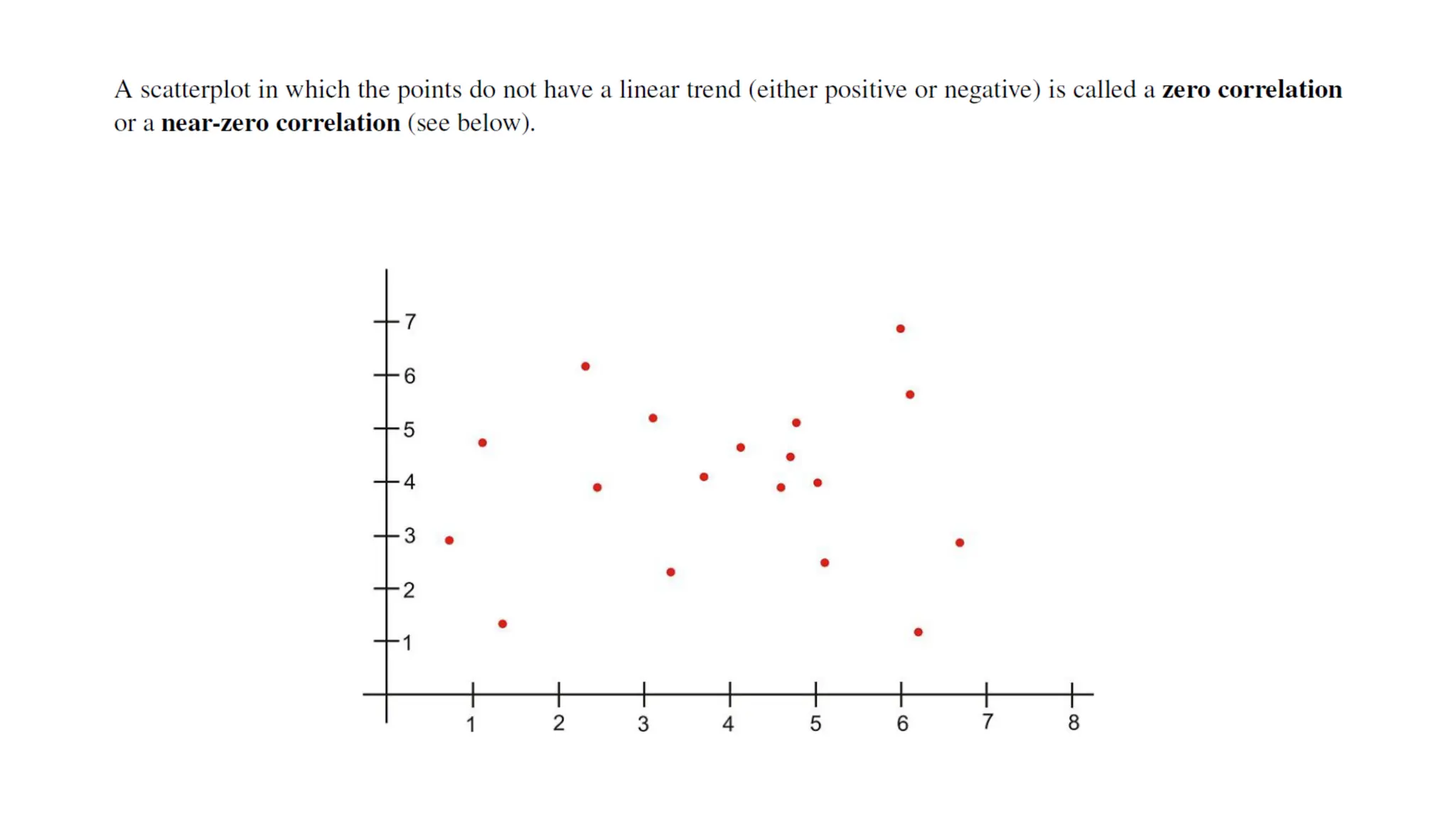

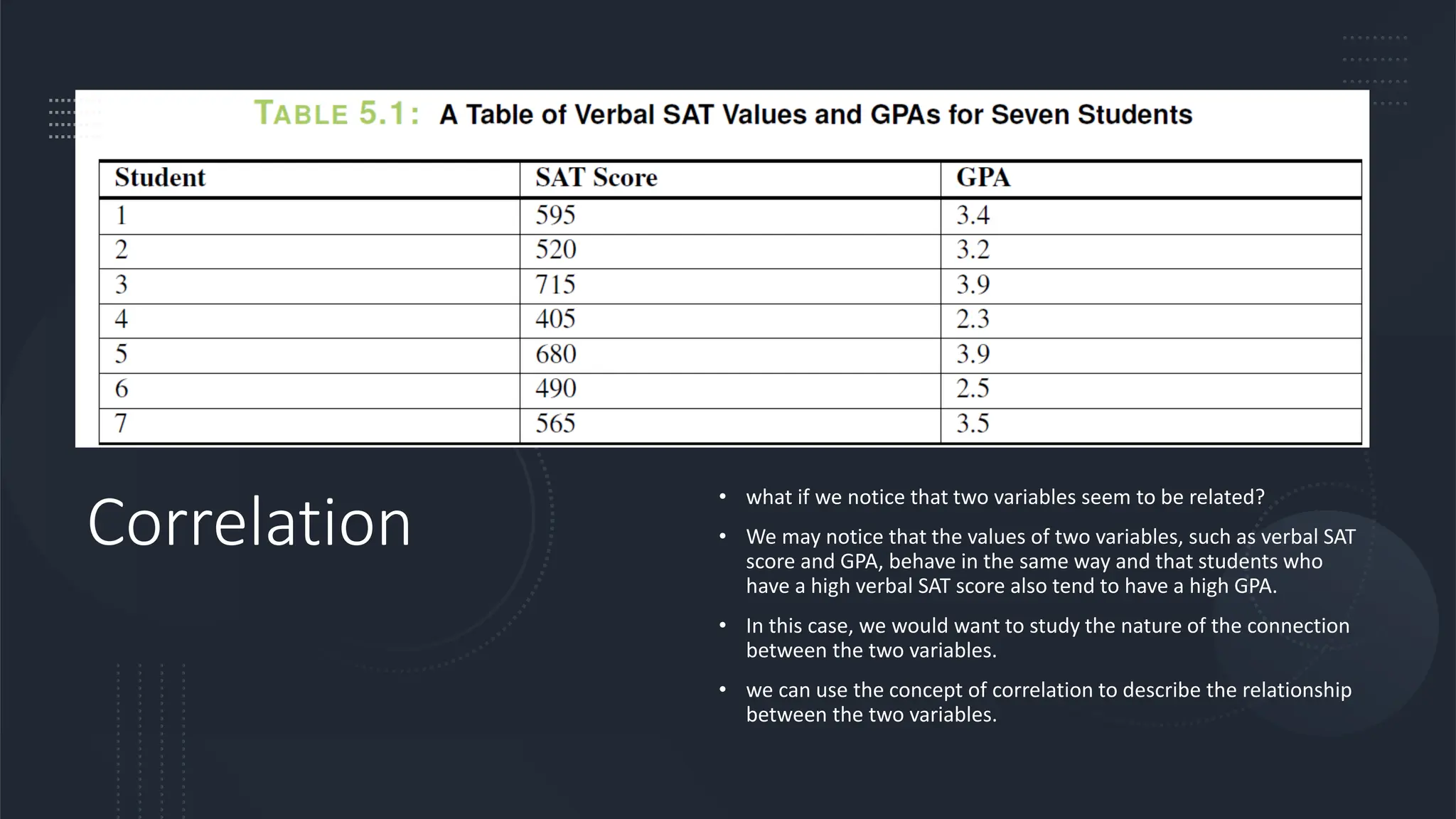

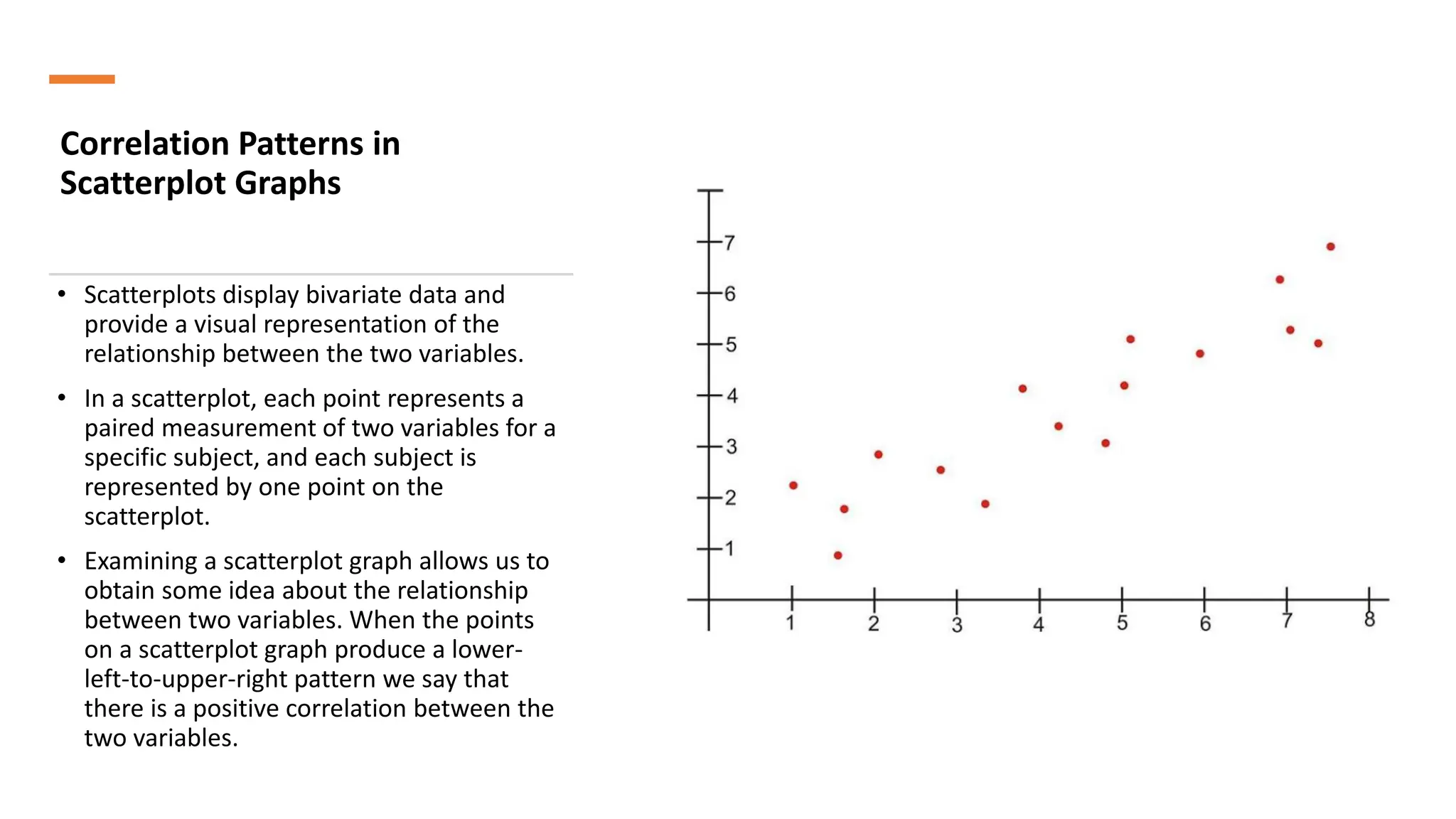

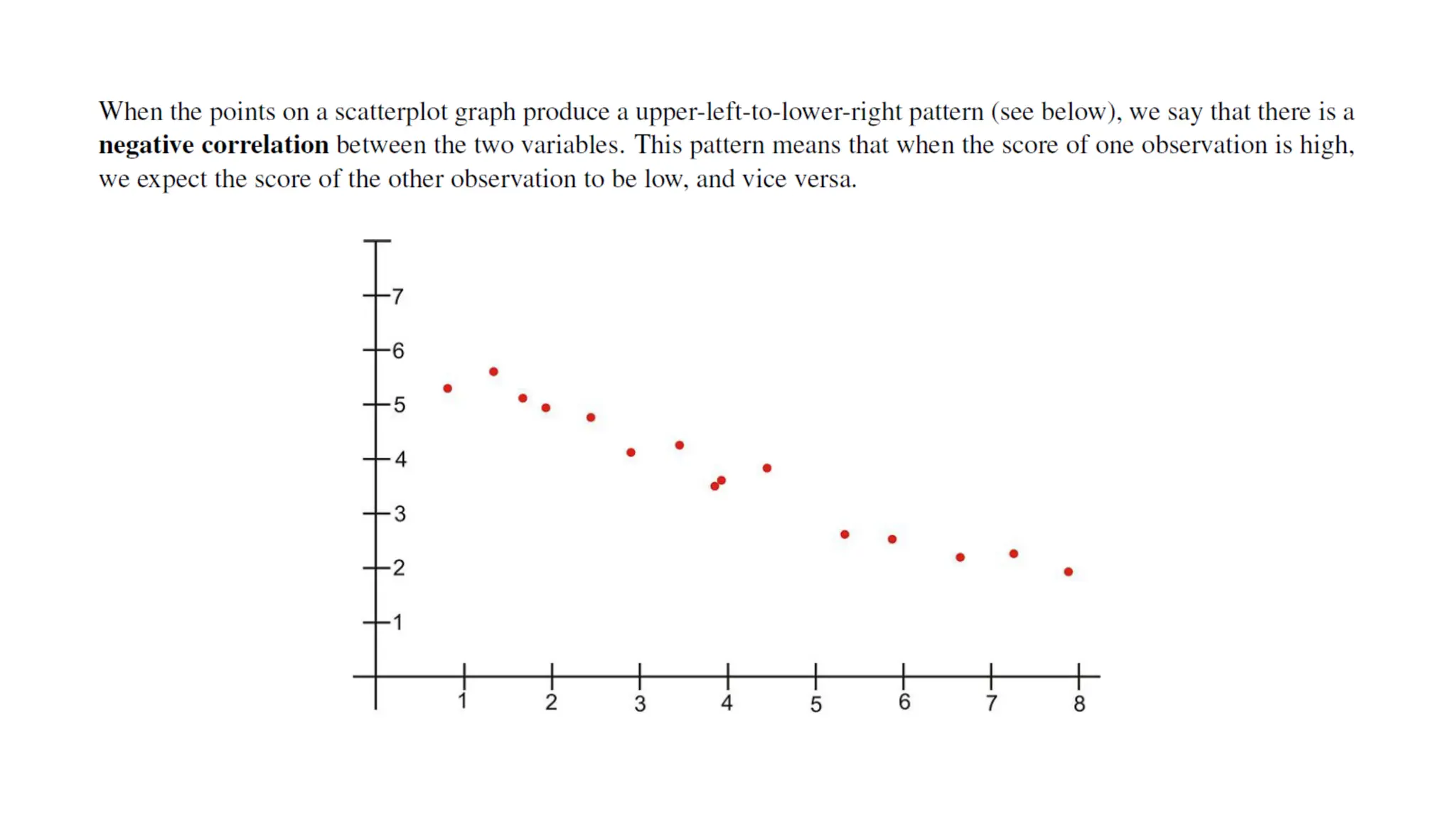

