This document provides an overview and summary of the key features of the 6th edition of the textbook "Sales Management: Analysis and Decision Making."

The textbook continues to use a modular format organized around a sales management model. It blends current sales research with real-world best practices. New features for the 6th edition include opening vignettes for each module, expanded coverage of topics like CRM and outsourcing, and new role-playing exercises. Instructors are supported by an online resource center with materials like PowerPoint slides, test questions, and online student quizzes. The textbook aims to help students develop skills in analyzing sales management situations and making effective decisions.

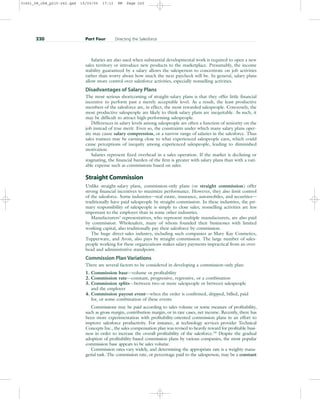

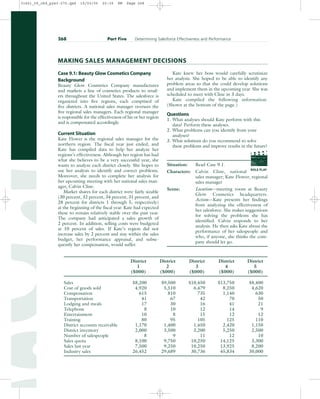

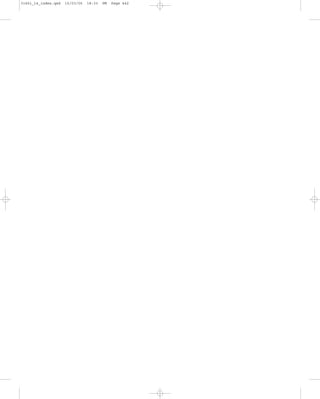

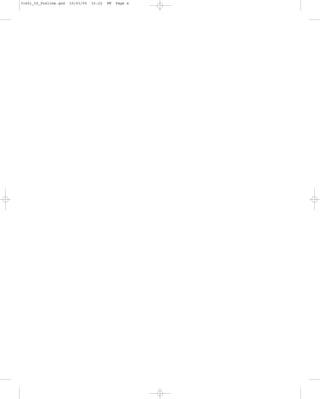

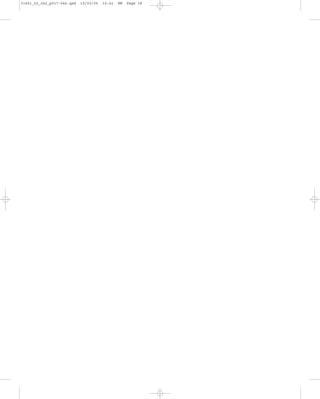

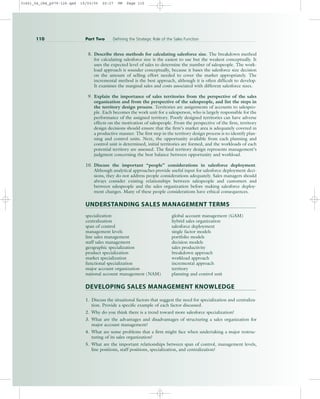

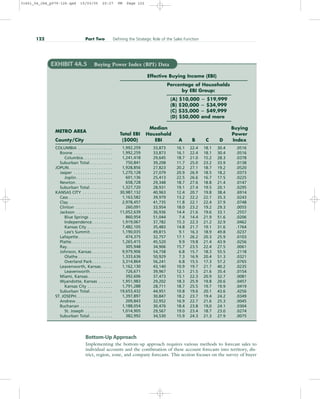

![If the firm added one more salesperson, total profits would be reduced, because

marginal costs would exceed marginal profits by $5,000. Thus, the optimal salesforce

size for this example is 102.

The major advantage of the incremental approach is that it quantifies the important

relationships between salesforce size, sales, and costs, making it possible to assess the

potential sales and profit impacts of different salesforce sizes. It forces management to

view the salesforce size decision as one that affects both the level of sales that can be gen-

erated and the costs associated with producing each sales level.

