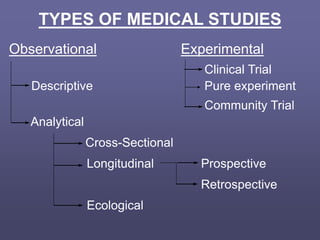

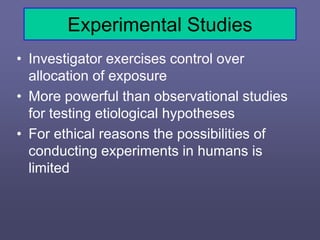

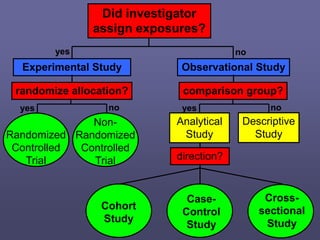

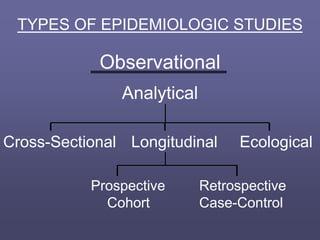

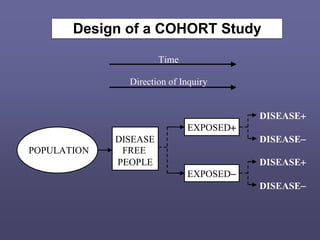

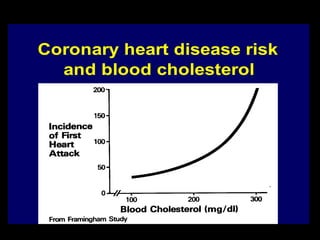

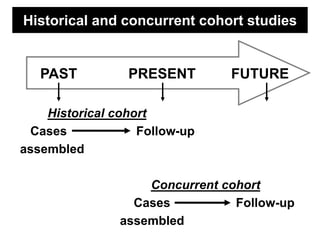

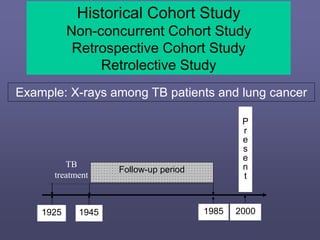

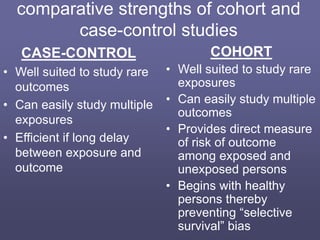

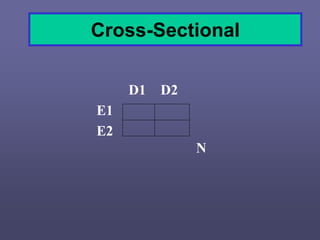

This document describes different types of medical studies, including observational and experimental studies. It provides details on clinical trials, noting that they are the gold standard as they provide the greatest justification for concluding causality. The document outlines different types of observational studies like descriptive, analytical, cross-sectional, longitudinal, retrospective, and prospective studies. It also explains key aspects of experimental studies like clinical/community trials, with details on samples, randomization, interventions, controls, and measuring outcomes.