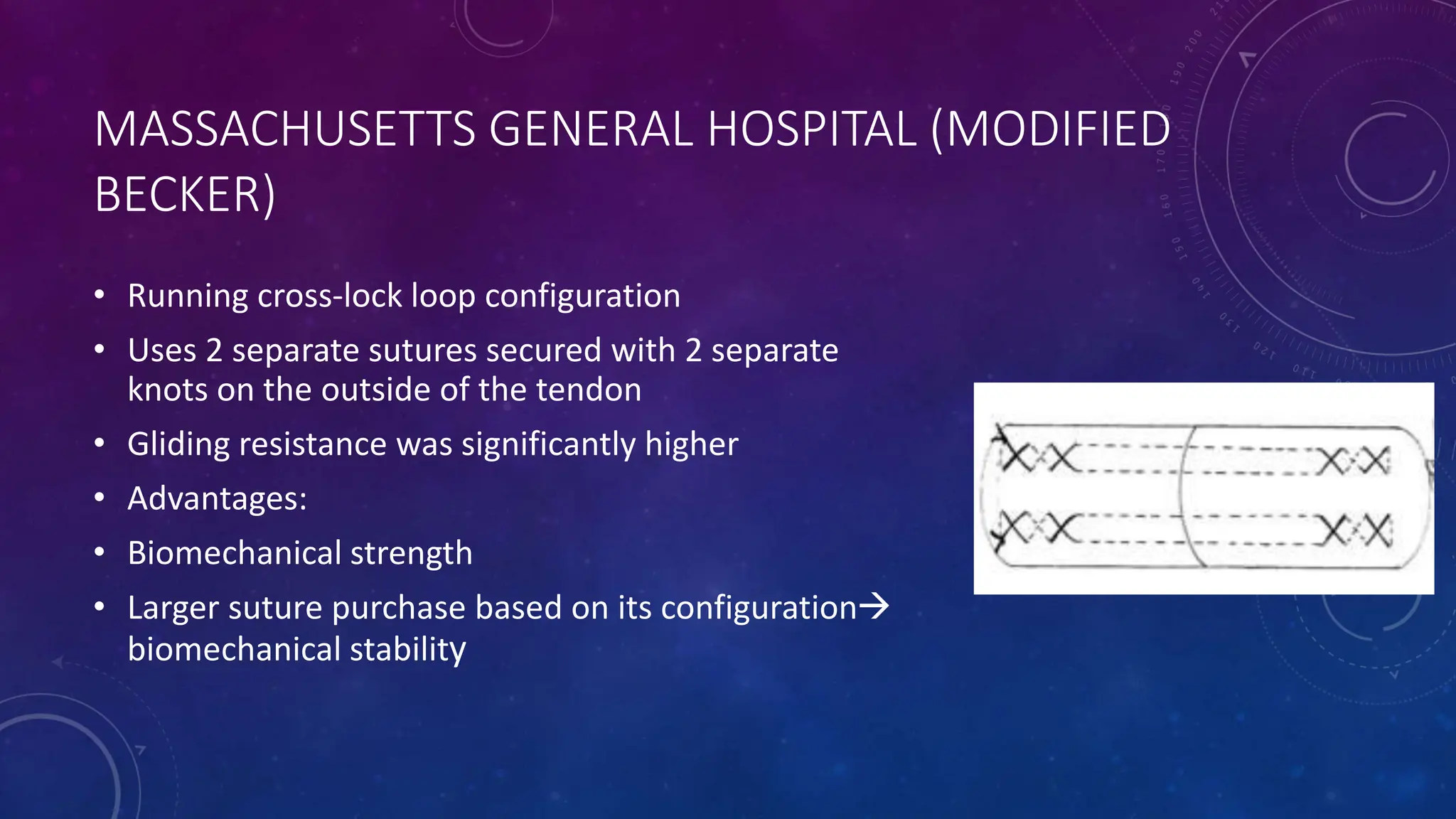

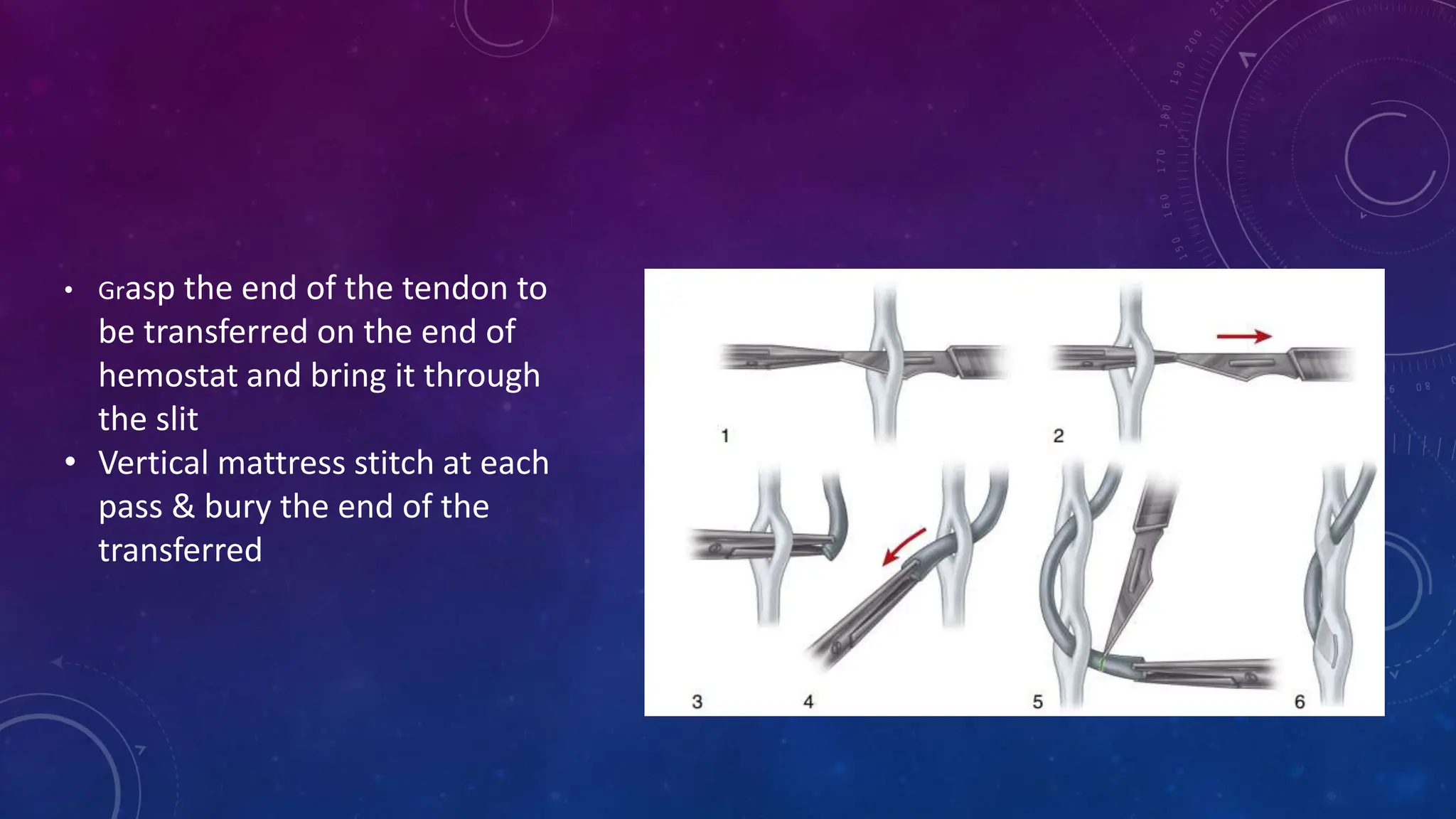

The document discusses various tendon repair techniques, emphasizing the importance of approximating tendon ends and ensuring minimal gapping during healing. It highlights the significance of using multiple suture strands for strength, optimizing suture materials for tensile strength, and different configurations of suture components to minimize gliding friction. Additionally, it compares historical techniques and modern advancements to assess biomechanical strengths and weaknesses for effective tendon repair.