The incremental method is, however, somewhat difficult to develop. Relatively com-

plex response functions must be formulated to predict sales at different salesforce sizes

(sales f [salesforce size]). Developing these response functions requires either histor-

ical data or management judgment. Thus, the incremental approach cannot be used for

new salesforces where historical data and accurate judgments are not possible.

Turnover

All the analytical tools incorporate various elements of sales and costs in their calcula-

tions. Therefore, they directly address productivity issues but do not directly consider

turnover in the salesforce size calculations. When turnover considerations are important,

management should adjust the recommended salesforce size produced by any of the

analytical methods to reflect expected turnover rates. For example, if an analytical tool

recommended a salesforce size of 100 for a firm that experiences 20 percent annual

turnover, the effective salesforce size should be adjusted to 120. Recruiting, selecting,

and training plans should be based on the 120 salesforce size.

Failure to incorporate anticipated salesforce turnover into salesforce size calculations

can be costly. Evidence suggests that many firms may lose as much as 10 percent in sales

productivity due to the loss in sales from vacant territories or low initial sales when a new

salesperson is assigned to a territory. Thus, the sooner that sales managers can replace

salespeople and get them productive in their territories, the less loss in sales within the

territory.

Outsourcing the Salesforce

The salesforce size decisions we have been discussing apply directly to an ongoing com-

pany salesforce. However, there may be situations where a company needs salespeople

quickly, for short periods of time, for smaller customers, or for other reasons, but does

not want to hire additional salespeople. An attractive option is to outsource the salesforce.

A growing number of companies can provide salespeople to a firm on a contract basis.

These salespeople only represent the firm and customers are typically not aware that these

are contracted salespeople. Contracts can vary as to length, customer assignment, and

other relevant factors. This gives the client firm a great deal of flexibility.

The situation at GE Medical Systems is illustrative. Salespeople at GE Medical

Systems called on hospitals with 100 or more beds in major metropolitan areas. This left

the market for smaller hospitals in rural areas to competitors. GE decided it needed pur-

sue these smaller markets, but did not want to hire additional salespeople or to have

existing salespeople take time away from their large customers. So, GE contracted with

a firm to provide seven salespeople experienced in capital equipment sales to serve the

Module Four Sales Organization Structure and Salesforce Deployment 101

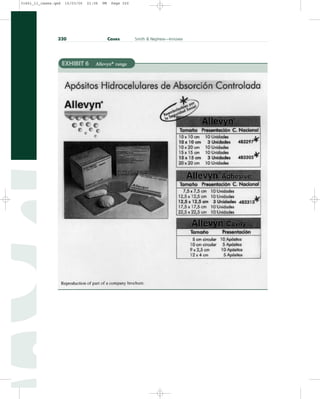

Incremental Approach EXHIBIT 4.4

Number of Marginal Salesperson Marginal

Salespeople Profit Contribution Salesperson Cost

100 $85,000 $75,000

101 $80,000 $75,000

102 $75,000 $75,000

103 $70,000 $75,000

31451_04_ch4_p079-126.qxd 15/03/05 20:26 PM Page 101](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/studentssalesmanagementanalysisanddecisionmaking-220716061409-bf66245b/85/students-Sales-Management-Analysis-and-Decision-Making-pdf-124-320.jpg)