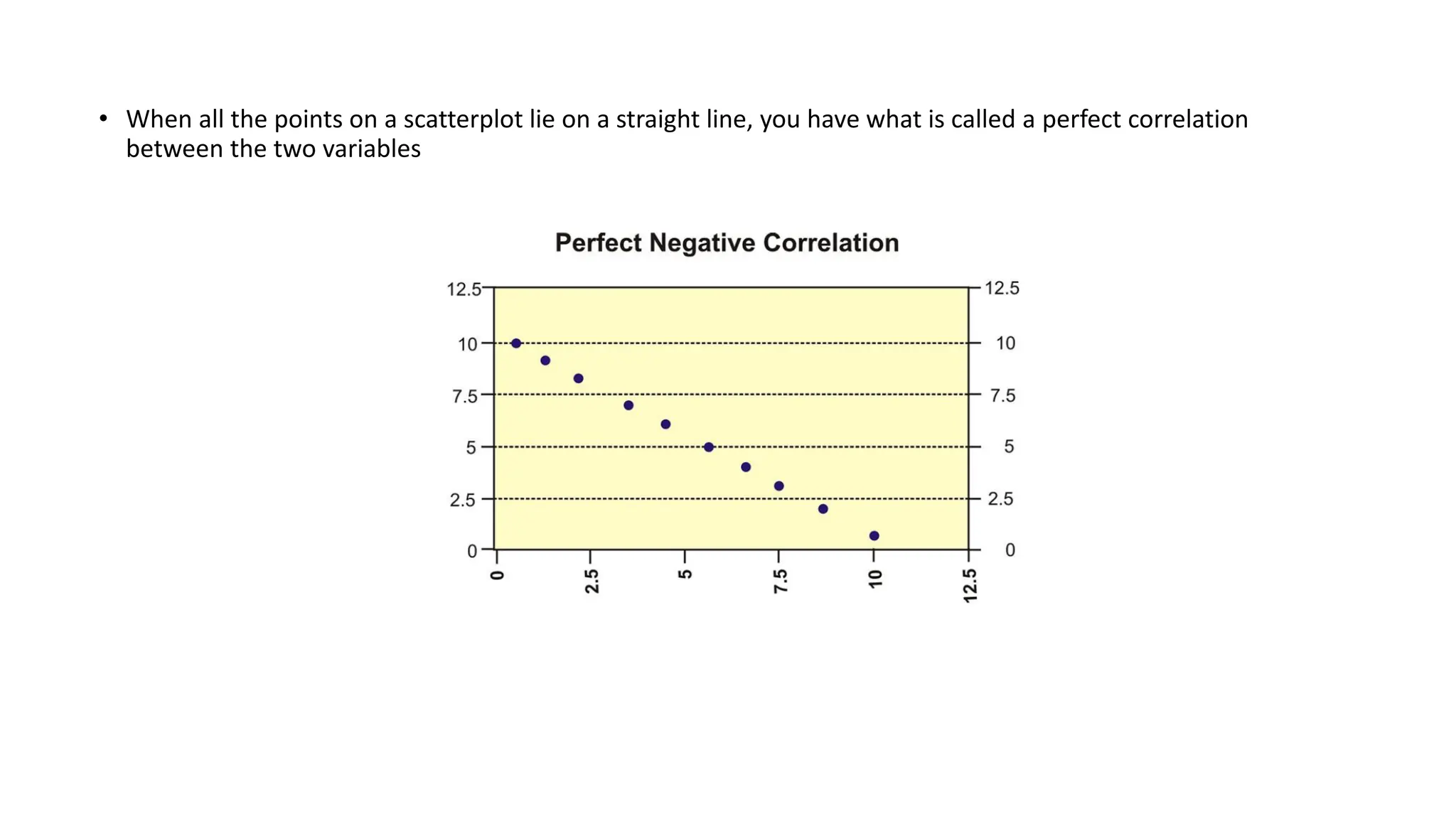

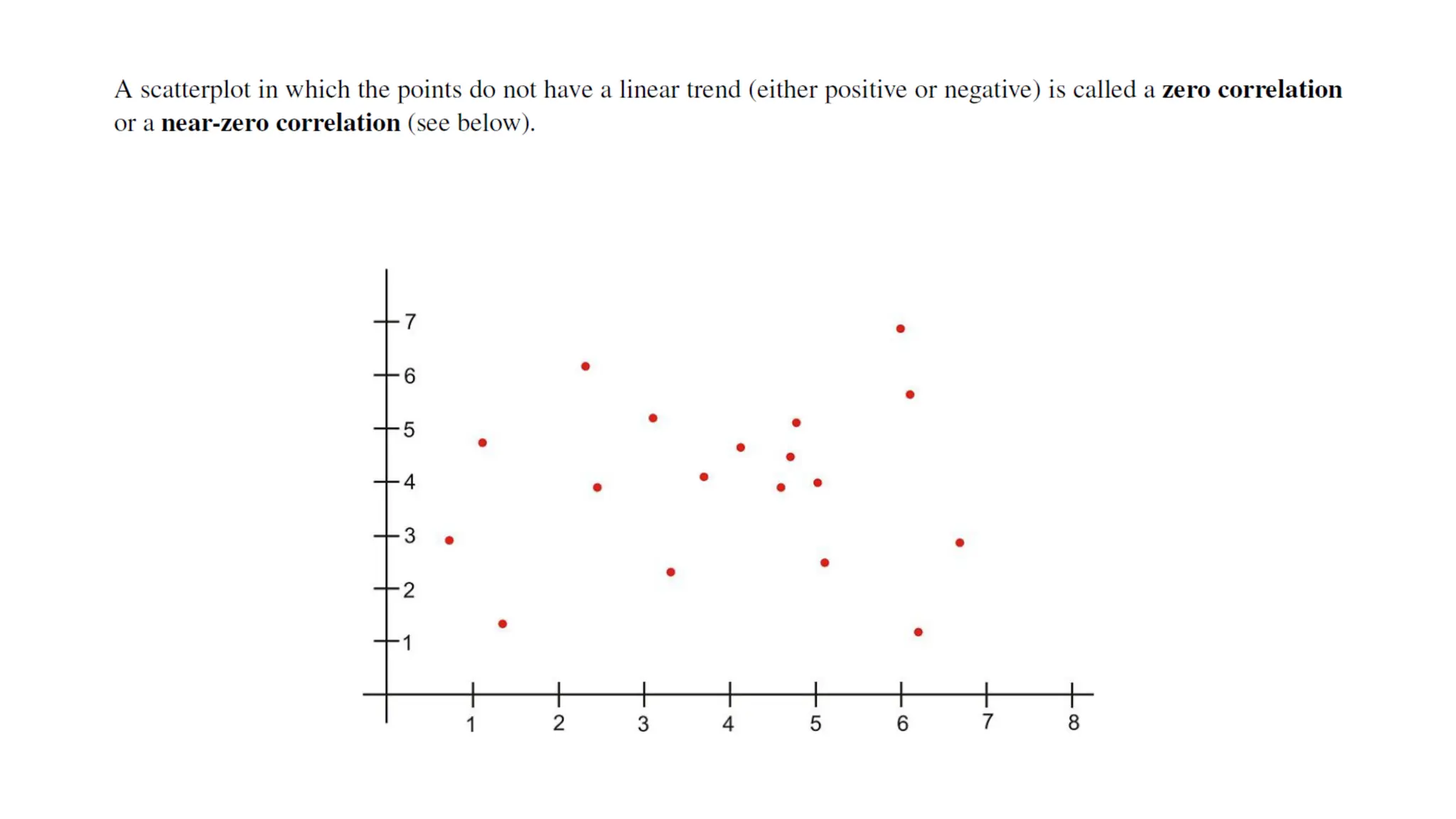

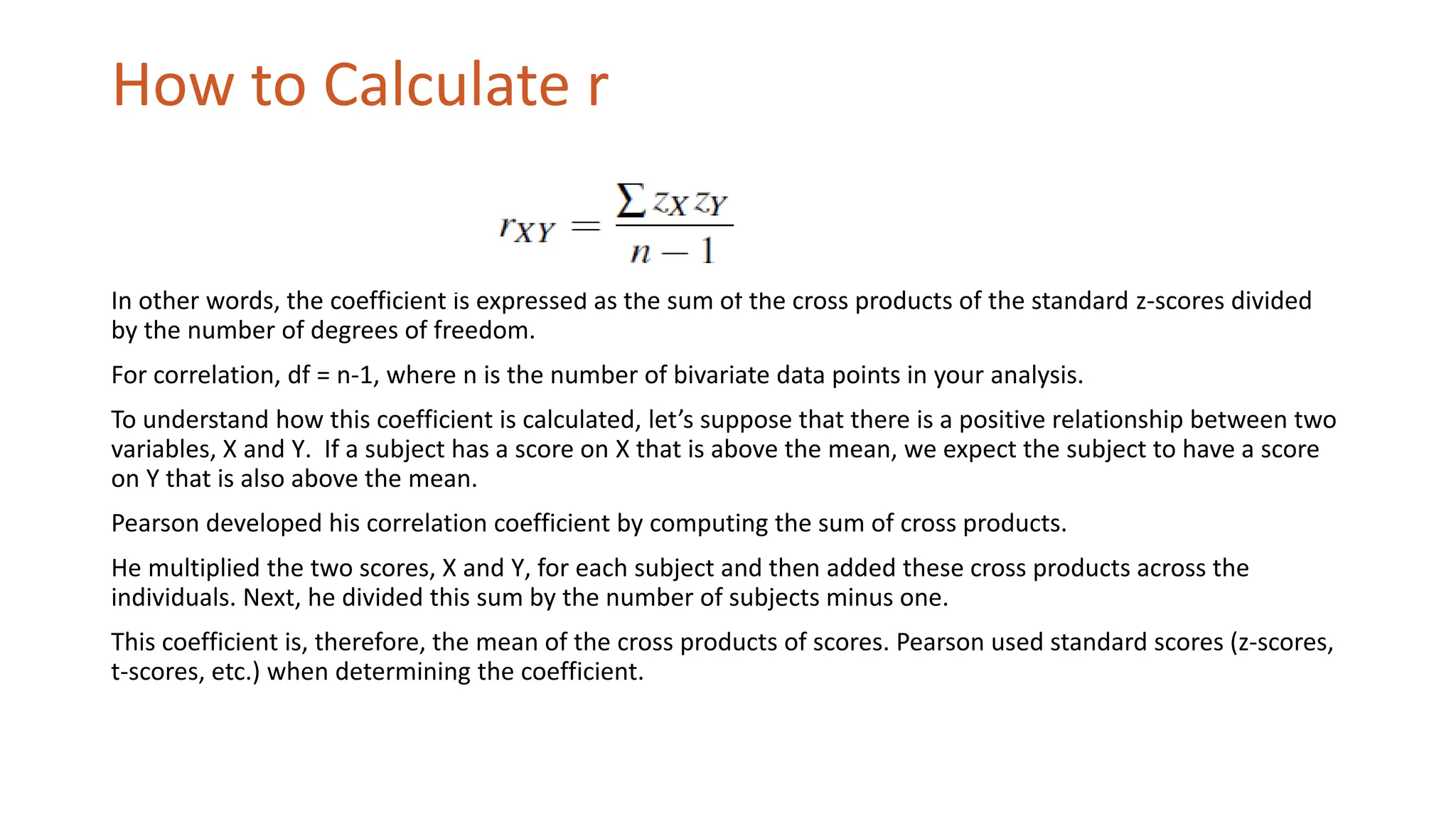

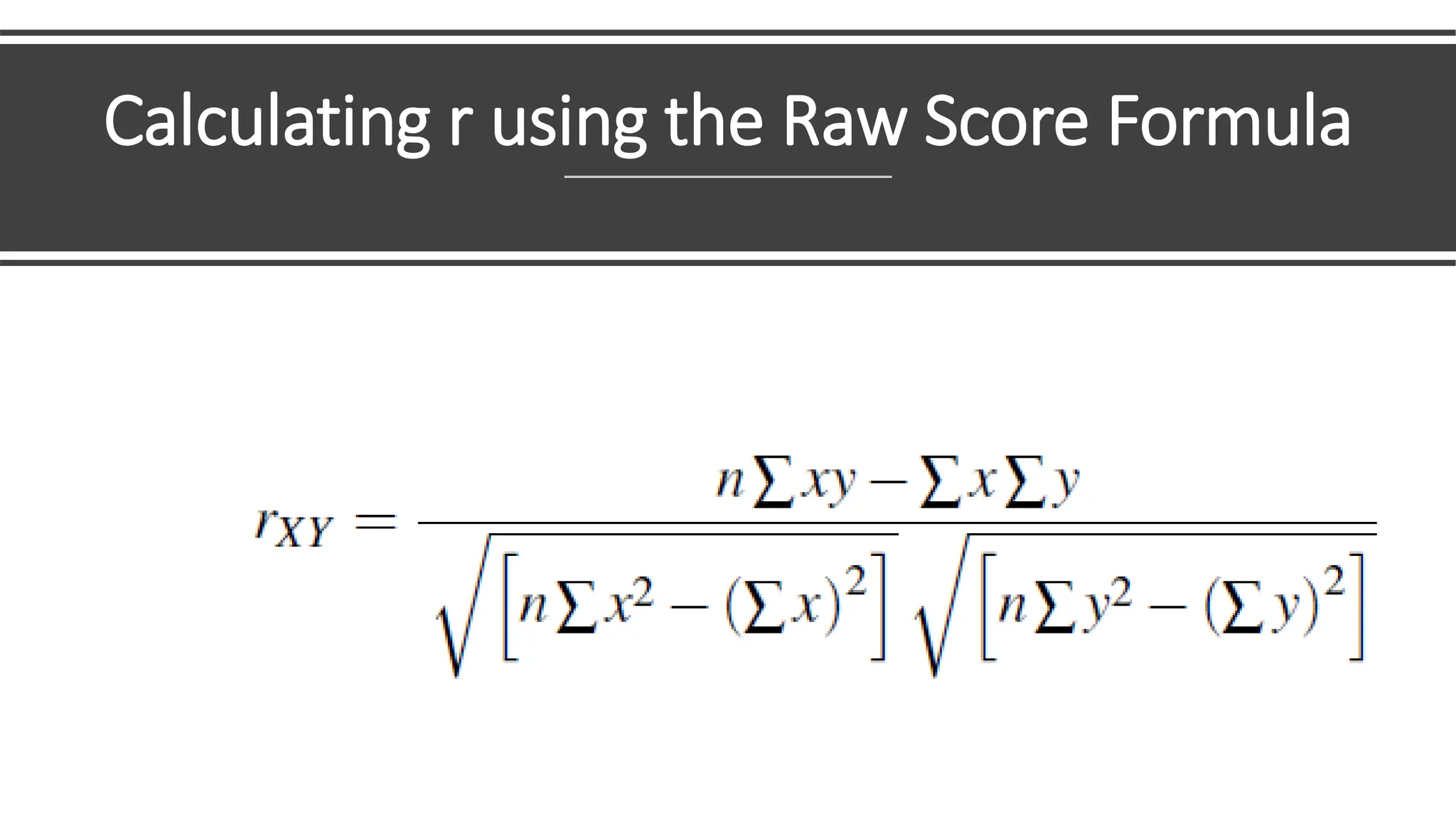

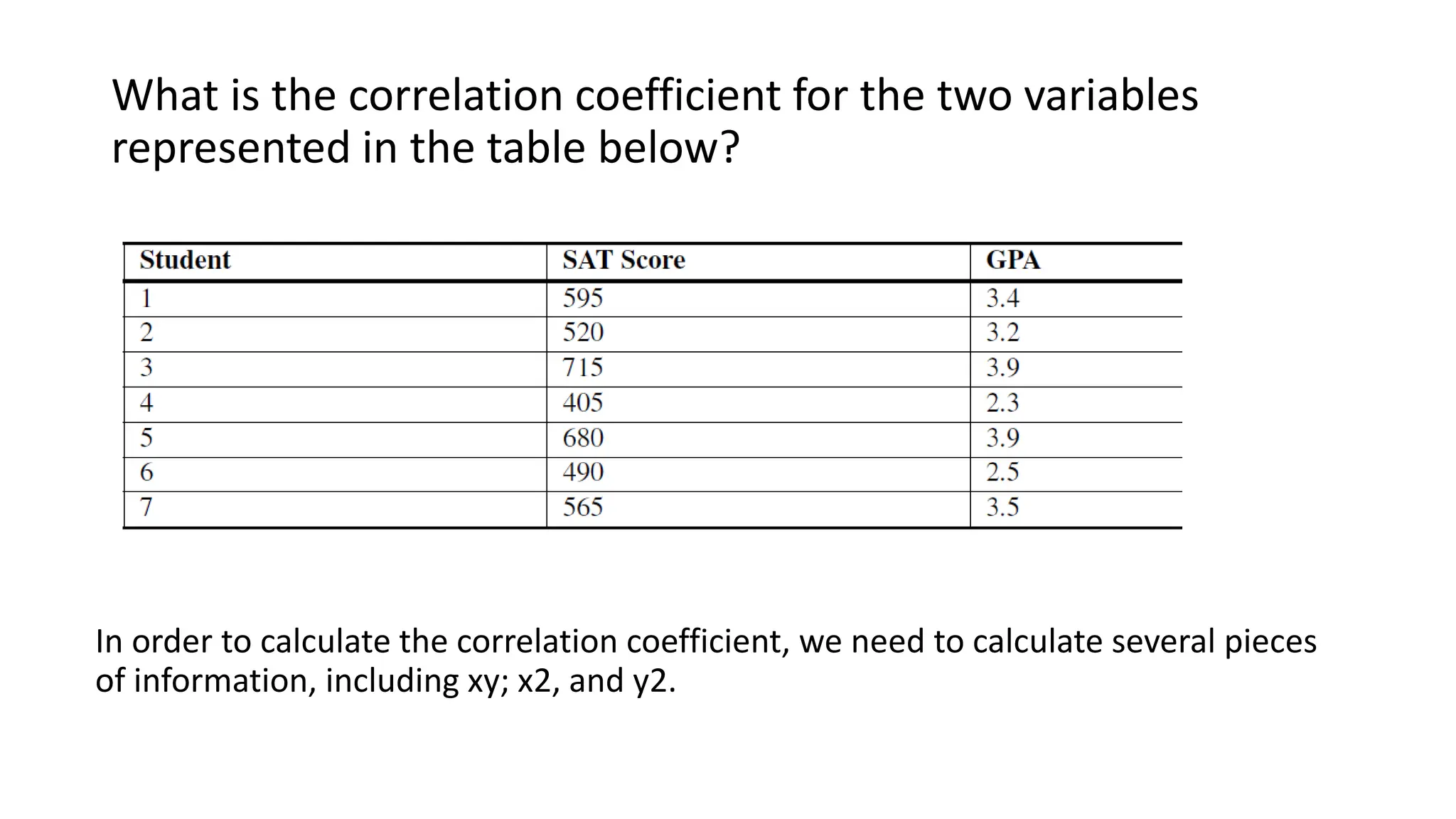

