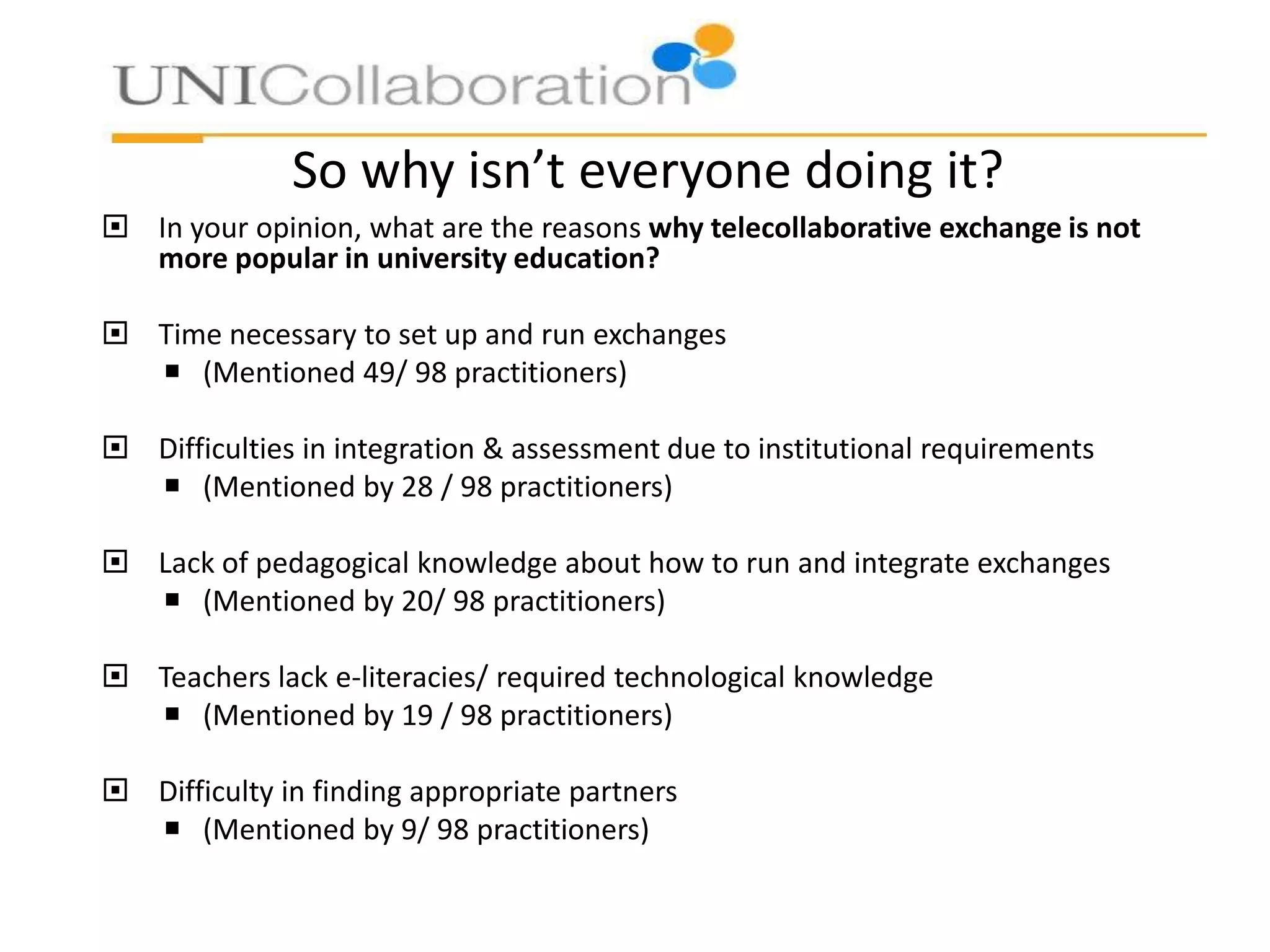

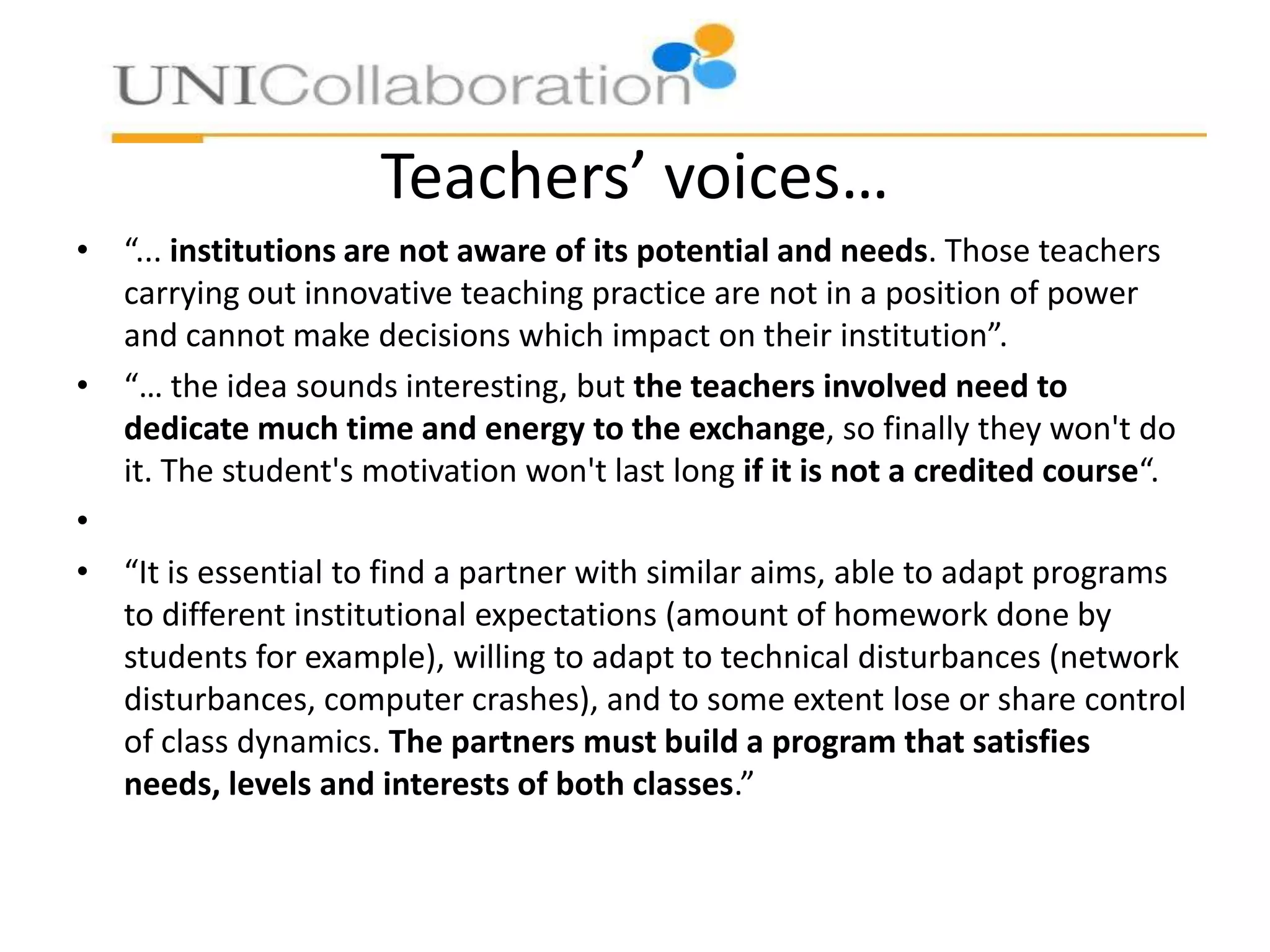

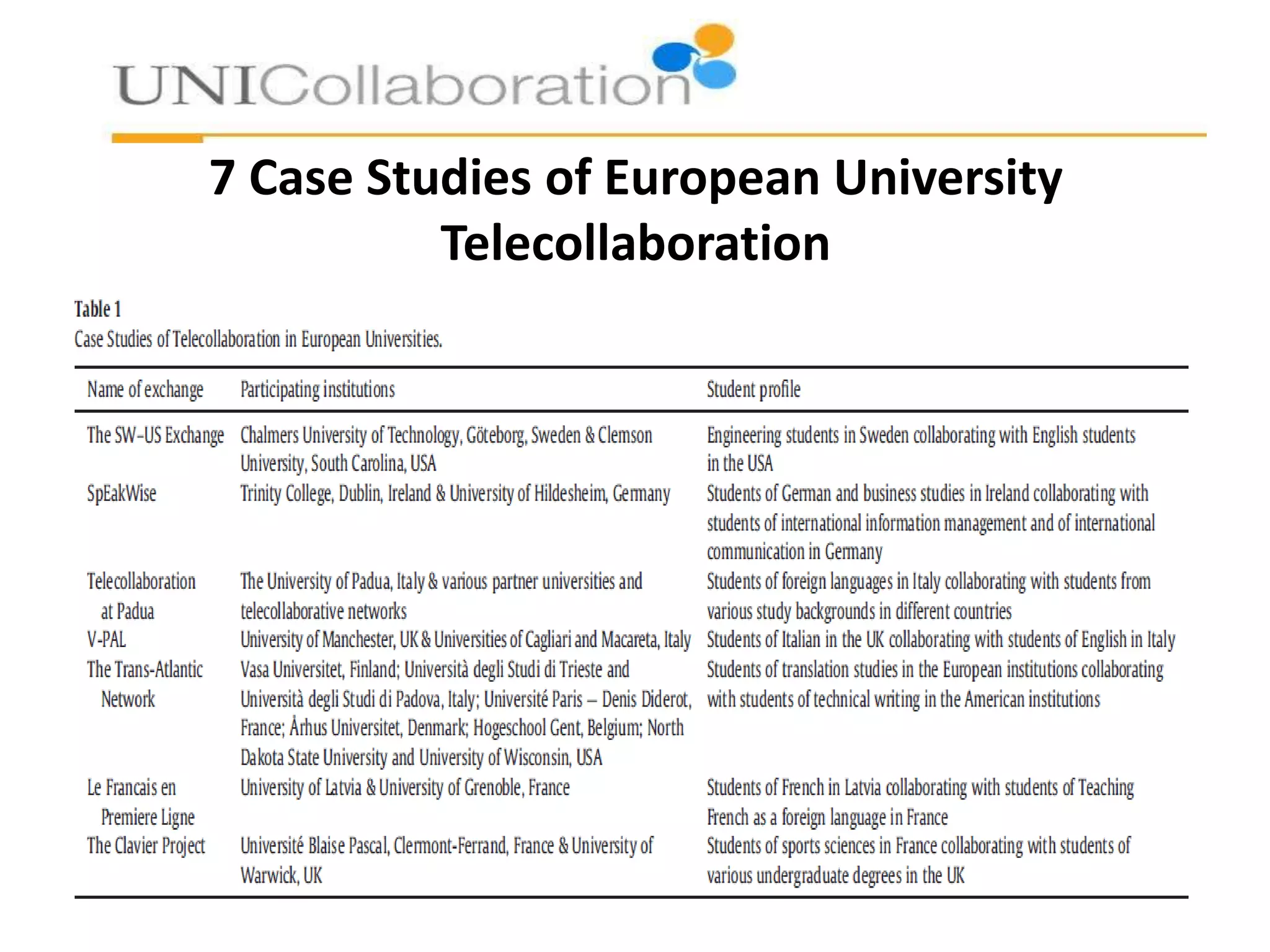

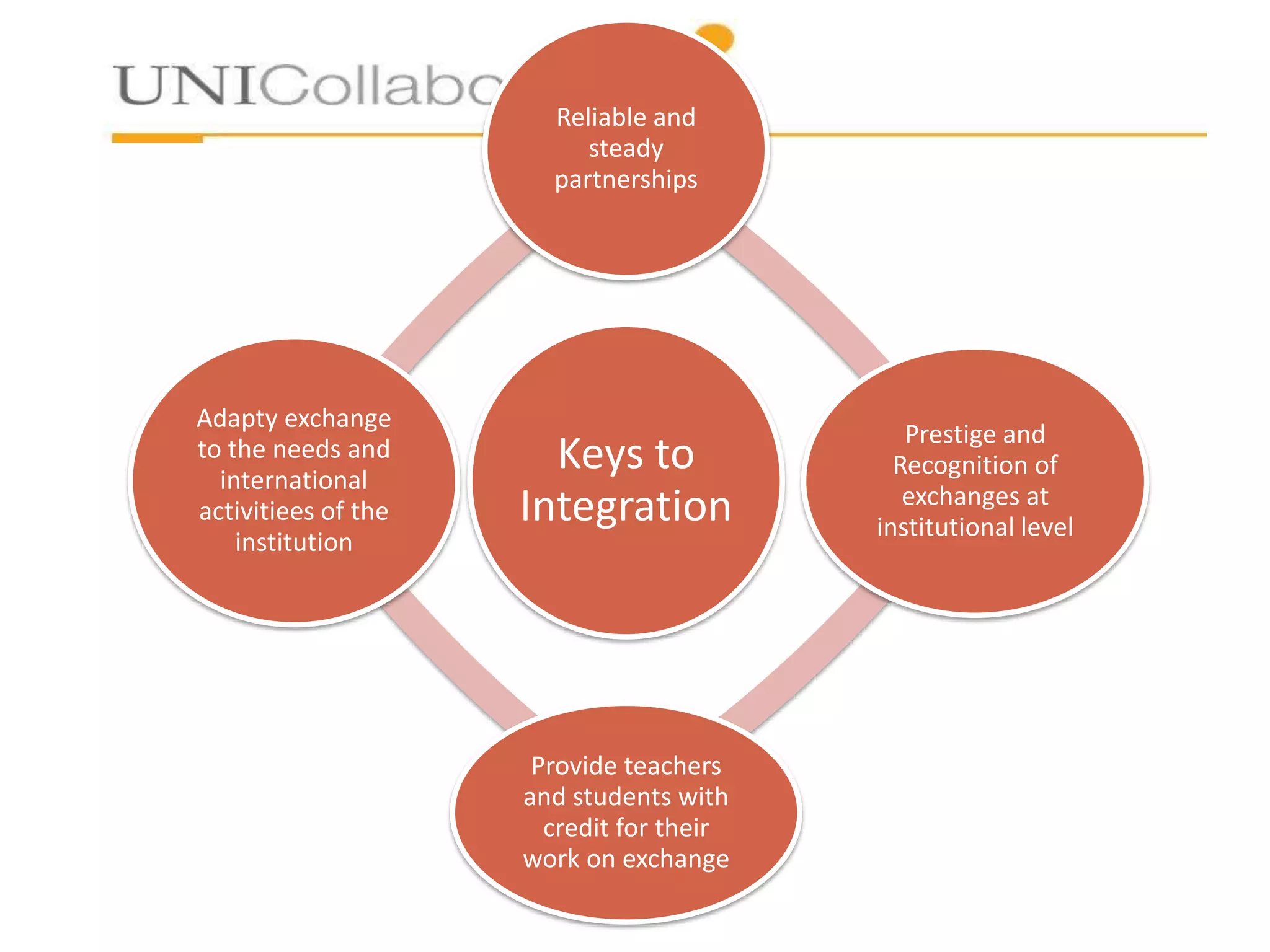

The document discusses keys to integrating telecollaborative exchanges at the institutional level in university education. It identifies five key factors: 1) building reliable and steady partnerships with other institutions, 2) raising awareness and prestige of the exchange within the home institution, 3) adapting the exchange creatively to meet local institutional needs, 4) providing credit or recognition for students' telecollaborative work, and 5) linking the exchange to broader international activities at the institution. The document provides examples from case studies of European universities that have successfully integrated telecollaboration using these five strategies.