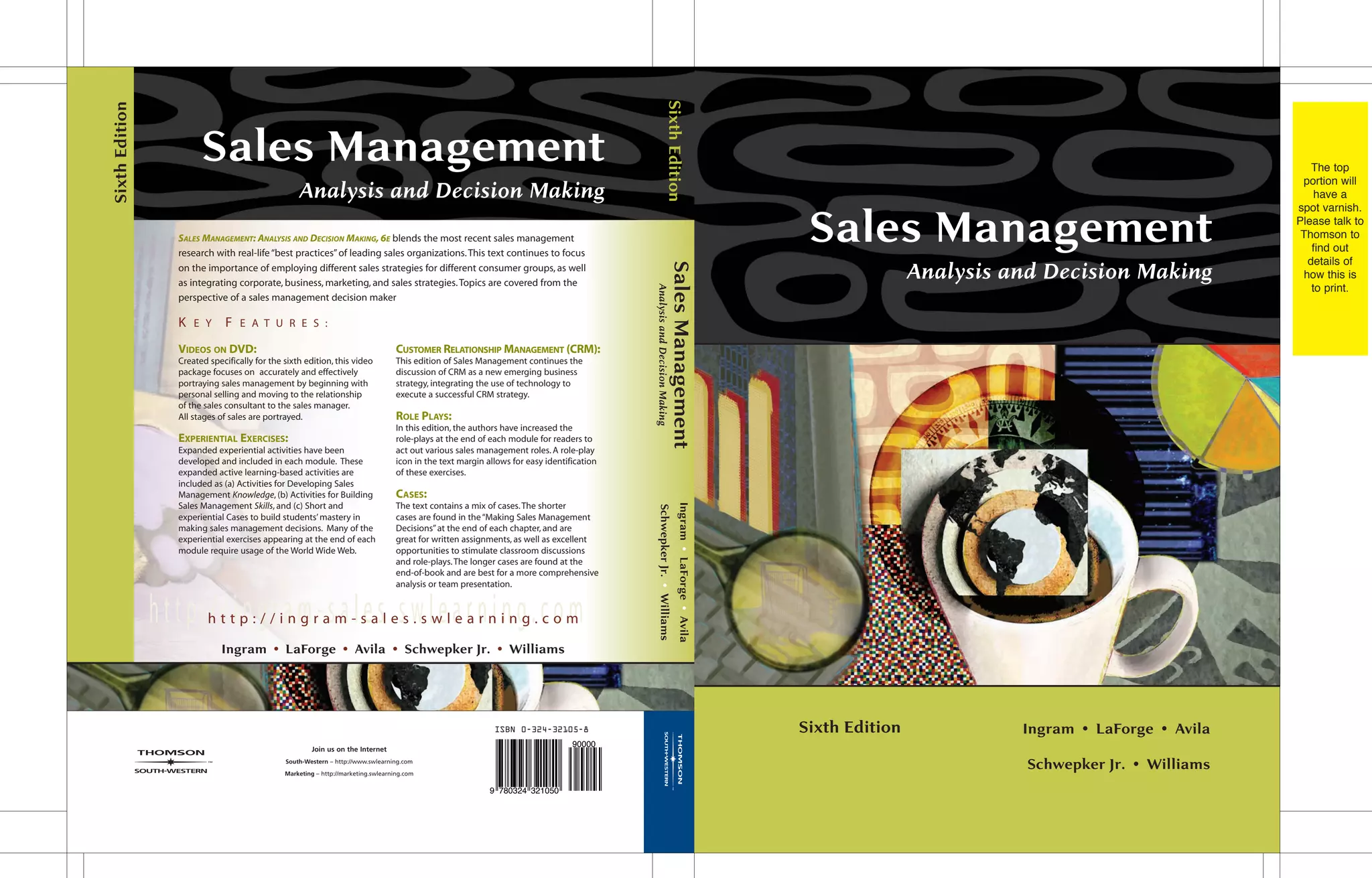

![reason to further customer relationships beyond the third month. The new plan rewards

reps for increasing business in a one-year period and provides them roughly 3 percent

of the total revenue in the account each month after that period. Salespeople have

embraced the new system because they find that it is easier to sell additional products to

a current customer than it is to open a new account.16

The Frontier case illustrates how even the best-run companies can benefit from

better anticipation of problems to avert leadership crises. It is unfair to expect unerr-

ing clairvoyance of sales managers, but it is reasonable to expect that responsible

leaders will try to extend their vision into the future. One way they can do this is to

seek feedback from customers, salespeople, and other important sources regularly.

Feedback can be gathered regularly through field visits, salesforce audits, and con-

scientious reviews of routine call reports submitted by salespeople. The idea of sales

managers spending more time in the field, whether or not they are accompanied by

salespeople, is increasingly being advocated.