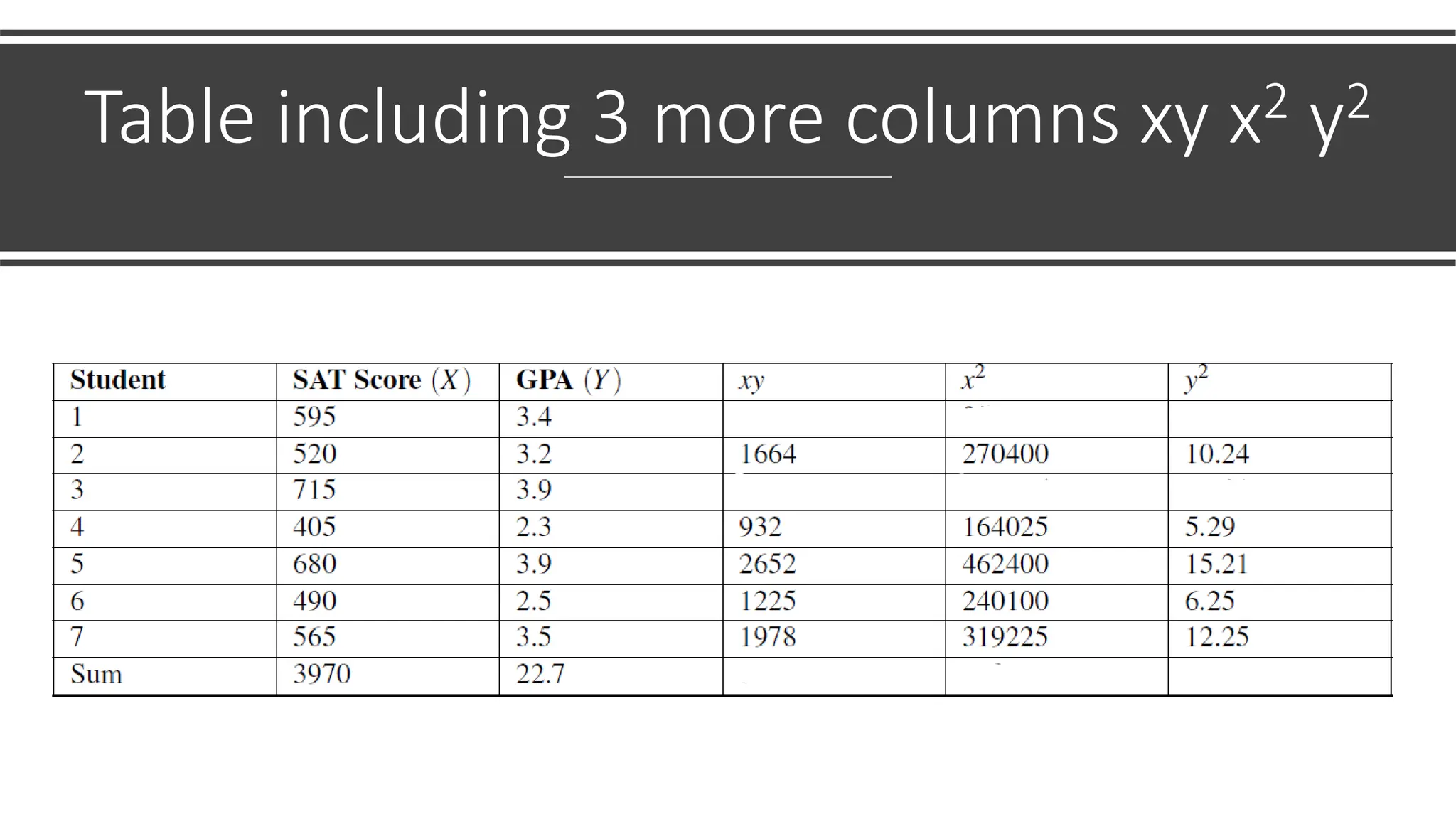

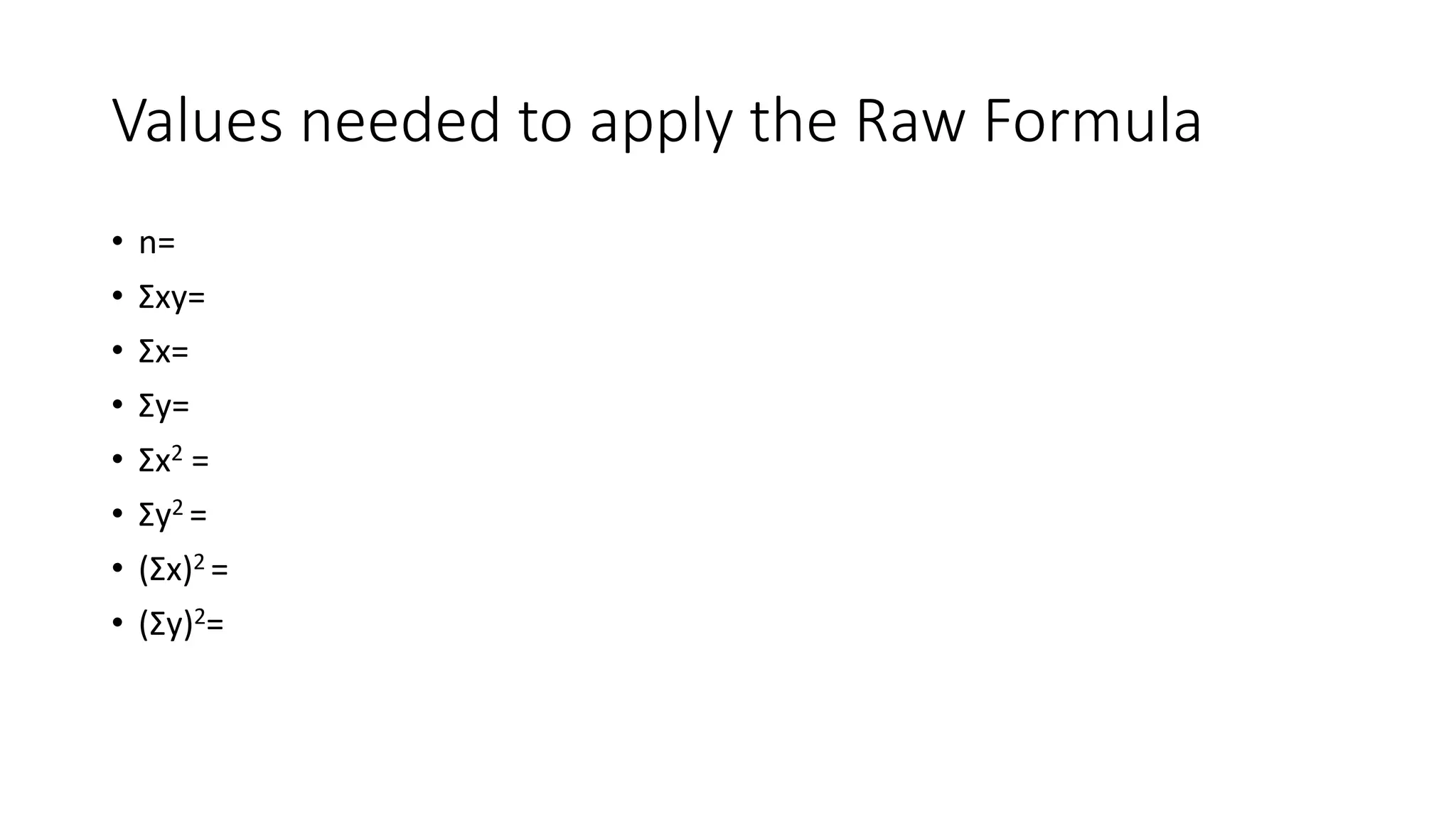

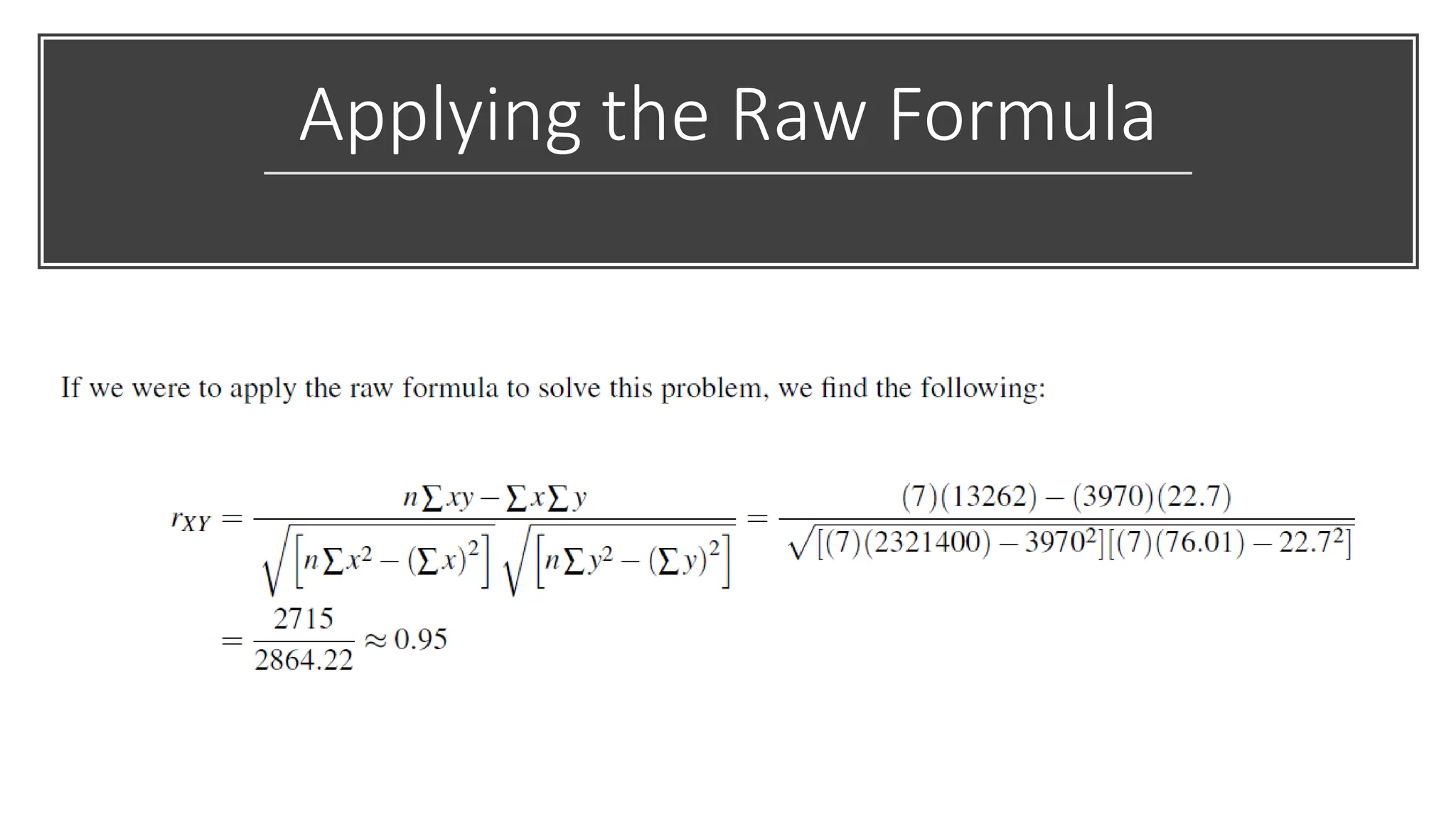

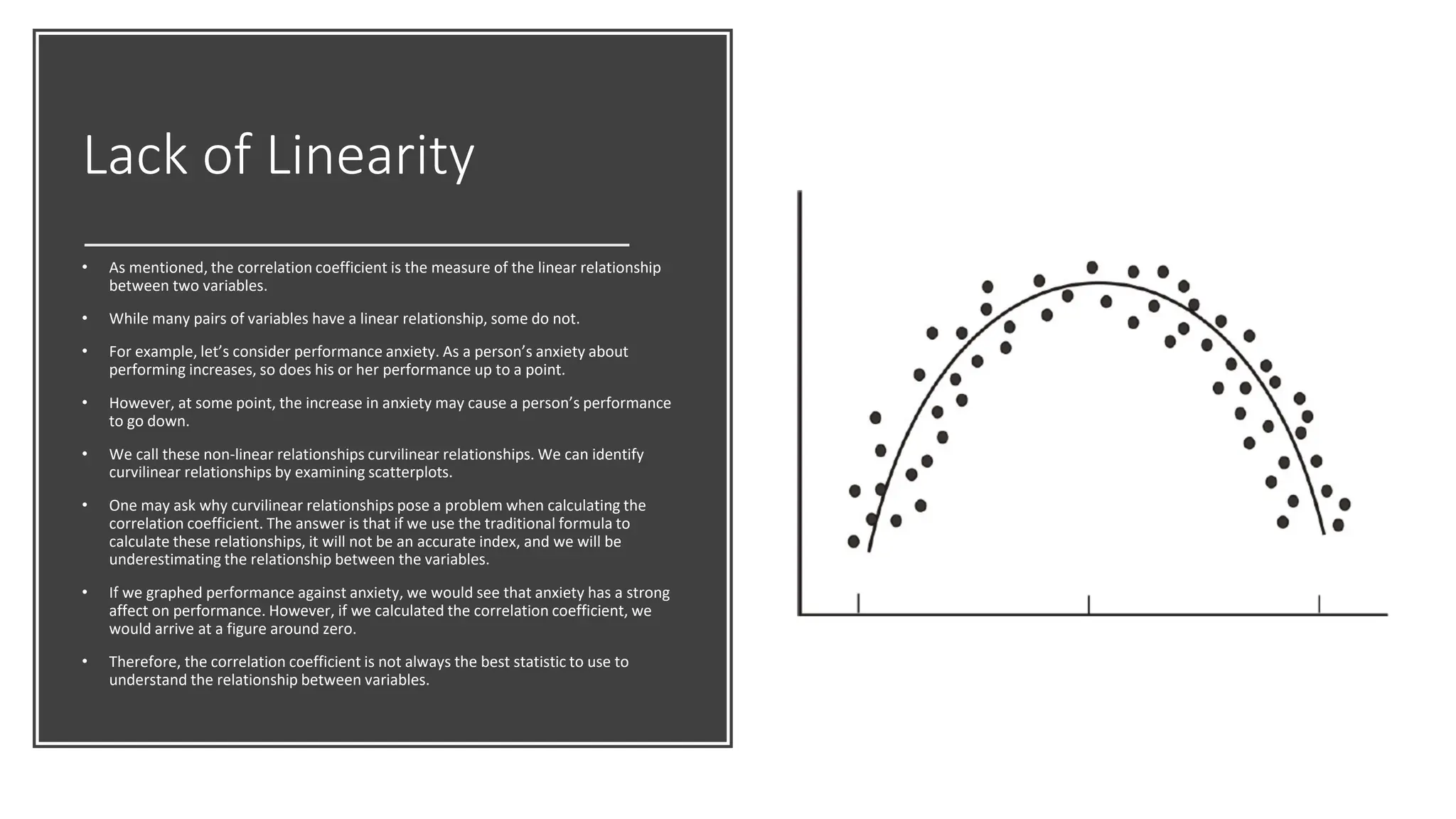

