This document discusses sustainable economic systems and provides context around stability and sustainability. It covers several key topics:

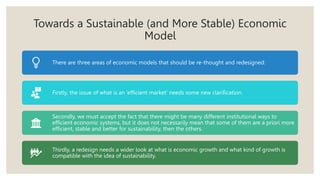

1. It discusses the need for more stability in economic systems to avoid large swings and volatility, as well as the importance of sustainability and responsible use of resources.

2. It analyzes different approaches to economic growth, including "roll-over growth" which can create instability, approaches that focus on continuing growth through technology, and those that advocate for amended growth metrics beyond just GDP.

3. It also discusses the failure of convergence between economic models and the need for pluralism, examining different varieties of capitalism systems and arguments against a one-size-fits-all model.