One option is for the sales manager to actually spend time in the field in the role of

the salesperson. Some sales managers have actual sales responsibilities; others visit the

field as temporary salespeople. While in the sales role, the manager can assess sales sup-

port, customer service, availability of required information, job stress, workload factors,

and other variables of interest. For example, at Cort Furniture Rental in Capital

Heights, Maryland, sales managers may spend two or more days a month accompany-

ing each salesperson on calls.17

Diagnostic Skills

Effective leaders must be able to determine the specific nature of the problem or oppor-

tunity to be addressed. Although this sounds simple, it is often difficult to distinguish

between the real problem and the more visible symptoms of the problem. Earlier it was

noted that sales managers have relied too heavily on reward and coercive power to direct

their salesforces. A primary reason for this is a recurring tendency to attack easily iden-

tified symptoms of problems, not the core problems that need resolution. Reward and

coercive power are also expedient ways to exercise control, and they suit the manager

who likes to react without deliberation when faced with a problem.

For example, a sales manager may react to sluggish sales volume results by automati-

cally assuming the problem is motivation. What follows from this hasty conclusion is

a heavy dose of newly structured rewards, or just the opposite: a strong shot of coercion.

Perhaps motivation is not the underlying problem; perhaps other determinants of per-

formance are actually the source of the problem. But a lack of diagnostic skills (discussed

194 Part Four Directing the Salesforce

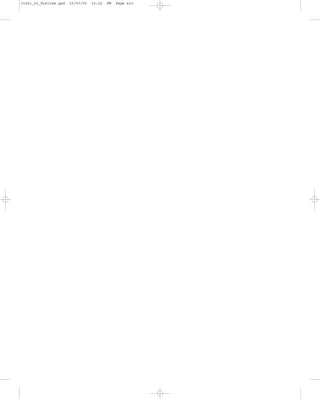

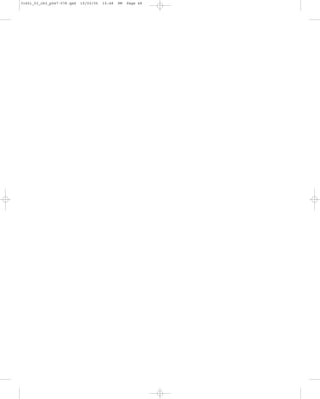

S a l e s m a n a g e m e n t i n t h e 2 1 s t c e n t u r y

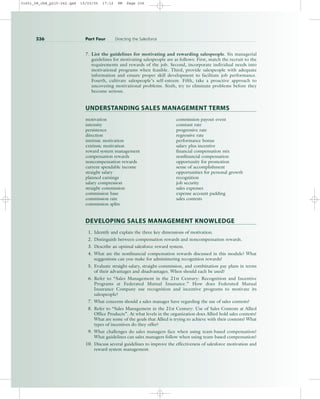

Leading the Salesforce at Federated

Mutual Insurance

Sabrina Rogers, district marketing manager for

Federated Mutual Insurance, discusses her leader-

ship approach.

Leadership in today’s salesforce requires a definite

and positive approach to each team member. My

approach remains consistent. First, Federated has

established a business plan that clearly defines the

[company’s] expectations of each sales representative.

The business plan helps guide each individual to take

responsibility for their own results and, therefore,

contributes to the company’s success. It is my respon-

sibility to ensure that my reps understand the business

plan. Secondly, I strive to provide timely and accu-

rate feedback to each individual regarding the sales

approach and sales techniques. I reinforce positive

behaviors while providing and monitoring alterna-

tives to poor habits. Finally, as a leader, I provide an

example of how to attain goals and overall success

while promoting core values and a good work ethic.

It is imperative that sales representatives understand

that I will work for them and with them.

31451_07_ch7_p185-214.qxd 15/03/05 20:33 PM Page 194](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/studentssalesmanagementanalysisanddecisionmaking-220716061409-bf66245b/85/students-Sales-Management-Analysis-and-Decision-Making-pdf-217-320.jpg)