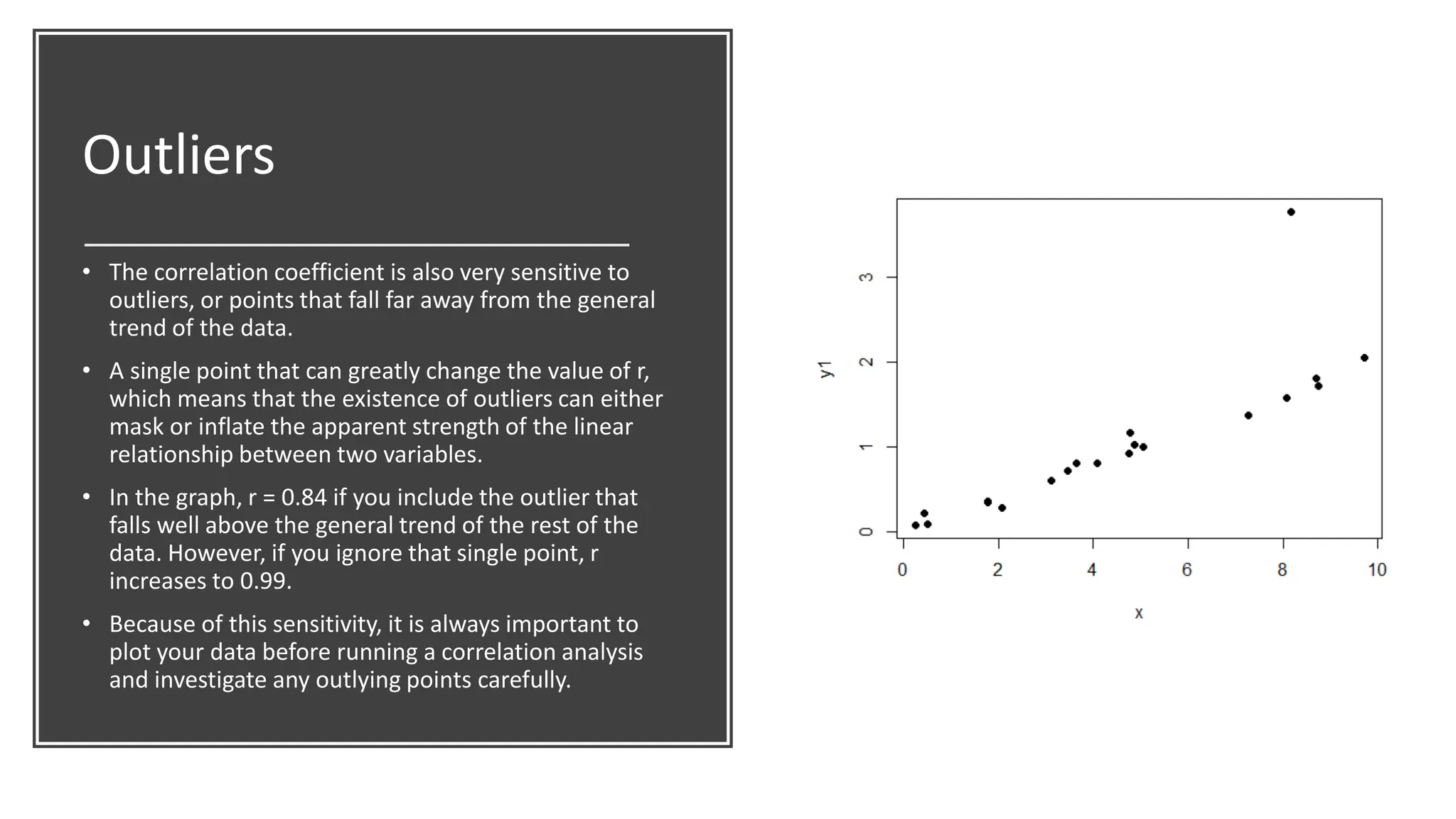

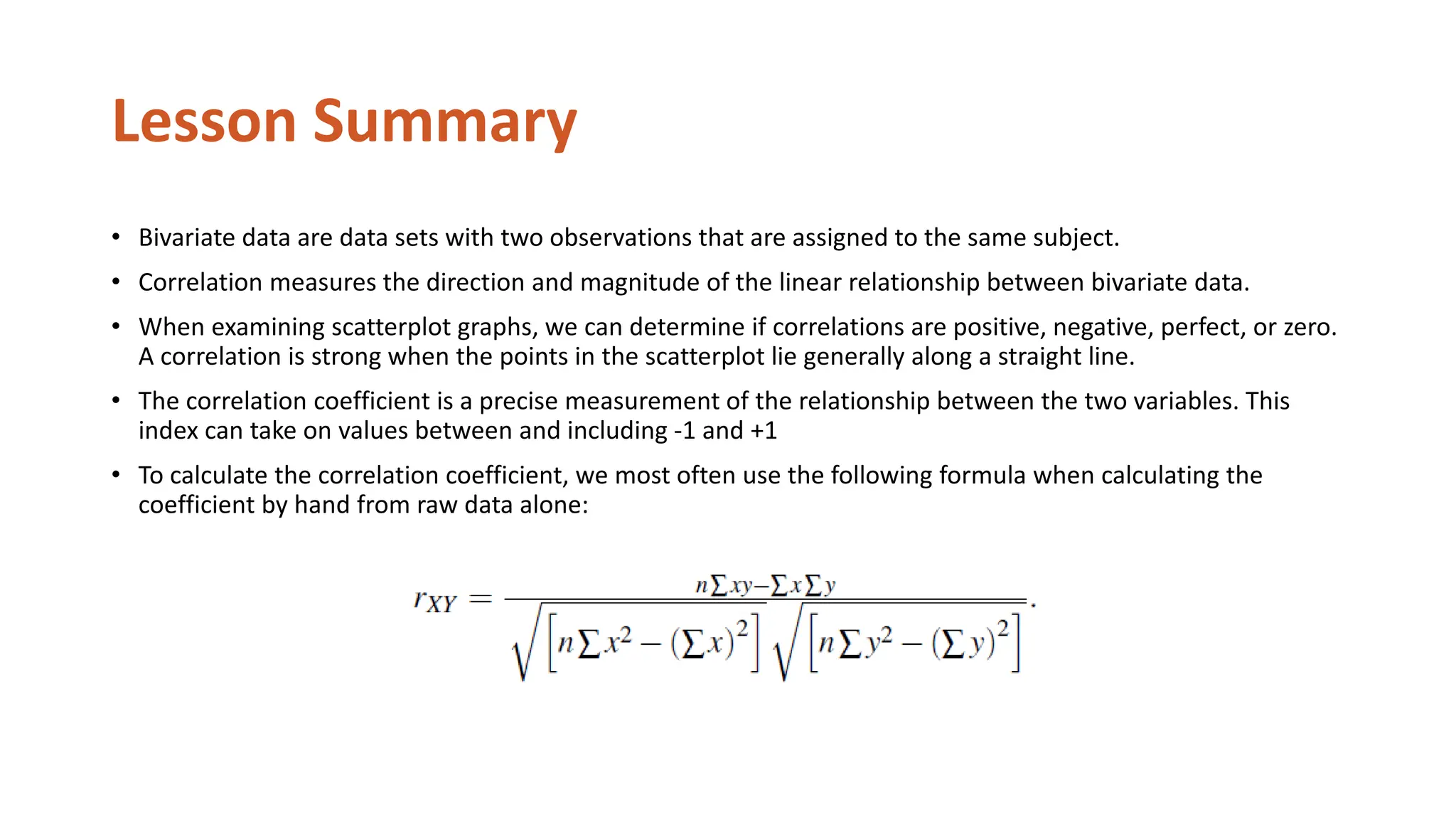

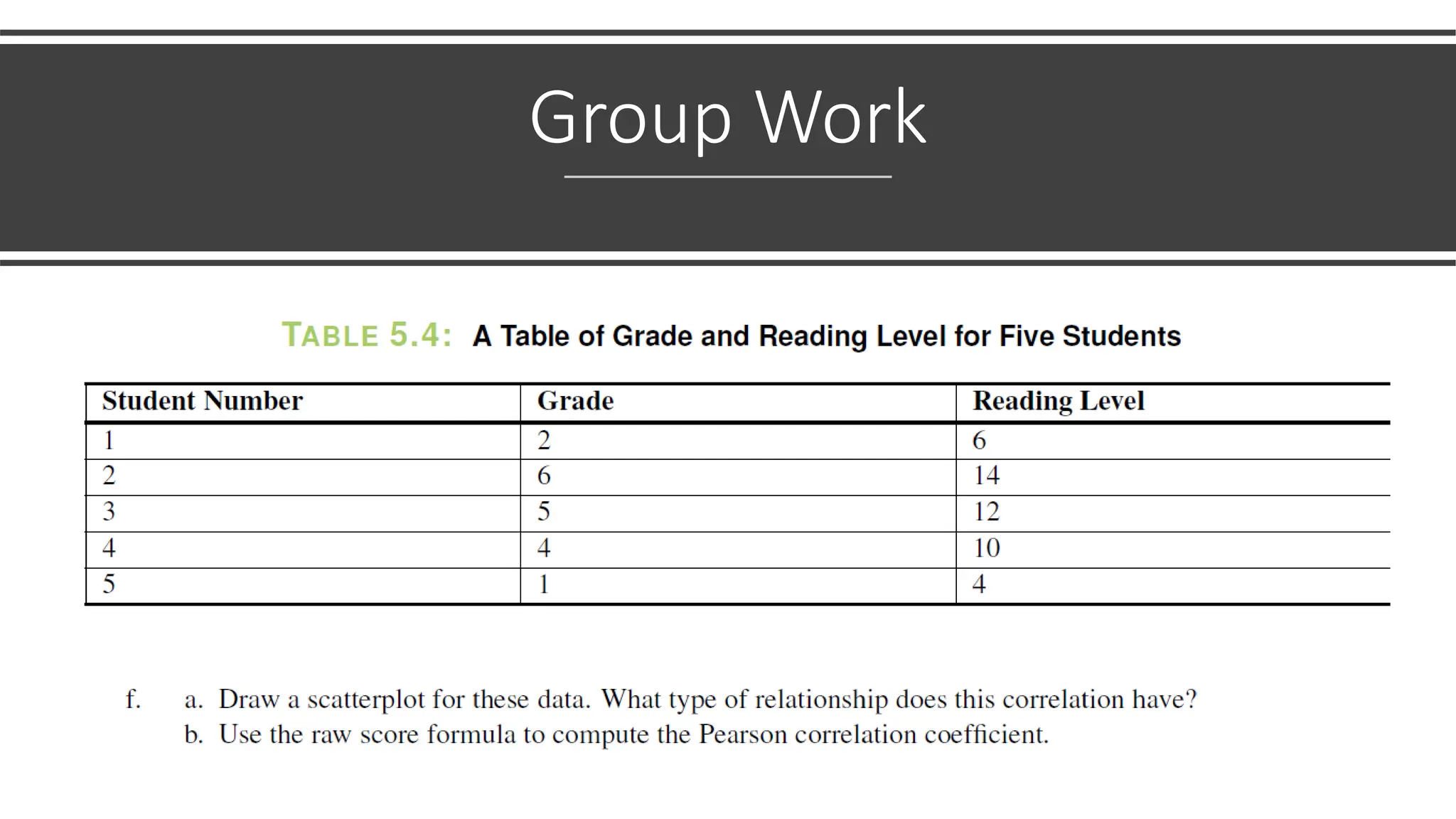

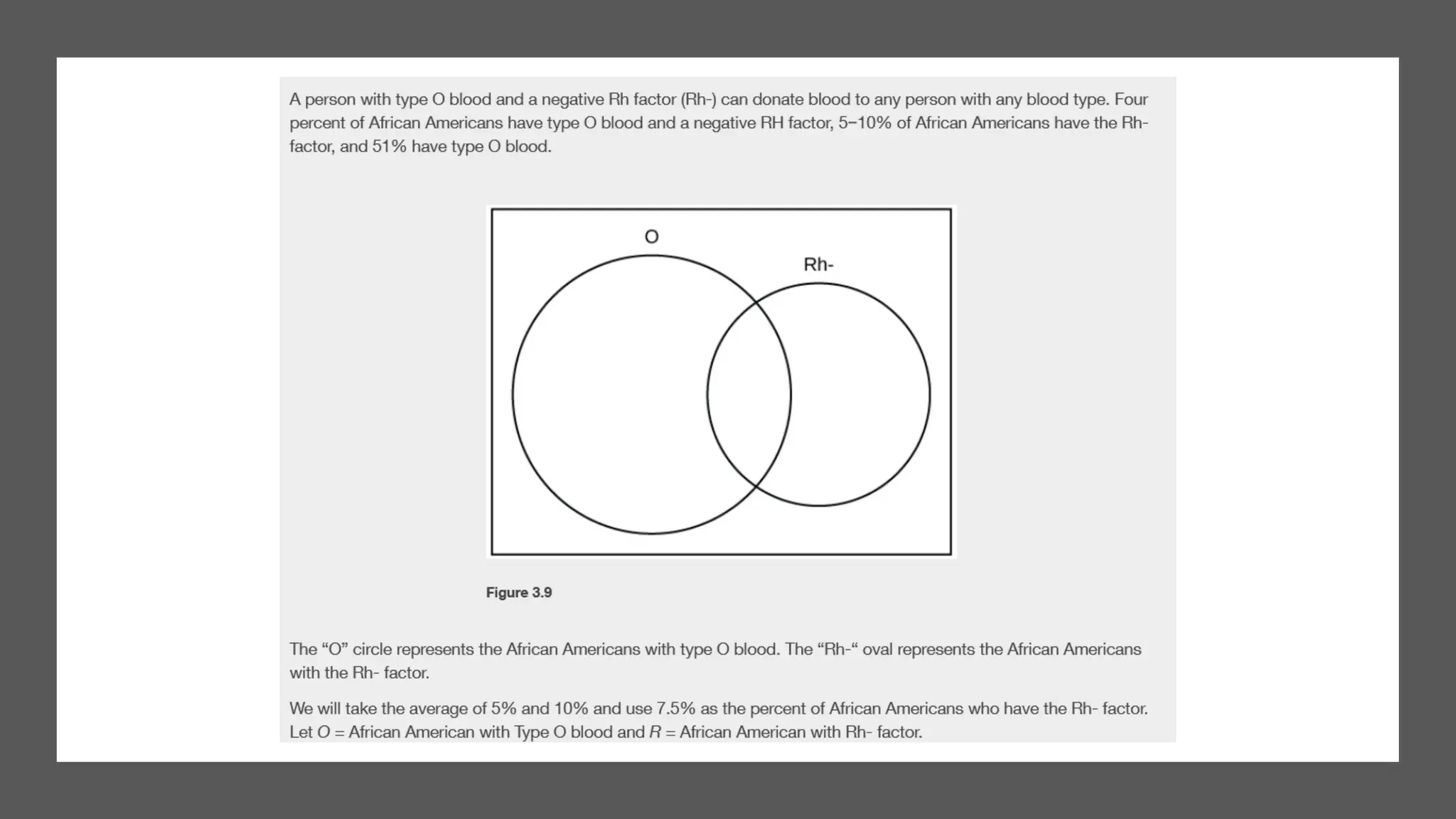

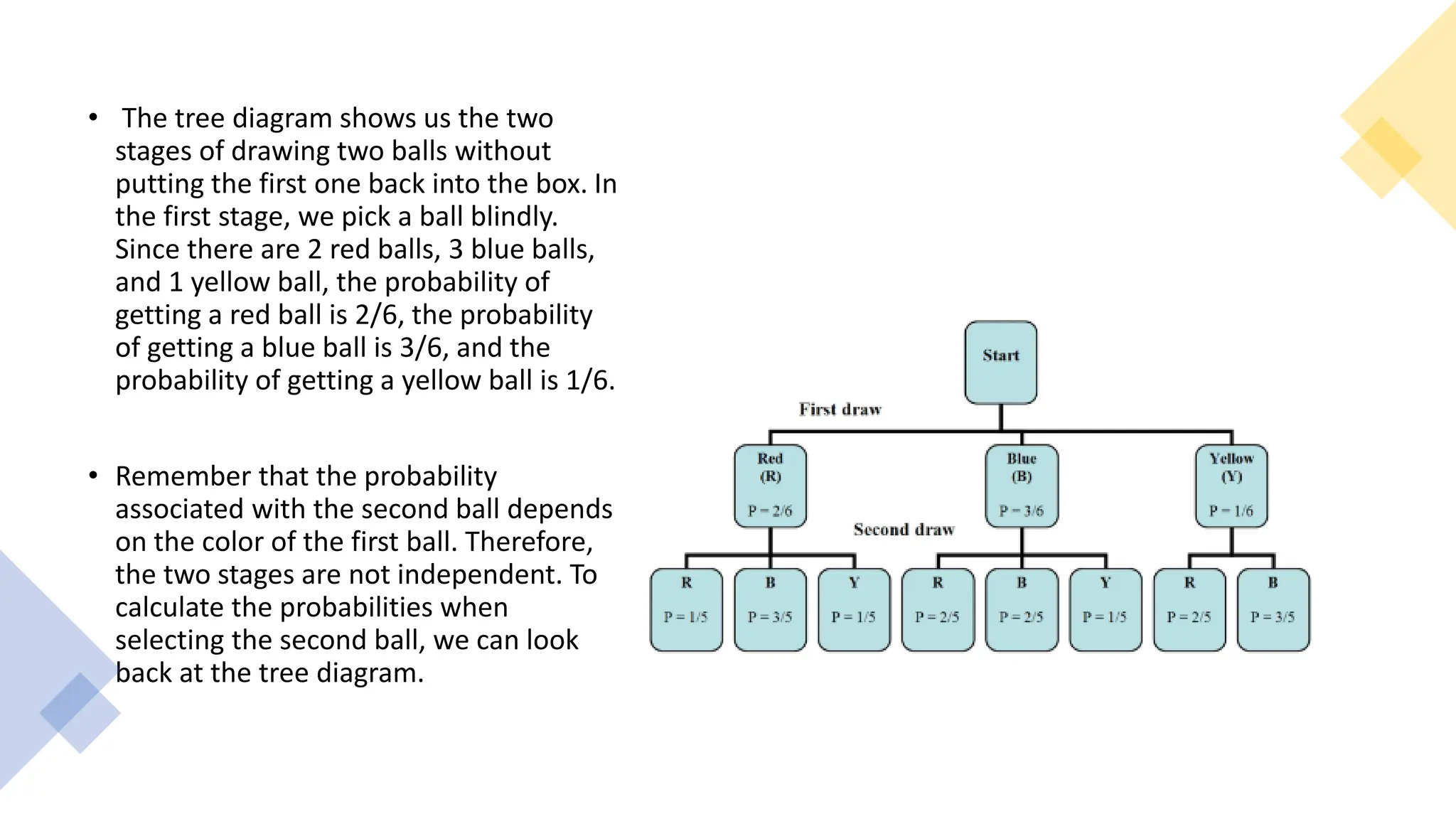

