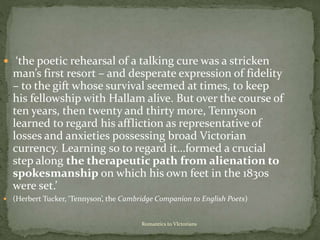

This document provides an overview of the Victorian poet Alfred Tennyson and his long poem In Memoriam A.H.H., which was written over 17 years in memory of his friend Arthur Hallam. It discusses how the poem grappled with new scientific ideas emerging in the Victorian era like the origins of the earth and humanity. While some critics saw the poem as finding satisfaction over time, others felt Tennyson's language evaded expectations and the possibility of resolution.

![ But thou art turn’d to something strange

And I have lost the links that bound

Thy changes, here upon the ground

No more partaker of thy change (40)

Tennyson develops ‘an interesting alternative to

Spiritualism … [by means of]… a long series of elegiac

lyrics in which the poet communes with his dead friend

[Hallam].’ (Daniel Brown,’Victorian Poetry and Science’ Cambridge Companion to

Victorian Poetry)

Romantics to VIctorians](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tennysonim-170901095707/85/Tennyson-In-Memoriam-10-320.jpg)

![ Rupture with ‘Natural Theology’: ‘We have but faith,

we cannot know/ For knowledge is of things we see’ (I

M prologue)

Although perceived as an heir to the great Romantic

poets such as Wordsworth, Tennyson was acutely

aware of new scientific discoveries. He was according

to his friend and contemporary, scientist T.H. Huxley,

‘the first poet since Lucretius [a Classical Roman

writer on nature] who has understood the drift of

science.’

Romantics to VIctorians](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tennysonim-170901095707/85/Tennyson-In-Memoriam-13-320.jpg)