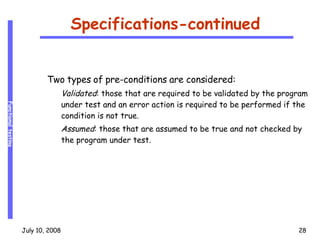

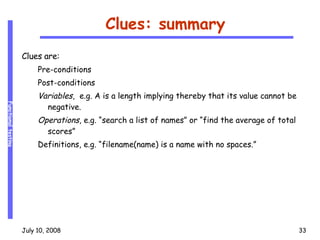

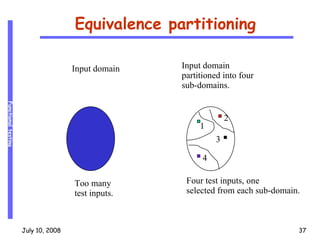

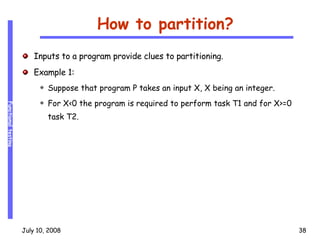

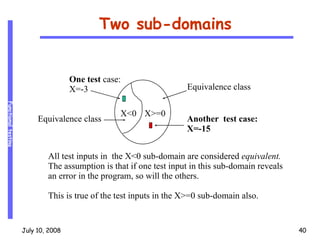

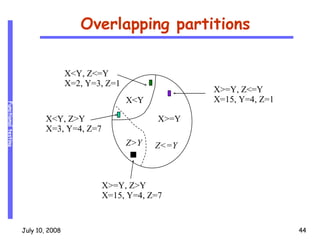

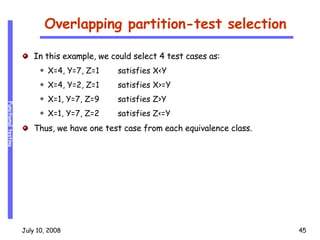

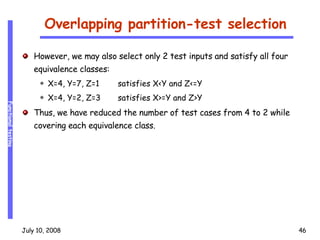

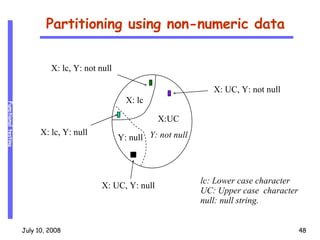

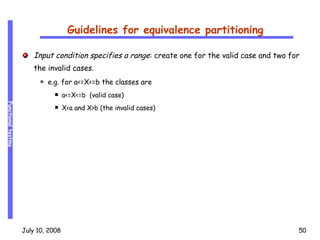

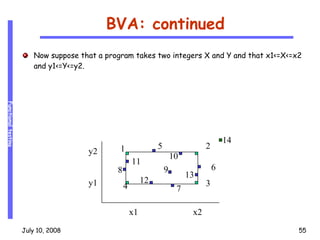

Functional testing generates test inputs based on a program's specifications. Testers derive clues from specifications, which inform test requirements and test specifications. Equivalence partitioning divides the input domain into equivalence classes, with the goal of selecting one test per class to cover all classes. Boundary value analysis focuses on boundary values as important test cases. Together, partitioning and boundary analysis aim to thoroughly test a program.

![Terminology Program - Sort Specification Input : p - array of n integers, n > 0 Output : q - array of n integers such that q[0] q[1] … q[n] Elements in q are a permutation of elements in p, which are unchanged Description of requirements of a program](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3btesting-1215672826236823-8/85/Testing-3-320.jpg)