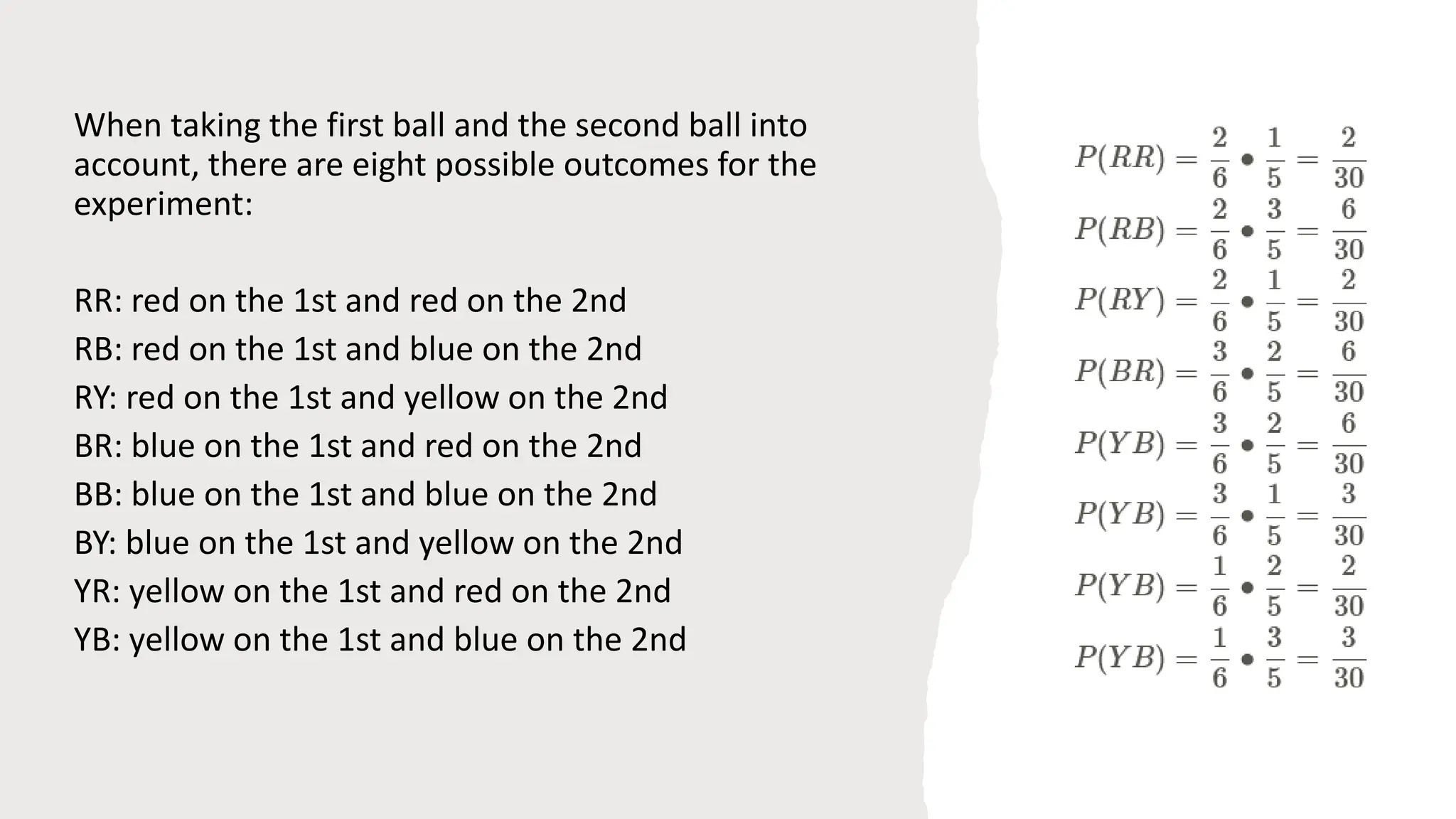

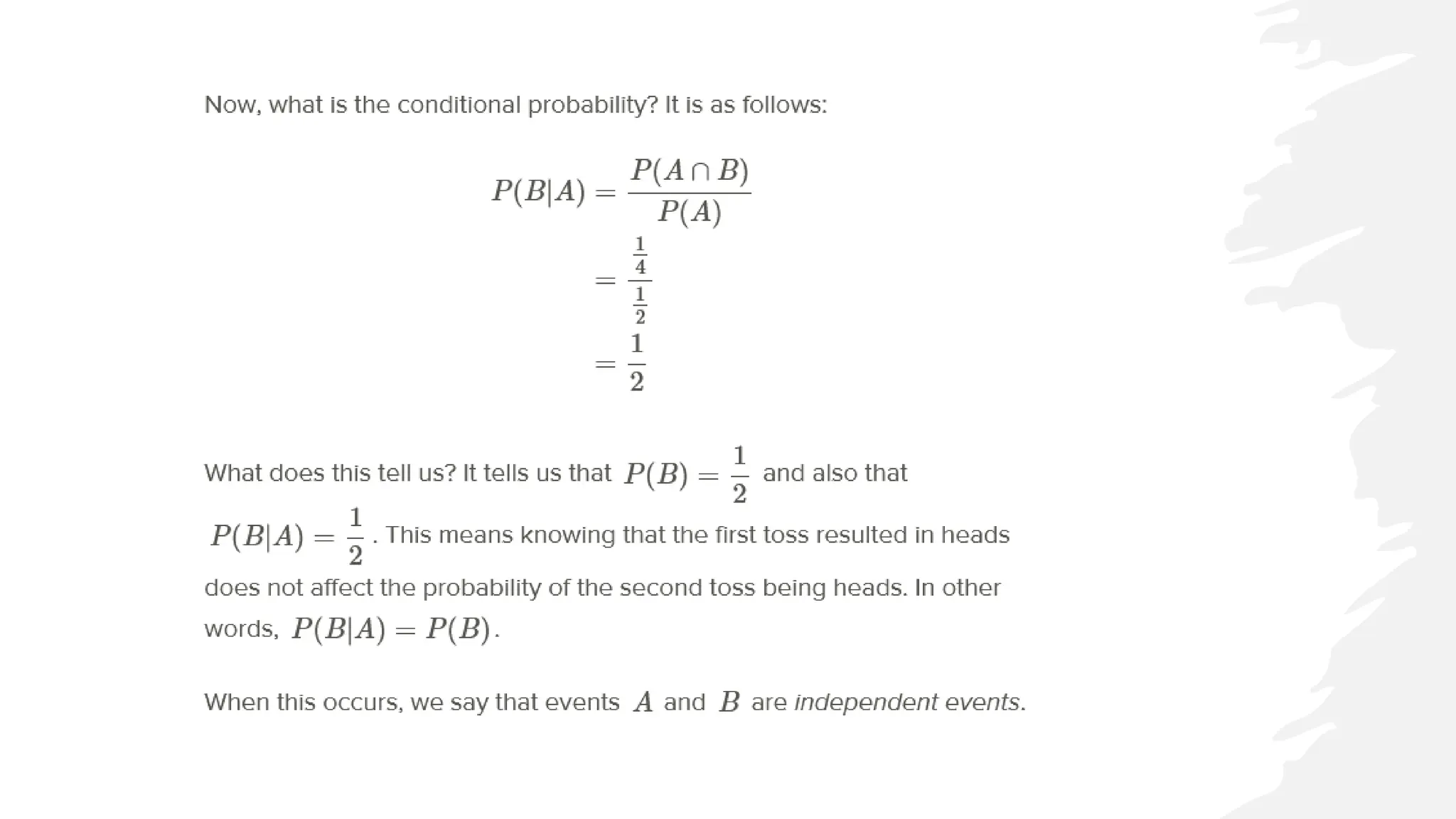

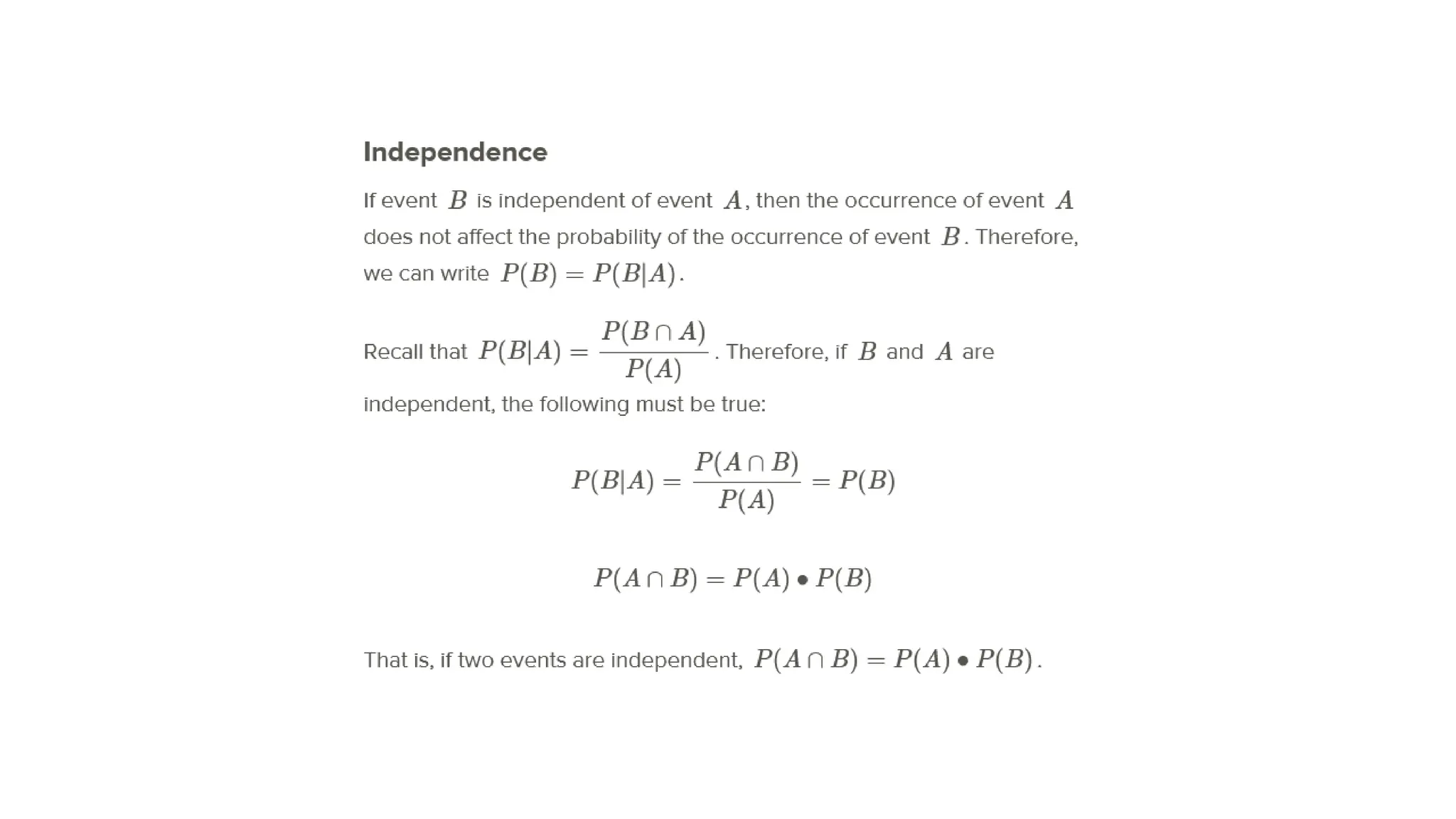

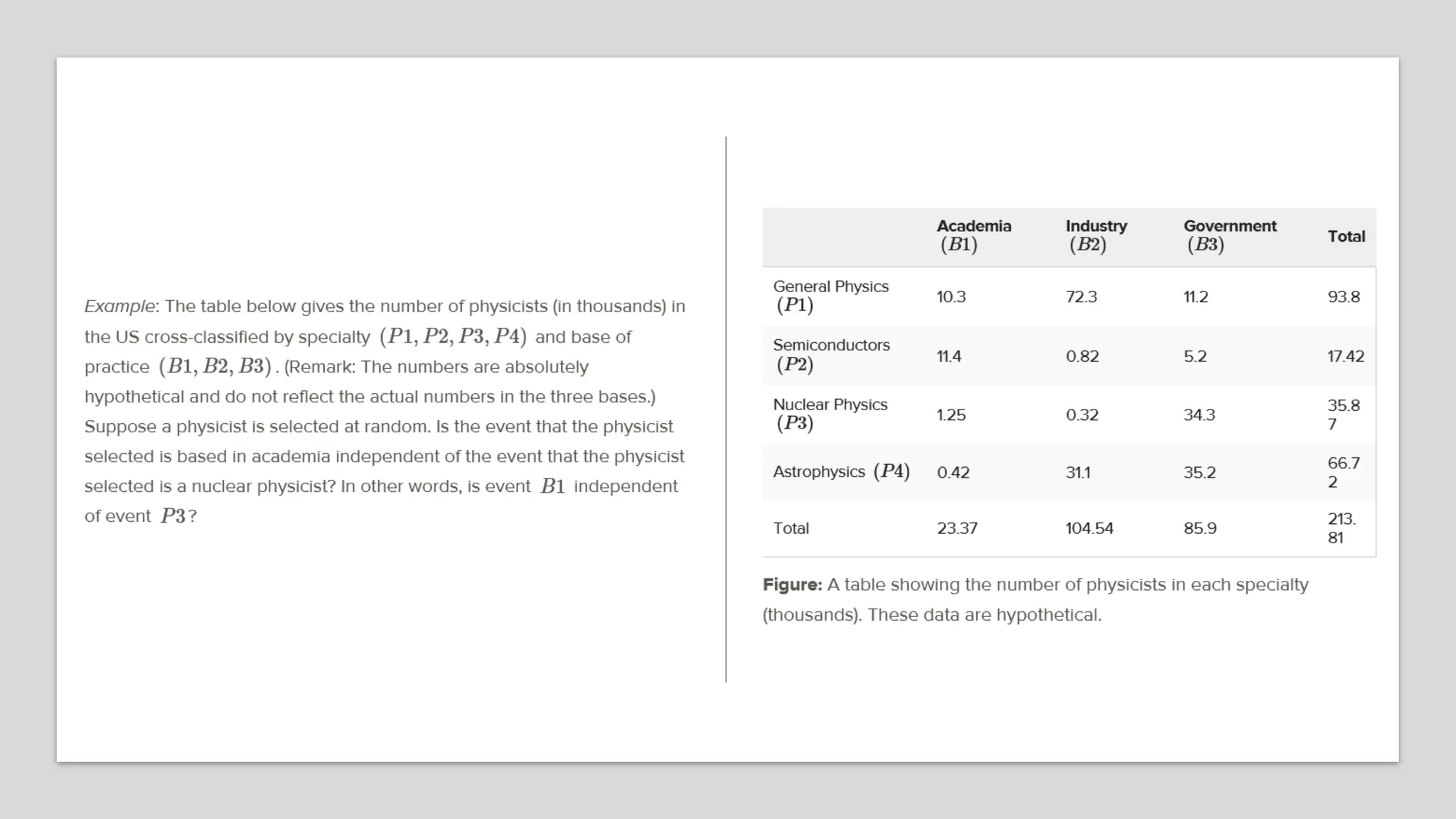

