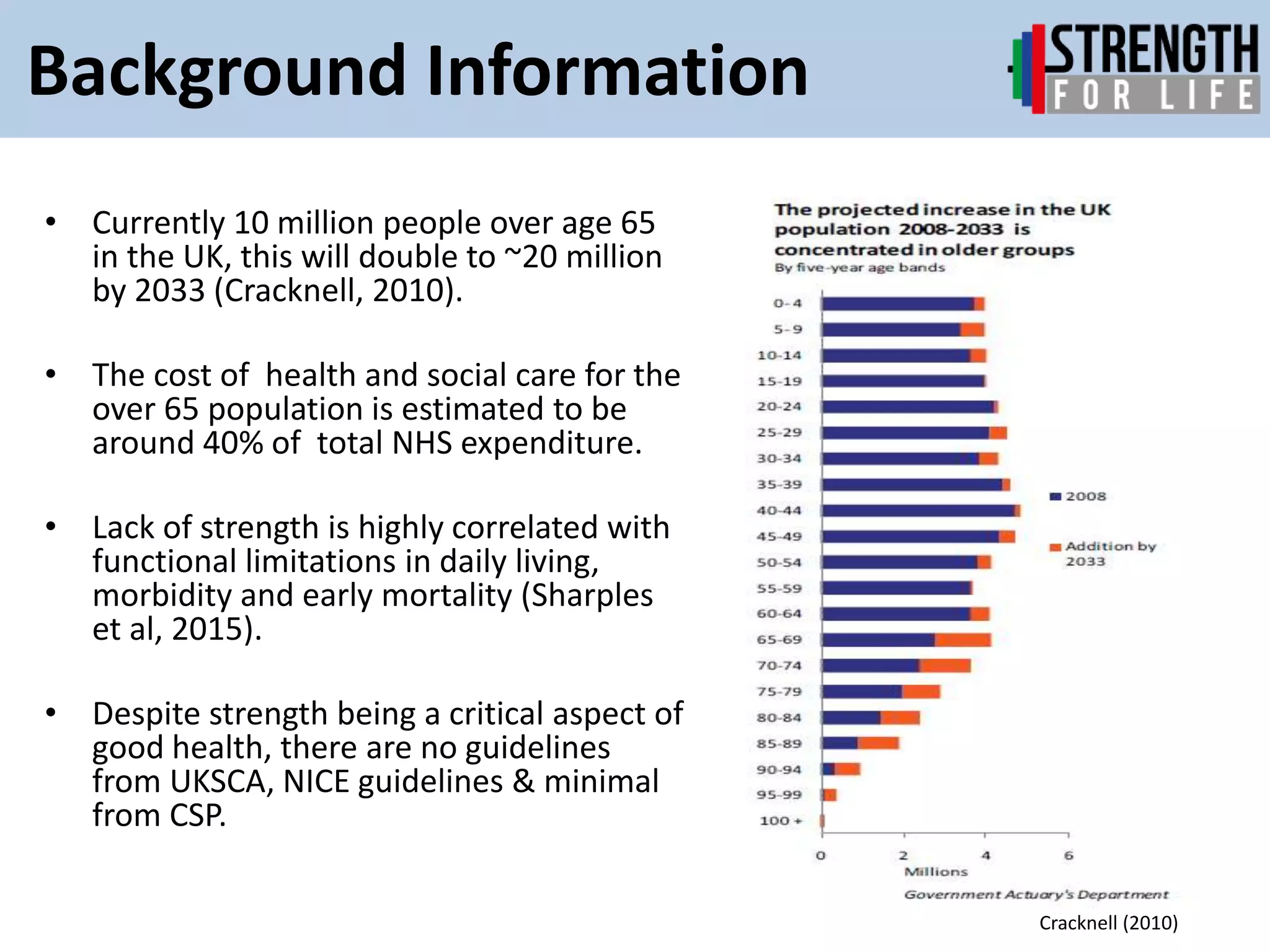

This document provides an overview of strength training for older adults. It discusses the aging population and benefits of strength training for health, physical function, and quality of life. Strength declines significantly with age starting at 45 years old. Inactivity leads to further losses. The document recommends progressive strength training targeting all major muscle groups using varied exercises and resistance. It emphasizes the need for clinical guidelines on strength training for older adults to improve health outcomes and reduce healthcare costs.