This document discusses Parse's evaluation and adoption of the RocksDB storage engine for MongoDB. Some key points:

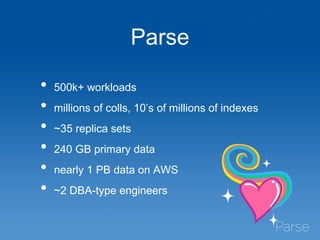

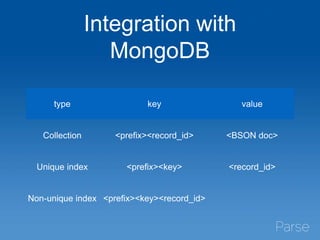

- Parse has a large MongoDB deployment handling millions of collections and indexes across 35 replica sets.

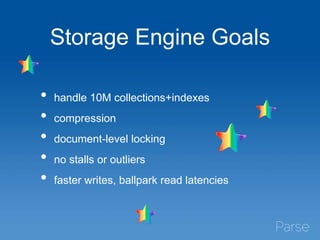

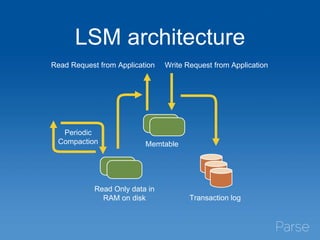

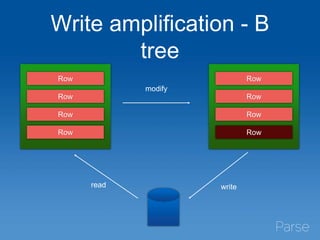

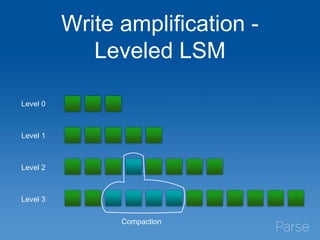

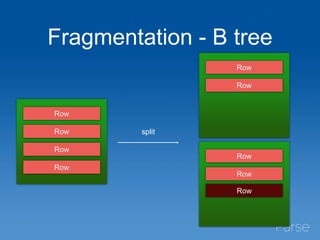

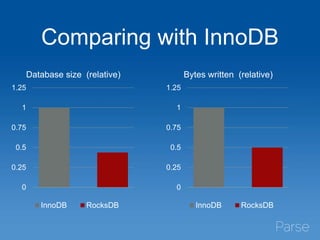

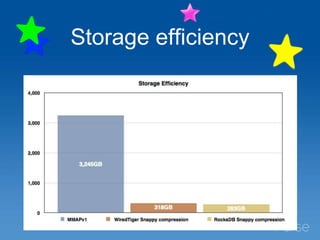

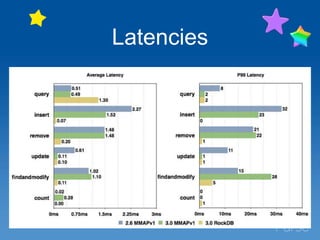

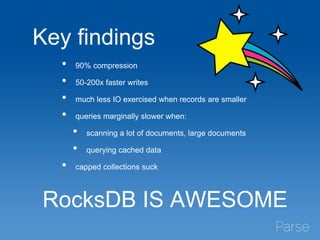

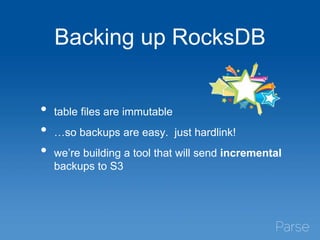

- RocksDB provides higher write throughput, compression, and avoids stalls compared to MongoDB's default storage engines.

- After hidden testing, Parse has deployed RocksDB as the primary storage engine for 25% of replica sets and secondaries for 50% of sets.

- Monitoring and operational tools are being enhanced for RocksDB. Performance continues to improve and wider adoption within the MongoDB community is hoped for.

![Monitoring

db.serverStatus()[‘rocksdb’]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1630ops03-150605215927-lva1-app6892/85/Storage-Engine-Wars-at-Parse-29-320.jpg)

![Monitoring

db.serverStatus()[‘rocksdb’]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1630ops03-150605215927-lva1-app6892/85/Storage-Engine-Wars-at-Parse-30-320.jpg)

![Monitoring

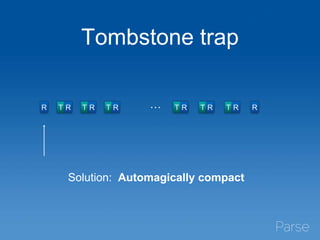

• Tombstones

• Disk I/O saturation

• CPU usage

• Latency

db.serverStatus()[‘rocksdb’]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1630ops03-150605215927-lva1-app6892/85/Storage-Engine-Wars-at-Parse-31-320.jpg)