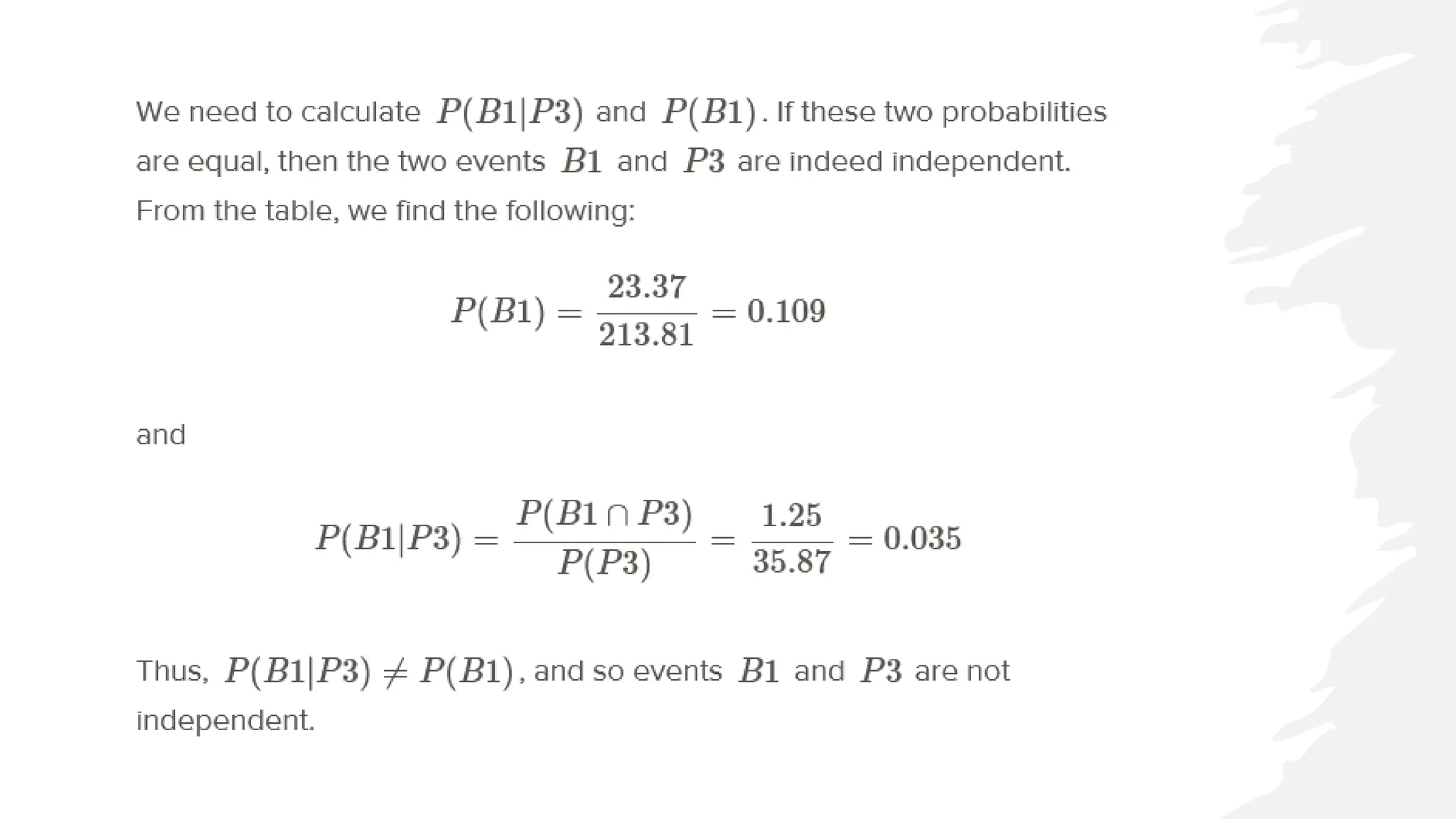

The document discusses bivariate data analysis, focusing on relationships between two quantitative variables through scatterplots and correlation coefficients. It highlights the characteristics of bivariate data, such as shape, direction, and strength, and provides examples of correlation in real-world contexts, including recycling rates and waste generation. Additionally, it explains how to calculate the Pearson correlation coefficient and its implications for understanding relationships between variables.